The title of this work is marked by the word

Questions, in the plural. It takes the place of the expected singular, along with a definite article, associated with that familiar phrase, “the Homeric Question.” Today there is no agreement about what the Homeric Question might be. Perhaps the most succinct of many possible formulations is this one: “The Homeric Question is primarily concerned with the composition, authorship, and date of the

Iliad and the

Odyssey.”

1 Not that any one way of formulating the question in the past was ever really sufficient. Who was Homer? When and where did Homer live? Was there a Homer? Is there one author of the

Iliad and the

Odyssey, or are there different authors for each? Is there a succession of authors or even of redactors for each? Is there, for that matter, a unitary

Iliad, a unitary

Odyssey?I choose

Homeric Questions as the title of this book both because I am convinced that the reality of the Homeric poems, the

Iliad and the

Odyssey, cannot possibly be comprehended through any one Question, and because a plurality of questions can better recover the spirit of the Greek word

zḗtēma, meaning the kind of intellectual “question” that engages opposing viewpoints. In Plato’s usage,

zḗtēma refers to a question or inquiry of a philosophical nature. This is the word used in the title of Porphyry’s

Homeric Questions, a work that continues in a tradition that can be traced as far back as Aristotle. As Rudolf Pfeiffer writes, “Probably over a long period of time Aristotle had drawn up for his lectures a list of ‘difficulties’ [

aporḗmata or

problḗmata] of interpretation in Homer with their respective ‘solutions’ [

lúseis]; this custom of

zētḗmata probállein may have prospered at the symposia of intellectual circles.”

2A number of quotations from Aristotle’s work are preserved, mostly in Porphyry’s

Homeric Questions.

3 In one of these, Aristotle is disputing the assertion, as found in Plato’s

Republic (319b), that it cannot be true that Achilles dragged the corpse of Hektor around the tomb of Patroklos; Aristotle contradicts this assertion by referring to a Thessalian custom, still prevalent, he says, in his own time, of dragging the corpses of murderers around the tombs of those they had murdered (F 166 Rose).

4 As Pfeiffer goes on to say, “It is an example of the way [Aristotle] used the stupendous treasures of his collections for the correct interpretation of the epic poet against less learned predecessors who had raised subjective moral arguments without being aware of historical facts.”

5 Among the historical facts used by Aristotle is diction,

léxis.

6 For my own approach to Homeric Questions, diction is the primary empirical given.

We will return to the topic of diction presently. For now let us continue with the account by Pfeiffer:

Although certain circles of the Alexandrine Museum seem to have adopted this “method” of

zētḗmata, which amused Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors, as it had amused Athenian symposiasts, the great and serious grammarians disliked it as a more or less frivolous game.… It was mainly continued by the philosophic schools, Peripatetics, Stoics, Neoplatonists, and by amateurs, until Porphyry (who died about 305 [

C.E.]) arranged his final collection of

Homḗrika zētḗmata in the grand style, in which he very probably still used Aristotle’s original work.

7

The title

Homeric Questions reaffirms the original Aristotelian seriousness of

Homḗrika zētḗmata, avoiding the accretive implications of frivolity. To this extent it matches the seriousness of scholarship in the period of the Renaissance and thereafter concerning the Homeric Question. But my title also affirms the need to pose the question in such a way that it will not presuppose the necessity of any single answer or solution,

lúsis. And even if a unified answer were to be achieved in the long run, the result is likely to be a blend achieved from a plurality of different voices, not the singular strain of a monotone edict emanating from the unquestioned authority of accepted scholarship to which some would assign the title of philology.

For purposes of my argument, we need to turn back to earlier understandings of the very idea of

philology. Let us consider, for example, the report of Suetonius that Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who succeeded the scholar-poet Apollonius of Rhodes as head of the Library of Alexandria, was the first scholar to formalize the term

philólogos in referring to his identity as a scholar, and that in so doing he was drawing attention to a

doctrina that is

multiplex variaque, a course of studies that is many-sided and composed of many different elements.

8The era of the great Library of Alexandria reflects a link between our new world of philology and the old world of the actual words that are studied in philology, like the

ipsissima verba credited to Homer. Those who presided over the words, as texts, were the Muses: the very name of the Library of Alexandria was, after all, the Museum, the place of the Muses, and its head was officially a priest of the Muses, nominated by the king himself.

