With Barclay’s defeat, Erie becomes an American lake. Because Perry can cruise these waters with impunity, landing troops anywhere, the British cannot hope to hold the territory captured in 1812. Detroit must be evacuated; Amherstburg, on the Canadian side, is threatened. The British have two choices: to meet the coming invasion at the water’s edge (always supposing they know where it will come), or retire at once to a defensive position up the valley of the Thames, keeping the army intact and stretching the American lines of supply. The British command favours retreat; the Indians want to stay and fight.

Tecumseh is in a violent passion. He has just come over from Bois Blanc Island in the Detroit River, where he and his followers are camped, to find that the fort is being dismantled. What is going on?

It looks very much as if Procter is planning to retreat; but Procter has been remarkably evasive with the Indians. On the day after the naval battle he actually pretended that Barclay had won.

“My fleet has whipped the Americans,” he told the tribesmen, “but the vessels being much injured have gone into Put-in Bay to refit, and will be here in a few days.”

Tecumseh, who is no fool, resents being treated as one. He does not care for Procter. The two have been at loggerheads since Brock’s death, a year ago. Brock, in Tecumseh’s view, was a man; Procter is fit only to wear petticoats. Now the British general fears to face his Shawnee ally with the truth.

Disillusion is gnawing at Tecumseh. Since 1808 he has been the supreme optimist, perfectly convinced that, aided by the compelling new religion of his mystic brother the Prophet, he can somehow weld all the warring and quarrelsome tribes into a mighty confederacy. He is in this war not to help the British but to help his people hold on to their hunting grounds and to their traditional life style. But the war has gone sour, and confederation is not as easy as it once seemed. He cannot convince the southern tribes to join him. And there is more than a suspicion that the young braves who still recognize his leadership are as interested in plunder and ransom money as they are in his grand design.

He is a curious mixture, this muscular Shawnee with the golden skin and hazel eyes who has renounced all pleasures of the flesh to funnel his energies toward a single goal. It is the future that concerns him; but now that future is clouded, and Tecumseh is close to despair. He has already considered withdrawing from the contest, has told his followers, the Shawnee, Wyandot, and Ottawa tribesmen, that the King has broken his promise to them. The British pledged that there would be plenty of white men to fight with the Indians. Where are they?

“The number,” says Tecumseh, “is not now greater than at the commencement of the war; and we are treated by them like the dogs of snipe hunters; we are always sent ahead to start the game; it is better that we should return to our country and let the Americans come on and fight the British.”

Tecumseh’s own people agree. Oddly, it has been Robert Dickson’s followers, the Sioux, and their one-time enemies the Chippewa, who have persuaded him to remain. But Dickson has gone off on one of his endless and often mysterious peregrinations through the wilderness to the west.

Now, with the fort being dismantled, Tecumseh has further evidence of Procter’s distrust. Determined to abandon the British, he goes off in a fury to the home of Matthew Elliott, the Indian Department supervisor at Amherstburg. Ever since the Revolution, Elliott has been friend and crony to the Indians and especially to the Shawnee. At times, indeed, this ageing Irishman seems more Indian than Tecumseh. He fights alongside the Indians, daubed with ochre, has clubbed men to death with a tomahawk and watched others die at the stake – the ritual torture that Tecumseh abhors and prohibits. As events have proved, at both Frenchtown and Fort Meigs, he is less concerned about sparing the lives of prisoners than is Tecumseh. As a result he is, next to Procter, the man whom Harrison’s Kentuckians hate most.

Elliott cringes under Tecumseh’s fury. The Shawnee warns him that if Procter retreats, his followers will in a public ceremony bring out the great wampum belt, symbolic of British-Indian friendship, and cut it in two as an indication of eternal separation. The Prophet himself has decreed it. Worse, the Indians will fall on Procter’s army, which they outnumber three to one, and cut it to pieces. Elliott himself will not escape the tomahawk.

For retreat is not in Tecumseh’s make-up; he believes only in attack. The larger concerns of British strategy in this war are beyond him; his one goal is to kill as many of the enemy as possible. He has been fighting white Americans since the age of fifteen, when he battled the Kentucky volunteers. At sixteen, he was ambushing boats on the Ohio, at twenty-two serving as a raider and scout against the U.S. Army. He was one of the first warriors to break through the American lines at the Wabash during one of the most ignominious routs in American history when, in 1791, Major-General Arthur St. Clair lost half his army to a combined Indian attack. The following year Tecumseh answered the call of his elder brother to fight in the Cherokee war, and when his brother was killed became band leader in his stead, going north again to take part in the disastrous Battle of Fallen Timbers on the Maumee, where Major-General Anthony Wayne’s three thousand men shattered Blue Jacket’s band of fourteen hundred. On that black August day in 1794 Tecumseh, his musket jammed, did his best to rally his followers, waving a useless weapon as they scattered before the American bayonets.

Tecumseh believes in sudden attack: dalliance, even when justified, frustrates him; retreat is unthinkable. When Perry’s fleet first appeared outside Amherstburg he could not understand why Barclay did not go out at once to face it.

“Why do you not go out and meet the Americans?” he taunted Procter. “See yonder, they are waiting for you and daring you to meet them; you must and shall send out your fleet and fight them.”

Since those bloody days on the Wabash and Maumee, facing St. Clair and Wayne, Tecumseh has used another weapon – his golden voice – to frustrate William Henry Harrison’s hunger for Indian lands. Now Harrison, the former governor of Indiana, who did his best to buy up the hunting grounds along the Wabash for a pittance, has Lake Erie to himself. He can land anywhere; and he has a score to settle with Tecumseh, who frustrated his land grab. Tecumseh, too, has a score to settle with Harrison, who destroyed the capital of his confederacy on the Tippecanoe. He cannot wait to get at the General; and he will use the weapon of his oratory to rally his people and blackmail the British into standing fast.

The following morning, he summons his followers from Bois Blanc Island. They squat in their hundreds on the fort’s parade ground as Tecumseh strides over to a large stone on the river bank. It is here that announcements of importance are made and here that Tecumseh, the greatest of the native orators – some say the greatest orator of his day – makes the last speech of his life.

It is to Procter, standing nearby with a group of his officers, that Tecumseh, speaking through an interpreter, addresses his words.

First, his suspicions, born of long experience, going back to the peace that followed the Revolution:

“In that war our father was thrown on his back by the Americans. He then took the Americans by the hand without our knowledge, and we are afraid that our father will do so again.…”

Then, after a reference to British promises to feed the Indian families while the braves fought, a brief apology for the failure at Fort Meigs: “It is hard to fight people who live like ground hogs.”

Then:

“Father, listen. Our fleet has gone out, we know they have fought. We have heard the great guns, but know nothing of what has happened to our father with one arm. Our ships have gone one way and we are much astonished to see our father tying up everything and preparing to run the other, without letting his red children know what his intentions are. You always told us to remain here and take care of our land.… You always told us you would never draw your foot off British ground. But now, Father, we see that you are drawing back, and we are sorry to see our father doing so without seeing the enemy. We must compare our father’s conduct to a fat animal that carries its tail upon its back. But when affrighted, it drops it between its legs and runs off.…”

Tecumseh urges Procter to stay and fight any attempt at invasion. If he is defeated, he himself will remain on the British side and retreat with the troops. If Procter will not fight, then the Indians will:

“Father, you have got the arms and ammunition.… If you have any idea of going away, give them to us.… Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit; we are determined to defend our land; and if it is his will, we wish to leave our bones upon it.”

As always, Tecumseh’s eloquence has its effect. Some of his people leap up, prepared to attack the British immediately if their leader gives the word. But Tecumseh is placated when Procter promises to hold a council with the tribesmen on September 18.

