Lily at Lissadell is a mixture of fact and fiction, so I thought I’d write these notes so you can see who really existed, and who came from my (over-active) imagination.

First, I’d like to mention my grandmothers Julianne and Mary Anne – who were very real and very much alive in 1913! Julianne left school at the age of twelve, and went to work as a maid in a house in Cork city. The story about Lily and the Christmas present of winter boots is based on something that happened to Julianne. Mary Anne also left school at a very young age. When she was fourteen she travelled to New York with her sister, looking for work. She found employment as a maid in a large house in New York State. I still have the dinner service her employers gave her when she left work years later to marry my grandfather. (Married women hardly ever worked back then.) The cup on the back cover of this book is from that tea set, while the one on the front cover is from Julianne’s wedding tea set.

I regret that I didn’t ask my grandmothers enough questions while they were alive, so if it’s not too late, grab your granny (or grandad) and ask them to tell you about their youth.

The House

Lissadell is a real house in County Sligo. It was built in the 1830s for Robert Gore-Booth, and remained in this family until 2003. Over the years, many interesting and famous people have visited, including the poet W.B. Yeats. I visited in the spring of 2019, during my research for this book. It’s a beautiful place and if you go there you can see many things mentioned in the book, like the servants’ bedrooms, the grand staircase, the porte cochere and the stuffed bear that frightened Lily. You can also see the window where the young Constance Markievicz scratched her name.

The People

Lily and Nellie did not really exist (sorry!) I did a lot of research though, and the lives they lived and the jobs they did are as accurate as I could make them. Many of the other servants were made up too, but quite a few of the people in this book were real. I had a lot of fun researching their stories and putting words in their mouths.

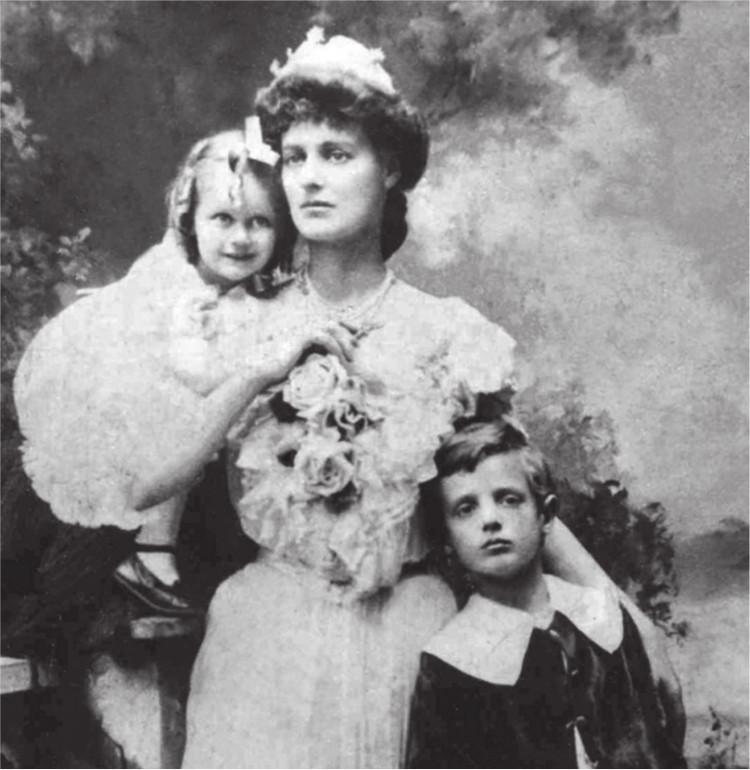

Countess Constance Markievicz

Constance was born in 1868, the eldest of five children. Her sister Eva was her best friend. Constance loved the outdoor life. She enjoyed sailing and was a skilled horsewoman and hunter. She was an accomplished artist – once she did a sketch of a servant in Lissadell. She studied art in London and Paris, where she met her husband Count Markievicz. Initially, she hoped to win votes for women, but then she decided that freedom for Ireland should happen first, saying, ‘There can be no free women in an enslaved nation.’