9 These Muses of the text had once been the Muses of performance.

The members of the Museum, which was part of the royal compound, have been described by Pfeiffer: “They had a carefree life: free meals, high salaries, no taxes to pay, very pleasant surroundings, good lodgings and servants. There was plenty of opportunity for quarrelling with each other.”

10 One might say that the Museum itself was a formalization of nostalgia for the glory days when the Muses supposedly inspired the competitive performance of a poet. The importance of

performance as the realization of the poetic art will become clear as the discussion proceeds.

Another head of the Alexandrian Library, Aristarchus of Samothrace, perhaps the most accomplished philologist of the Hellenistic era, was described by Panaetius of Rhodes, a leading figure among the Stoics, as a

mantis ‘seer’ when it came to understanding the words of poetry (Athenaeus 634c).

11 In this concept of the seer, we see again the nostalgia of philology for the Muses of inspired performance.

The beginnings of a split between

philology and

performance—a split that had led to this nostalgia, ongoing into our own time—are evident in an account of Herodotus that I have examined at length elsewhere, concerning two ominous disasters that befell the island of Chios, a reputed birthplace of Homer.

12 In the earliest attested mention of schools in ancient Greece, Herodotus 6.27.2, the spotlight centers on an incident that occurred on the island of Chios around 496

B.C.E., where a roof collapsed on a group of 120 boys as they were being taught

grámmata ‘letters’; only one boy survived. This disaster is explicitly described by Herodotus as an omen presaging the overall political disaster that was about to befall the whole community of Chios in the wake of the Ionian Revolt against the Persians (6.27.1), namely, the attack by Histiaios (6.26.1–2), and then the atrocities resulting from the occupation of the island by the Persians (6.31–32).

The disaster that befell the schoolboys at Chios is directly coupled by the narrative of Herodotus with another disaster, likewise presaging the overall political disaster about to befall all of Chios: at about the same time, a khorós ‘chorus’ of 100 young men from Chios, officially sent to Delphi for a performance at a festival there, fell victim to a plague that killed 98 of them. Only two of the boys returned alive to Chios (6.27.2).

In this account by Herodotus, then, we see two symmetrical disasters befalling the poetic traditions of a community, presaging a general political disaster befalling the community as a whole: first to be mentioned are the old-fashioned and elitist oral traditions of the chorus, to be followed by the newer and even more elitist written traditions of the school. The differentiation between the older and newer traditions, as we see it played out in the narrative of Herodotus, can be viewed as the beginnings of the crisis of philology, ongoing in our own time.

13It is as if the misfortune of the people of Chios had to be presaged separately, in both public and private sectors. The deaths of the chorus-boys affected the public at large, in that choruses were inclusive, to the extent that they represented the community at large. The deaths of the schoolboys, on the other hand, affected primarily the elite, in that schools were more exclusive, restricted to the rich and the powerful.

For our own era, the scene of a disaster where the roof caves in on schoolboys learning their letters becomes all the more disturbing because schools are all we have left from the split between the more inclusive education of the chorus and the more exclusive education of the school. For us it is not just a scene: it is a primal scene. The crisis of philology, signaled initially by the split between chorus and school, deepens with the conceptual narrowing of paideía as education over the course of time.

The narrowing is signaled by exclusion. In the Protagoras of Plato, we are witness to a proposal that girl musicians be excluded from the company of good old boys at the symposium. Even as slave-girls, women lose the chance to contribute to, let alone benefit from, the new paideía. Meanwhile, the traditions of the old paideía, where aristocratic girls had once received their education in the form of choral training, become obsolete. Obsolete too, ironically, is the old paideía of boys, both in the chorus and in the schools. The new schools as ridiculed in the Clouds of Aristophanes seem to have lost the art of performing the “classics,” and the classics have become written texts to be studied and emulated in writing. Gone forever, in the end, are the performances of Sophocles. Gone forever is the possibility of bringing such performances back to life, even if for just one more time, at occasions like the symposium. Gone forever, perhaps, is the art of actually performing a composition for any given occasion.

As I have said, the era of the Museum at Alexandria represents a grand humanistic effort to preserve, even as texts, the

ipsissima verba. To that extent, it also represents an attempt to reverse the narrowing of

paideía. Our own hope lies in the capacity of philology, as also of schools, to continue to reverse such a pattern of narrowing, to recover a more integrated, integral,

paideía. The symptom of a narrowed education can be described as the terminal prestige of arrested development, where schoolboys, instead of getting killed, grow up to be the old boys of an exclusive confraternity that they call philology,

their philology.

