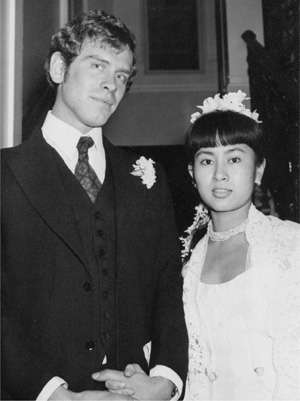

Suu and Michael on their wedding day in London, January 1, 1972.

THEY were married in a Buddhist ceremony in the Gore-Booths’ home in Chelsea, guests wrapping sacred thread around the couple as they sat cross-legged on the floor while a Tibetan lama, Chime Youngdroung Rimpoche, blew on a conch shell. “It was a lovely ceremony,” recalled Sir Robin Christopher, one of Suu’s closest friends from Oxford. “I was one of those who walked around them with the holy thread. What a wonderful bond that was to prove to be!”1 It was charmingly romantic: two anglophone Buddhists, conjoined a few hundred yards from the World’s End and Gandalf’s Garden—before flying off together to make their home in Shangri-La.2

But few romantic stories are quite as enchanted as they appear, and there is none without its shadow. The ceremony was a gracious nod to Suu’s roots and Michael’s fascination with Buddhism, but there were absences that were ominous given Suu’s stature as the Bogyoke’s only daughter. The Burmese ambassador did not show up: The froideur between Suu and the Ne Win regime was now official. More upsettingly, nor did Suu’s brother or mother. Despite the evocative ceremony and the reception at the Hyde Park Hotel afterwards laid on by her generous guardians, it was more like the wedding of an orphan than Burma’s most honored child.

There is no doubting the strength of the love that Suu and Michael Aris felt for each other: There is a gleam in Suu’s eyes in the photographs taken in the early years of their marriage that we have not seen before. Gone is the blank correctness of her expression when she was an Oxford student visiting her mother in Delhi, the air of gloomy abstraction she wore in New York, “serious, sad, uncertain” in the words of Ann Pasternak Slater.3 In a photograph taken in 1973 during their first visit to Burma together, Suu glows in a way that is quite new. She and Michael are pressed together on the floor in a room washed with sunshine, both dressed in white, gazing at the camera. Michael appears dazed with happiness, Suu looks practically beatific. In a photograph taken the same year in Nepal, she cradles her baby boy Alexander and beams open-mouthed at the camera from under her fringe, showing her sparkling teeth, and looking more like a Burmese Audrey Hepburn than one would think possible.

Suu and baby Alexander.

They look like the perfect modern couple: Buddhist to a degree—both steeped in its ideas and ceremonies and art works—but never in thrall to superstition, unmistakably secular, late-twentieth century young people, their differences of race and upbringing dissolved in the hot sun of their love for one another; the conventional expectations of an older generation—settling down, finding a career—rendered irrelevant by the wonderful prospect of setting off together on a great adventure. And the adventures really happened: A year in Thimphu, where hardly any foreigners had spent even a fortnight; the best part of another year in Nepal, tiny baby in tow, with side-trips to Burma; later long trips to Japan, to the Indian Himalayas.

That’s the bright side of the picture. What of the shady side?

It is the story of many a modern woman who finds herself in what turns out to be, almost by default, a rather traditional marriage—often despite the best and most enlightened intentions of both partners.

Since they had first met in Chelsea, Michael had got his lucky break and run with it: He had spent nearly five years immersed in the language, culture and history of Bhutan and Tibet. Those years were to be as fundamental to his future career as the voyage on the Beagle was for Charles Darwin. From now on, no one in Tibet studies would get away with calling him a dabbler.

And Suu? She had taken a mediocre degree, done a little part-time tutoring and a little temporary research work, obtained a postgraduate position in New York which she abandoned weeks later; and then had used her name and connections to get a semi-menial job in the United Nations, from which she resigned after three years to get married. She was the proud daughter of a great man but had achieved next to nothing on her own account—and, more disturbingly, did not seem to have a compass of her own. Unable to forget who she was, she had attached ferocious conditions to her marriage “. . . should my people need me . . .”—but in the meantime she was that unfortunate creature: a trailing spouse.

*

They flew off to Bhutan, where Michael, now thoroughly at home, continued as tutor to the royal family while deepening his knowledge of all things Bhutanese. During his free time they trekked through the kingdom’s vertiginous valleys, sometimes on foot, sometimes on ponyback; at least once they were obliged to ride on the roof of a lorry, and snacked on the fruit of the Asian gooseberry trees they passed under.

For Michael it was the coda to his years of primary research: By the end of it he had enough material, he believed, to write the doctoral thesis that would be the next vital step in his career. For Suu, by contrast, it was an exotic interlude but not much more. The scenery was magnificent, though repetitive; the local cuisine, in which pork fat and chilies played a dominant role, was largely inedible, she confided to a friend in Rangoon—“we were hungry all the time,” she said.4 In response to her appeals, her mother sent that eye-watering staple of Burmese cuisine, fried balachaung—pounded dried shrimp and fish paste deep-fried with sugar, chili and tamarind paste—packed in empty Horlicks bottles. On one occasion the package arrived but the bottle was cracked at the bottom; they debated whether they should throw it out because of glass shards but ended up eating it at a single sitting.