Procter faces serious problems. The fort is defenceless, having been stripped of its cannon to arm the new ship, Detroit. One-third of his troops have been lost to him as a result of Perry’s victory. He is out of provisions and must call on Major-General Vincent’s Centre Division to send him supplies overland, since the water route is now denied him by the victorious Americans. Harrison not only has a formidable attack force but he also has the means to convey it, unchallenged, to Canada. Procter’s own men are battle weary, half famished, and despondent over the loss of the fleet.

He does not have the charisma to rally his followers – none of Brock’s easy way with men, or Harrison’s. He is in his fiftieth year, a competent enough soldier, unprepossessing in features, and not very imaginative. There is a heaviness about him; his face is fleshy, his body tends to the obese – “one of the meanest looking men I ever saw,” in the not unbiased description of an American colonel, William Stanley Hatch. When Brock remarked that the 41st was “badly officered” he undoubtedly meant men like Procter; yet he also must have thought Procter the best of the lot, for he put him in command at Amherstburg and confirmed him as his deputy after the capture of Detroit.

Procter suffers from three deficiencies: he is indecisive, he is secretive, and he tends to panic. When Brock wanted to cross the Detroit River and capture William Hull’s stronghold in a single bold, incisive thrust, Procter was against it. When Procter’s own army crept up on the sleeping Kentuckians at the River Raisin, Procter hesitated again, preferred to follow the book, wasted precious minutes bringing up his six-pounders instead of charging the palisade at once and taking the enemy by surprise. When he was finally convinced of the fleet’s loss on September 13, he held a secret meeting with his engineering officer, his storekeeper, and his chief gunner, ordered the dismantling of the fort and the dispatching of stores and artillery to the mouth of the Thames. But he did not tell his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel Augustus Warburton, who is understandably piqued at being left in the dark. When Warburton protests, Procter curtly tells him he has a perfect right to give secret orders. A right, certainly; but it is an axiom of war that subordinates should be kept informed.

There are good reasons for Procter to withdraw from Fort Amherstburg. Harrison has total mobility. Perry’s fleet can now land his troops anywhere along Erie’s north shore to outflank the British and take them from the rear. But if Procter moves up the Thames Valley he can stretch Harrison’s line of supply and buy time to prepare a strong defensive position. The bulk of the American force is made up of militia men who have signed up for six months. If past experience means anything, Harrison will have difficulty keeping them after their term is up, especially with the Canadian winter coming on.

He must move quickly if he is to move at all; otherwise Harrison will be at his heels, giving him no chance to prepare a defence on ground of his own choosing. And here Procter stumbles. Inexplicably, he has been told by his superiors not to retire speedily. “Retrograde movements … are never to be hurried or accelerated,” Prevost’s aide writes from Kingston. And De Rottenburg, at Four Mile Creek on Lake Ontario, believes that the enemy’s ships are in no condition to move after the battle – therefore Procter should take time to conciliate the Indians.

Procter, by his secrecy, has already wasted time. Almost a week passes before the promised meeting with the tribesmen. Even if they agree to move with the British, the logistics will be staggering. With women and children, their numbers exceed ten thousand. All must be brought across from Bois Blanc Island and from Detroit (which the British will have to evacuate) and moved up the Thames Valley. The women and children will go ahead of the army along with those white settlers who do not wish to remain under foreign rule. The sick must be removed as well – an awkward business – together with all the military stores. It is a mammoth undertaking, requiring drive, organizational ability, decision, and a sense of urgency. Procter does not display any of these qualities. And when he hears from De Rottenburg, he is given plenty of excuse to drag his feet.

He meets the Indians on September 18. Tecumseh urges that Harrison be allowed to land and march on Amherstburg. He and his Indians will attack on the flank with the British facing the front. If the attack fails, Tecumseh says, he can make a stand at the River aux Canards, which he defended successfully the previous year. When Procter rejects this plan, Tecumseh, in a fury, calls him “a miserable old squaw.” At these words, the chiefs leap up, brandishing tomahawks, their yells echoing down from the vaulted roof of the lofty council chamber.

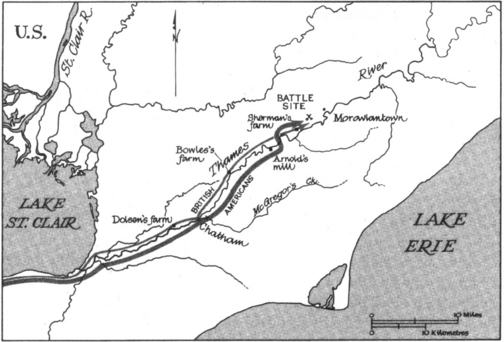

The time for secrecy is past. Procter unrolls a map and explains his position to the Shawnee war chief. If the gunboats come up the Detroit River, he points out, they can cut off the Indians camped on the American side of the river, making it impossible for them to support the British. Harrison can then move on to Lake St. Clair and to the mouth of the Thames, placing his men in the British rear and cutting off all retreat. Tecumseh considers this carefully, asks many questions, makes some shrewd remarks. He has never seen a map like this before. The country is new to him, but he quickly grasps its significance.

Procter offers to make a stand at the community of Chatham, where the Thames forks. He promises he will fortify the position and will “mix our bones with [your] bones.” Tecumseh asks for time to confer with his fellow chiefs. It is a mark of his flexibility that he is able to change his mind and of his persuasive powers that after two hours he manages to convince the others to reverse their own stand and follow him up a strange river into a foreign country.

Yet Tecumseh still has doubts. On September 23, after destroying Fort Amherstburg, burning the dockyard and all the public buildings, the army leaves for Sandwich. Tecumseh views the retreat morosely.

“We are going to follow the British,” he tells one of his people, “and I feel that I shall never return.”

The withdrawal is snail-like. It has taken ten days to remove all the stores and baggage by wagon and scow. The townspeople insist on bringing their personal belongings, and this unnecessary burden ties up the boats, causing a delay in transporting the women, children, and sick. Matthew Elliott, for example, takes nine wagons and thirty horses to carry the most valuable part of his belongings, including silver plate worth fifteen hundred pounds. The organization of the military stores is chaotic. Entrenching tools, which ought to be carried with the troops, are shifted to the bottoms of the boats after the craft are unloaded to take them across the bar at the mouth of the Thames. The rest of the cargo is piled on top, making them difficult to reach.

On the twenty-seventh, more than a fortnight after Barclay’s defeat, Major Adam Muir destroys the barracks and public buildings at Detroit and moves his rearguard across the river. All of the territory captured by Brock in 1812 – most of Michigan – is now back in American hands. At five the same day, Lieutenant-Colonel Warburton marches his troops out of Sandwich.

That same evening, Jacques Baby, a member of a prominent merchant and fur-trading family and a lieutenant-colonel in the militia, gives a dinner for the senior officers of the 41st in his stone mansion in Sandwich. Tecumseh attends wearing deerskin trousers, a calico shirt, and a red cloak. He is in a black mood, eats with his pistols on each side of his plate, his hunting knife in front of it.

Comes a knock on the door – a British sergeant announcing that the enemy fleet has entered the river and is sailing northward near Amherstburg. Tecumseh, whose English is imperfect, fails to catch the import of the message and asks the interpreter to explain. Then he rises, hands on pistols, and turns to General Procter.

“Father, we must go to meet the enemy.… We must not retreat.… If you take us from this post you will lead us far, far away … tell us Good-bye forever and leave us to the mercy of the Long Knives. I tell you I am sorry I have listened to you thus far, for if we remained at the town … we could have kept the enemy from landing and have held our hunting grounds for our children.

“Now they tell me you want to withdraw to the river Thames.… I am tired of it all. Every word you say evaporates like the smoke from our pipes. Father, you are like the crawfish that does not know how to walk straight ahead.”

There is no reply. The dinner breaks up as the guests join the withdrawing army. Tecumseh has no choice but to follow the British with those warriors still loyal to his cause. By now these number no more than one thousand. The Ottawa and Chippewa bands have already sent three warriors to make peace terms with Harrison. The Wyandot, Miami, and some Delaware are about to follow suit.