14 The humanism of philology, which must surely counter such a narrow modern view, depends on its inclusiveness, its diversity of interests. We come back to the ancient scholarly ideal of a

doctrina that is

multiplex variaque, a course of studies that is many-sided and composed of many different elements. Such a course of studies, I argue, is essential for pursuing Homeric Questions, not to mention other classical questions.

One small but troubling sign of narrowing, of a movement away from a course of studies that is ideally many-sided, is the way in which we contemporary classics scholars—certainly not just Homerists—tend to use the words “right” and “wrong”: this kind of value judgment seems to operate on the assumption that the reader already accepts the argument being offered and rejects all others. The implications are discouraging, because a cumulative plurality of scholars who say “I am right” and “most of you are wrong” suggests that most of those who make this claim are wrong and only some, if any, are right. I propose to write instead, here and elsewhere, that I agree or disagree, without presupposing the ultimate judgment. Or, better, my arguments either converge with or diverge from those of others. I cannot presuppose that I am right, since even a “right” formulation may need to be reformulated in the future, but I, along with all other classicists, need to be wary of a style of criticism that seeks to reformulate our formulations in a style of one-upmanship, where the latest word pretends to be the last word.

15The idea of a

zḗtēma or ‘question’, in the usage of those earliest scholars of Homeric poetry, assumes an ongoing conflict of views in an ongoing debate of scholars. It is in that spirit of open-endedness that I take up my own set of questions, Homeric Questions, making clear my disagreements as well as agreements with other scholars. My goal is to offer a set of answers,

sine ira et studio, that must in the long run be tested by further questions. In my search for answers, I am striving for a definitive formulation of my own thinking on Homeric poetry as it has evolved since my earliest published formulations, which appeared over twenty years ago.

16 Whatever answers I propose, however, leave open-ended the need for further answers—and questions.

The ideal in the academic discourse of my Homeric Questions is

respect for the positive efforts of others. Polemics tend to be reserved for occasions where I countercriticize some criticisms that seem intended to displace or exclude results and views.

17 But I hope in general to transcend the kind of internal battles in classical scholarship where the intensity of contentiousness over the rights and wrongs of interpretation seems at times symptomatic of a specially virulent strain of

odium philologicum, likely to shock even the most cynical specialist in other areas of the humanities. Such marked levels of contentiousness among classicists may be excused as an indirect reflex of the agonistic striving toward the definition of value in ancient Hellenic poetics. Excuses should not distract, however, from a basic shortcoming that seems to result from such strife, namely, an avoidance of new or different methods for fear of being condemned as unorthodox. Such a pattern of avoidance can lead to narrow and consequently oversimplified approaches to complex problems. My goal is to apply a wide enough variety of inductive approaches to do justice to the complexity of the problems addressed.

Failure to apply a broad enough spectrum of empirical methods to a given question is oftentimes not recognized as a failure by the very ones who fail. Ironically, it is sometimes they who will blame newer scholars who may have succeeded in deploying a wider variety of approaches. It is as if the newcomers were rival heirs to a domain called philology. The blame can take the form of accusing newcomers of not having proved what they are seeking to prove. What the blamers may be thereby admitting, however unintentionally, is that they do not know how to use methods that others have found to advance their own arguments. In this connection I am reminded of Terry Eagleton’s formulation, “Hostility to theory usually means an opposition to other people’s theories and an oblivion of one’s own.”

18Yet another problem that can lead to a narrowing of resources in pursuing Homeric Questions has to do with a negative attitude toward the study of earlier stages of Greek literature, deriving from the inference that the further one goes back in time, the less one may really know. This attitude, as I find it articulated by some classicists, comes dangerously close to shunning the study of older evidence on the ground that there is not enough information to prove anything. In resisting such a stance, I take my inspiration from a philologist who studies Greek texts that are even older—as texts—than the Homeric poems. I quote the words of John Chadwick, as he speaks about the Linear B tablets of the second millennium B.C.E.:

Some of my colleagues will doubtless think I have in places gone too far in reconstructing a pattern which will explain the documents. Here I can only say that some pattern must exist, for these are authentic, contemporary sources; and if the pattern I have proposed is the wrong one, I will cheerfully adopt a better one when it is offered. But what I do reject is the defeatist attitude which refuses even to devise a pattern, because all its details cannot be proved. The documents exist; therefore the circumstances existed which caused them to be written, and my experience has shown me that these are not altogether impossible to conjecture.

