![]()

One of the pleasantest crossings any of us had.

—CALEB DAVIS1

![]()

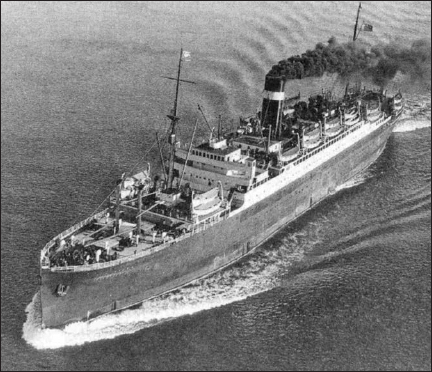

By midmorning Monday, 4 September, after all of the Athenia survivors in lifeboats had been picked up, a fourth rescue ship arrived. The U.S. Maritime Commission freighter City of Flint had also received the distress signal sent out on Sunday evening and responded as well. The City of Flint was a 4,963-ton general cargo freighter built by the American International Shipbuilding Corporation at Hog Island, Pennsylvania, and launched in 1920. She had a complement of about ten officers and thirty crewmembers. She had sailed from New York in August under contract to the United States Lines and had unloaded and loaded cargo in Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, and Glasgow and was homeward bound for New York when the SOS was picked up. However, the City of Flint was destined to play a distinctive role in the rescue of the Athenia victims and the early incidents of the war.

The ship’s skipper was Capt. Joseph A. Gainard, a merchant sailor from Chelsea, Massachusetts. He had served in the U.S. Navy during the Great War and was an officer on the troopship USS President Lincoln when she was torpedoed while returning to the United States almost empty in May of 1918. After the war, Gainard left the Navy to work in the Merchant Marine service, where he rose in rank to that of master and where he had the distinction of having to deal with a mutiny in 1937. In March of 1939 Captain Gainard was given command of the City of Flint and began the first of several voyages to and from Europe. Late August found him in Manchester, Liverpool, and Dublin, where he was approached by a number of Americans, stranded as the war crisis unfolded, who asked if they could book passage back to the United States on the City of Flint. Gainard told them categorically no—the City of Flint was a freighter with no facilities for passengers. However, when Captain Gainard brought his ship into Glasgow on Thursday, 31 August, to pick up his last cargo, which included coils of rope, wool, and 30,000 cases of Scotch whiskey, he was given a message to telephone the Maritime Commission office in London. Gainard called Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, whom he knew well, instead, and talked to the ambassador’s secretary. The ambassador had also been approached by a large number of Americans and their families in the United States to help arrange passage back to the United States, including A. D. Simpson and Burke Baker of Houston, Texas, and their friend Jesse H. Jones, the chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Kennedy had done as much as he could to get people booked on the remaining passenger liners heading for North America, like the Athenia; however, he had also used his influence as the former head of the U.S. Maritime Commission to make arrangements for up to thirty people to sail on the City of Flint. Neither Captain Gainard nor his crew were happy with this, but as Gainard himself put it, “After all, I suppose it was my duty to uphold the Ambassador to my country—particularly when he was Joseph P. Kennedy, and a New Englander, and a mighty fine individual in spite of his high office.”2

Before he left the shipping agent’s office Captain Gainard was introduced to one of the four Texas college girls who had been booked on his ship, Susan Harding of Fort Worth. The ambassador’s secretary had not mentioned that any of the passengers were women. Miss Harding was undeterred by his attempts to discourage her from sailing on a freighter. Gainard concluded that he could discourage the college girls by inviting them on to the City of Flint so that they could have a good look around and see for themselves that the ship was not really suitable. “The girls went all over the ship, but instead of being upset with the things they saw, they seemed to grow more enthusiastic about us than they had been before they came aboard.” He brought them into the wardroom “with my sternest face,” to give them a good talking to, but the steward served them first coffee and then cakes, and the chief officer joined the conversation. Finally when the steward had served the third round of cakes, “I had gotten ashamed of the idea of trying to discourage them,” the captain admitted, and he began thinking of how to make their trip as pleasant as possible. The conversation in the wardroom became increasingly cordial. “There was more laughter in that saloon that evening than the City of Flint had ever heard before.” He concluded the girls were “absolutely irrepressible” and “nice” and he and the crew were going to enjoy having them. In fact the girls invited their friends who were booked to sail on the Athenia, which was moored across the pier from the City of Flint, to come and join them for coffee. Susan Harding cabled her relieved father, “SAILING FREIGHTER NEW YORK.”3

When he got back to the ship Captain Gainard found that other passengers, Professor Harold H. Plough and Professor George Childs, both from Amherst College in Massachusetts, and several others, were already on board looking at the vessel. Gainard and his officers and men realized that taking on twenty-nine passengers was going to mean that they would all be put to some inconvenience, and it was clear that women on board would create special problems. The nine women passengers, including the five Texas college girls (a fifth was added), were placed in the captain’s room (with a private bath), the chief officer’s room, and initially in the chartroom. Additional sleeping quarters—bunks—would also have to be constructed. Wooden flooring was put down on the steel deck plates and the cots were set up in the shelter deck where the male passengers would sleep. Cots, sheets, pillows, blankets, and mattresses were ordered—six sets for each passenger in case they got wet. Electric lights were strung up to provide illumination. Bathroom facilities would be overtaxed. Additional life preservers had to be made. Although Maritime Commission ships were generously provisioned, the captain had his steward calculate what additional food supplies would be needed. Captain Gainard also asked Susan Harding to go into Glasgow and buy substantial quantities of Coca-Cola, cookies, and crackers, and she took the liberty of getting quite a bit of candy as well.4 All of this planning and preparation was providential in view of the disaster that lay ahead.