In the days that follow, Henry Procter, obsessed by the problems of the Indians, abandons any semblance of decisive command. In 1812 the tribesmen were essential to victory; without them Upper Canada might well have become an American fief. Now they have become an encumbrance. Procter literally fails to burn his bridges behind him – an act that would certainly delay Harrison – because he believes that if he does so the Indians, who follow the troops, will think themselves cut off and abandon the British cause. To Lieutenant-Colonel Warburton’s disgust, he purposely holds back the army in order to wait for the Indians. He does not, however, give that reason to his second-in-command but merely says that the troops should rest in their cantonments because of wet weather.

Retreat Up the Thames, September 27-October 5, 1813

Indeed, he tells Warburton very little. Nor does he stay with the army. Mindful of his pledge to Tecumseh to make a stand at the forks of the Thames, he dashes forward on a personal reconnaissance, leaving Warburton without instructions – an action his officers find extraordinary.

He cannot get the Indians out of his mind. Their presence haunts him; the promises wrung from him at the council obsess him; Tecumseh’s taunts clearly sting. And there is something more: his own superiors have harped again and again on the necessity of placating the tribesmen. De Rottenburg has expressly told him that he must “prove to them the sincerity of the British Government in its intent not to abandon them so long as they are true to their own interests” (which, translated, means as long as the Indians are prepared to fight for the British). Prevost has ordered him to conciliate the Indians “by any means in your power” – promising them mountains of presents if they will only follow the army. It is clear that the high command, taking its cue from the evidence of 1812, believes the Indians hold the key to victory; it does not occur to any that they may be the impediment that leads to defeat. There is also in the minds of Procter and his superiors another fear: if the Indians defect, may they not fall upon the British, destroy the army, and then swell the ranks of the invaders? Procter is caught in a trap: if he loses his native allies the blame will fall on him, but as long as Tecumseh is his ally, Procter is not his own man.

He sends his engineering officer, Captain Matthew Dixon, upstream to the forks of the Thames at the community of Chatham. Dixon’s report is negative: it is not the best place to make a stand. But something must be done, the General says; he has promised Tecumseh. Dixon is badgered into agreeing that the tiny community of Dover, three miles downstream from Chatham, is a slightly better position, but he cannot really recommend it. Procter seizes on this, appoints an assistant engineer, Crowther, to fortify the spot, ordering him to dig entrenchments and to place light guns at two or three points.

His heart is not in it. He and Dixon take off immediately for Moraviantown, twenty-six miles upstream, a much better position already recommended by the eccentric militia colonel and land developer, Thomas Talbot. In his haste, Procter does not think to inform his second-in-command, Warburton, marching up the valley with the army.

The General’s intentions are clear: the army will stand and fight at Moraviantown, not at the forks. But Henry Procter will always be able to say he kept his promise to Tecumseh.

As the British fire the public buildings in Detroit and move back into Canada, twelve hundred mounted Kentucky riflemen, led by the fiery congressman, Colonel Richard Johnson, gallop along the Detroit road to reinforce Harrison’s invasion army. Here they pause at the site of their state’s most humiliating defeat to find the bones of their countrymen still unburied and strewn for three miles over the golden wheatfields and among the apple orchards.

The grisly spectacle rekindles the volunteers’ thirst for revenge. Here, on a bitterly cold day the previous January, Procter’s Indians struck down the flower of Kentucky, massacring them without quarter, butchering the wounded, burning some alive after putting the torch to buildings, holding others for ransom. Remember the Raisin! is the only recruiting cry needed in the old frontier commonwealth. Kentucky now has more men under arms than any state in the Union.

The regiment halts to bury the dead. Captain Robert McAfee writes in his diary that “the bones … cry aloud for revenge.… The chimneys of the houses where the Indians burnt our wounded prisoners … yet lie open to the call of vindictive Justice.…” The scene is rendered more macabre that night by a tremendous lightning storm “as if the Prince of the Power of the air … was invited at our approach to scenes of Bloodshed.…”

Its task completed, the regiment rides on toward Detroit, where William Henry Harrison awaits them. Most have been in the saddle since mid-May, after Harrison had asked for reinforcements to relieve Fort Meigs. Richard Johnson was only too eager to answer the call. Without waiting for War Department approval, he issued a proclamation:

Fort Meigs is attacked – the North Western army is Surrounded … nobly defending the Sacred Cause of the Country.… The frontiers may be deluged with blood; the Mounted Regiment will present a Shield to the defenseless.…

Every arrangement shall be made – there shall be no delay. The soldier’s wealth is HONOR – connected with his Country’s cause, is its Liberty, independence and glory, without exertions Rezin’s [sic] bloody scene may be acted over again and to permit [this] would stain the national character.…

Such purple sentiments spring easily from Richard Mentor Johnson’s pen. At thirty-two a handsome, stocky figure with a shock of auburn hair, he has made a name for himself as an eloquent, if florid, politician. The first native-born Kentuckian to be elected to both the state legislature and the federal congress, he is a crony of Henry Clay and a leading member of the group of War Hawks who goaded the country into war. Like so many of his colleagues, he is a frontiersman by temperament, reared on tales of Indian depredations. His family were Indian fighters by inclination as well as of necessity. He has heard from his mother the story of one siege, when, as she was running from the blockhouse for water, a lighted arrow fell on her son’s cradle. Fortunately for Richard Johnson it was snuffed out.

Unlike the aloof New Englanders or the hesitant Pennsylvanians, Kentuckians regard the invasion of Canada as a holy war, “a second revolution as important as the first,” in Johnson’s belief. It is also seen as a war of conquest: Johnson makes no bones about that. England must be driven from the New World: “I shall never die contented until I see … her territories incorporated with the United States.”

The “men of talents, property and public spirit” who flock to Johnson’s banner in unprecedented numbers – old Revolutionary soldiers, ex-Indian fighters, younger bloods raised on tales of derring-do – agree. All have made their wills, have resolved never to return to their state unless they come back as conquerors “over the butcherly murderers of their countrymen.” Robert McAfee, first captain of the first battalion, is typical. On reaching the shores of Lake Erie he foresees in his imagination huge cities and an immense trade-the richest and most important section of the Union. “It is necessary that Canada should be ours,” he writes in his journal.

Johnson and his brother, James, have fifteen hundred six-month volunteers under their command, each decked out in a blue hunting shirt with a red belt and blue pantaloons, also fringed with red. They are armed with pistols, swords, hunting knives, tomahawks, muskets, and Kentucky squirrel rifles. Their peregrinations since mid-May have been both exhausting and frustrating, for they have been herded this way and that through the wilderness for more than twelve hundred miles without once firing a shot at the enemy.

At last the action they crave seems imminent. Johnson can hardly wait to get at the “monster,” Procter. His men are no less eager as they ride toward Detroit, swimming their horses across the tributary streams, on the lookout for hostile Indians, elated by news of the British withdrawal. On the afternoon of the thirtieth they reach their objective. The entire population turns out to greet them, headed by the Governor of Kentucky himself, old Isaac Shelby, who at Harrison’s request has brought some two thousand eager militiamen to swell the ranks of the invading army.

The tide is turning for the Americans. Johnson learns that Harrison has already occupied Amherstburg, surprised that Procter abandoned it without offering resistance. Harrison now has a force of five thousand men, including two thousand regulars. He does not expect to catch Procter because the British have commandeered every horse in the country. It is all he can do to find a broken-down pony to carry the ageing Shelby.

Harrison has one hope: that Procter will make a stand somewhere on the Thames. His “greatest apprehensions,” as he tells the Secretary of War, “arise from the belief that he will make no halt.” In that case, perhaps he ought to move his army up the north shore of Lake Erie aboard the fleet, and attack the British rear.

At dawn on the morning of September 30 he and Shelby meet in a small private room in his headquarters at Amherstburg to discuss tactics. The Governor is here at Harrison’s personal request, technically in command of all Kentucky militia.

