1

The Road to Virtual Distance

In 2002, anecdotal evidence was mounting that people were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with their work and employers. Ironically, the news came at the same time that the most advanced and easily accessible communication and collaboration tools were being adopted. This is still true today. According to The Conference Board, while the average numbers on job satisfaction are moving higher, a closer look reveals that only 38% of employees are satisfied with communication channels. Only 37.5% are satisfied with their potential for future growth, 37% with recognition and acknowledgment, and 36.1% with workload.1

So 15 years after we started this work, a large portion of the workforce is still dissatisfied with collaboration conduits that form the basis of other essential aspects of work, even though the technology seems light years ahead of what it was then. However, it's not surprising when you consider the rise of Virtual Distance.

It's critical to keep this in mind. Since we uncovered Virtual Distance, we've known that although communication technologies are the enabler of virtual work, they are not the main issue when it comes to a lack of job satisfaction. Rather, it's the human-based interactions measured within and between the Virtual Distance factors as a whole that are the main causes of workplace dysfunction. And this has been true for quite some time. In fact, when we look back, Virtual Distance emerged even before smartphones and tablets ignited the meteoric rise of what we now call virtual work.

A BRIEF LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY

When we started to research the challenges of virtual work the iPad and the iPhone didn't even exist and the iPod had been on the market for less than a year. Blackberry phones and personal digital assistants (PDAs), often thought of as the first “smart” mainstream mobile devices, didn't show up until 2002, with the number of users peaking at 84 million a little over ten years later. However, market share dropped precipitously after the operating systems iOS and Android eclipsed all rivals.

As we said in the Preface, despite continued developments in smart digital devices (SDDs), Virtual Distance has become a worldwide phenomenon and its impact on outcomes in all walks of life is gaining strength and power.

In the early years of the new millennium the prevailing belief was that the benefits of information and communication technology (ICT), as it was called then, were unlimited. It was widely reported, for example, that information technology (IT) accounted for a large increase in productivity.

As seen in Figure 1.1, between the years 1990–2000 labor productivity growth averaged 2.2%, then rose to 2.7% between 2000–2007. Many claimed that information technology accounted for much of that gain. However, from 2007 through 2018, from the time the iPhone came to market through present day, labor productivity has dropped to 1.3%, the lowest level since the 1970s. Recall in the Preface that we saw a similar trend in productivity within the CPG Inc. case study.

FIGURE 1.1 Productivity change in the nonfarm business sector, 1947–2018.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/lpc/prodybar.htm)

It's clear then that technology advances alone don't explain what's going on in the workforce. For that we need to understand the rise of Virtual Distance.

RISE OF VIRTUAL DISTANCE

The advent of the internet and digital communication led many to believe that this new world heralded a seamless expansion of global interconnectedness in the workplace. An example is Thomas L. Friedman's The World Is Flat. What we were seeing in our research, however, was something entirely different – reports of increasingly dysfunctional behavior. So we began looking into what prior research had to say.

We quickly realized it wasn't going to be a straightforward pursuit. Our initial inquiries turned up many fields of work that should have been informed by one another but were instead disjointed and even contradictory. For example, in the IT academic literature we found the usual terms “computer mediated communications” (CMC), “computer supported collaborative work” (CSCW), “group decision support systems” (GDSS), and other common categories that either defined or were directly related to virtual work. On the other hand, management literature contextualized virtual work mostly in different terms, mainly “virtual teams,” but did not tie back to lessons learned in IT research.

What we found then, and still see today, is a range of studies focused on the same questions spread out across many different fields. However, even though they look at the same issues, many don't take advantage of other findings. Therefore, possible connections between them or follow-on “aha” moments are missed. Additionally, since most of the studies were based on student samples their usefulness to practitioners was also limited.

So we began asking questions formed from our experience as executives in the corporate world. For the first year and a half we interviewed dozens of people: C-level executives, managers, and individual contributors who had experience with virtual teams. They came from a wide range of industries including financial services, pharmaceuticals, management consulting, telecommunications, and consumer goods. We focused on three key questions.

1. What did leaders consider virtual work?

This seemed a fundamentally important question. Early on it was easy to see that there was no common understanding or definition of virtual work and it included everything from telecommuting to outsourcing. And this is still true: the term means different things to different people, and many other terms like remote work are used interchangeably when in fact each “label” is likely pointing to related but different ideas. And, as is typically true, when we don't operate with a common language or sense-making framework it's hard to see what the real issues actually are or what's causing what.