A view of the Athenia under way at sea, showing clearly the layout of the port side lifeboats. The ship was built on the Clyde in 1923 by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company to the specifications of a Cunard Class A vessel, and thus resembled a number of other passenger liners. PAUL STRATHDEE DONALDSON LINE COLLECTION

The attractive tourist-class dining room in the Athenia, showing the stairway toward which passengers groped their way in the dark after the ship had been hit by the torpedo STEAMSHIP HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The lifeboat positions are shown by their numbers. AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

In a photograph taken by Paul Vanderbilt in the summer of 1937, passengers on the Athenia are seen examining the davits of the port side lifeboats 12 and 12A on the promenade deck. Lifeboat 14 on the bridge deck can be seen in the upper left-hand corner. The lifeboat covers have been furled, revealing the grab lines along the sides of each boat. PAUL VANDERBILT, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

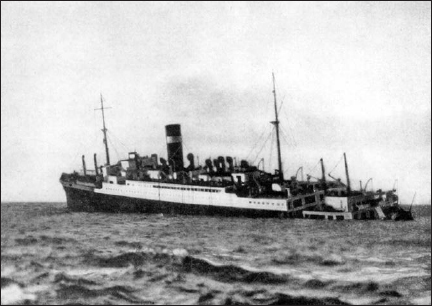

View of the stricken Athenia on the morning of 4 September 1939, well down in the stern and the bridge deck clearly awash. The ship sank at about 11:00 a.m. The falls for lowering the lifeboats can be seen dangling from the davits. Despite claims that the U-boat had fired its deck gun at the masts, they seem to be intact. MARINEQUEST

The U-30 returning to port, probably in 1940. The submarine was a 206-foot Type VIIA U-boat; the fast-firing 3.5-inch deck gun can be seen forward of the conning tower. The U-30 was built by A. G. Weser in Bremen in 1936. It survived the war, to be scuttled on 4 May 1945 as the conflict in Europe was coming to an end. MARINEQUEST

Chief Officer Barnet Mackenzie Copland, O.B.E., was a Scot who had a long career with the Donaldson Line. Copland had the misfortune of having a second ship, the Esmond, torpedoed by a U-boat commanded by Lemp on 9 May 1941. W. W. NORTON

Captain James Cook, O.B.E, was from a Glasgow maritime family. He served in the Royal Navy during the Great War and joined the Donaldson Line in 1919, where he enjoyed a long career. W. W. NORTON

Fritz-Julius Lemp and Admiral Karl Dönitz on the deck of the U-30 at the U-boat base at Wilhelmshaven in August 1940. Lemp is not in a dress uniform and has clearly just returned from sea duty. He is wearing the Iron Cross, which had just been presented to him by Dönitz. BUNDESARCHIV, BARCH, BILD 101II-MN-1365-27/PETER

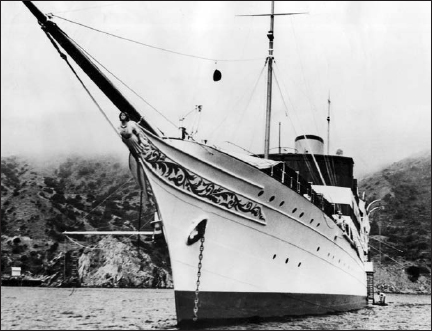

A view of the Southern Cross in 1935 anchored off Catalina Island, on the California coast, while still owned by Howard Hughes. Built in Glasgow in 1930, it was regarded as the largest private yacht in the world. Before the war was over Axel Wenner-Gren gave the Southern Cross to the Mexican navy, where it became the training ship Zaragoza. CORBISIMAGES

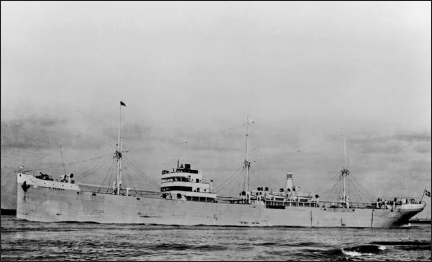

The Knute Nelson was a freighter built in Denmark in 1926 for the Norwegian steamship line, Fred. Olsen & Company. The ship was eventually sunk by torpedoes off the coast of Norway in September 1944. FRED. OLSEN & CO.

HMS Electra, shown here, was built at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1934. Electra, Escort, and Fame were all Escapade- or E-class destroyers and were roughly similar in looks. All three destroyers saw distinguished service in the war, both Electra and Escort being lost in action. CRONSTON FINE ARTS

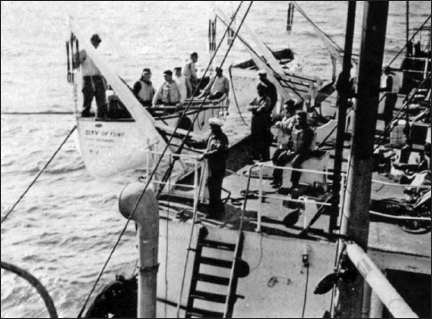

The City of Flint was built in shipyards at Hog Island, Pennsylvania, in 1920, and in 1939 the ship was operated by the U.S. Maritime Commission. The City of Flint had the American flag painted on the sides in anticipation of U.S. neutrality in the war. The ship had taken on the Athenia survivors on 4 September and is here on its way to Halifax. The City of Flint was later torpedoed in the Atlantic while steaming in a convoy to North Africa in January 1943. NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES, JOHN F. ROGERS COLLECTION, 1995-370, NO. 51

Survivors line the rail of the Knute Nelson about to transfer to the tender to be brought into Galway. The young boy in the center of the picture, Donald A. Wilcox, was recognized by his father in Canada when this picture appeared in the Montreal Gazette. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND, INDH 3395

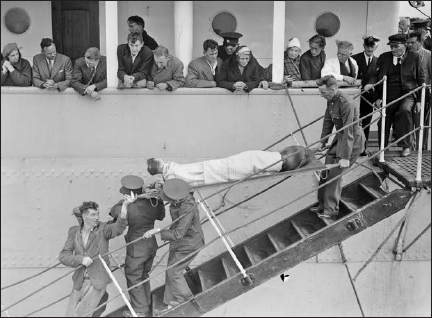

The badly injured survivors were the first to be transferred to the tender, assisted by Irish soldiers from the 1st Infantry (Irish-speaking) Battalion. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND, INDH 3389

One of the cooks from the Athenia, who was badly scalded when the torpedo exploded below the galley, sending pots of boiling cooking oil flying IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51010/GETTYIMAGES

An infant, whose tiny foot is just visible, is wrapped in a blanket and carried off the Knute Nelson by an Irish soldier, followed by his mother. IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51012/GETTYIMAGES

Rowena Simpson and Genevieve Morrow from Houston and Betty Jane Stewart from Dallas, three of the University of Texas girls on the tender heading for Galway. Seated on the left was Robert F. Townsend, also from Houston. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND, INDH 3392

