AUNG SAN SUU KYI disappeared from view on May 30, 2003, the same day she had made the speech in Monywa, and reappeared nearly seven and a half years later, on November 13, 2010.

For most of that period her human contacts were restricted to the mother and daughter who now kept house for her, and her doctor who paid occasional visits. Every so often the UN’s latest envoy, a Nigerian called Ibrahim Gambari who was Under-Secretary General to Kofi Annan, was given permission to meet her; later, when she was charged with a criminal offence, she was given access to a lawyer, a colleague in her party.

But that was about all. She had no telephone line, let alone a computer with Internet access, no way of talking to her colleagues in the NLD, and she received no mail. As during previous periods of detention, her most important and valuable companion was the radio, which she listened to for many hours every day. But despite everything the BBC World Service and Voice of America could tell her, she emerged in November 2010 like Rip Van Winkle, amazed by the sight of ordinary Burmese talking into mobile phones—a device she had never used—dazzled by the profusion of Internet cafes in Rangoon, and tantalized by the possibilities offered by such unheard-of facilities as Facebook and Twitter.

Given the length of her latest spell of detention and the completeness of her isolation, it was surprising to hear her say, in one of her first post-liberation interviews, that it was not these years but her first years of house arrest—from 1989 to 1995—that were the worst. Perhaps she had simply grown used to the solitude, the simplicity, the regularity; the lake beyond the ragged garden shimmering in the sun; the monsoon rain dripping through the holes in the roof. “For some years,” she wrote in a column for the Mainichi Daily News after her release in 2010, “I had spent the monsoon months moving my bed, bowls, basins and buckets around my bedroom like pieces in an intricate game of chess, trying to catch the leaks and to prevent the mattress (and myself, if I happened to be on it) from getting soaked.”

The roof leaked because her estranged brother Aung San Oo had filed a court case in 2000 claiming that by rights half the house belonged to him—and blocking repairs on the basis that they would “damage” his property. The lawsuit dragged on until the last year of her detention, when, to the surprise of those who despaired of Burmese justice, the court found in her favor.

In her absence the years from 2004 to 2010 marked a great improve- ment in the regime’s luck, or its strategic skills, or perhaps both. Perhaps it was the purging of Khin Nyunt that made the difference: Always tugging against the will of his more conservative colleagues, he was the force behind Suu’s release both in 1995 and 2002, convinced that the only way to deal with Suu and her party was to incorporate them into the junta’s machinery rather than leaving them outside to make mischief.

Suu’s failed assassin Than Shwe felt no such compulsion. He had perhaps been persuaded that she could not, in fact, be done away with, but he was determined to lock her out of the country’s new political arrangements permanently. It took time and stolid determination to do so, but in the end the effort paid off.

At seventy-seven, the age Ne Win was in the crisis year of 1988, Than Shwe crowned his career with the engineering of a comprehensively rigged general election which left Suu and her party—not the “opposition” as so often described in the foreign press but the runaway winners of Burma’s only genuine election in modern times—out in the cold. He (or his clever advisers) then contrived to distract the world’s attention from his outrageous election scam by setting Suu free the following week. She emerged, to the jubilation of thousands of her supporters and the relief of the world, into a new landscape where she had no role. Is that the end of the story?

*

Democracy has had scant opportunity to sink roots in Burma’s soil. When Suu and her colleagues traveled around the country in 1989, one of her main tasks was to explain what this thing democracy was. She reported that people received it with great enthusiasm. Not surprising: Almost any political novelty would be preferable to the existing regime. But a generation of military dictatorship, which followed little more than a decade, and a chaotic decade at that, of democratic experiment, meant that Burmese democracy was very much a work-in-progress when Suu was put under house arrest for the first time. Since then the regime has done everything in its considerable power to kill it off.

If we try to assess Aung San Suu Kyi’s success and importance on the basis of the strength and the achievements of her party, therefore, we will come away with a poor result. Like the AFPFL, which her father headed, the NLD has always been more a “united front” than a party, a bundle of aspiring politicians with different ideas and backgrounds, bound together by the desire to end military rule and by belief in Suu and her charisma. It had little of the ideological glue that defines a party in much of the world, and but for her it would surely have broken into several warring factions long ago. After the watershed of July 20, 1989, when she was locked up for the first time, the junta declared open season on the party, jailing practically the entire top leadership; when it went on to win the election anyway, the persecution proceeded apace, with many MPs-elect in jail, many more in exile, and those that remained in the country living furtive existences. Similar persecution continued for the next twenty years, culminating in the de-registering—essentially the outlawing—of the party and the closure of all but one of its offices by 2007.