During the 1913 Lockout, she worked hard to establish a soup kitchen to feed poor families. She fought during the 1916 Easter rising and was sentenced to death, but because she was a woman, she was sent to prison instead. She was freed in 1917, and in 1918 she was the first woman ever elected to the British House of Commons. In 1919 she became the Minister for Labour in the Dáil – only the second female minister in the world!

Constance was always generous, and gave most of her wealth to poor people in Dublin. The year before she died she often drove to the country to collect bags of turf, which she gave to families who would otherwise not have been able to heat their homes. When Constance died at the age of fifty-nine, thousands of people came to her funeral.

Maeve de Markievicz

Maeve was Countess Markievicz’s only child. She was born in Lissadell House in 1901. Her parents left her in the care of her grandmother, Georgina, for most of her childhood, except for a short period when she lived with them in Dublin, along with her half brother Stanislaus. When she was six she returned to Sligo, and never lived with her parents again. As her Lissadell cousins were much younger, she spent a lot of time with the servants. She liked working in the garden with her Uncle Josslyn, and regularly tried to paint portraits of family members. At the age of sixteen she was sent to boarding school in England, where she became an accomplished violinist. After that she spent little time in Ireland. Some years passed during which she never once saw her mother. When she was twenty, they arranged to meet, but failed to recognise each other, and had to be introduced. (No Instagram or WhatsApp for them!) Maeve trained as a landscape gardener, and also took up painting again towards the end of her life. Maeve died in England in 1962.