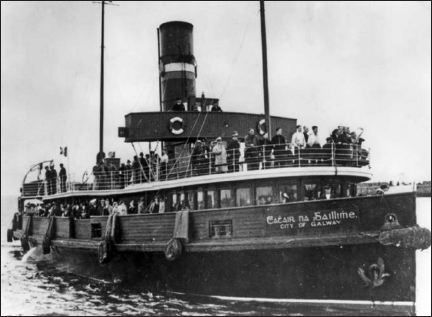

The Galway tender Cathair Na Gaillimhe coming into port can be seen to be carrying many survivors, as well as officials from the city, Irish soldiers and nurses, and the U.S. minister to Ireland, John C. Cudahy. IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51007

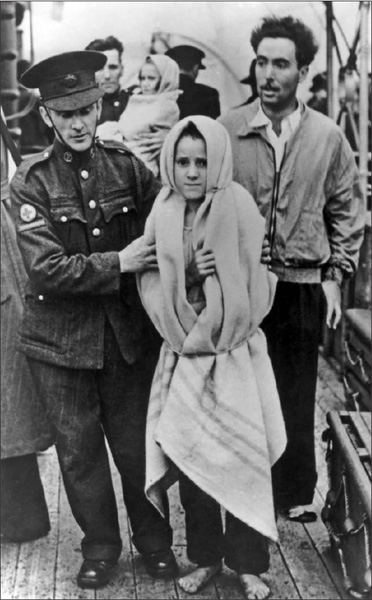

A child, barefoot and wrapped in a blanket, is escorted ashore by an Irish soldier. IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51015/GETTYIMAGES

A young woman, in borrowed clothes and makeshift footwear, reaches land in some distress. IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51011/GETTYIMAGES

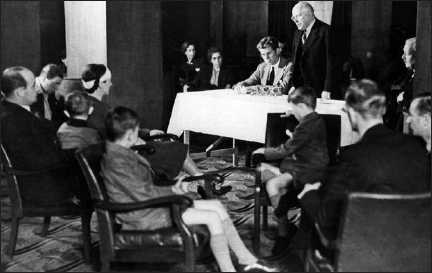

John F. Kennedy and the lord provost of Glasgow, Patrick J. Dollan, talking with survivors. The lord provost moved quickly to provide facilities for the survivors. JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY, PC 74

The U.S. consul general, Leslie A. Davis, and John F. Kennedy, the son of Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, talked with survivors in Glasgow and attempted to assure them that they would be brought back to America safely. One of the survivors can be seen with a bandage around her head. Consul Davis was also linked to the City of Flint through his son, Caleb Davis, who had arranged for passage home on the freighter and worked to help create facilities for the Athenia survivors when they joined the ship. APIMAGES, 390909043

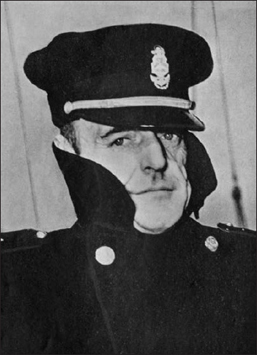

Capt. Joseph A. Gainard dressed in a watch coat. Picking up Athenia survivors and having the City of Flint seized by the Germans were just the first of several adventures Captain Gainard experienced in the early months of the war. By the end of 1940 he had written his memoirs, Yankee Skipper, returned to service in the U.S. Navy, and been awarded the Navy Cross. HARPERCOLLINS

City of Flint lifeboat being lowered to help bring survivors over from the Southern Cross. Captain Gainard sent his biggest crewmen in the boat. As he put it, “There is something encouraging about a six-footer at an oar.” HARPERCOLLINS

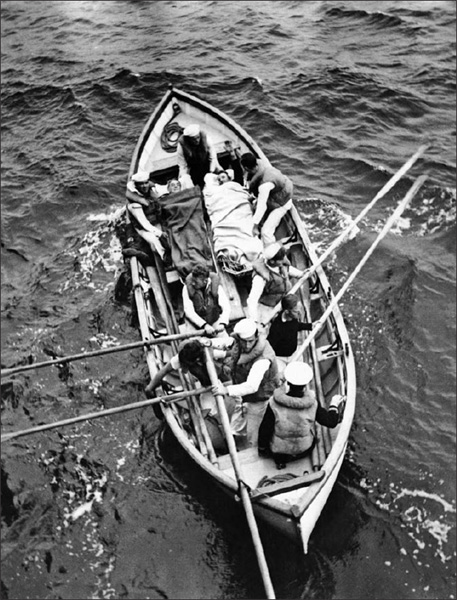

A lifeboat from the Athenia carrying survivors from the Southern Cross to the City of Flint. The sailors in uniform are part of the crew of the Southern Cross. In addition to the Jacob’s ladder descending from the side of the City of Flint, it can be seen that the elderly woman on the left is also supported by a rope sling. IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, HU 51008

With lumber from the ship’s stores, the crew and passengers built these crude bunks on the City of Flint for most of the 236 Athenia survivors taken on board. APIMAGES, 3909131314

The Coast Guard cutters Bibb and Campbell were sent by the American government to meet the City of Flint in the mid-Atlantic on 9 September and escort her to Halifax. Survivors with serious injuries and broken limbs were transferred to the cutter Bibb on the morning of 10 September, and fresh food and supplies were also delivered to the City of Flint. APIMAGES, 3909131264

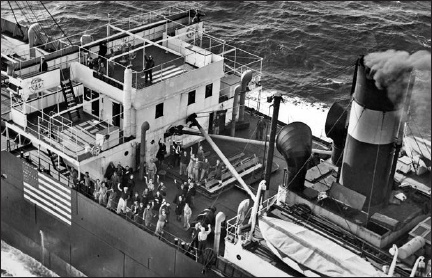

The City of Flint and Athenia survivors photographed from an airplane. Captain Gainard wrote that his passengers feared that they were being bombed by the airplane, although the people on deck are clearly waving to the plane. NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES, JOHN F. ROGERS COLLECTION, 1995-370, NO. 52

Happy Athenia survivors line the rails of the City of Flint as the ship came into Halifax Harbor, where a warm reception awaited them. NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES, JOHN F. ROGERS COLLECTION, 2004-047, NO. 50

Royal Canadian Mounted Police, among the many officials at the dock, assist Athenia survivors off the City of Flint in Halifax Harbor. BRITISH PATHÉ LTD./WPA FILM LIBRARY

The death of ten-year-old Margaret Hayworth on the City of Flint from injuries suffered when the Athenia was torpedoed brought home to Canadians the cruelty of the new war. APIMAGES 3909131330