Keeping Suu company during Michael’s frequent absences was a Himalayan terrier puppy called Puppy, a gift of the king’s chief minister. Suu became extremely attached to her new pet. It accompanied them back to England, and was with them throughout the family’s years together—a talisman of their togetherness, as cherished pets often are. When she learned that Puppy had finally died at an advanced age in her absence—word arrived while she was traveling around Burma in 1989, campaigning for her party—the news broke her heart.

Suu with Michael’s siblings and brother-in-law, plus dog. They all struck up a warm relationship with the family’s new member.

Suu and Michael in Bhutan with their new puppy, forever to be known as Puppy, to which Suu became very attached.

Bhutan joined the United Nations while Suu and Michael were in residence, and Suu advised the kingdom’s minuscule Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the mysterious ways of that body. She also taught English to a class of royal bodyguards, but her fierce efforts to keep order reduced them, by her own admission, to cowering shadows of their normal hulking selves. Michael learned to drive on Thimphu’s almost empty roads, but his attempts to pass on his new skills to Suu were not a success. Then in August, eight months after their arrival, Suu discovered she was pregnant, and they decided to go home.

By Christmas they were back in London. Michael wanted to write a doctoral thesis at SOAS on the early history of Bhutan, based on what he had learned during his years of residence there; his supervisor was to be the man who was already his mentor in Tibetan studies, Hugh Richardson. With Michael’s family’s help they bought a tiny flat in Brompton, not far from the Gore-Booths, and on April 12, 1973, Suu’s first son Alexander was born.

Suu with Hugh Richardson, Michael Aris’s mentor in Tibetan studies and the last British resident in Lhasa before the Chinese invasion. In 1981, after his death, Suu and Michael co-edited a volume of essays in his memory.

As any parent knows, the first year of a child’s life is a unique time when many things are possible that become unthinkable afterwards, and within a few weeks of Alexander’s birth Michael and Suu were heading back to Asia with their baby. Word of Michael’s special expertise was getting around the world of Tibetologists, and he had been asked to lead an expedition to Kutang and Nubri, two remote areas in northern Nepal having much in common culturally with Bhutan. They were away from Europe for nearly a year.

Probably more significant for Suu were the two visits they paid to Rangoon during that period, the first one to introduce Alexander to his grandmother. If the couple were anxious about what sort of reception to expect from Daw Khin Kyi, they were to be relieved: Despite her earlier misgivings, she decided that she was well satisfied with this genial and learned young man. “She was very pleased with him,” wrote Suu’s former personal assistant Ma Thanegi in her diary. One thing she appreciated were his old-fashioned English manners. “When Suu was out somewhere, Michael would not touch his food until she returned,” she went on. “Once when Michael was out, Suu was so hungry she wanted to sit down to eat right away. Her mother reminded her gently that he always waited for her. So she felt she had to wait, too.”

Suu, Michael and Alexander with Daw Khin Kyi, during their first visit to Burma after the wedding. Despite her initial doubts about Suu marrying an Englishman, Daw Khin Kyi got on well with Michael.

*

Daw Khin Kyi must have been glad of their company, because her life since her retirement from Delhi in 1967 had become one of almost total seclusion: She left 54 University Avenue once a year, for an annual medical check-up, but otherwise remained there all the time.5

She did not live like a hermit: She had always been a generous and amusing host, and intellectuals, former politicians, disgraced army officers and foreign diplomats streamed through her living room, avid for the latest gossip about who was in and who was out, who up and who down. But she gave no ground in the silent war she waged with the tyrant across the lake.

Both Daw Khin Kyi’s resistance and her reticence—her refusal to give an inch to the regime, while at the same time declining, hedgehog-like, to expose herself to any sort of attack—indicate a deep understanding of the pitiless nature of the political game as played in her country, and as mastered by Ne Win. In this game, the illustriousness of an opponent was not a reason for holding back, but on the contrary a reason to attack with every weapon that came to hand until victory was total. The most flagrant example of this was the way Ne Win humiliated the corpse of U Thant, a few months after Michael and Suu’s second visit.

*

Suu’s old boss at the UN had retired as Secretary General in 1971, not long before she herself left the organization. Already unwell, he told the General Assembly that he felt “a great sense of relief, bordering on liberation” at relinquishing “the burdens of office”: His last years in the job had been particularly testing. He died of lung cancer less than three years later, in November 1974. His daughter and son-in-law and their young son accompanied his coffin on the then long and tedious air journey back to Rangoon for burial.

It is not clear what sort of reception the family expected to receive in Burma, or if they were fully aware of the depth of the rift that had opened up between U Thant and Ne Win. But when their charter plane taxied to a halt at Mingaladon Airport, no government officials were on hand to welcome them, nor was there a government hearse or limousine to collect the coffin and the mourners.

The deputy education secretary, U Aung Tin, turned up—but only because he had been a pupil of U Thant’s when the great man was a provincial headmaster and he could not bear to be part of the systematic snubbing that was under way. When, at a cabinet meeting, he proposed that the day of the funeral be declared a national holiday in the dead man’s honor, he was sacked on the spot.

The coffin was eventually collected from the airport by a beaten-up Red Cross ambulance and taken to an ad hoc wake to the former racetrack, so the ordinary people of the city could pay their respects. A floral wreath placed nearby was signed, eloquently enough, “seventeen necessarily anonymous public servants.”