“Why not, my dear sir, come in person?” Harrison asked him in a flattering letter. “You would not object to a command that would be nominal only. I have such confidence in your wisdom that you in fact should be ‘the guiding head and I the hand.’ ”

Harrison – a scholarly contrast to the ragtag crew of near illiterates who officer the militia – cannot resist a classical allusion:

“The situation you would be placed in is not without its parallel. Scipio, the conqueror of Carthage, did not disdain to act as a lieutenant of his younger and less experienced brother, Lucius.”

It is a shrewd move. Shelby, an old frontiersman and Revolutionary warrior, cannot resist Harrison’s honeyed pleas. He is sixty-three, paunchy and double-chinned, with close-cropped white hair. But he commands the respect of Kentuckians, who call him “Old King’s Mountain” after his memorable victory at that place in 1780 and flock to his command in double the numbers required.

Harrison wants the Governor’s opinion: the army can pursue Procter by land up the Thames Valley or it can be carried by water to Long Point, along the lake, and march inland by the Long Point road to intercept the British.

Shelby replies that he believes Procter can be overtaken by land. With that the General calls a council of war to confirm the strategy. It opts for a land pursuit.

Harrison decides to take thirty-five hundred men with him, leaving seven hundred to garrison Detroit. Johnson’s mounted volunteers, brought over early next morning, will lead the van. The remainder of the force, whose knapsacks and blankets have been left on an island in the river, will follow.

The General has the greatest difficulty persuading any Kentuckian to stay on the American side of the Detroit River. All consider it an insult to be left behind; in the end, Harrison has to resort to a draft to keep them in Detroit. The Pennsylvania militia, on the other hand, stand on their constitutional right not to fight outside the territorial limits of the United States.

“I believe the boys are not willing to go, General,” one of their captains tells him.

“The boys, eh?” Harrison remarks sardonically. “I believe some of the officers, too, are not willing to go. Thank God I have Kentuckians enough to go without you.”

Speed is of the essence. As Shelby keeps saying: “If we desire to overtake the enemy, we must do more than he does, by early and forced marches.”

And so, at first light on October 2, as Procter dawdles, the Americans push forward, sometimes at a half run to keep up with the mounted men. Johnson asks Harrison’s permission to ride ahead in search of the British rearguard. Harrison agrees but, remembering the disaster before Fort Meigs, adds a word of caution.

“Go, Colonel, but remember discipline. The rashness of your brave Kentuckians has heretofore destroyed themselves. Be cautious, sir, as well as brave and active, as I know you all are.”

Johnson rides off with a group of volunteers. Not far from the Thames, they capture six British soldiers and learn that Procter’s army is only fifteen miles above the mouth of the Thames. It is now nearly sunset, but when the regiment hears this, it determines to move on to Lake St. Clair. In one day Harrison’s army has marched twenty-five miles.

The troops set off again at dawn. Since only the three gunboats with the shallowest draft can ascend the winding Thames, Oliver Hazard Perry, who is eager to see action, signs on as Harrison’s aide. Harrison concludes that Procter is unaware of his swift approach, for he has not bothered to destroy any bridges to slow the American advance. Then, at the mouth of the Thames, an eagle is spotted hovering in the sky. Harrison sees it as a victory omen, especially after Perry tells him his seamen had noticed a similar omen the morning of the lake battle. The Indians, it seems, are not the only warriors who believe in signs and portents.

That afternoon, the army captures a British lieutenant and eleven dragoons. From these prisoners Harrison learns that the British have as yet no certain information of his advance.

By evening, the army is camped ten miles up the river, just four miles below Matthew Dolsen’s farm at Dover, from which the British have only just departed. It has taken Procter’s army five days to make the journey from Sandwich. Harrison has managed to cover the same ground in less than half the time.

Augustus Warburton is a confused and perplexed officer. Procter’s second-in-command has no idea what he is to do because his commander has not told him. Word has reached him that the Americans are on the march a few miles downstream. His own men have reached the place where Procter decided to make a stand, but Procter has rushed up the river to Moraviantown, having apparently decided to meet the enemy there.

Now Captain William Crowther comes to Warburton with a problem. Procter has ordered him to fortify Dover; he wants to throw up a temporary battery, cut loopholes in the log buildings, dig trenches. But all the tools have been sent on to Bowles’s farm seven miles upriver, and there are neither wagons nor boats to bring them back. Crowther is stymied.

It is too late, anyway, for Tecumseh, on the opposite bank, insists on moving three miles upstream to Chatham, at the forks. It was there that Procter originally promised to make a stand and, if necessary, lay his bones with those of the Indians. Tecumseh has not been told of any change of plans.

Nor has Warburton. His officers agree that the Indians must be conciliated. As a result, the army, which has lingered at Dolsen’s for two days, moves three miles to Chatham and halts again. Tecumseh – not Procter, not Warburton – is calling the tune.

Tecumseh is in a fury. There are no fortifications at Chatham; Procter has betrayed him! Half his force leaves, headed by Walk-in-the-Water of the senior tribe of Wyandot. Matthew Elliott’s life is threatened.

Elliott crosses the river and, in a panic, urges Warburton to stand and fight at Chatham.

“I will not, by God, sacrifice myself,” he cries, in tears.

He is a ruined man, Elliott, in every sense, and knows it. Financially, he is approaching destitution. His handsome home at Amherstburg has been gutted by the Kentuckians – the furniture broken, fences, barns, storehouses destroyed. His personal possessions are in immediate danger of capture. And his power is gone: the Indians no longer trust him. Once he was the indispensable man, his influence over the American tribes so great that the British restored him to duty after a financial scandal that would have destroyed a lesser official. Now all that has ended. The frontier days are over. The Old Northwest, which Elliott and his cronies, Simon Girty and Alexander McKee, knew when they fought beside the braves against Harmar, St. Clair, and Wayne, is no more. Except for Tecumseh’s dwindling band, the native warriors have been tamed. The old hunting grounds north of the Ohio are already threatened by the onrush of white civilization. Here on the high banks of the Thames, the faltering Indian confederacy will stand or fall.

Warburton asks Elliott to tell Tecumseh that he will try to comply with Procter’s promises and make a stand on any ground of the Indian’s choosing. He has already sent two messages to Procter, warning him that the enemy is closing in and explaining that he has moved forward to Chatham. But Procter goes on to Moraviantown regardless and, after sending his wife and family off to safety at Burlington Heights, remains there for the night.

The Indians are angered at Procter’s inexplicable absence. Tecumseh’s brother, the Prophet, says he would like personally to tear off the General’s epaulettes; he is not fit to wear them. The army, too, is disturbed. Mutiny is in the air. There is talk of supplanting Procter with Warburton, but Warburton will have none of it, a decision that causes Major Adam Muir of the rearguard to remark that Procter ought to be hanged for being absent and Warburton hanged with him for refusing responsibility.

Early on the morning of October 4 (the Americans have been camped all night at Dolsen’s), Warburton gets two messages. The first, from Procter, announces that he will leave Moraviantown that day to join the troops. The second, from Tecumseh, tells him that the Indians have decided to retire to the Moravian village.

Warburton waits until ten; no Procter. Across the river he can hear shots: the Indians are skirmishing with the enemy. Just as he sets his troops in motion another message arrives from Procter, ordering him to move a few miles upriver to Bowles’s farm. The column moves slowly, impeded by the Indian women who force it to halt time after time to let them pass. At Bowles’s – the head of navigation on the river – Warburton encounters his general giving orders to destroy all the stores collected there – guns, shells, cord, cable, naval equipment. In short, the long shuttle by boat from Amherstburg, which delayed the withdrawal, has been for nothing. Two gunboats are to be scuttled in the river to hinder the American progress.