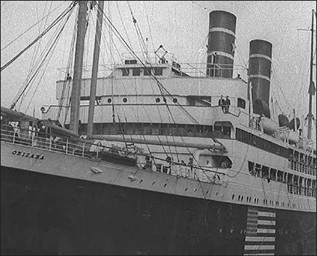

The passenger liner Orizaba was chartered by the U.S. government to take home Athenia survivors stranded in Glasgow and Galway and other Americans in Britain. BRITISH PATHÉ LTD./WPA FILM LIBRARY

Children with new clothes and toys board the Orizaba on 19 September, bound for New York. AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

Survivors boarding the Orizaba in Glasgow BRITISH PATHÉ LTD./WPA FILM LIBRARY

Andrew Allan returned to Canada by way of the Orizaba and New York and is seen here directing a radio play for the CBC in 1945. He subsequently had a distinguished career in radio and television productions for the CBC. His father, Rev. William Allan, was lost when the propeller of the Knute Nelson sliced through lifeboat 5A. CBC ARCHIVES

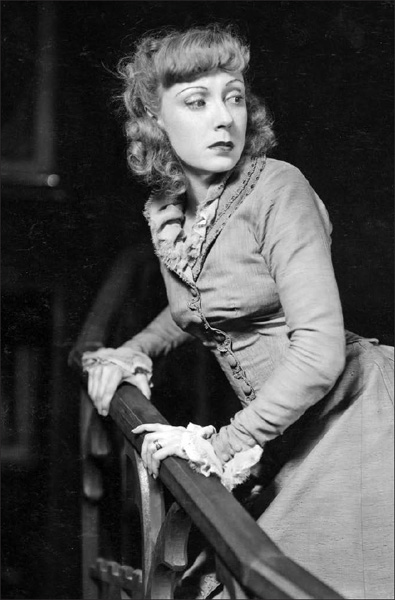

Judith Evelyn, who had been a promising actress in Canada and Britain before her experiences on the Athenia, went on to become very successful both on Broadway and in Hollywood. She is shown here in a scene from the Broadway play Angel Street, in which she played opposite Vincent Price and for which she won the Drama League’s medal in 1942. In the 1950s and early 1960s she appeared regularly in both films and television drama. CULVER PICTURES

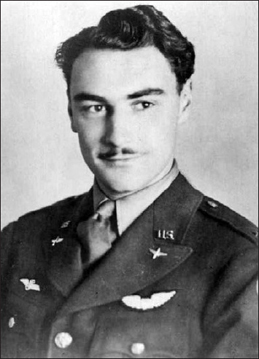

Portrait of Major James A. Goodson in late 1942. Goodson’s original Royal Canadian Air Force wings can be seen over his right breast pocket and his U.S. wings on the left. Goodson served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Eagle Squadron of the Royal Air Force, and the U.S. Army Air Forces. Goodson became a highly decorated World War II Ace, destroying at least thirty German planes before being shot down himself. MELANIE BROOKS

Young James A. Goodson with his mother, Mrs. Gertrude Goodson, about the time of the sinking of the Athenia MELANIE BROOKS

Although baby Nicola was not a celebrity, her father Ernst Lubitsch was one of the most famous film directors of his time. Indeed, the baby’s nurse, Carlina Strohmayer, became something of a celebrity for the care she gave the child during the Athenia crisis. INTERNATIONAL MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHY/CORBISIMAGES

Young Rosemary was reunited in Canada with her parents, David and Barbara Cass-Beggs, in late September 1939. David became a professor of engineering at the University of Toronto and later a power company executive, and Barbara developed expertise in folk music and music for children. Rosemary studied at Oxford and became a psychologist and a writer. ROSEMARY CASS-BEGGS BURSTALL

These arrangements were being made against the backdrop of the international crisis and the outbreak of war in Europe that everyone had feared. The Athenia sailed from Princes Dock in Glasgow just after noon on Friday, 1 September. The Texas college girls gathered on the deck of the City of Flint to wave farewell to their friends as the passenger liner moved slowly down the Clyde. Captain Gainard was in a restaurant in Glasgow when he heard that Germany had invaded Poland. He went to the American consul general’s office and telephoned the ship to have the American flag painted on the side of the vessel so that it could be identified at some distance at sea by a warship or a submarine. The chief officer replied that the men were already at work and that they would also paint the flag on the chartroom roof so that it could be seen from an airplane as well as from a ship. Finally ready for sea, the City of Flint sailed at eleven o’clock on the evening of Friday, 1 September. The new passengers gathered on deck, excited by the ship’s departure, by all the activity on the Clyde, and by seeing the newly built Cunard liner, Queen Elizabeth, at its berth.5

![]()

Sunday, the second full day at sea, passed comfortably enough, although there was a little strain between some of the crew and the passengers. Nevertheless the passengers joined in working with the crew to get the sleeping quarters hosed down and cleaned up in order to be made comfortable. Amherst College student Caleb Davis, the son of the U.S. consul general in Glasgow, Leslie A. Davis, described helping to build some “deck chairs” and benches so that people could take their ease and sun themselves while listening to the radio coming from the chief engineer’s cabin. He also exclaimed that the meals prepared by the steward, Joe Freer, were excellent; the best meals since leaving the United States, one person said. Altogether this voyage on the City of Flint promised to be “one of the pleasantest crossings any of us had.” In the evening after dinner, card games were organized in the chief engineer’s room for most of the passengers and several of the officers. About 9:00 p.m. the captain was handed a slip of paper by the radio operator. This was the distress signal from the Athenia. Captain Gainard was careful not to alarm his new guests that their friends might be in danger. He went immediately to the bridge to consult with his officers and to chart a course to where, given the wind and the currents, the Athenia and her lifeboats would be in about twelve hours’ time. The City of Flint sent the radio message that it was making all speed and would expect to reach the lifeboats at about nine the next morning. Having himself spent a night in a lifeboat in the North Atlantic when the President Lincoln went down in 1918, Captain Gainard had no hesitation about steering the ship directly toward the Athenia’s radio signal at full speed. Caleb Davis thought the engines were working so hard that they sounded as though they “were about to disintegrate any moment.” Because of the possible danger of submarines, the passengers were ordered to put on their lifejackets and to keep their passports in their pockets. All of the ship’s deck lights were turned on and spotlights were directed toward the American flag to eliminate any ambiguity about the ship’s nationality.6