Enmity between the two most powerful Burmese of their generation had been festering for years, but according to U Thant’s grandson Thant Myint-U, who as an eight-year-old boy accompanied U Thant on his last journey home together with his parents, what had tipped Ne Win over the edge was the behavior not of U Thant himself but of the man to whom he had for years been secretary and close adviser, U Nu.

U Thant was exquisitely diplomatic, long before becoming the highest-ranking diplomat in the world; back in the 1950s he had single-handedly rescued a prime ministerial visit by U Nu to Russia from disaster after the Burmese prime minister had unilaterally, and for no reason that had anything to do with Soviet–Burmese relations, taken it into his head to attack Khrushchev for his government’s repressive policies towards Soviet Jews. After several outbursts on this theme by U Nu, followed by private Soviet complaints, U Thant had managed to make his boss see sense, rewriting all his pending speeches to save Burma’s relations with the second superpower from hitting the rocks.

Given the loose-cannon propensities of the former Burmese prime minister, it was unfortunate that U Thant should have been away in Africa in early 1969 when both U Nu and Ne Win, already settled enemies, visited New York at the same time. U Nu was in the early stages of trying to rebuild his political career, and he took advantage of his old friend’s absence from town to call a press conference inside UN headquarters at which he fiercely denounced the Ne Win regime and all its works, and called for a revolution.

“Never before,” wrote Thant Myint-U, “had a call for the overthrow of a UN member state government been made from inside the UN.”6 U Thant called U Nu, rebuked him, and extracted an apology, but it was too late to salvage the amour propre of the paranoid and irascible dictator. “General Ne Win was upset,” Thant Myint-U wrote, “and became sure that U Thant was now conniving with U Nu. He told his men to consider Thant an enemy of the state.” When the Secretary General went home on a private visit the following year, Ne Win refused to see him; when he needed to renew his passport, the regime made it insultingly difficult. But Ne Win’s best opportunity for revenge came when U Thant was dead.

The coffin lay where it had been placed on the uncut grass in the middle of the disused racetrack. More and more people thronged to the site to say goodbye to the dead man, but the next day the state media claimed that the family had broken Burmese law by bringing the body home without permission and could face legal action. Eventually—U Thant had been dead a full week by now—permission came for a funeral, but the burial ground for Burma’s greatest statesman was to be a small private cemetery.

The family, their grief now exacerbated by fear, anger and stress, would have swallowed this final humiliation for the sake of getting the great man into the ground and the whole miserable business concluded. But it was not to be.

It so happened that 1974 was a watershed year for the Ne Win regime. Tin Pe, the so-called “Red Brigadier,” had for years been the most powerful figure in the Revolutionary Council (which was replaced in 1972 by a pseudo-civilian government with the same cast of characters). Advocating a rapid conversion of the economy to Marxist orthodoxy, he oversaw the nationalization of practically everything, including, crucially, the purchase and distribution of rice. The destruction of the market and its replacement by a command system had the same effect in Burma as everywhere else: Productivity plummeted, and the black market boomed. In British days Burma had been known as Asia’s rice basket, but now productivity was falling year by year. As early as 1965 Ne Win, in one of his moments of startling frankness, admitted that Burma’s economy was “a mess” and that everyone would be starving if the country were not so naturally fertile.

By 1970 the Red Brigadier’s luck had run out and he was forced to retire, but the evil effects of his reforms continued to be felt. The price the state paid for rice was so low that farmers either hoarded it or sold it on the flourishing black market. This forced the government to reduce the ration of low-priced rice, forcing consumers to supplement it by buying more on the black market—for twice the price. It was a vicious circle.

The result was unprecedented social unrest, which began with strikes in the state railway corporation in May and spread rapidly to other industries. Massive demonstrations were brutally suppressed by the army. In August the whole situation became very much worse when widespread monsoon flooding led to an outbreak of cholera.

And then the corpse of U Thant came home—and its treatment by Ne Win gave the students, who were as usual at the sharp end of the protests, the symbol they sought. Here was a man regarded by millions of Burmese as a national hero being dealt with like a pariah by the man who was dragging the whole nation into poverty and enslavement. It was intolerable.

On the day of the funeral, Thant Myint-U was left behind at the home of his great uncle: His parents feared that the funeral procession might encounter trouble, and they did not want their son to be exposed to it. So Thant Myint-U was not on hand to witness the extraordinary—and, for the family, deeply upsetting and traumatic—events of that day. He wrote:

The Buddhist funeral service went as planned, but then, as the motorcade began driving towards the cemetery, a big throng of students stopped the hearse carrying the coffin. They had been arriving all day long in the thousands, with thousands more onlookers cheering them on. Through loudspeakers mounted on jeeps they declared, “We are on our way to pay our tribute and accompany our beloved U Thant, architect of peace, on his last journey.” One of my grandfather’s younger brothers pleaded with them to let the family bury him quietly and to take up other issues later, but to no avail. The coffin was seized and sped away on a truck to Rangoon University.7

One of the students involved, now a senior editor in Rangoon, said, “We put the coffin on a truck and thousands and thousands of us marched towards Rangoon University campus. First we put it in the Convention Hall—we had no plan—and then we started asking for a burial ground in an honorable place and we said we will bury him, and people started giving us money to make a huge tomb for him . . .”8

So began a stand-off that lasted for days. The coffin was “placed on a dais in the middle of the dilapidated Convention Hall, ceiling fans whirring overhead in the stifling heat,” Thant Myint-U wrote.9 Tens of thousands of people poured into the campus, and the mood of hostility took on a political complexion as students stood up to condemn not merely the regime’s treatment of U Thant but their repression of dissent and their disastrous economic policies as well.