So to judge Suu on her success in implanting democracy in her country is to invite the retort: She has failed. An honorable failure, certainly, in the circumstances, but a pretty total one. The travesty of democracy on display in 2010’s election, with the largest party conjured into existence practically overnight by the simple device of taking the USDA and replacing the A with a P, shows how far democratic Burma has yet to travel.

But Suu’s impact on Burma is only partly reflected in the development, or lack of it, of democracy.

Her appeal to the people of Burma at the outset was nothing to do with her principles or democracy and everything to do with her name. Then there was her courage, the courage of this “pretty little thing” to defy the anger of Ne Win as no one had defied him for twenty-six years. There was her fragile beauty, and the charisma of all these things together. There was her commitment to nonviolence, about which she was adamant from the beginning, and her steady adoption—a little hazily at first, but gaining in confidence as she became an experienced meditator during her years of house arrest—of the Buddhist wisdom that has always underpinned Burma’s notions of morality, both private and public. Then, as the cord that bound all these qualities together, there was her steadfastness: her willingness to undergo bitter personal suffering for her cause, and her refusal, year after year, to give in.

This is why, of all the political figures to whom she has been compared, Gandhi is the only adequate comparison. A leader of the Indian National Congress, he was never contained by the conventional expectations of the political life, but burst those bonds time after time. He was a democrat inside the party, but he was seen by his millions of devotees as far more than a politician: as a sage, an embodiment of the Indian soul, and, in his clothing, his adoptive poverty and his devotion to the spinning wheel, as the apotheosis of the Indian peasant.

Suu is sometimes compared unfavorably with Gandhi in terms of strategic skill, and it may be true that nothing in her career matches the genius of his march to the Gujarati coast to make salt, in defiance of the Raj’s taxation laws. But the idea that it was Gandhi who forced the British out of India is a myth. By the time Britain pulled out—to a timetable dictated by postwar British austerity and the hostility to British imperialism of the United States quite as much as by the power of the Congress—Gandhi was already lamenting the failure of his movement to yield a united nation. The last decade and more of his life, as the independence movement he symbolized was finally producing results, was a succession of failures. Yet while he lived Gandhi incarnated not merely the democratic hopes of India but its pride, its courage, its community-transcending solidarity, its will to shake off centuries of tyranny and reinvent itself. Those achievements dwarfed his failures on the petty political plane.

Something very similar is true of Aung San Suu Kyi, and explains why, despite her absence from the scene from 2003 to 2010, and despite the near-death of the NLD during those years, her influence continued to be the single most important counterweight to the brutal might of the army.

During these years, Burma’s history consists of two parallel stories: the official one, which shows the steady and now almost unresisted consolidation of power by the SPDC; and the buried, underground history of the Burma which Suu represented and which like an underground stream was hidden from view most of the time, having no longer any legally permissible ways to show itself—but which then surged out, when the time was ripe, as an astonishing torrent.

*

The official story is best summarized in a series of dates. On May 30, 2003, as we have seen, Suu survived her assassination attempt but was taken into custody; she was later put in a purpose-built shack inside Insein Prison with a view of the gallows. She remained in jail for more than three months. In September it was rumored that she had gone on hunger strike—but it was untrue. She had been taken to hospital suffering from a gynecological complaint, which was operated on; there has been speculation that she had a hysterectomy. Afterwards she was not sent back to Insein but put in detention again in her home. The first photographs of her since her speech in Monywa in May 2003, taken with Ibrahim Gambari in November 2006—UN envoys had been refused visas for the previous two years—show her looking noticeably older, and very pale and thin.

Meanwhile the Seven-Point Road Map to Democracy announced in August 2003 was being put into effect. Khin Nyunt was now also in detention along with his family members, many of his subordinates were in jail, and his entire military intelligence apparatus had been dismantled. But where Than Shwe demonstrated great cunning was in retaining the road map even after he had sacked its architect. Without Khin Nyunt, and without Suu, it could still serve a useful purpose: In fact the absence of those troublemakers made it potentially much more useful to him.