When Captain Gainard left the card game he took with him to the bridge one of the two older women passengers, a schoolteacher who he recognized as being a dependable person. He realized that he was going to need the extraordinary help of both his crew and his passengers in order to be of assistance to an unknown number of survivors from the sinking Athenia. He also concluded that since the Athenia had been sailing to Canada there was no point in bringing the survivors back to Great Britain. The City of Flint, therefore, would proceed across the Atlantic, but it would need still more beds than those that had been improvised for the passengers. Gainard called on the ship’s carpenter and one of the passengers, John Stirling, a former ship’s carpenter from San Francisco, to organize the other male passengers, college students, schoolteachers, and professors, to begin building bunks with bits of lumber on the shelter deck—a space about 40 feet by 40 feet. Crew members joined in when they came off watch, and they all worked together through the night. “They were the best crew of volunteer workers you’d ever see,” Captain Gainard said. “They couldn’t do enough.” Even the Athenia survivors, when they came on board, joined in the task. “I was one of the gang that went straight to work to build bunks for ourselves,” Hugh Swindley wrote. Although it would take several days to complete, the results were a series of bunks in two tiers that would hold six to eight people in each tier. Heavy canvas was stretched over the rough boards and slats were put in place every two feet to define a single space. Two hundred fifty-five primitive, but workable, bunks were eventually put together. Blankets would be in short supply initially, but people would share, use their coats if they had them, and in some cases just cover themselves with bits of canvas or heavy paper.7

The steward, the two cooks, the mess boys, and some of the women passengers began making beef broth, sandwiches, and coffee to give sustenance to the survivors when they came aboard. Captain Gainard organized his passengers to “take the survivors in hand, the men one way, and the women . . . another route.” They were to get the survivors into dry clothes, warmed up, and into the bunks as soon as possible. Dr. Richard L. Jenkins, a physician at the New York Training School for Boys who had been attending the scientific conference in Edinburgh, offered his services. Captain Gainard knew there would be injured and distressed people among the survivors and commented that “a real medical man was like a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.” He was right. The ship’s hospital room was opened up and one of the college girls, Margaret Batts from Fort Worth, Texas, was assigned to work with Dr. Jenkins. The chief officer had the ship’s four lifeboats made ready and swung out over the side and he picked a boat crew of the largest and strongest men from the ship. “There is something encouraging about a six-footer at an oar,” Captain Gainard observed. When dawn broke several of the young women were stationed as lookouts. The City of Flint was in contact with the Southern Cross and several of the other rescue vessels during the night, but at 8:40 a.m. smoke from the Southern Cross was sighted and within minutes the freighter came alongside the steam yacht. On the Southern Cross Montgomery Evans said it seemed to take forever for the freighter to reach the yacht. Survivors now had to decide whether it would be safer to return to Scotland on the Royal Navy destroyers or to transfer to the City of Flint and sail for Halifax. Mrs. Isobel Calder decided that if she and her sister and daughter returned to Scotland they might never get back to Canada until the end of the war. Her young travel companion Ruby Mitchell remembered, “She figured she’d better just continue,” so they prepared for the transfer. Large numbers of survivors could be seen on the decks of the Southern Cross, and empty lifeboats bobbed up and down in the swells nearby. Chief Officer B. L. Jubb took command of the ship’s boat and had it lowered away. Dr. Jenkins with a first aid kit was the first one in the boat and he was joined by Jubb, Cadet Officer Carl Ellis, and seven crewmen.8

![]()

The most seaworthy of the Athenia’s boats had been saved and the first was rowed alongside the City of Flint by Swedish sailors from the yacht. It was filled with “miserable looking” women. Captain Gainard greeted the first person to come up the Jacob’s ladder who ironically was German. She and those who followed her were welcomed by the captain and sent to get dried off and cleaned up—many people being covered in fuel oil as well as wet from seawater. Some people were only partially clad and cold and needed to be warmed up as well. Caleb Davis, who helped people get up from the lifeboats, carried stretchers, and lifted babies and children, described the scene: “they were a mess when they came aboard; all covered with oil, some of them practically undressed and shivering, too weak to stand up and sick all over the place as soon as they set foot on deck.” The college girls were wonderful in comforting the women and children and taking them off to get warmed and be given something to eat. “Mothers and children [were] wailing and crying, but most of them were overcome with joy at the idea of being on an American ship,” Davis noted. Montgomery Evans thought the freighter looked “rather dumpy” and the sides of the black hull enormously high, but he was glad to see the American flag painted on the side. “Staunch Britisher though I am,” confessed Patricia Hale, “I have never been so thrilled and pleased as when I saw the Stars and Stripes painted large on the side of the City of Flint.” Those people who were strong enough climbed up the side of the ship from the boats on a Jacob’s ladder. A sling was devised for others too weak to climb and there were many helping hands, but this was slow and dangerous. One of the City of Flint’s crew concluded that it would be safer, faster, and less frightening to be brought up from the lifeboats with a cargo net hoisted by the one of the ship’s winches. This worked so well with the stretcher cases and with the weak that it was eventually used to bring the remaining survivors on board. Through all of these efforts an anxious vigil was maintained for friends of the college girls who might be among the survivors on the Southern Cross. Even Captain Gainard recognized Anne Baker from Houston waving from one of the lifeboats as it came alongside, and Mary Underwood from Athens, Texas, followed shortly. By about four o’clock in the afternoon the boats from the City of Flint and the Southern Cross had made twenty trips ferrying people across to the freighter and the last of the Athenia survivors were taken off the Swedish yacht.9

![]()