Eventually the regime offered a compromise: There would be a public but not a state funeral, and U Thant would be buried at the foot of the Shwedagon pagoda. But as the coffin was about to be transported for the second attempt at burial, the students hijacked it again. The former activist recalled:

We took it to the site of the Students’ Union building, near the gate of the campus, which Ne Win had blown up in 1962 with students inside, a few months after his coup d’état, and we buried it there. We called it the Peace Mausoleum. That infuriated Ne Win, and the thing escalated.

Finally after five days the troops stormed onto the campus in the middle of the night and started shelling us with tear gas. We picked up the shells and threw them back but we were outnumbered, and then they started using guns, shooting live ammunition. So we went deeper into the campus where there were some hostels for students, and we tried to defend ourselves with Molotov cocktails, but they were much cleverer than us. They surrounded the buildings, and when we started throwing stones and Molotov cocktails at them they took the students who had already been arrested and used them as human shields, so we couldn’t attack. And then they started shooting at us with real bullets and everything so we surrendered and got arrested.10

At least nine students were killed that night, and the true figure may be much higher; hundreds more were arrested, and many ended up serving long terms in jail. As the coffin was taken under an escort of troops and armored personnel vehicles for its second interment, more riots broke out in various parts of the city, destroying a police station and wrecking a government ministry and several cinemas. Troops again opened fire to quell the protests, and the city’s hospitals were inundated with the wounded.

U Thant was finally laid to rest at the Cantonment Garden near the Shwedagon pagoda as the riots and the fiery military backlash continued. “At about six that morning we were woken up at our hotel by a phone call,” Thant Myint-U wrote. “The caller, who identified himself as a government agent, said that U Thant’s body had been retrieved from the university . . . They said there had been no violence and only tear gas had been used. My family was allowed to pay their last respects. We were asked to leave the country and about a week later headed back to New York. Only much later did we realize the full magnitude of what had happened that day.”11

The aftermath of this explosion of student fury was a crackdown by the regime on the entire student and youth population, militant and otherwise. Martial law was declared and Mandalay and Rangoon Universities were shut down and did not reopen for five months. And there was cultural repression, too—Ne Win’s Taliban streak coming out again. Trousers of all sorts but particularly jeans were outlawed, along with all other imported western fashions, and all male students with long hair were forced to have it cut short. And this did not mean a trip to the beauty salon. “The abiding image I have of the U Thant riots,” wrote Harriet O’Brien, who was then living in Rangoon with her diplomat parents, “[is] of a student friend with his hair cut off in tufts . . . He had been dragged from the street by soldiers who had forcibly hacked off his hair with their bayonets.”12

*

Suu and Michael learned to their horror how the last rites for Suu’s old boss had given rise to the bloodiest political confrontation since independence. But there was never any question that this scholar’s wife with her new baby would make some kind of public declaration about the affair. Indeed she had explicitly promised that she would do nothing of the sort. A few months earlier—after the rice protests but before the floods and U Thant’s death—Suu and Michael were visiting Daw Khin Kyi for the second time together, Alexander being at the time a little over one, when officials of the government called Suu in and asked her whether she planned to get involved in “anti-government activities.”13 She told them that she would never get involved in Burmese affairs as long as she continued to live outside the country. She was as good as her word.

But already it seems she was brooding on her duty. On a visit to Rangoon the following year she met retired Brigadier Kyaw Zaw, one of Aung San’s Thirty Comrades. “Uncle, I’ve heard that these days you are mostly looking after your grandchildren,” she told him chidingly. “Do you think you have completed your responsibilities to your country?” Kyaw Zaw, who recorded the exchange in his memoirs, replied, “Rest assured I will continue to meet my obligations to the nation—but you also need to do your part.”14

*

As Rangoon was getting its first taste of People Power, Suu, Michael and Alexander were back in England, and in some uncertainty about what to do next. The Brompton flat that had been just adequate for two was impossible when there was a third who was already toddling. Michael was in discussions with the staff at SOAS about his PhD but so far they were inconclusive. So to find the peace and quiet he needed to organize the results of his six-year stay in Bhutan, the family moved in with Michael’s father and stepmother, John and Evelyn Aris, in the large home in Grantown-on-Spey, in the Highlands of Scotland, where they had retired. They remained there for several months, and when they went south again it was to settle not in London but Oxford. SOAS had accepted Michael’s proposal for a PhD on the historical foundations of Bhutan, and St. John’s College Oxford had awarded him a Junior Research Fellowship which would give him a modicum of financial backing.

The family moved first to a cottage in the village of Sunninghall outside Oxford—“a pretty but impractical house” Ann Pasternak Slater called it—but then in 1977 St. John’s gave them a college flat around the corner from Suu’s old college.15 That same year their second son was born and named Kim, in honor of Suu’s favorite Kipling character. Ten years after graduating, she was back in her old neighborhood, with a husband and a family. And because many people who study at Oxford contrive to stay on indefinitely afterwards, there were friendships to be dusted off.