At eight that evening the forward troops reach Lemuel Sherman’s farm, some four miles from Moraviantown, and halt for the night. Here, ovens have been constructed and orders given for bread to be baked; but there is no bread, the bakers claiming that they must look first to their families and friends. Footsore, exhausted, and half-starved, their morale at the lowest ebb, the men subsist on whatever bread they have saved from the last issue at Dolsen’s.

Tecumseh, meanwhile, has fought a rearguard action at the forks of the Thames – two frothing streams that remind him, nostalgically, of his last home, Prophetstown, where the Tippecanoe mingles its waters with those of the Wabash. In this strange northern land, hundreds of miles from his birthplace, he hungers for the familiar. His Indians tear the planks off the bridge at McGregor’s Creek and when Harrison’s forward scouts, under the veteran frontiersman William Whitley, try to cross on the sills, open fire from their hiding place in the woods beyond. Whitley, a sixty-three-year-old Indian fighter and Kentucky pioneer, has insisted on marching as a private under Harrison, accompanied by two black servants. Now he topples off the muddy timbers, falls twelve feet into the water, but manages to swim ashore, gripping his silver-mounted rifle. Major Eleazer Wood, the defender of Fort Meigs, sets up two six-pounders to drive the Indians off. The bridge is repaired in less than two hours, and the army pushes on.

That evening, Tecumseh reaches Christopher Arnold’s mill, twelve miles upriver from the forks. Arnold, a militia captain and an acquaintance from the siege of Fort Meigs, offers him dinner and a bed. He is concerned about his mill; the Indians have already burned McGregor’s. Tecumseh promises it will be spared. He sees no point in useless destruction; with the other mill gone, the white settlers must depend on this one.

In these last hours, fact mingles with myth as Tecumseh prepares for battle. Those whose paths cross his will always remember what was done, what was said, and hand it down to their sons and grandsons.

Young Johnny Toll, playing along the river bank near McGregor’s Creek, will never forget the hazel-eyed Shawnee who warned him, “Boy, run away home at once. The soldiers are coming. There is war and you might get hurt.”

Sixteen-year-old Abraham Holmes will remember the sight of Tecumseh standing near the Arnold mill on the morning of October 5, his hand at the head of his white pony: a tall figure, dressed in buckskin from neck to knees, a sash at his waist, his headdress adorned with ostrich plumes – waiting until the last of his men have passed by and the mill is safe. Holmes is so impressed that he will name his first-born Tecumseh.

Years from now Chris Arnold will describe the same scene to his grandson, Thaddeus. Arnold remembers standing by the mill dam, waiting to spot the American vanguard. It is agreed he will signal its arrival by throwing up a shovelful of earth. But Tecumseh’s eyes are sharper, and he is on his horse, dashing off at full speed, after the first glimpse of Harrison’s scouts. At the farm of Arnold’s brother-in-law, Hubble, he stops to perform a small act of charity – tossing a sack of Arnold’s flour at the front door to sustain the family, which is out of bread.

Lemuel Sherman’s sixteen-year-old son, David, and another friend, driving cows through a swamp, come upon Tecumseh, seated on a log, two pistols in his belt. The Shawnee asks young Sherman whose boy he is and, on hearing his father is a militiaman in Procter’s army, tells him: “Don’t let the Americans know your father is in the army or they’ll burn your house. Go back and stay home, for there will be a fight here soon.”

Years later when David Sherman is a wealthy landowner, he will lay out part of his property as a village and name it Tecumseh.

Billy Caldwell, the half-caste son of the Indian Department’s Colonel William Caldwell, will remember Tecumseh’s fatalistic remarks to some of his chiefs:

“Brother warriors, we are about to enter an engagement from which I shall not return. My body will remain on the field of battle.”

Long ago, when he was fifteen, facing his first musket fire against the Kentuckians, and his life stretched before him like a river without end, he feared death and ran from the field. Now he seems to welcome it, perhaps because he has no further reason to live. Word has also reached him that the one real love of his life, Rebecca Galloway, has married. She it was who introduced him to English literature. There have been other women, other wives; he has treated them all with disdain; but this sixteen-year-old daughter of an Ohio frontiersman was different. She was his “Star of the Lake” and would have married him if he had only agreed to live as a white man. But he could not desert his people. Now she is part of a dead past, a dream that could not come true, like his own shattered dream of a united Indian nation.

In some ways, Tecumseh seems more Christian than the Christians, with his hatred of senseless violence and torture. He is considerate of others, chivalrous, moral, and, in his struggle for his people’s existence, totally selfless. But he intends to go into battle as a pagan, daubed with paint, swinging his hatchet, screaming his war cry, remembering always the example of his elder brother Cheeseekau, the father figure who brought him up and, in the end, met death gloriously attacking a Kentucky fort, expressing the joy he felt at dying – not like an old woman at home but on the field of conflict where the fowls of the air should pick his bones.

Procter’s troops, who have had no rations since leaving Dolsen’s, are about to enjoy their first meal in more than twenty-four hours when the order comes to pack up and march – the Americans are only a short distance behind. Some cattle have already been butchered, but there is no time to cook the beef and there are no pans in which to roast it. Nor is there bread. Ovens have been constructed but again the baker has run off. Some of the men stuff raw meat into their mouths or munch on whatever crusts they still have from the last issue; the rest go hungry.

There is worse news. The Americans have seized all the British boats, captured the excess ammunition, tools, stores. The only cartridges the troops have are in their pouches. The officers attempt to conceal that disturbing information from their men.

The army marches two and a half miles. Procter appears and brings it to a halt. Here, with the river on his left and a heavy marsh on his right, in a light wood of beech, maple, and oak, he will make his stand.

It is not a bad position. His left flank, resting as it does on the high bank of the river, cannot be turned. His right is protected by the marsh. The General expects the invading army to advance down the road that cuts through the left of his position. He plants his only gun – a six-pounder – at this point to rake the pathway. The regulars will hold the left flank. The militia will form a line on their right. Beyond the militia, separated by a small swamp, will be Tecumseh’s Indians.

But why has Procter not chosen to make his stand farther upstream on the heights above Moraviantown, where his position could be protected by a deep ravine and the hundred log huts of the Christian Delaware Indians, who have lived here with their Moravian missionaries since fleeing Ohio in 1792? It is to this village that Procter brought his main ordnance and supplies. Why the sudden change of plan?

Once again the Indians have dictated the battle. They will not fight on an open plain; that is not their style. Procter feels he has no choice but to anticipate their wishes.

His tactics are simple. The British will hold the left while the Indians, moving like a door on a hinge, creep forward through the thicker forest on the right to turn Harrison’s flank.

There are problems, however, and the worst of these is morale. The troops are slouching about, sitting on logs and stumps. They have already been faced about once, marched forward and then back again for some sixty paces, grumbling about “doing neither one thing or another.” Almost an hour passes before they are brought to their feet and told to form a line. This standard infantry manoeuvre is accomplished with considerable confusion, compounded by the fact that Procter’s six hundred men are too few to stand shoulder to shoulder in the accepted fashion. The line develops into a series of clusters as the troops seek to conceal themselves behind trees. Nobody, apparently, thinks to construct any sort of bulwark – entrenchments, earthworks, or a barricade of logs and branches – which might impede the enemy’s cavalry. No one appears to notice that on the British side of the line there is scarcely any underbrush. But then, all the shovels, axes, and entrenching tools have been lost to the enemy.

The troops stand in position for two and a half hours, patiently waiting for the Americans to appear. They are weak from hunger, exhausted from the events of the past weeks. They have had no pay for six months, cannot even afford soap. Their clothes are in rags, and they have been perennially short of greatcoats and blankets. They are overworked, dispirited, out of sorts. Some have been on garrison duty, far away from home in England, for a decade. They cannot see through the curtain of trees but have heard rumours that Harrison has ten thousand men advancing to the attack. Many believe Procter is more interested in saving his wife and family than in saving them; many believe they are about to be cut to pieces and sacrificed for nothing. And so they wait – for what seems an eternity.