The City of Flint now had 236 Athenia survivors, in addition to the twenty-nine passengers picked up in Glasgow. Captain Gainard observed dryly that a week before his freighter had facilities for no passengers at all. It was fortunate that the captain had ordered so many provisions in Glasgow when he learned he would have some passengers, but even that was not enough. Luckily, a Norwegian lumber ship Alida Gortham, passing the City of Flint while the Athenia survivors were being taken on board, offered whatever help it could give. Captain Gainard asked for blankets, clothing, and food, and they were quickly transferred. The Norwegian ship had lots of potatoes and evaporated and condensed milk, items that were particularly valuable with all of the babies and children on the City of Flint. Indeed the cooking and serving of meals became one of the first problems to be dealt with. A “Little Cabinet” was made up of the two professors, Plough and Child; Chief Officer Jubb; and the steward, Joe Freer, and they organized the meal schedule—there would be three meals a day and eight sittings. Cereal, porridge, scrambled eggs, bacon, and sausage were served for breakfast; soup with bread and jam for lunch; meat, two vegetables, and a small dessert for dinner; and children were served fruit or tomato juice in the afternoon. Young Scotty Gillespie ate so many oranges he was sure they were part of the ship’s cargo and Rosemary Cass-Beggs thought the condensed milk tasted very strange. There were two mess rooms, one held thirty and the other ten. The crew’s dining saloon was larger and was across from the galley. Alexander Hamilton Warner, from Nowata, Oklahoma, was put in charge of the mess rooms and managed the serving of food and washing of dishes. The ship’s crew would eat first and the officers and college girls would eat last. Everyone had ten minutes to eat and would take out their own dishes, which would be washed immediately and given to another person. Even with this organization the cooking, eating, and dishwashing went on almost all day. Patricia Hale and her friend Margaret Patch volunteered to do dishes—given the water shortage it was a practical way to get their hands clean. The college students took food to those who were injured or too sick to get out of their bunks. They also saw to it that the children drank their fruit juice at least once a day and the children loved it. George Cree, a baker from Albany, New York, who was one of the passengers from Glasgow, offered to relieve the second cook who had been doing all of the baking. Cree baked excellent bread and also made cakes and treats that lifted everyone’s spirits.10

The Reverend Dr. G.P. Woollcombe thought it was really quite amazing that this freighter without normal passenger facilities was actually able to house and feed almost three hundred people for ten days. Although young Ruby Mitchell was sure she slept for as much as twenty-four or forty-eight hours, she remembered the bunks as pretty crude. “We were sort of sleeping, you know, together,” in the rows of bunks. “You had to, sort of, crawl out” of the bunks to get into a large aisle. The rows of bunks were quickly given names, such as “Times Square” or “Fifth Avenue” or “Montreal” or “Quebec,” depending on who occupied them. The sleeping facilities and toilets (of which there were only three) needed to be monitored and cleaned and people volunteered to look after those matters. Bedding had to be aired and was strung up on lines on deck when the weather permitted. A “Captain’s Inspection” was held every day and both Dr. Jenkins and Captain Gainard checked on how people were doing. Clothing was still in short supply for people who had lost everything. The college girls in particular gave up the new clothes they had bought in their travels across Europe, but the crew gave out clothing also. Captain Gainard, who was enormously proud of his crew, said that three of his sailors took turns wearing one pair of shoes. Chief Officer Jubb showed people how to make sandals out of rope and canvas. Three-year-old Rosemary Cass-Beggs was carried about the ship until some shoes were made for her. There was not enough water for showers, but an engineer gave John Coullie a bucket of hot seawater with which he washed the oil out his wife’s hair and his own. Some of the men also borrowed razors and were able to shave. People could wash their clothes with hot seawater and dry them on the grating in the engine room, but many had to wear the same clothes until they got to Halifax.11

The first several days on board the City of Flint for the Athenia survivors who had transferred from the Southern Cross were hectic and unsettling. Many were traumatized by the whole experience and some sick with worry about missing family members. The deteriorating weather conditions raised peoples’ anxieties even further. “The first night on board [the City of Flint] I thought I’d die,” said Dorothy Dean, who remembered a terrible storm. Not only were the ship’s movements violent but there were also loud noises from both the deck and cargo hold when the waves hit the ship. Caleb Davis told his parents when heavy seas pounded “that little tub,” the ship did in fact “jump around.” Reverend Woollcombe commented, “Above us we heard from time to time loud bangs, and so many of us suddenly roused from our sleep by the unusual noise,” and remembered the “Bang” when the Athenia was torpedoed. Some loose cargo rolled around, water poured through ventilators and one of the hatches, and at one point the makeshift lighting system went out. “Women called out in temporary terror, and children began to scream.” Dorothy Dean said, “It was awful. . . . No one slept.” Over the next several days the weather gradually moderated. But sleep remained difficult for many people because of the heat. The beds were directly over the engine room. Captain Gainard realized that it would be better if those among the survivors who were reasonably fit were kept busy, so almost everyone was given tasks, and it worked. The children were encouraged to run around and play games on deck—“I Spy” and “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral” were favorites. Adults helped to clean, wash dishes, stand watch, and serve as lookouts. Even a ship’s newspaper was created. Dorothy Dean and several of the young girls listened to the radio, took notes or shorthand, and typed up the news they had heard. Captain Gainard later said of Helen Crosby, a Swarthmore College student who had paid for her passage, “She worked until she had blisters on her hands. We had to tie her down to make her rest.”12

One of the first important tasks to be carried out was to put together a list of all of the names of the Athenia survivors on board the City of Flint. The fact that survivors had been brought into Glasgow and Galway on 5 September, together with the problem of separating families on a “women and children first” basis while getting into lifeboats, meant that there was a serious difficulty for officials in England and Ireland in attempting to compile an accurate list of those who had survived and those who had not. This was compounded by the mystery of who was among the survivors taken on board the City of Flint. As soon as everyone was on board and looked after, Captain Gainard had the names of his survivors taken down and radioed to the U.S. Maritime Commission offices in New York and London. These names began to complete the list of who was saved and who was lost. One puzzle was that of a baby girl without her parents. Those looking after her could not quite make out what she called herself. It sounded like she said “Rose Marie Caspicks,” possibly from Oxford. Her desperate parents in Glasgow could figure it out, however: she was Rosemary Cass-Beggs, and they were the only family on board the Athenia from Oxford. She had been carefully looked after in the lifeboat, on the Southern Cross, and now on the City of Flint by Mrs. Winifred Davidson of Winnipeg. The Cass-Beggs cabled friends in Canada to meet the City of Flint and baby Rosemary in Halifax.13