“Memories of that time are still sunlit but with a sense of strain,” wrote Ann Pasternak Slater, whose home in Park Town was less than half a mile from the Arises’ flat in Crick Road. “The flat was on the ground floor of a pleasant North Oxford house. But its apparent spaciousness was deceptive. Apart from the large, south-facing living room, where all the family life took place, on the gloomier northern side was a tiny kitchen, one bedroom and a box-room doubling as a nursery and frequently occupied spare room.”16

Suu believed in the open-armed tradition of Burmese hospitality that she had grown up with: Visitors to the flat included Ma Than É from New York, who spent long periods with them every year, and numerous visitors from Burma and Bhutan. But Suu was welcoming them all—without the help of the servants who had been a fixture of her childhood homes—in the harsher climate of England, with two small children to look after and a husband who was otherwise engaged. She became fantastically busy.

“On my way to the library I often saw Suu laboriously pedaling back from town, laden with sagging plastic bags and panniers heavy with cheap fruit and vegetables,” Pasternak Slater wrote.

When I called in the afternoons with my own baby daughter, I would find her busy in the kitchen preparing economical Japanese fish dishes, or at her sewing machine, in an undulating savanna of yellow cotton, making curtains for the big bay windows, or quickly running up elegant, cut-price clothes for herself. Michael was working hard at his doctorate. Alexander had to be cared for without disturbing him. There were endless guests to be housed and fed. Still Suu maintained a house that was elegant and calm, the living room warm with sunny hangings of rich, dark Bhutanese rugs and Tibetan scroll paintings. But battened down at the back, hidden away among the kitchen’s stacked pots and pans, was anxiety, cramp and strain.17

“Michael and Suu complemented each other, it was a marriage made in heaven,” said Peter Carey, an Oxford don and a close friend. “Not because it was all roses, because it wasn’t, it was a very rocky road.”18 Robin Christopher has a memory of Suu ironing everything in sight, including Michael’s socks: “It was a role she performed with pride,” he said, “and with a certain defiance of her more feminist friends.”

Suu became close friends with another academic wife, a Japanese woman called Noriko Ohtsu whose husband was also on a research fellowship at the university.

“It was actually her husband Michael who I got to know first,” Noriko said. “I met him in 1974 when we were both students of Tibetan at the School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS] in London. I liked him from the word go: No one could call him exactly handsome but there was a big-hearted gentleness about him that made people feel comfortable.”19 He told her about his years in Bhutan, and she found something comically appropriate about it: He reminded her of the Abominable Snowman. “With his unkempt hair and his great height he looked like a giant who had just emerged from the Himalayas. The first thing he said to me, with evident pride, was ‘My wife is Burmese.’”

As chance would have it, we all moved from London to Oxford in 1975: I and my Japanese husband Sadayoshi, an expert on the economy of the Soviet Union, and Suu and Michael and their toddler Alexander. As a result we all got to know each other much better. It helped that both Suu and I were from Asia, in a city where people from our part of the world were few and far between. There was an intimacy to our friendship that I found with none of my other Oxford friends.

My first sight of Suu when I met her in London was of this beautiful young girl pushing a pram, wearing Burmese dress, her hair in a pony tail with a fringe hanging down over her forehead. She looked like a teenager: I couldn’t believe she was twenty-nine, one year older than Michael, who looked old enough to be her father.

Suu was already interested in Japan because of her father’s deep involvement with the country before and during the war. And despite the many differences between their two nations, there was also much in common: instinctive courtesy and self-effacement, for example, and a habit of diligence and graceful attention to everyday tasks.

“We exchanged recipes and went shopping together in Oxford’s covered market,” Noriko remembered.

We went window-shopping for Liberty prints then snapped them up when the price came down in the sales and Suu would run the fabric up into longyi.

Michael was trying to make ends meet with his research about Tibet but their income was very small, and Suu would say to me, “Noriko, we’re down to our last £10! What on earth can I do?” But she was brilliant at making delicious meals out of cheap ingredients, and I helped out whenever I could by inviting the family round for a Japanese dinner.

The multiple challenges of running the family single-handedly—“Michael couldn’t cook properly,” Noriko recalled, “it was always Suu that cooked”—brought out a trait of puritanical perfectionism in Suu, Pasternak Slater recalled. “She could be very critical and very disapproving—to me and certainly to Michael,” she said.

I remember me driving her down to some rather tatty budget furniture shop and me saying, “Why on earth do you want to buy this sort of crap? Why don’t you buy an antique?” And she would say, “This is perfectly good, there’s no need to be spending money on antiques.” I was spending money on pine blanket boxes and the like while she was getting stuff from this cheap place and she probably thought I was a kind of cultural snob, I suppose. It was part of her practicality: There was no need to have something grandiose, it’s just children’s furniture, what the hell.20

On cut-price food, by contrast, she was unbending. “Her pride did not permit any compromise with fish and chips, burgers or other such fast-food solutions,” said Noriko. “She always tried to feed her family with freshly cooked home-made food.”