The first requirement of the road map was for the National Convention to be reconvened, and so it came to pass, without the participation of the NLD. Almost unnoticed by the outside world with the exception of Beijing’s punctilious Xinhua News Service, the National Convention met several times: from December 2005 to the end of January 2006, from October to December of the same year, and from July to early September 2007. At each of these sessions, leaders of the regime-sponsored NUP and other regime-friendly politicians sat down with representatives of the ethnic “nations” on the borders which had cut ceasefire deals with the regime, and the SPDC’s bureaucrats coached them through the constitutional scheme they had concocted.

The result of their work, published in September 2007, was only the bare bones of a constitution, but its thrust was quite clear: to legalize and render permanent and indissoluble the preeminent power of the military over Burma’s political life. The constitution was put to the people in a referendum in May 2008, just as the poor farmers of the Irrawaddy Delta were struggling to recover from a cyclone in which more than 130,000 of them died. The referendum sailed through, thanks to strong-arm tactics at polling stations throughout the country, setting the scene for the nation’s long-delayed return to multiparty democracy—of a sort.

This constitutional cavalcade was interrupted in 2005 by the stunning news that the site on which builders had been working at a place called Pyinmana, four hours’ drive north of Rangoon, for the past few years was not another—or not just another—military cantonment but Myanmar’s new capital: Naypyidaw, “Abode of Kings,” located at the spot where Aung San, having switched sides, launched his offensive against the Japanese Army.

With a constitutional settlement under way, relative peace on the borders (though the army continued its war against the Karenni and the Shan, and its scorched earth policy against the Karen forced tens of thousands of Karen refugees into Thailand) and with the democrats well and truly gagged, the regime began to look more comfortable than it had in many years.

The much-ballyhooed Western sanctions were porous at best; the UN’s finger-wagging was so laughably ineffective that it could safely be ignored; the ongoing plundering of the country’s resources brought the dollars pouring in. And the regime had become adroit at playing its two giant neighbors, China and India, off against each other. Both were eager for minerals and for strategic regional advantage, and were happy to overlook almost anything to obtain them. India in particular, for a long time highly critical of the regime and its abuses, had learned to keep its mouth shut. “[The generals] are feeling feisty,” a Western diplomat told the Financial Times in May 2006. “They have never been in as comfortable a position internationally as they are today.”

*

There is, however, an alternative history of Burma during these years, an underground history.

One man whose career embodies that history is a small, feline Burmese monk called Asshin Issariya. He has taken the nickname, or nom de paix, of King Zero, because, he explains, Burma no longer has any rulers worthy of the name. I met him in the Thai border town of Mae Sot.

In this most traditional of Buddhist countries, the monks lost much of their central role as teachers after the British introduced secular education, but they retain vast importance as a moral force. According to Theravada belief, it is the devout life of the monk that helps the layman progress towards nirvana. The layman feeds the monk and the monk rewards the layman with merit. It is a symbiosis.

At his monastic university in Rangoon, Asshin Issariya learned to take the educational duties of the monk seriously. “My first teacher was very interested in politics,” he said. “This was a great advantage for me. As he always listened to the BBC, I could also hear it every day. In this way I learned about the situation of our country . . . I felt strongly that when I graduated I would need to do something strong for our country.”1

In 2000 he set up a small library in the university. In the same year he and some other monks went into the delta region where Suu had been blockaded during one of her attempts to travel into the countryside. “We went with the hope of being able to ask her advice about what we should do,” he said.

They were unable to meet her, but when they went back to Rangoon, Military Intelligence sent the university authority a report on their trip with a warning. “The university decided to close our library,” he said. “They said that if we continued to operate our library the regime would close the entire university. So I decided to leave the university because I could not run my library.”

But the library bug had bitten him. Not by chance, setting up a chain of public libraries was Suu’s dream before she became involved in politics. Anybody who seeks to change Burma soon runs up against the fact that the first thing to change is the level of ignorance. He said:

I left the university and moved the library to the village in Rangoon division where I was born and raised. I organized for a lot of people to read the books.

Then I went to Mandalay and met another monk at the Buddhist University there, and we started teaching English, Japanese, French and computers. We also opened three libraries in Mandalay as well as a library in the university. By 2004 we had opened a total of fourteen libraries, all in monks’ organizations. The library itself is open but within each library there is a section of political books that is kept secret.