Tecumseh rides up. The men, he tells Elliott, seem to him to be too thickly posted; they will be thrown away to no advantage. Procter obediently robs his line to form a second, one hundred yards behind, with a corps of dragoons in reserve. Now the Shawnee war chief rides down the ragged line, clasping hands with the officers, murmuring encouragement in his own language. He has a special greeting for John Richardson, whom he has known since childhood. Richardson notes the fringed deerskin ornamented with stained porcupine quills, the ostrich feathers (a gift from the Richardson family), and most of all the dark, animated features, the flashing hazel eyes. Whenever in the future he thinks of Tecumseh – and he will think of him often – that is the picture that will remain: the tall sturdy chief on the white pony, who seems now to be in such high spirits and who genially tells Procter, through Elliott, to desire his men to be stout-hearted and to take care the Long Knives do not seize the big gun.

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON, having destroyed Procter’s gunboats and supplies, has crossed the Thames above Arnold’s mill in order to reach the right bank along which the British have been retreating. The water at the ford is so deep that the men hesitate until Perry, in his role as Harrison’s aide, rides through the crowd, shouts to a foot soldier to climb on behind, and dashes into the stream, calling on Colonel Johnson’s mounted volunteers to follow his example. In this way, and with the aid of several abandoned canoes and keel boats, the three thousand foot soldiers are moved across the river in forty-five minutes.

William Whitley, the veteran scout, seeing an Indian on the opposite side, shoots him, swims his horse back across, and scalps the corpse. “This is the thirteenth scalp I have taken,” he tells a friend, “and I’ll have another by night or lose my own.”

As the army forms up on the right bank, a message arrives for Harrison. A spy has reported that the British are not far ahead, aiming for Moraviantown. Harrison rides up to Johnson, tells him that foot soldiers will not be able to overtake Procter until late in the day, asks him to push his mounted regiment forward to stop the British retreat.

“If you cannot compel them to stop without an engagement, why FIGHT them, but do not venture too much,” Harrison orders.

Johnson moves his men forward at a trot. Half a mile from the British line his forward scouts capture a French-Canadian soldier. The prisoner insists that Procter has eight hundred men supported by fourteen hundred Indians. When Johnson reveals he has only one thousand followers, his informant bursts into tears, begs him to retire. But Johnson has no intention of retreating. He sends back a message to Harrison that the British have halted and are only a few hundred yards distant. If they venture to attack, his men will charge them.

Procter does not attack, and the two armies remain within view of one another, motionless, waiting.

A quarter of an hour passes. Harrison rides up, sends Eleazer Wood forward to examine the situation through his spyglass. Behind him, the American column – eleven regiments supported by artillery – stretches back for three miles. Harrison holds a council of war on horseback. He sees at once that Procter has a good position and divines the British strategy: they will use the Indians on his left on the edge of the morass to outflank him. That he must frustrate. He will attempt to hold the Indians back with a strong force on his left and attack the British line with a bayonet charge through the woods. At the same time Johnson’s mounted men will splash through the shallow swamp that separates the British from the Indians and fall on Tecumseh’s tribesmen.

Harrison forms up his troops in an inverted L, its base facing the British regulars. Shelby is posted at the left end of the base (the angle of the L). Harrison takes a position on the right, facing Procter. The honour of leading the bayonet charge goes to Brigadier-General George Trotter, a thirty-four-year-old veteran. It is a signal choice, for a high proportion of Trotter’s men come from the same Kentucky counties that bore the brunt of the Frenchtown massacre.

An hour and a half passes while Harrison forms his troops. The British, peering through the oaks, the beeches, and the brilliant sugar maples, can catch only glimpses of the enemy, three hundred yards distant. The Americans, waiting to attack, have a better view of the British in their scarlet jackets.

Meanwhile, Richard Johnson has sent Captain Jacob Stucker to examine the shallow swamp through which his troops must gallop in their attack on the Indians. Stucker returns with disappointing news: the swamp is impassable. Finally, the General speaks:

“You must retire, Colonel, and act as a corps of reserve.”

But Johnson has a different idea:

“General Harrison, permit me to charge the enemy and the battle will be won in thirty minutes.” He means the British – not the Indians.

Harrison considers. The redcoats are spread out in open formation with gaps between the clusters of men. The woods are thick with trees, but there is little underbrush. He knows that Johnson has trained his men to ride through the forests of Ohio, firing cartridges to accustom the horses to the sound of gunfire. Most have ridden horseback since childhood; all are expert marksmen.

“Damn them! Charge them!” says Harrison, and changes the order of battle on the spot.

It is a measure, Harrison will later declare, “not sanctioned by anything that I had seen or heard of.” But he is convinced that this unorthodox charge will catch the British unprepared.

Now Stucker comes back with welcome news. He has found a way through the intervening swamp. It will not be easy, for the ground is bad. Johnson turns to his brother, James, his second-in-command.

“Brother, take my place at the head of the first battalion. I will cross the swamp and fight the Indians at the head of the second battalion.” He explains his reason: “You have a family, I have none.”

In the brief lull that follows, one of Harrison’s colonels, John Calloway, rides out in front of his regiment and in a stentorian voice, shouts:

“Boys, we must either whip these British and Indians or they will kill and scalp every one of us. We cannot escape if we lose. Let us all die on the field or conquer.”

Procter’s repeated threat – that he cannot control the Indians – has been turned against him. He has so convinced the Americans that a massacre will follow a British victory that they are prepared, if necessary, for a suicidal attack.

The bugle sounds the charge. Seated on his horse halfway between the two British lines, Procter hears the sound and asks his brigade major, John Hall, what it means. The bugle sounds again, closer.

“It’s the advance, Sir,” Hall tells him.

An Indian scout, Campeaux, fires his musket. Without orders, the entire British front line discharges a ragged volley at the advancing horsemen.

In spite of their training, the horses recoil in confusion.

Procter looks toward the six-pounder on his left. “Damn that gun,” he says. “Why doesn’t it fire?”

But the British horses have also been startled by the volley. They rear back, become entangled in the trees, taking the six-pounder with them.

James Johnson rallies his men and charges forward as the second line of British defenders opens fire.

“Charge them, my brave Kentuckians!” Harrison cries in his florid fashion as the volunteers dash forward, yelling and shouting.

“Remember the Raisin!” someone shouts, and the cry ripples across the lines: “Remember the Raisin! Remember the Raisin!”

The volunteers hit the left of the British line. It crumbles. Captain Peter Chambers, one of the heroes of the siege of Fort Meigs, sees his men tumbling in all directions, tries vainly to rally them, finds himself swept back by the force of the onslaught.

“Stop, 41st, stop!” Procter shouts. “Why do you not form? What are you about? For shame. For shame on you!”

The force of the charge has taken Johnson’s horsemen right through both British lines. Now they wheel to their left to roll up the British right, which is still holding.

“For God’s sake, men, stand and fight!” cries a sergeant of the 41st. Private Shadrach Byfield, in the act of retreating, hears the cry, turns about, gets off a shot from his musket, then flees into the woods.

Not far away stands John Richardson, an old soldier at sixteen, survivor of three bloody skirmishes. A fellow officer points at one of the mounted riflemen taking aim at a British foot soldier. Richardson raises his musket, leans against a tree for support, and before the mounted man can perfect his aim drops him from his horse. Now he notes an astonishing spectacle on his right. He sees one of the Delaware chiefs throw a tomahawk at a wounded Kentuckian with such precision and force that it opens his skull, killing him instantly. The Delaware pulls out the hatchet, cuts an expert circle around the scalp; then, holding the bloody knife in his teeth, he puts his knee on the dead man’s back, tears off the scalp, and thrusts it into his bosom, all in a matter of moments. This grisly scene is no sooner over than the firing through the woods on Richardson’s left ends suddenly, and the order comes to retreat.