She was also becoming a stickler for traditions, including those not her own. She didn’t like Christmas pudding, and never ate it, but nonetheless she ritually made one six months in advance. When she visited Noriko in Japan, years later, she even took one with her as a present—even though neither of them liked the stuff. She showed no signs of converting to Christianity, but she is remembered by another Oxford friend as the first person to get her Christmas cards out every year. And she visited the Victorian severity of her mother on her own children and their friends. As her babies grew, Ann Pasternak Slater, who now had four children of her own, remembered, “It was Suu who gave the copy-book parties with all the traditional party games—except that the rules were enforced with unyielding exactitude, and my astonished children, bending them ever so slightly, once found themselves forbidden the prize. To them Suu was kindly but grave, an uncomfortably absolute figure of justice in their malleable world.”21

She was equally unbending about telling the truth, even at the risk of offending people, and was appalled and uncomprehending when Michael did otherwise. Noriko remembered one conversation in which the subject of British social hypocrisy came up.

She and Suu were in agreement about the abysmal quality of much British food. Suu said to her in Michael’s presence,

Noriko, as you well know, some British food is really awful. When we get invited out to eat and the food is bad, I don’t say it’s delicious: I’m a person who does not tell lies. But if they ask Michael, he always says, “Thanks for the delicious meal!” Staring at Michael she added, “Why does he always do that?”

Michael replied, “It’s a matter of courtesy, it’s a way of expressing my gratitude.” “There’s no need for it,” Suu retorted, “I wouldn’t do it.” She turned to me. “Michael was brought up eating bad British food in boarding school,” she said, “so he’s become insensitive to it.” Michael just rounded his eyes, looked up at the ceiling and shrugged.

That was Suu and Michael’s life encapsulated in one scene. Whatever you said to Michael he would just smile. Because he knew that as long as he and Suu were together he would get home-cooked food to eat.

He was a lucky man and he knew it. “For the first fifteen years of the marriage it was all Michael,” said Peter Carey, “the fellow of St. Antony’s, the fellow of St. John’s, the great scholar of Bhutan and Himalayan Buddhism. He was the breadwinner, the core of the marriage, and she was the helpmate, the north Oxford housewife. She was her father’s daughter, but she had transmogrified into this north Oxford inheritance.”22

With her closest friends, Suu expressed some of her frustration. In 1978 Michael completed his dissertation and obtained his doctorate, but Suu felt that subsequently he did not try hard enough to capitalize on that hard-won achievement.

“I think Suu thought that he could actually have pushed his way a bit more,” said Ann Pasternak Slater. “She felt that he was not proactive enough. She said I was very lucky to have a husband who was a bit more of a wheeler-dealer. It was partly him not being as go-getting and achieving as my husband was—I didn’t need to tell Craig what to do but she felt she had to be pushing Michael and she said she envied me a husband who didn’t need that.”23

Suu’s was the common lot of the modern mother who, despite her qualifications and professional experience, finds herself laboring away at menial tasks while her husband is absorbed in the—painfully slow—construction of his glorious career. But in Suu’s case there was an extra twist: With both her sons she was unable to be as complete a mother as she felt was both her duty and her right. As Michael struggled with his Tibetan texts in their cramped flat, Suu struggled and failed to breastfeed her second child.

Pasternak Slater recalled:

She had been unable to breastfeed Alexander, too, and Kim was very, very difficult. Michael was understandably desperate to finish his thesis and this created a lot of friction because there was this baby who wouldn’t sleep and Suu trying to feed him and so it was very hard. She wasn’t able to in the end, she had to give up. I doubt whether the anguish she felt can be understood by anyone who has not had the same experience. Especially because at that time everyone was saying breast is best, it was very much the thing. So in the end Kim had to be taken into a pediatric unit to try and spend nights away from Suu so he didn’t scream all night long.

Both boys ended up being bottle-fed. It was a telling demonstration of how Suu’s indomitable willpower could sometimes backfire on the whole family. Her pain, said Pasternak Slater, was “the inevitable result of her rooted reluctance to accept defeat, or to allow herself the indulgence of a second-best way.”

*

By 1980, the family’s situation was beginning to improve. Michael’s doctorate had been rewarded with a full research fellowship provided by Wolfson College, which also came with a bit more money. They had moved from the tightness of the college flat to their first—and, as it turned out, only—proper family home, across the gated gardens from Ann Pasternak Slater and her family in Park Town. Alexander had started going to the Dragon School, a posh preparatory school in north Oxford; Kim would follow him there soon. And Suu was at last able to raise her eyes from the sink and the sewing machine and consider her options.

“She was very much casting around for a role for herself,” remembered Carey. “She said, is this my destiny to be a housewife, the partner of an Oxford don?”24 Ann Pasternak Slater said, “She was becoming more serious, more focused, more determined, more ambitious.”25

She started helping Michael in his work, and in a volume of essays dedicated to Hugh Richardson, who had died in 1979, she was named as co-editor.26 She found a part-time job in the Bodleian, Oxford’s famous library, working on its Burmese collection. She made another effort to go back to college, applying to take a BA in English, but her third-class first degree was held against her and she was turned down. “All those years spent as a full-time mother were most enjoyable,” Suu said in an interview many years later, “but the gap in professional and academic activity—although I did manage to study Tibetan and Japanese during that time—made me feel somewhat at a disadvantage compared to those who were never out of the field.”27

So instead she set about realizing one of her earliest childhood ambitions and turned herself, in a modest way, into a writer.