While the National Convention slowly worked through its agenda, in the real world inhabited by the Burmese masses life was becoming harder than ever. In late 2006 the price of rice, eggs and cooking oil shot up by 30 to 40 percent. Burmese monks are closely in touch with the cost of living of the ordinary people: Tightening circumstances are soon reflected in the amount of food they receive in their alms bowls. So effective had been the terror tactics used by the regime in 1988 that very few people had dared to protest openly in the intervening years, and it had been around a decade since the last mass demonstrations. But so unacceptable were the price rises that in February 2007 a small protest against them was held in Rangoon. The authorities stamped on it hard, jailing nine of those involved.

Laymen knew they could anticipate swift and brutal repression when they took to the streets in protest, but the rules were different for monks: There is a powerful religious taboo against harming them. That is why King Zero and some of his brothers conceived the idea of a “peace walk”: not a conventional protest but a religious procession, consisting solely of monks, chanting sutras, “for the poor,” as he put it. “Two other monks and I from Mandalay and Yangon met secretly in Thailand to discuss how to do the peace walk and we planned it in detail, we told the foreign media about it. The idea was to do a peace walk because the people in our country are very poor,” he explained. “We put up stickers all over the cities.”

But the initiative was overtaken by events.

As we have seen, the final meeting of the National Convention was held from July to September 2007. It was the crowning session of a constitution-writing process that had begun fourteen years earlier. But in mid-August 2007, acting with the same arrogant dispatch as Ne Win when he demonetized high value banknotes in 1987, Than Shwe removed at a stroke the government subsidy from fuel. This caused the price of petrol and diesel to rise immediately by 66 percent, while the price of Compressed Natural Gas, used by buses, went up 500 percent in a week. Immediately the cost of travel went through the roof, adding another intolerable burden to the lives of the poor.

Protests against the cuts began in Rangoon on August 19th, led by a small group of activists, members of the “88 Generation Students,” those blooded in the events of that year, several of whom had recently been released from jail. Prominent was Min Ko Naing, the leader of Rangoon’s students nineteen years before. But repression was swift and violent, and thirteen of the protesters, including Min Ko Naing himself, were beaten and arrested. The regime was quick to suspect a revolutionary conspiracy behind this tiny protest. The civil unrest, according to the New Light of Myanmar, was “aimed at undermining peace and security of the State and disrupting the ongoing National Convention.”

On September 1st, King Zero and his colleagues met to discuss the situation. Four days later, a small demonstration in the town of Pakokku, on the Irrawaddy River near Pagan, which included monks, was broken up by troops; in the process some monks were beaten up and tied to trees and at least one disappeared. The next day young monks from the town took to the streets again and demanded that the regime apologize for the attack on their brothers, giving a deadline of September 17th.

No apology was forthcoming, so the Peace Walk, led by King Zero, U Gambira and others in the newly-formed All Burma Monks’ Alliance, began in earnest. First in Rangoon then in Mandalay and subsequently in other towns, the sangha began to walk through the streets, sometimes empty-handed, sometimes with their bowls turned upside down to indicate their repudiation of the military.

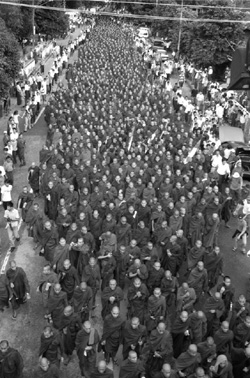

The processions began small but grew day by day: On September 24th the march in Rangoon consisted of 30,000 to 100,000 monks, making it much the largest show of popular strength since 1988. It stretched through the city for nearly a mile. To the extent that anybody had noticed it in the first place, the concluding session of the National Convention earlier in the month, the crowning triumph of Than Shwe’s rule, disappeared under this tsunami of indignation: the unprecedented sight—flashed around the world on satellite television—of tens of thousands of barefoot monks padding down Rangoon’s imperial boulevards in the driving rain.

Under the monsoon downpours they walked at the steady pace of Buddhist monks everywhere: neither pounding nor ambling, not marching in lockstep like soldiers but clearly a body of people, a corps on the move, saturated with rain, bare feet slapping on the slick tarmac.

If it was a political event it was of the most minimal kind: no banners, no slogans, no speeches, no protection, no masks, no helmets, no weapons. No shoes, even. They only carried flags, the multicolored flag of Buddhists.