For example, when asked, “What do you consider to be virtual work?” one manager said,

Well, for us, virtual work means that we have a lot of outsourcing relationships. And I can tell you that many of them are not working.

But as we pursued these conversations further, leaders often came to the conclusion that virtual workers included anyone connected to the company and each other through a laptop or other mobile device:

I guess you could say that the entire company is made up of virtual workers, even though we have a policy that mandates everyone come into the office. Many people “talk” to each other using only email or IM (instant messaging), even if they physically sit in the office next door.

2. How was management affected by working with virtual teams?

The answer to this question invariably reflected increasing challenges. For example, one executive from a global financial services company told us,

I've thought about this a lot. I'm not sure how to assess if I trust someone in a virtual environment. So I am constantly worrying about where my team is on any given project. I am trying to use old markers to evaluate virtual workers, and this does not work.

Another manager, from a major pharmaceutical company, said,

Since I don't have direct responsibility for some of the people I manage, in addition to the fact that I rarely if ever meet them, it's very hard for me to give an accurate assessment of their performance. This is a huge challenge.

3. What were the most important organizational and strategic implications resulting from virtual work?

People paused and thought about this one for a while because it was difficult to know where to start. Many thought selecting the right business model was most difficult, as typified by this response from a telecommunications executive:

Hierarchy becomes obsolescent in this environment. It used to be that you could delegate work down through the organization. But how do you coordinate and delegate to people you don't have captive, those who work in virtual environments over whom you have very little control, if any?

Another key issue was raised by the CIO at a major bank:

Some of the technologies we use (to get the work done) are so esoteric that above a certain level in this organization, senior executives have no idea what we are doing. So you are entirely on your own based on the principles that, in general, save the company money, get the job done, and try to promote cooperation with colleagues. This is a global corporation with over 100,000 employees. We couldn't possibly understand what every person is doing.

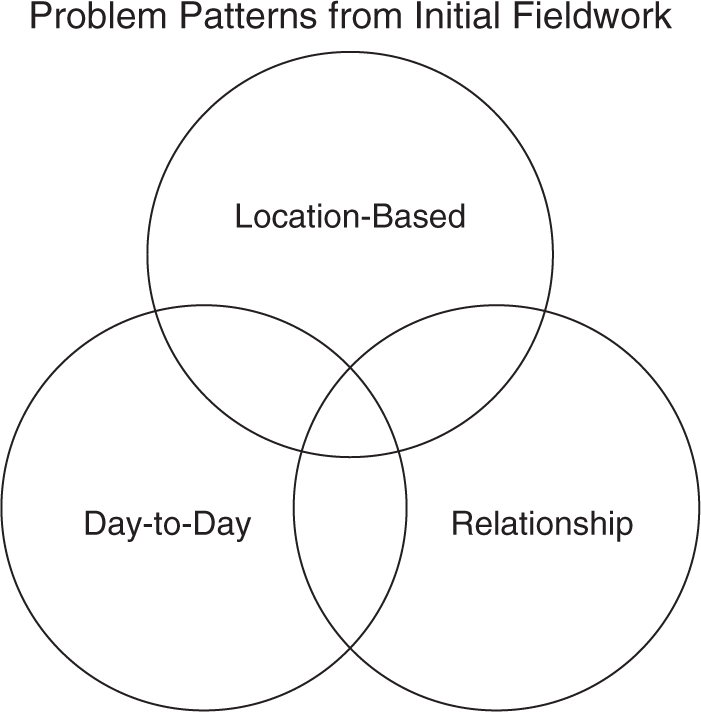

Through these interviews vivid patterns emerged and we categorized them into three groups, as shown in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2 Problem patterns from initial fieldwork.

- Location-based challenges were those described as communication breakdowns between far-flung workers who may or may not ever meet.

- Day-to-day issues included things like frequent miscommunications, too much multitasking, and technology failures that halted momentum in everyday meetings

- Relationship-based problems were those aspects characterized by a felt sense of disconnection at a personal level.

As we reflected on these areas it became apparent that each of them represented a kind of distance. The issues related to location were clearly tied to fixed distances like time, space, and one's organizational affiliation as compared to others. We called these Physical Distance.

The daily trials and tribulations that constantly frustrated people, like having to respond to too much email and a lack of shared context, created regular and repeating psychological distance. We called this Operational Distance because the form it took could change from one day to the next.