She wrote three short books for schoolchildren about the countries she knew best, Burma, Bhutan and Nepal, books she rightly dismissed later as potboilers. More significantly, she also wrote a slim biography of her father, Aung San of Burma, published by Australia’s University of Queensland Press in 1984. In his biography of Suu, Justin Wintle described it as “idealized.” It is certainly not iconoclastic, and it is too brief to stand as a major work of scholarship, but it is written in a clear, limpid style and is shot through with insight and affection.

Aung San, she wrote, “has left an unflattering description of himself as a sickly, unwashed, gluttonous, thoroughly unprepossessing child who was so late beginning to speak that his family feared he might be dumb . . . While his three brothers started their education early, he refused to go to school ‘unless mother went too’ . . .”28

In the last paragraph of the book’s concluding chapter, she described what it was about Aung San that had made him such a popular and successful leader. The words were an implicit denunciation of what, under Ne Win, leadership in Burma had come to mean; they would also become a sort of manifesto for herself. She wrote:

Aung San’s appeal was not so much to extremists as to the great majority of ordinary citizens who wished to pursue their own lives in peace and prosperity under a leader they could trust and respect. In him they saw that leader, a man who put the interests of the country before his own needs, who remained poor and unassuming at the height of his power, who accepted the responsibilities of leadership without hankering after the privileges, and who, for all his political acumen and powers of statecraft, retained at the core of his being a deep simplicity. For the people of Burma, Aung San was the man who had come in their hour of need to restore their national pride and honor. As his life is a source of inspiration for them, his memory remains the guardian of their political conscience.29

As her children grew, her thoughts were turning again restlessly to Burma. She had been going back most summers, alone or with the family, to keep her mother company and pay homage to her father on Martyrs’ Day. Later—one year before her mother’s devastating stroke—she took the boys back for shinbyu, the ceremony all Burmese Buddhist boys undergo between the ages of five and about twelve, when they re-enact the Buddha’s renunciation of his royal heritage and his decision to embrace the life of the spirit. Suu had not taught Alexander and Kim to speak Burmese but they both had Burmese as well as English names and passports. And now they also had the most important Burmese rite of passage behind them.

It was on one of these visits that she struck up a friendship that was to prove important to her later on. She visited Rangoon University to seek out copies of Burmese classics on behalf of the Bodleian and got talking to one of the senior librarians, whose name was Ko Myint Swe, a friend of her mother’s. “You must help our country,” he told her. “But how, uncle?” she replied.30 Myint Swe was not sure: But he was one of several voices in Rangoon reminding her who she was, and that she might yet have a role. When she took the plunge and entered politics in 1988, Myint Swe became one of her closest aides.

Both her boys were now at school, and Suu decided that the best way to re-engage with her country was as a scholar. Following in Michael’s footsteps, she applied to SOAS in London to do a PhD on Burmese political history, which would give her the opportunity to expand the slim biography of her father into a full-blown scholarly work. But again her cursed third in PPE came back to haunt her and she was rejected: Her assessors felt that her grasp of political theory would be insufficient to see her through.

Suu was livid at this new rejection, but then it was suggested that she might write a thesis on modern Burmese literature instead. She took a one-year course at SOAS in preparation, reading numerous works in Burmese, working one-on-one with her tutor Anna Allott, and finally sitting an exam.

“We read several novels together,” said Allott, “and I asked her to write essays about them and what she wrote was very illuminating because she wrote from a Burmese point of view.”31 The exam tested her command of the language and her knowledge of modern Burmese literature and she passed easily.

At SOAS she also learned about a research fellowship offered by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University in Japan. Suu applied and was awarded a research scholarship for the academic year 1985–86, to study Burma’s independence movement. This would be her opportunity to delve into the Japanese archives and learn firsthand what experiences her father had undergone in Japan. Her plan to write the big biography of her father may have been shunted aside but it had not been derailed. With her customary determination she plastered the bathroom at Park Town with blown-up kanji, Japanese characters, and set about learning to read Japanese in world-record time.

The family was on the go again: Suu was to move temporarily to Japan, taking eight-year-old Kim with her—he would undergo a very challenging year in a Japanese primary school—and at the same time Michael went with Alexander to Shimla, high in the Indian Himalayas, where he had won a two-year fellowship at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies. The four of them would get together for the holidays.

*

She was back in Asia: She had not spent so long in an Asian country since leaving Delhi for Oxford eighteen years before. Japan was in the middle of the biggest economic boom in its history—a phenomenon that interested her as little as the hippies of London or the Velvet Underground in New York. But to be in the country which had offered so much to Burma, and delivered so little, and so ambiguously—that was interesting, and difficult. It was a brother nation to Burma, it had offered liberation from the white man and fellowship in the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, but on closer acquaintance that had proved to be an even more onerous form of colonialism under a fancy name.

Suu loved Japanese food and appreciated Japanese diligence and culture, but she was critical, too. She found the people arrogant and obsessed with making money, and she couldn’t understand why, despite their great aesthetic sense, they built such hideous modern cities. Her father had been shocked to be offered a prostitute during his stay in Tokyo—and she was appalled at the way Japanese men bossed and bullied women, in a way that would not be tolerated in Burma.

She shuttled between Kyoto and Tokyo to interview war veterans who had known her father, and dug for raw material on Aung San in the libraries of the Self-Defense Forces, the National Library and elsewhere, plundering them for anything she could find on him.