Until the bloody days of the crackdown they faced no resistance: no police, not even one, no soldiers, not even a hint of control; just these irresistible human rivers swelling with endless new tributaries and streams. Marching, they chanted over and over the Metta Sutta:

Sukhino va khemino horitu, sabbasatta bhavantu sukhitatta, ye keci panabhutatthi, tasa va thavara va-navasesa; digha va ye va mahanta, majjhima rassaka anukathula . . .

“May all sentient beings be cheerful and endowed with a happy life,” they chanted. “Whatever breathing beings there may be, frail or firm, tall or stout, short or medium-sized, thin or fat, those which are seen and those unseen, those dwelling far off and near, those already born and those still seeking to become, may all beings be endowed with a happy life . . . As a mother protects her baby, her only child, even so towards all beings let us cultivate the boundless spirit of love . . .”

Everywhere they marched, the cameras of undercover Burmese video journalists, working for an independent Burmese news organization based in Norway, the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), captured them and the images went round the world.

In the West the mobilization of the monks was soon being called “the Saffron Revolution,” to be set alongside all the other “color” revolutions, Orange, Green and so on, that had changed the political face of Eastern Europe. But it made an uneasy fit: The monks had no banners, no apparent leaders, they shouted no slogans and made no speeches. They just chanted and walked.

Monks on the march in Rangoon, September 2007.

Ingrid Jordt, the American anthropologist and former Buddhist nun, was frustrated by Western misunderstandings of the phenomenon, misunderstandings which she feared could put the monks’ lives in danger.

I got a call from Seth Mydans of the New York Times who said, “I’m writing an article about the militant monks, I just need a few quotes from you.” I told him, you’re not going to get any because you’ve got it all wrong. If the New York Times writes that Burma has militant monks, then you have given carte blanche to the regime to crack down on those monks tomorrow, because that would mean they are playing politics. And he didn’t use that phrase in his piece, and the uprising went on for twenty days or something, because they couldn’t crack down on monks when they were just being moral admonishers.2

As the monks’ movement gathered momentum, I returned to the region to report it. At Mae Sot on the Thai border one refugee monk explained to me why monks take to the streets.

“To play a violent role would be far from our beliefs,” he said. “But we can have a mediating role. When Lord Buddha was alive he mediated between one particular king and the people who were rebelling against him, in a peaceful way. We monks are Buddha’s sons and so we try to follow in our father’s footsteps.”

In the same town I met Dr. Naing Aung, one of the student leaders in the uprising of 1988 who had fled into exile after the massacre that brought that rebellion to an end and who was still a leader of the democratic movement outside Burma. He explained to me what had changed between 1988 and 2007:

The big difference is that when we came out of Burma we were preparing for the armed struggle to overthrow the regime. We came out and began training to fight alongside the ethnic armies that were fighting the regime.

But now the protesters inside Burma are for the unarmed struggle. They want to win it by winning people’s hearts. It requires more courage because they are facing fully armed soldiers and they have no weapons. But they say, anyway we can’t compete against the army in armed power—but we can compete in terms of the support of the masses, in terms of truth and justice. They have been taking up Gandhian methods, what we call political defiance: demonstrations, boycotts, refusing to have religious communication with the regime . . .

The scenario sketched by Naing Aung was of a nation, estranged from its rulers for more than a generation, which far from giving up the struggle for freedom had discovered new resources for the fight in its traditional faith, and new ways to carry on that fight—of which the monks’ uprising was the first sign. And in choosing these means and this new nonviolent vanguard, people were also falling in with the woman for whose party they had voted in overwhelming numbers. Aung San Suu Kyi had written:

In Burma we look upon members of the sangha as teachers. Good teachers do not merely give scholarly sermons, they show us how we should conduct our daily lives . . . In my political work I have been strengthed by the teachings of members of the sangha . . . Keep in mind the hermit Sumedha, who sacrificed the possibility of early liberation for himself that he might save others from suffering. So must you be prepared to strive for as long as might be necessary to achieve good and justice . . . 3

The fact that the monks’ protest had erupted so soon after the conclusion of the National Convention may have been a coincidence, but it was instructive. Than Shwe had sought to correct one of Burma’s glaring anomalies, the fact that it lacked a national constitution and was ruled ad hoc by soldiers and emergency decrees. By this means he hoped to persuade his people, and the world, that Burma was back on a good course. But nothing he did could remedy the moral decay and corruption of which that anomaly was only one of many signs.