The injured and sick were looked after in the ship’s small hospital and then lodged in the officers’ cabins. Dr. Jenkins had plenty of broken limbs and bruises to look after and was very much appreciated. However, one of the Athenia survivors was Dr. Lulu Sweigard from the physical education department at New York University, with some medical experience. After she was cleaned up, given some clothes and a bit of rest, she became Dr. Jenkins’ able and forceful assistant. Dr. Jenkins said of her that “on one occasion she worked for over thirty-six hours without rest” and that she was indispensable to the organization of assistance to people on the ship. She was joined by several other Athenia survivors, Mina McKellar and Mrs. E. A. Martineau, both graduate nurses, and by Hugh Swindley, who felt he could relieve the doctor of some of the menial tasks. One little girl, ten-year-old Margaret Hayworth from Hamilton, Ontario, had a serious cut on her head but nothing obviously wrong with her, but as she lay motionless beside her mother in the wheelhouse Captain Gainard became concerned. He called the doctor, and the child was found to have suffered a severe brain concussion as a result of the explosion on the Athenia and she developed a fever due to the swelling of her brain. The following day her complexion had changed and she looked worse. Dr. Jenkins found that her temperature had risen to 105 degrees. She and her mother were moved to the hospital and the doctor concluded that he would have to give her a spinal tap to reduce the temperature. Dr. Jenkins, Dr. Sweigard, Professor Childs, the chief officer, and the steward all worked to devise a suitable needle to perform the operation. Eventually they came up with the right tool, which was sterilized and worked in the operation. Margaret Hayworth’s fever was reduced, but she was still in danger. Because of the concern for the child, when the Moore-McCormick Line passenger ship SS Scanpenn, sailing from New York to Sweden and the Baltic, radioed that she was nearby and would give any help needed, the City of Flint answered back that they could use some medical assistance and food supplies. The two ships altered course and, despite being enclosed in fog, sought each other out and made a successful rendezvous on the evening of Thursday, 7 September. The doctor from the Scanpenn came aboard bringing very helpful medical supplies and consulted with Dr. Jenkins. While he agreed that Dr. Jenkins had done all the correct things they realized that Margaret was very sick. Prayers were said for the little girl at the nightly services. Indeed, although the child seemed to improve, and even talked, on the evening of 9 September she began to decline and early next morning Margaret Hayworth died. Her mother, Mrs. Georgina Hayworth, was understandably distraught and particularly upset at the thought of the child being buried at sea. Dr. Jenkins and the chief officer therefore embalmed the body as best they could by wrapping it in layers of sheets and spices of clove and cinnamon.14 Margaret Hayworth was brought back to Hamilton where she was given a very public funeral.

The Scanpenn also sent some fresh vegetables, candy, cigarettes, and magazines, so the ship’s stores were helpfully replenished. Captain Gainard was given a parcel labeled “for the little ones, in care of the Master of the City of Flint.” This package was filled with toys and candy that a woman on the Scanpenn had been taking to her grandchildren in Sweden. She decided that the children on the City of Flint were in greater need. Captain Gainard radioed back to the Scanpenn his many thanks to “The Countess of Sweden” for her noble gesture. These treats provided the excuse to try to bring some cheering up to both the children and the adult survivors of this great sea disaster. One problem was that there was not enough candy for all of the children. The volunteer baker, George Cree, made delicious cakes and cookies that more than compensated for the shortfall. A “children’s party” was held at three o’clock the next day. “The children flocked to it,” Patricia Hale remembered, “joyous at the sight of the cake.” As the ship proceeded west across the Atlantic other entertainments were arranged also: talent contests, limerick readings, and “fashion” shows, featuring the outlandish, makeshift apparel the survivors were wearing. Ruby Mitchell and her friend Margaret Calder got a huge laugh with their costumes—Ruby with her man’s shirt from the Southern Cross together with a lady’s sunsuit, and Margaret with a sailor’s top and a towel wrapped around her as a skirt. Dr. Jenkins, several members of the crew, and one or two children became outstanding performers. Little Rosemary Cass-Beggs won a prize singing “Daisy, Daisy.” The ultimate festivity was the “Captain’s Dance” the last evening. The “Entertainment Committee” was kept very busy.15

![]()

Captain Gainard had decided when he picked up the Athenia survivors that he would not return them to Britain but would carry them across the Atlantic where they were headed. The City of Flint was bound for New York Harbor, but a North American port several days closer was Halifax, Nova Scotia. So Halifax became the immediate destination. The public shock of the sinking of the passenger liner and further anxiety about the safety of the survivors while on board the City of Flint prompted the U.S. government to take some protective action. Two U.S. Coast Guard cutters were sent out to meet the City of Flint and to escort her across the Atlantic and into Halifax. The USCGC George M. Bibb and George W. Campbell joined the City of Flint during the night of 9 September. Captain Gainard turned his searchlight straight up into the clouds, which could be seen for miles, and the cutters responded with their lights and then took up stations on either side of the City of Flint. At 8:15 the following morning the three ships hove to, and the cutters sent boats over to the City of Flint with medical officers, men, supplies, and fresh food. Ten of the seriously injured survivors, including two with broken arms, one with a broken ankle, and one with a cracked rib, were put in metal stretchers and placed again into the cargo net and lowered over the side into the Coast Guard boats and taken to the cutters, along with the wife of one of the injured, where they would have more room and more complete medical service.16 For the most part, however, the Coast Guard doctors approved of what had been done for the survivors and gave the City of Flint a good inspection. They also brought additional blankets and fresh vegetables and meat and, most welcomed by the survivors, toothbrushes and combs. The college girls received lots of good-natured teasing when they discovered lipstick and makeup just as the young Coast Guard officers arrived on the ship—they were subsequently known as the “Killer Dillers.” The two cutters escorted the City of Flint for several days, and their gleaming white presence was greeted with emotion and was a source of reassurance to many of the Athenia survivors.

As the ships approached the Nova Scotia coast, a plane with newspaper photographers buzzed the vessel to get the first pictures of the ship. This so startled and upset many of the Athenia survivors, who feared that they were being bombed, that a request was made for no special ceremonies or celebrations when the City of Flint arrived in Halifax. However, the photographs showed many people on deck waving cheerfully to the airplane. Special permission was granted for the Coast Guard cutters to enter Halifax, and they left their position with the City of Flint early on the morning of 13 September to enter the harbor first. Captain Gainard had radioed the Halifax Harbor authorities forty-eight hours earlier that he had 265 passengers of Canadian, British, American, and other citizenship, and no sick, although of course many were without passports, visas, or entry permits. The ship’s papers were not in order, but the emergency overruled protocol. Within minutes he was granted “free pratique,” or permission to land his passengers, thanks in part to the careful preparations by the American consul general in Halifax, Clinton E. MacEachran. When the ship approached the harbor entrance the pilot came on board and took the City of Flint into Halifax.17 The first of the Athenia survivors were home.