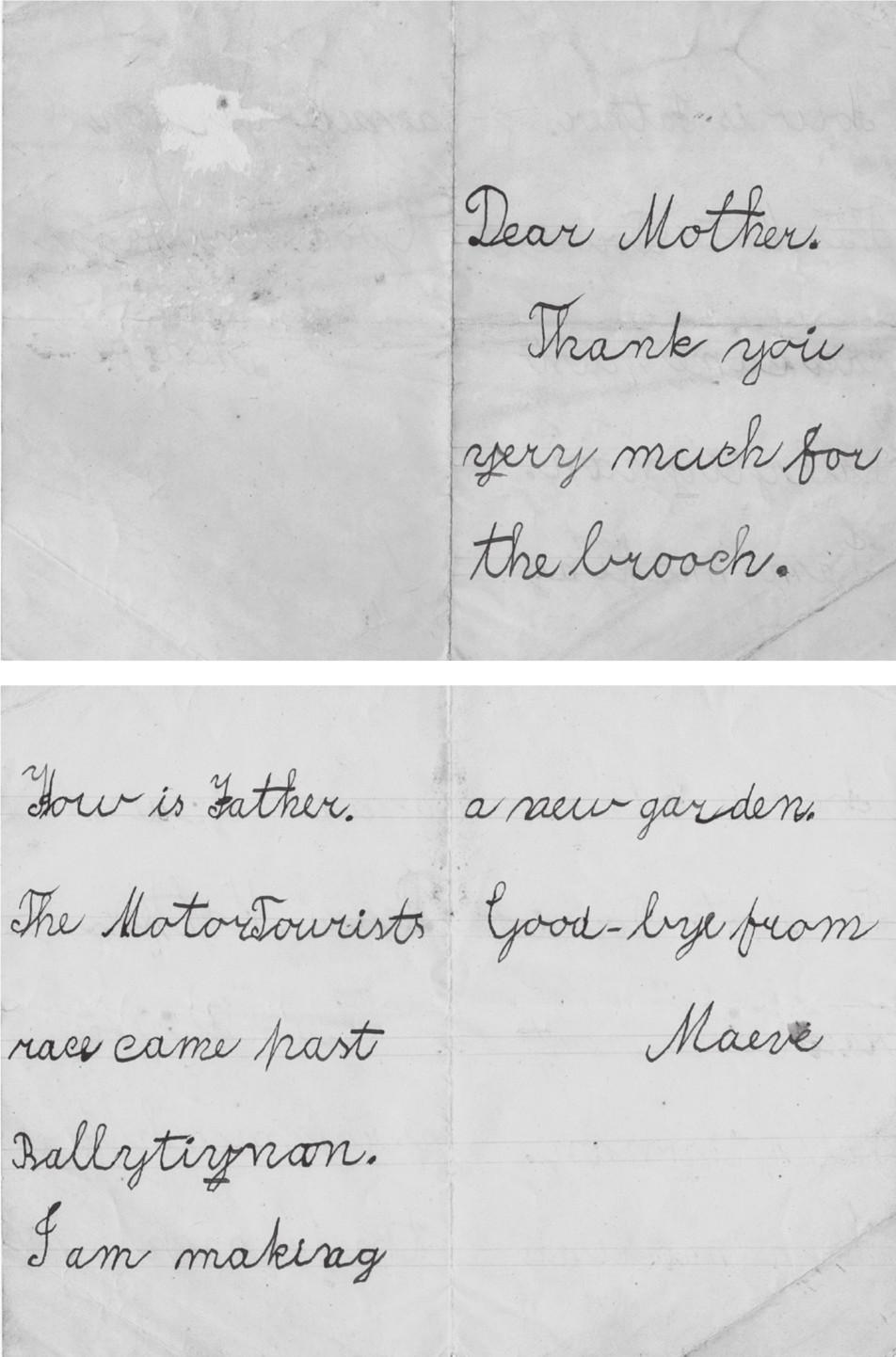

Maeve wrote this letter to her mother in 1906, when she was five years old.

Sir Josslyn Gore-Booth

Sir Josslyn was Maeve’s uncle, and the owner of Lissadell House. His sister, Constance, was older than him, but back then houses and titles went to boys instead of girls! (This wasn’t his fault so we shouldn’t hold it against him.) He was a good landlord, and worked hard to create employment for local people. He was very interested in horticulture, and developed a number of new daffodil varieties. He was a bit embarrassed by his sister Constance, but when she was sentenced to death, he did all he could to save her.

Butler Kilgallon

Thomas Kilgallon worked for the Gore-Booth family for sixty years, starting when he was ten years old. Count Markievicz did a painting of him on a pillar in the dining room in Lissadell House – it’s still there today.

Books about Lily’s Time

Since I wasn’t alive in 1913(!) I had to read lots of books to find out what Lily’s life would have been like. When I first started to think about this book, I knew I’d be writing about a fictional housemaid, but when I discovered Maeve de Markievicz: Daughter of Constance by Clive Scoular, my story almost began to write itself. I hadn’t known that Countess Markievicz had a daughter, and I was very keen to learn more about her and her life.

These are the other books that I read:

Blazing a Trail by Sarah Webb and Lauren O’Neill

Countess Markievicz: An Adventurous Life by Ann Carroll

Constance Markievicz by Anne Haverty

The Gore-Booths of Lissadell by Dermot James

Revolutionary Lives by Lauren Arrington

I also found lots of useful information on the website www.lissadellhouse.com

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Michael O’Brien who first suggested that I write about the Gore-Booth family and Lissadell House. Big thanks to the current owners of Lissadell House, Edward Walsh and Constance Cassidy, who generously allowed me to visit their home, and shared their huge knowledge of the house and the Gore-Booth family. Thanks to my friend, Sarah Webb, who listened patiently while I worked out early plot details and struggled with a title. Thanks as always to the team at O’Brien Press, who work so hard to bring my books into the world. Special mention has to go to super-editor Helen Carr. Thanks to Rachel Corcoran for another beautiful cover illustration. Thanks to my mum, who shared stories of her mum’s early life as a housemaid. Thanks to Dan, and my now scattered children for their ongoing love and support.