The climax of the uprising—captured only by a mobile phone camera—came on October 24th, when the barricades parted and one column of chanting monks was allowed to come almost to the gate of Suu’s home. Suu came out of the gate and saluted them with tears in her eyes as they continued chanting.

The crackdown began the next day: The regime threatened violence if the marches did not cease. Soldiers surrounded the Shwedagon, the mustering point for Rangoon’s marches, and on the night of September 26th began raiding monasteries, beating, arresting, forcibly defrocking and killing monks. When monks and members of the public defied the overnight repression to march again in Rangoon, troops opened fire, killing at least nine including Kenji Nagai, a Japanese video journalist, shot dead in cold blood. The murder was recorded by Democratic Voice of Burma’s brave undercover cameramen and the shocking images sent around the world.

A monk covers his eyes against smoke during the uprising.

“This popular uprising marked a new era in post-Independence Burmese politics,” says Jordt. “Burma had finally entered the age of information.” For the first time the Burmese people were able to see political reality—protest and violent repression—played out in real time on their televisions.

In an open-air coffee shop in the town of Kaw Thaung, in the far south of Burma, where I was reporting the uprising—the closest I could get to the action, Rangoon being under lockdown—one large television was tuned to a Japanese samurai drama, the other to CNN. During those days, much of the American channel’s news coverage was devoted to “the Saffron Revolution” with shots of tens of thousands of marching monks intercut with clashes on the streets, lorries full of troops and trashed monasteries. The customers in the coffee shop watched round-eyed and in silence.

According to Jordt, Than Shwe’s violent suppression of the protests, which millions of Burmese saw with their own eyes on television or the Internet, put him in a special category of vileness.

In suppressing the monks’ uprising, Than Shwe claimed in the state-run press that he was merely acting as a “good king” and punishing what he claimed were “bogus monks” who were betraying their cloth by turning political. “But that claim simply did not stand up in light of the images of monks being violently abused and beaten, of monks’ corpses floating in the rivers,” she said. “These were horrific images that shocked the devout nation of Buddhists. Than Shwe was seen as nothing more than a monk killer. The regime’s claim that these were only bogus monks was dismissed, as were the claims that the monks were playing politics.”

The Burmese were in no doubt, says Jordt: They expected any day that Than Shwe would “descend head first into the hell realms,” unless his astrologers and sorcerers were clever enough to come up with some black magic—yadaya in Burmese—to keep that fate at bay.4

Where did that leave Aung San Suu Kyi, locked up in her home throughout these events?

“She is seen as a witness, a moral compass for her country,” says Jordt. “Where she has the greatest traction is in her role as moral exemplar.” It is a role analogous to that of the monks: They shape the morality of individuals by exemplifying morally ideal behavior, while Aung San Suu Kyi plays a similar role in the political realm. “Her virtue-based politics . . . contrasts starkly with the ruling generals’ oppressive and cruel reign,” Jordt said.

Her power lies in being a witness to the process of moral degradation and violent oppression by the military regime. She inspires the populace to recall or imagine a different kind of social contract between ruler and ruled based on the highest human aspirations of compassion, loving-kindness, sympathetic joy and equanimity: the four sublime states of mind.

When the file of monks was permitted to walk down University Avenue and stop at the gate of her home, this performance evoked the way in which the sangha traditionally conferred its moral endorsement on an aspiring ruler, sanctifying their claim through recognizing their virtue.

She thereby became, to invoke a Burmese notion of political legitimacy, the “rightful pretender to the throne.”

The Burmese believe that evil acts provoke reactions in nature. Eight months after the violent suppression of the monks, in May 2008, the regime announced the referendum to endorse the new constitution that had been rubber-stamped by the National Convention—the fourth step on the road map. But days before the referendum could be held, a violent cyclone struck the country, killing 138,000 people, mostly poor farmers in the Irrawaddy Delta, rendering 2.4 million more homeless and causing billions of dollars in damage.

Jordt says that popular opinion in Burma was in no doubt that the disaster had been provoked by Than Shwe’s abuse of the monks. “Cyclone Nargis was taken as a sign that the regime was illegitimate and that the country was being punished as a whole for the rulers’ bad actions against the monks,” she said. “A little poem was secretly circulated through the population, encapsulating their dire expectations”:

Mandalay will be a pile of ashes

Rangoon will be a pile of trash

Naypyidaw will be a pile of bones.