Procter, too, is preparing to make off. The gun crew has fled; the Americans have seized the six-pounder. Hall warns him that unless they move swiftly they will both be shot.

“Clear the road,” Hall orders, but the road is clogged with fleeing redcoats. He suggests to the General that they should take to the woods; but Procter, stunned by the suddenness of defeat, does not appear to hear him. No more than five minutes have passed since Harrison’s bugle sounded.

“This way, General, this way,” says Hall patiently, like a parent leading a child. The General follows obediently. A little later he finds his voice:

“Do you not think we can join the Indians?” For Tecumseh’s force on the right of the shattered British line is still fighting furiously.

“Look there, Sir,” says Hall, pointing to the advancing Americans. “There are mounted men betwixt you and them.” James Johnson’s charge has cut Procter’s army in two.

They are on the road, riding faster now, for the Americans are in hot pursuit. Procter is desperate to escape the wrath of the Kentucky volunteers, whose reputation is as savage as that of the Potawatomi who slaughtered their countrymen at the River Raisin. For all he knows they may flay him alive before Harrison can stop them.

As Captain Thomas Coleman of the Provincial Dragoons catches up, the General gasps out that he is afraid he will be captured. Coleman reassures him: some of his best men will be detailed to guard him. The General gallops on with the sound of Tecumseh’s Indians, still holding, echoing in his ears.

As James Johnson’s men drive the British before them, his brother’s battalion plunges through the decaying trees and tangled willows of the small swamp that separates the Indians from their white allies. Richard Johnson’s plan is brutal. He has called for volunteers for what is, in effect, a suicide squad – a “Forlorn Hope,” in the parlance of both the British and the American armies. This screen of twenty bold men will ride ahead of the main body to attract the Indians’ fire. Then, while the tribesmen are reloading, the main body will sweep down upon them.

There is no dearth of volunteers. The grizzled Whitley, a fresh scalp still dangling from his belt, will lead the Forlorn Hope. And Johnson will ride with them.

Off they plunge into the water and mud, into a hail of musket balls. Above the shattering dissonance of the battle another sound is heard – clear, authoritative, almost melodic – the golden voice of Tecumseh, urging his followers on to victory. Johnson’s tactic is working: the Indians have concentrated all their fire on the Forlorn Hope, and with devastating results – fifteen of the twenty, including William Whitley, are dead or mortally wounded.

But Johnson faces a problem. The mud of the swamp has risen to the saddle girth of the horses. His men cannot charge. Bleeding from four wounds, he orders them to dismount and attack. An Indian behind a tree fires again, the ball striking a knuckle of Johnson’s left hand, coming out just above the wrist. He grimaces in pain as his hand swells, becomes useless. The Indian advances, tomahawk raised. Johnson, who has loaded his pistol with one ball and three buckshot, draws his weapon and fires, killing his assailant instantly. Not far away lies the corpse of William Whitley, riddled with musket balls.

Beyond the protecting curtain of gunsmoke, the battle with the Indians rages on as Shelby moves his infantry forward to support the dismounted riflemen. Oliver Hazard Perry, carrying one of Harrison’s dispatches to the left wing, performs a remarkable feat of horsemanship as his black steed plunges to its breast in the swamp. The Commodore presses his hands to the saddle, springs over the horse’s head to dry land; the horse, freed of its burden, heaves itself out of the swamp with a mighty snort; as it bounds forward, Perry clutches its mane and vaults back into the saddle without checking its speed or touching bridle or stirrup.

Word spreads that Richard Johnson is dead. An old friend, Major W.T. Barry, riding up from the rear echelon to examine the corpse, meets a group of soldiers bearing the Colonel back in a blanket.

“I will not die, Barry,” Johnson assures him. “I am mightily cut to pieces, but I think my vitals have escaped.” One day he will be vice-president.

Behind him, the cacophony of battle continues to din into his ears as Shelby’s force presses forward through the trees. The volume rises in intensity: the advancing Kentuckians shouting their vengeful battle cry; the Indians shrieking and whooping; wounded men groaning and screaming; horses neighing and whinnying; muskets and rifles shattering ear drums; bugles sounding; cannon firing.

The smoke of battle lies thickly over forest and swamp, making ghosts of the dim, painted figures who appear for an instant from the cover of a tree to fire a weapon or hurl a tomahawk, then vanish into the gloom. They are not real, these Indians, for their faces can be seen only in death. Which are the leaders, which the followers? One man, the Kentuckians know, is in charge: they can hear Tecumseh’s terrible battle cry piercing the ragged wall of sound. For five years they have heard its echo, ever since the Shawnee first made his presence felt in the Northwest. Yet that presence has always been spectral; no Kentuckian on the field this day – no white American, in fact, save Harrison – has ever seen the Shawnee chief or heard his voice until this moment. He is a figure of legend, his origins clouded in myth, his persona a reflection of other men’s perception. Johnson’s riders, firing blindly into the curtain of trees, hating their adversary and at the same time admiring him, are tantalized by his invisibility.

Suddenly comes a subtle change in the sound. Private Charles Wickliffe, who has been timing the battle, notices it: something is missing. Wickliffe, groping for an answer, comes to realize that he can no longer discern that one clear cry, which seemed to surmount the dissonance. The voice of Tecumseh, urging on his followers, has been stilled. The Shawnee has fallen.

The absence of that clarion sound is as clear as a bugle call. Suddenly the battle is over as the Indians withdraw through the underbrush, leaving the field to the Kentuckians. As the firing trails off, Wickliffe takes out his watch. Exactly fifty-five minutes have elapsed since Harrison ordered the first charge.

As the late afternoon shadows gather, a pall rises over the bodies of the slain. There are redcoats here, their tunics crimsoned by a darker stain, and Kentuckians in grotesque attitudes that can only be described as inhuman, and Indians, staring blankly at the sky, including several minor chieftains, one dispatched by Johnson, another by Whitley.

But one corpse is missing. Elusive in life, Tecumseh remains invisible in death. No white man has ever been allowed to draw his likeness. No white man will ever display or mutilate his body. No headstone, marker, or monument will identify his resting place. His followers have spirited him away to a spot where no stranger, be he British or American, will ever find him – his earthly clay, like his own forlorn hope, buried forever in a secret grave.

JOHN RICHARDSON, fleeing from James Johnson’s riders, charges through the woods with his comrades, loses his way, finds himself unexpectedly on the road now clogged with wagons, discarded stores and clothing, women and children. Five hundred yards to his right he sees the main body of his regiment, disarmed and surrounded by the enemy. Instinctively, he and the others turn left, only to run into a body of American cavalry, the men dismounted, walking their horses.

Their leader, a stout elderly officer dressed like his men in a Kentucky hunting jacket, sees them, gallops forward brandishing his sword and shouting in a commanding voice:

“Surrender, surrender! It’s no use resisting. All your people are taken and you’d better surrender.”

This is Shelby. Richardson, whose attitude towards all Americans is snobbishly British Canadian, thinks him a vulgar man who looks more like one of the army’s drovers than the governor of a state – certainly not a bit like the chief magistrate of one of His Majesty’s provinces.

He swiftly buries his musket in the deep mud to deny it to the enemy and surrenders. As the troops pass by, one tall Kentuckian glances over at the diminutive teen-ager and says: “Well, I guess now, you tarnation little Britisher, who’d calculate to see such a bit of a chap as you here?” Richardson never forgets that remark, which illustrates the language gulf between the two English-speaking peoples who share the continent.

Shadrach Byfield at this moment, having fled into the woods at the same time as Richardson, has encountered a party of British Indians who tell him Tecumseh is dead. They want to know whether the enemy has also taken Moraviantown and ask Byfield whether he can hear American or British accents up ahead. At the forest’s edge, Byfield hears a distinctive American voice cry, “Come on, boys!” The party retreats at once. Terrified that the Indians will kill him, he gives away what tobacco he has in his haversack and prepares to spend the night in the woods.