19

In the case of the Homeric poems, it can be said even more forcefully: not only does the text exist, but even the ultimate reception of the Homeric poems is historically attested, ready to be studied empirically. As I have already indicated, the primary given in my own work is the léxis, or diction, of the Homeric poems. What, then, is the primary question? For me, it is vital that the evidence provided by the words, the ipsissima verba, reflect on the context in which the words were said, the actual performance. The essence of performing song and poetry, an essence permanently lost from the paideía that we have inherited from the ancient Greeks, is for me the primary question.

In choosing language and text as my primary empirical given, I hope to stay within a long preexisting continuum of philologists. In choosing

performance, the occasion of performance, as my primary question, I go beyond this continuum in relying on two other disciplines. These disciplines are linguistics and anthropology.

Let us start with linguistics. Here we can make a distinction between two kinds, descriptive and historical. In the case of descriptive linguistics, the problematic word

structuralism tends to take pride of place in the discourse of classicists, even displacing the very use of the term

linguistics. Too much has been said about structuralism, both for and against, by those who are unfamiliar with the rudiments of descriptive linguistics. For one who was initially trained as a linguist and only later as a classicist, the point is this: the observation that language is a structure is not a matter of theory, not someone’s brilliant insight, but the cumulative result of inductive experience in descriptive linguistics.

20Now we turn to historical linguistics, a method that I have used extensively in my earlier work on Homer.

21 Here, too, we may confront a problematic word: this time, it is

etymology. For example, it has been said about my approach that it “regards alleged etymologies from the distant linguistic past to be some kind of key to Homeric epic.”

22 This is to underrate the value of historical linguistics in the study of tradition: the purpose of connecting the etymology of a Homeric word with its current usage in the Homeric poems is to establish

a continuum of meaning within tradition.

23 An etymology may be a “key” to the diachronic explanation of some reality, as in the case of a cultural continuum, but it cannot be equated with some clever novelty in literary criticism.

24As for the second of the two disciplines that I propose to apply, anthropology, I should note simply that this discipline has as yet exerted so little influence in the field of classics, with a few notable exceptions, that it is seldom mentioned even by those classicists who are given to issuing admonitions against the intrusion of supposedly alien disciplines. Ironically, the field of anthropology has as much to benefit from the currently construed field of classics as the other way around. We find ourselves in an era when the ethnographic evidence of living traditions is rapidly becoming extinct, where many thousands of years of cumulative human experience are becoming obliterated by less than a century or so of modern technological progress, and where the need to reaffirm the humanistic value of tradition in the modern world often cannot be met by the members of endangered traditional societies, who are sometimes in the forefront of embracing the very progress that threatens to obliterate their traditions. The field of classics, which lends itself to the empirical study of tradition, seems ideally suited to articulate the value of tradition in other societies, whether or not these societies are closely comparable to those of ancient Greece and Rome.

The primary Homeric question at hand, that of performance, is not only to be articulated in terms of linguistics and anthropology. It is also to be linked with the past research of two scholars whose training stemmed not directly from these two disciplines but from the classics. It is essential that I invoke these two scholars, both deceased, as we approach the centerpiece of my Homeric Questions. Their names are Milman Parry and Albert Lord. On the occasion of delivering my presidential address at the 1991 convention of the American Philological Association, I stressed what a humbling experience it was for me to be given an honor—and an opportunity—that others before me, who had their own Homeric Questions, would have deserved far more. In particular, I had in mind these two scholars, Milman Parry and Albert Lord, neither of whom was ever awarded such an honor by the American Philological Association. Parry died young, and there was little opportunity for the American Philological Association to recognize the lasting value of his contributions to the study of Homer and to the field of classics in general.

25 In the case of Albert Lord, Life Member of the American Philological Association, whose own important research continued his earlier work with his teacher, Milman Parry, I hope to honor his contributions to classical philology by way of my Homeric Questions, which are meant to serve as extensions of the questions that he had asked in his

Singer of Tales26 and, shortly before his death, in

Epic Singers and Oral Tradition.

273. Hintenlang 1961; Pfeiffer 1968:69.

4. Hintenlang 1961:22–23; Pfeiffer 1968:69.

7. Pfeiffer 1968:70–71, with reference to Lehrs 1882:206.

8. Suetonius

De grammaticis et rhetoribus c. 10 (Pfeiffer 1968:158 n. 8); see the definitive edition of Kaster 1995.

9. Testimonia collected by Pfeiffer 1968:96.

12. N 1990c, restating an earlier discussion in N 1990a:406–413. On Chios as birthplace of Homer, see Acusilaus FGH 2 F 2.