Tugboats brought the City of Flint into Pier 21 at the Ocean Terminal in Halifax at 10:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 13 September. The two Coast Guard cutters Bibb and Campbell anchored in the harbor. Although Captain Gainard had requested that there be no actual celebrations, a very large number of people had turned out to see the ship and welcome the survivors ashore. The crowd gave three cheers for the survivors and sang “Oh, Canada” as the ship was moored to the pier. The first to board the City of Flint was the premier of Nova Scotia, Angus L. Macdonald. Forty newspapermen and press photographers went on the ship also. Present at the dock were provincial minister of health, Dr. F. R. Davis, the mayor of Halifax, Walter Mitchell, and officials from Canadian immigration, the Canadian Red Cross, the Canadian navy, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and the Boy Scouts, as well as Consul General MacEachran, representatives from the U.S. Maritime Commission, the ship’s agent, the American Red Cross, and the Cunard White Star Line. When praised by reporters as a hero, Captain Gainard shrugged off the compliment with the gruff statement: “There is no such thing as a hero. You’re either a man or a bum.” Cpt. Alan Reid represented the Maritime Commission and told Captain Gainard, “That was a swell job skipper.” He passed on a letter from Adm. Emory S. Land, head of the commission, praising the efforts of Captain Gainard and his crew “for your outstanding service to humanity, according to the finest traditions of the sea.” This was a sentiment echoed by many others from the ship. Dr. Lulu Sweigard noted that Captain Gainard and his crew had worked very hard and made great sacrifices for Athenia survivors. “He seemed never to snatch any rest,” she concluded. Dr. Jenkins said that if he ever were to have a similar experience, “I should want it to be with Captain Gainard.” The Montreal Gazette commented that “if King George could bestow the Victoria Cross on a ship, it would go to the City of Flint in the opinion of the survivors of the Athenia.” Captain Gainard responded to all of this praise by saying, “I’ve got the finest crew a man ever wished to sail with. I ran the ship. They did the rest. God bless every one of them.”18

Elaborate preparations had been made by Canadian Immigration and representatives of the Cunard White Star Lines, acting on behalf of the Donaldson Atlantic Lines. A number of doctors were in attendance, as well as registered nurses and volunteer nurses from the Red Cross. The U.S. consul was taken by a police boat out to the USCGC Bibb and Campbell to make arrangements for several of the seriously injured and sick to be brought into hospital in Halifax and the Americans to be taken to New London, Connecticut. Four large rooms had been reserved in the terminal building, two for men and two for women and a nursery for children, and adjacent were washrooms, bathing facilities, and dressing rooms. Ruby Mitchell delighted in her first real bath since the sinking and also exchanged her man’s shirt for a dress and sweater from T. Eaton’s & Company. The Canadian Red Cross had clothing available for those who were dressed in borrowed or makeshift gear. Close by there were also reception rooms where the survivors could be reunited with family and friends and where generous amounts of food were served. Boy Scouts stood at the bottom of the gangway to direct survivors where they wanted to go. Canadian and U.S. Immigration officials set up tables in the terminal where people could present themselves, after meeting with family or having a bath, to deal with the paperwork of arrival, whether they had the proper documents or not. In addition to assisting with the paperwork, these officials were also able to assist survivors in making telephone calls or sending telegrams to family members across Canada and the United States. By the end of the afternoon all of the people who had come off the City of Flint had been processed, including at least 109 American citizens. The Stewarts booked into the Lord Nelson Hotel in Halifax. Douglas had not had a change of clothes since 3 September, and the bath in the hotel was “the most welcome one we had ever had.” Their two sons drove down from Montreal, bringing fresh clothes and a joyful reunion. The Cunard White Star Line had arranged, for those disembarking in Halifax, that a special Canadian National Railway train of sixteen sleeping and dining cars be available to leave for Montreal at 6:15 in the evening. The infant Nicola Lubitsch and nurse Carlina Strohmayer were met by the glamorous actress who had traveled from Hollywood, Sari Maritza, the wife of Sam Katz, the MGM executive that had alerted Ernst Lubitsch that his daughter was on the Athenia. Nicola’s mother, Vivian Gayle Lubitsch, was still in England hoping to get passage back to the United States. Mrs. Davidson and Rosemary Cass-Beggs were met in Halifax and assisted onto the train, Rosemary being given a Panda bear that replaced the one lost on the Athenia. In Montreal friends of the Cass-Beggs, Dr. James and Caroline Gibson, met them at the train station. “She was smiling brightly and sweetly,” Caroline Gibson said, “a precious little mite in all that mob.” “Auntie” Davidson, who had looked after Rosemary for almost two weeks, found it hard to say goodbye: “I had to kiss her and walk away quickly.”19

From Montreal people could make their way on to other parts of Canada or the United States. The husbands of Isobel Calder and Christina Horgan came to Montreal to meet them, but Ruby Mitchell’s mother was at the train station in Toronto to greet her. When the train came in, young Ruby was the first person let off the carriage. There on the platform was her mother. “She just hugged me and hugged me and hugged me,” Ruby remembered years later, “and I guess we both cried.” Ruby’s Toronto relatives were there too and they all went home for breakfast, although Ruby concluded that one of them must have made the breakfast because her mother would not let go of her. Many Americans came into New York by train at the Pennsylvania Station on Friday, 15 September. A chartered Canadian Colonial Airways flight into Newark, New Jersey, brought four-year-old Gale McKenzie and her mother; young Erika Hubscher; Mr. and Mrs. Alex Craig; Ernest Zirkl; and Charles Foster back to the United States to be met by the acting mayor of New York City. Eastern Airlines sent a charter flight to Halifax to carry newspaper reporters to meet the City of Flint and to bring back to Newark five of the Texas college girls, Mary Catherine Underwood, Constance Bridge, Anne Baker, Dorothy Fouts, and Betsy Brown. Consul General MacEachran was pleased to say that he had heard no word of dissatisfaction about these facilities and arrangements from any of the Athenia survivors. Indeed, the people coming off the City of Flint were relieved and grateful for everything that had been done for them. The ship carried on with her twenty-six remaining passengers and survivors and docked at Hoboken, New Jersey, on Saturday, 16 September. Among the Athenia survivors were Janet Olson of Honolulu, Dr. Lulu Sweigard of New York, Kay Schurr of Brooklyn, Gerda Sachs of Bavaria, Germany, and Mrs. Maria Kurilic and her five-year-old daughter from Czechoslovakia. Mrs. Kurilic was met by her husband, William, who had emigrated to the United States several years earlier. What should have been a joyous reunion was tempered by the anxiety that their son Jan, a boy of ten, was still listed among the missing.20