The relationship divides grew out of more deeply rooted intuitive disconnects stemming from cracks in cultural values and other social dynamics that prevented people from developing an emotional feeling of closeness. We called this Affinity Distance.

We also found that one group of issues affected many others and showed up in different combinations that varied between companies and situations. So it was important not to fall into the trap of trying to pull them apart and look at them in isolation as a way to explain things like growing distrust and a lack of goal and role clarity. Based on this early fieldwork it was clear the problems were closely connected and when combined formed the new phenomenon, Virtual Distance. Figure 1.3 represents an overview of the Virtual Distance Model.

FIGURE 1.3 The Virtual Distance Model overview.

However, we didn't stop there because identifying the people problems alone didn't tell us about the nature or extent to which Virtual Distance was having an impact on business outcomes, like innovation and financials. Our goal was to develop a method that would directly point us toward actionable solutions. This led to the development of the Virtual Distance Index (VDI), a rigorously tested and validated measure of Virtual Distance that could be quantitatively compared against performance to see what, if any, effect it was having.

Initially, we collected several hundred cases across a wide set of vertical segments, internal functions, and different kinds of project teams. As you will recall from the Introduction, in this updated edition we report on a much bigger data set built over time: 1400 studies, 55 countries, more than three dozen industries, and people representing the most senior to the most junior employees.

And what we originally found we've seen repeated again and again: Uncontrolled Virtual Distance causes negative impacts on the most important aspects of leadership, financial success, and competitiveness.

As you can see from Figure 1.4, Virtual Distance causes direct and indirect changes to the business goals of financial success and innovation. As you'll see in Chapter 4, when Virtual Distance is reduced, it significantly improves key performance influencers, including trust, organizational citizenship behavior (helping behaviors), employee engagement, satisfaction, learning, role and goal clarity, strategic impact, and leader effectiveness. Virtual Distance has the highest impact on trust and organizational citizenship behavior which leads to many of the other issues.2

FIGURE 1.4 The Virtual Distance Path.

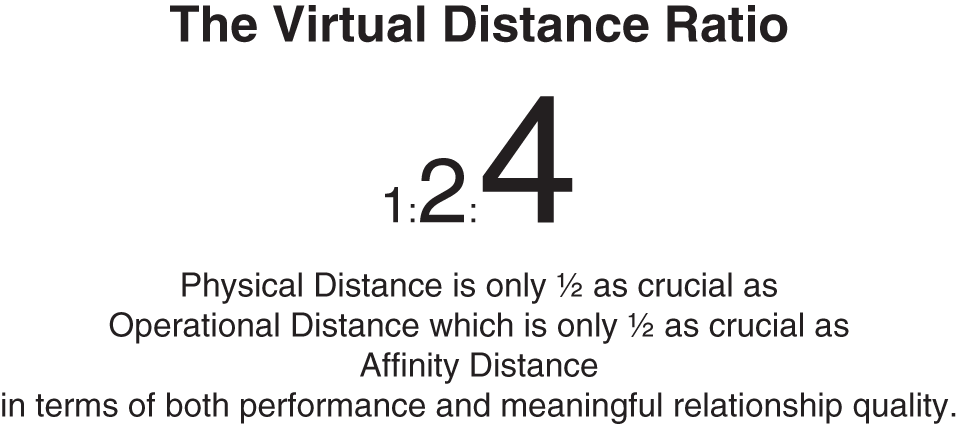

In our first edition we presented the Virtual Distance Formula. However, with the many additional years of data presented in this second edition we can now share what we found as a stable and exponential Virtual Distance Ratio (see Figure 1.5).

As can be seen from Figure 1.5, each of the Virtual Distance factors are related to one another by a mathematical ratio. We can now predict not only Virtual Distance impacts on outcomes, we can also predict each of the individual factors, given any of the other factors.

This mathematical and exponential series gives even stronger quantitative ground to the previously reported power of Virtual Distance.

But it goes beyond that.

Virtual Distance analytics gives way to predictive solutions.

When these solutions are applied in specific sequences and sorted on particular priorities depending on unique Virtual Distance patterns, we've been able to repeatedly demonstrate that our prescriptions yield fast-acting and measurable improvements, including financial boosts to the bottom line, more meaningful relationships among disparate team members, and higher levels of motivation to work together toward shared goals.

FIGURE 1.5 The Virtual Distance Ratio.