13. N 1990c. See especially p. 40 on Sophocles as composer and performer.

14. N 1990b:47. On the concept of

terminal prestige, see McClary 1989.

15. Phillips (1989:637) makes the following remarks on the “scientific model” of classical scholarship: “The most recent work becomes the most truthful, with the exceptions either of older views which agree with contemporary conceptualizations (hence becoming glimmerings of truth) or which through their apparent ‘error’ provide a point of departure for interpretational polemic or which offer compilations of data as yet not reedited. This ahistorical view of contemporary ‘truth’ makes classical studies akin to the natural sciences.”

16. Householder and Nagy 1972b, esp. pp. 19–26, 35–36, 48–54, 62–70. In my earlier publications, I consistently refer to this work according to the pagination of version 1972a, because of a troublesome typographical error on p. 20 of version 1972b. Still, the latter version is now more easily available and more often cited (e.g., Palmer 1980:72, 74, 105, 316; and Janko 1992:8 n. 2, 11 nn. 10 and 13, 16 n. 27, 17 n. 30, 303); accordingly, I will simply correct the error at p. 20 of version 1972b (

at line 5,

at line 6) and refer to this version hereafter.

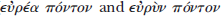

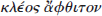

17. An example that comes to mind is this statement by Griffin (1987:103 n. 36: “On the phrase

[

kléos áphthiton ‘imperishable fame’], on which too much has been based, I share the reservations of Finkelberg (1986).” Cf. N 1974, which is indeed based on the Homeric expression

kléos áphthiton (

Iliad 9.413). I offer some counterarguments to Finkelberg 1986 in N 1990a:244–245 n. 126. Cf. Edwards 1985a:75–78 and Martin 1989:182–183.

20. As Meillet (1925:12) points out, each linguistic fact is part of a system (“chaque fait linguistique fait partie d’un ensemble où tout se tient”). We need not expect, however, any such system to be perfect: it is fitting to recall the succinct formula of a noted American linguist and anthropologist: “All grammars leak” (Sapir 1921:38). See discussion of linguistic models in Householder and Nagy 1972b:17; also N 1990a:4–5. Few studies in Homer apply linguistics with the degree of intellectual rigor and flair that this field requires. An exception is Miller 1982a and 1982b: the author reveals a thorough grounding in linguistic theory and praxis. Here I record my own debt to my linguistics teachers, Fred Householder and Calvert Watkins; also to former students, many of whom have published monographs that apply the methods of linguistics (e.g., Bers 1974, Bergren 1975, Shannon 1975, Muellner 1976, Frame 1978, Sinos 1980, Lowenstam 1981, Martin 1983, Sacks 1987, Crane 1988, Caswell 1990, Edmunds 1990, Kelly 1990, Roth 1990, Stoddart 1990, Lowry 1991, Slatkin 1991, Vodoklys 1992, Batchelder 1994, Petropoulos 1994).

21. Especially N 1974, 1979, 1990b.

22. Taplin 1992:116 n. 12, commenting on N 1979.

24. See further debate in N 1994a. More below on the term diachronic. On traditionality as an instrument of meaning, see Slatkin 1991.

25. The collected papers of Milman Parry have been published by his son, Adam: Parry 1971.

27. Lord 1991. I sense that there is a special need to put on record, for the institutional memory of the American Philological Association, the honor that is Lord’s due. This need is prompted not only by the value of his scholarship but also because, as I still remember clearly, one particular APA presidential address, delivered in a previous year on the subject of Homeric composition, seemed to go out of its way to slight Lord’s work.

at line 5,

at line 5,  at line 6) and refer to this version hereafter.

at line 6) and refer to this version hereafter. [kléos áphthiton ‘imperishable fame’], on which too much has been based, I share the reservations of Finkelberg (1986).” Cf. N 1974, which is indeed based on the Homeric expression kléos áphthiton (Iliad 9.413). I offer some counterarguments to Finkelberg 1986 in N 1990a:244–245 n. 126. Cf. Edwards 1985a:75–78 and Martin 1989:182–183.

[kléos áphthiton ‘imperishable fame’], on which too much has been based, I share the reservations of Finkelberg (1986).” Cf. N 1974, which is indeed based on the Homeric expression kléos áphthiton (Iliad 9.413). I offer some counterarguments to Finkelberg 1986 in N 1990a:244–245 n. 126. Cf. Edwards 1985a:75–78 and Martin 1989:182–183.