Yet in the opinion of Noriko Ohtsu, her Japanese friend from Oxford who had returned to live in Kyoto, her hometown, the academic slog was in the long run less important than her own transformation. In an interview years later, Suu said, “When I was young I could never separate my country from my father, because I was very small when he died and I’d always thought of him in connection with the country. So even now it is difficult for me to separate the idea of my father from the concept of my country.”32 And those months of immersion in her father’s life and work were, in her friend’s opinion, crucial for Suu: a first kikkake, as she puts it, a turning-point, in the fitful, unplanned process of realigning her destiny with Burma’s.33

At the weekends, Suu and Kim sometimes visited Noriko and Sadayoshi at their place in the countryside overlooking Lake Biwa, and during the months in Japan Noriko witnessed a transformation come over her friend. At the university she encountered Burmese exchange students who treated her with a mixture of deference and vague yet intense expectation that was quite novel to her.

“She and Kim were staying in International House, Kyoto University’s residence for scholars,” Noriko said, “and there were young Burmese scholars staying there, too, nice, clever boys. Their attitude towards Suu was totally different from other people, because of the respect in which they held her father.”

Yoshikazu Mikami, Suu’s first biographer, noted a similar effect. “In Japan she had her first encounter with Burmese students,” she wrote, “and they were all talking about the country in the same way—nostalgia, nationalism, respect for her father . . . She came to Japan to follow her father’s shadow—but then the image became clearer and became imbued with reality. And her sense of mission began to grow.”34

Noriko remembered one student in particular: In Japan he was nicknamed Koe-chan. “Koe-chan was one of the boys who respected her. Then he went home to Rangoon and at the airport he was surrounded by soldiers and they took a pistol out of his bag and he was sentenced to seven years in Insein Jail.

“He had a weapon illegally: That was the reason they gave.” But for Noriko and Suu it was ridiculous, unbelievable, scary. “Koe-chan was a serious student, he was studying classical Japanese literature. Firearms are totally banned in Japan—even we Japanese cannot obtain a pistol or any such thing in Japan, it’s totally illegal. So maybe a soldier put a pistol in his bag, to incriminate him.” The dark suspicion she and Suu shared was that the students at International House were being spied on by one of their number, and Koe-chan was punished for being friendly with Suu.

In Britain, Burma would always feel like a faraway, exotic country, its problems and realities having little bearing on everyday British life. But in Japan, the country which had maintained the closest diplomatic and commercial ties with Burma since independence, and which had been Ne Win’s most consistent sponsor, she was back in the same parish. There were Burmese spies here; more to the point, there were Burmese students who knew exactly who she was and why it mattered.

Noriko said,

She became aware of the mixture of respect and expectation with which they regarded her. Koe-chan was one of them. He was such a clever, promising boy. It’s quite difficult to get a PhD at Kyoto University. I think she felt some responsibility or guilt when she heard what happened to him. And her thinking about her life and her potential role began to change.

That is one of the reasons why she went into politics. It’s a very interesting coincidence: Aung San stayed in Japan, and Suu stayed in Japan, and both father and daughter went on to have the same experience, both had a revolution to fight. It’s a coincidence, isn’t it. But I really felt that that is what Suu was feeling.

At Christmas Michael and Alexander flew out to join Suu and Kim in Kyoto. Christmas is a non-event in Japan, but New Year is the biggest festival in the calendar, and on New Year’s Eve the whole family went out into the country to see their friends from Oxford.

“We took them to a nearby Buddhist temple where they all rang the big temple bell in the Japanese tradition called joya no kane,” Noriko remembered. “The next day I had a vivid insight into how much Suu missed Burma. I had heard of a temple not far away with a Burmese Buddha on the altar; I mentioned it to Suu and she asked if we could visit it. The gate was locked because of the holiday so I went round the back and asked for advice.”

A caretaker opened up the temple for them.

There on the altar was the Burmese Buddha with a gentle and delightful smile. Suu said “Ooooh!” then fell silent. Although she had always been very careful with money, she offered the priest 5,000 yen to say a prayer service, then prostrated herself on the earthen floor in front of the Buddha and went up and down any number of times, her hands together, chanting in Burmese.

It dawned on me that Suu and I had only known each other in England and Japan, never in Burma: I had only known her as a foreigner, with all that involves. Now, in a rustic village in Japan, coming face to face with a Burmese Buddha, suddenly she revealed her Burmese heart.

I had an intuitive feeling that she could only really fulfill herself in Burma. Would it be better for Suu to spend her whole life in comfortable Britain? Whatever the dangers and difficulties, would she not be happier immersing herself in her own country again?

Michael and Alex flew off, Kim went back to school and Suu resumed her research, but a seed had been planted. “One day towards the end of her stay in Japan she came to see me again, bringing some of our favorite manju cakes to eat with green tea,” Noriko recalled. Noriko was in the habit of speaking bluntly with her friend:

Over the tea I said to her, “Suu, if I were you, I would go back to Burma. Your country needs you. There are lots of things you could do there—your English ability alone would be very valuable. Michael could get a research job at some Indian university so you would not be far apart, you could put the children into boarding school . . . don’t you agree?”

Normally Suu was lightning quick with her replies, but now she merely stared down and said nothing. But I knew the answer.

Eventually Suu looked up. “Noriko, you’re right,” she said.

Two years later, for reasons that had nothing to do with politics, she found herself back there. And the rest of her life began to unfold.