Major Eleazer Wood is in full pursuit of Procter, but the General eludes him, stopping only briefly at Moraviantown and pressing on to Ancaster, so fatigued he cannot that evening write a coherent account of the action. Wood has to be content with capturing his carriage containing his sword, hat, trunk, and all his personal papers, including a packet of letters from his wife, written in an exquisite hand.

Moraviantown’s single street is clogged with wagons, horses, and half-famished Kentuckians. The missionary’s wife, Mrs. Schnall, works all night baking bread for the troops, some of whom pounce on the dough and eat it before it goes into the oven. Others upset all the beehives, scrambling for honey, and ravage the garden for vegetables, which they devour raw.

Richardson and the other prisoners fare better. Squatting around a campfire in the forest, they are fed pieces of meat toasted on skewers by Harrison’s aides, who tell the British that they deplore the death of the much-admired Tecumseh.

Now begins the long controversy over the circumstances of the Shawnee’s end. Who killed Tecumseh? Some give credit to Whitley, whose body was found near that of an Indian chief; others, including Governor Shelby, believe that a private from Lincoln County, David King, shot him. Another group insists that the Indian killed by Richard Johnson was the Shawnee; that will form the most colourful feature of Johnson’s subsequent campaign for the vice-presidency.

But nobody knows or will ever know how Tecumseh fell. Only two men on the American side know what he looks like – Harrison, his old adversary, and the mixed-blood Anthony Shane, the interpreter, who knew him as a boy. Neither is able to say with certainty that any of the bodies on the field resembles the Indian leader.

The morning after the battle, David Sherman, the boy who encountered Tecumseh in the swamp, finds one of his rifled flintlock pistols on the field. That same day, Chris Arnold comes upon a group of Kentuckians flaying the body of an Indian to make souvenir razor strops from the skin.

“That’s not Tecumseh,” Arnold tells them.

“I guess when we get back to Kentucky they will not know his skin from Tecumseh’s,” comes the reply.

In death, as in life, the Shawnee inspires myth. There are those who believe he was not killed at all, merely wounded, that he will return to lead his people to victory. It is a wistful hope. “Skeletons” of Tecumseh will turn up in the future. “Authentic” graves will be identified, then rejected. But the facts of his death and his burial are as elusive as those of his birth, almost half a century before.

As the Americans bury their dead and those of their enemy in two parallel trenches, Shadrach Byfield moves through the wilderness with the Indians, still fearful that he will be killed by his new companions. Toward sunset on his second night in the wild, to Byfield’s relief and delight the party stumbles upon one of his comrades, also drifting about in the woods. That night they sleep out in the driving rain, existing on a little flour and a few potatoes. The following night they find an Indian village where they are treated kindly and fed pork and corn. At last, after a further twenty-four hours of wandering, their shoes now in shreds, they run into a group of fifty escapees whom Lieutenant Richard Bullock has gathered together. With Bullock in charge, the remnants of the 41st make their way to safety.

John Richardson, meanwhile, is marched back to the Detroit River with six hundred prisoners. Fortunately for him, his grandfather, John Askin of Amherstburg, has a son-in-law, Elijah Brush, who is an American militia colonel at Detroit. Askin writes to his daughter’s husband to look after his grandson. As a result, Richardson, instead of being sent up the Maumee with the others, is taken to Put-in Bay by gunboat, where he runs into his own father, Dr. Robert Richardson, an army surgeon captured by Perry and assigned to attend the wounded Captain Barclay.

The double victories on Lake Erie and the Thames tip the scales of war. For all practical purposes the conflict on the Detroit frontier is ended. At Twenty Mile Creek on the Niagara peninsula, Major-General Vincent, expecting Harrison to follow up his victory, falls into a panic, destroys stocks of arms and supplies, trundles his invalid army back to the protection of Burlington Heights. Of eleven hundred men, eight hundred are on sick call, too ill to haul the wagons up the hills or through the rivers of mud that pass for roads.

De Rottenburg is prepared to let all of Upper Canada west of Kingston fall to the Americans, but the Americans cannot maintain their momentum. Harrison’s own supply lines are stretched taut; the Thames Valley has been scorched of fodder, grain, and meat; his six-month volunteers are clamouring to go home. Harrison is a captive of America’s hand-to-mouth recruiting methods. He cannot pursue the remnants of Procter’s army, as military common sense dictates. Instead, he moves back down the Thames, garrisons Fort Amherstburg, and leaves Brigadier-General Duncan McArthur in charge of Detroit.

The British still hold a key outpost in the Far West – the captured island of Michilimackinac, guarding the route to the fur country. It is essential that the Americans seize it; with Perry’s superior fleet that should not be difficult. But the Canadian winter frustrates this plan. For that adventure the Americans must wait until spring. Instead, Harrison takes his regulars and moves east to Fort George, from which springboard he hopes to attack Burlington Heights.

Once again victory bonfires light up the sky; songs written for the occasion are chorused in the theatres; Harrison is toasted at every table; Congress strikes the mandatory gold medal. One day, William Henry Harrison will be president. An extraordinary number of those who fought with him will also rise to high office. One will achieve the vice-presidency, three will rise to become governors of Kentucky, three more to lieutenant-governor. Four will go to the Senate, at least a score to the House.

For Henry Procter there will be no accolades. A court martial the following year finds him guilty of negligence, of bungling the retreat, of errors in tactics and judgement. He is publicly reprimanded and suspended from rank and pay for six months.

Had Procter retreated promptly and without encumbrance, he might have joined Vincent’s Centre Division and saved his army. But it is the army he blames for all his misfortunes, not himself. In his report of the battle and his subsequent testimony before the court, he throws all responsibility for defeat on the shoulders of the men and officers serving under him. The division’s laurels, he says, are tarnished “and its conduct calls loudly for reproach and censure.” But in the end it is Procter’s reputation that is tarnished and not that of his men. To the Americans he remains a monster, to the Canadians a coward. He is neither – merely a victim of circumstances, a brave officer but weak, capable enough except in moments of stress, a man of modest pretensions, unable to make the quantum leap that distinguishes the outstanding leader from the run-of-the-mill: the quality of being able in moments of adversity to exceed one’s own capabilities. The prisoner of events beyond his control, Procter dallied and equivocated until he was crushed. His career is ended.

He leaves the valley of the Thames in a shambles. Moraviantown is a smoking ruin, destroyed on Harrison’s orders to prevent its being used as a British base. Bridges are broken, grist mills burned, grain destroyed, sawmills shattered. Indians and soldiers of both armies have plundered homes, slaughtered cattle, stolen private property.

Tecumseh’s confederacy is no more. In Detroit, thirty-seven chiefs representing six tribes sign an armistice with Harrison, leaving their wives and children as hostages for their good intentions. The Americans have not the resources to feed them, and so women and children are seen grubbing in the streets for bones and rinds of pork thrown away by the soldiers. Putrefied meat, discarded in the river, is retrieved and devoured. Feet, heads, and entrails of cattle – the offal of the slaughterhouses – are used to fill out the meagre rations. On the Canadian side, two thousand Indian women and children swarm into Burlington Heights pleading for food.

Kentucky has been battling the Indians since the days of Daniel Boone. Now the long struggle for possession of the Northwest is over; that is the real significance of Harrison’s victory. The proud tribes have been humbled; the Hero of Tippecanoe has wiped away the stain of Hull’s defeat; and (though nobody says it) the Indian lands are ripe for the taking.

The personal struggle between Harrison and Tecumseh, which began at Vincennes, Indiana Territory, in 1810, has all the elements of classical tragedy. And, as in classical tragedy, it is the fallen hero and not the victor to whom history will give its accolade. It is Harrison’s fate to be remembered as a one-month president, forever to be confused with a longer-lived President Harrison – his grandson, Benjamin. But in death as in life, there is only one Tecumseh. His last resting place, like so much of his career, is a mystery; but his memory will be for ever green.