i

Satureja hortensis • Savory

(Previously Calamintha hortensis)

FAMILY: Labiatae.

DESCRIPTION: Small herb with sparse foliage. Height: 1 foot (30 cm). Width: IV 2 feet (45 cm). Flowers: Pale lavender to white, sparse. Leaves: Dark green, on reddish stems, linear, to Vs inch (2.2 cm) long. Blooms: August to September.

HABITAT: The Mediterranean, introduced into southwest Asia and Africa.

CULTIVATION: Annual. Germination: 2 to 3 weeks. Space:

1 foot (30 cm). Soil Temperature: 68° F (20° C) at night and 86° F (30° C) during the day. Soil: Well drained, moist underneath, but dry on surface. pH: 7 to 8. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: By seed. It can become top-heavy as it matures and may need bracing. GARDEN DESIGN: Summer savory is not known for design qualities, but it has a wonderful aroma. It tends to look best planted in small patches. For low borders, plant winter savory. CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil (1.5%) includes carvacrol, cymene.

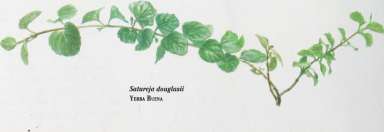

RELATED SPECIES: Winter savory (S. montana) is a perennial that sometimes replaces summer savory, although it is more pungent and not quite so tasty. Yerba buena (S. douglasii) was used by California Indians to relieve colic, purify the blood, reduce fevers, alleviate arthritis, and as a general tonic.

HISTORY: Called summer savory to distinguish it from its winter cousin, this herb has probably been cultivated since very ancient times. The Romans enjoyed satureja vinegar, and Virgil suggested planting the herb near bee hives to improve the honey. Perhaps he also considered the instant relief if offers when placed on bee and wasp stings. Italians cultivated it in the 9th century and claimed it had aphrodisiac properties. The English took the name savory from the French sauore.

CULINARY: Savory is found so often in pea and bean dishes that the Germans call it bohnenkraut, or “bean herb.” In recipes, it offers a lighter substitute for sage or a stronger version of mint. For a change of pace, substitute a .savory garnish in place of parsley or chervil. The essential oil is used commercially as a flavoring in salami and other foods.

MEDICINAL: Savory has been found to destroy bacteria and to reduce muscle spasms.' It also kills intestinal worms. Like many culinary herbs, it improves digestion and also relieves intestinal gas, probably one reason it is so popular with bean dishes. It also helps to eliminate lung congestion.

Marinated Savory Beans

Other beans, such as garbanzos, may be substituted.

2 cups (500 ml) green beans, cooked

2 tablespoons (30 ml) lemon juice V 2 cup (120 ml) vinegar

3 to 6 garlic cloves, whole

1 teaspoon (5 ml) savory

Combine ingredients and let sit at least I week. Drain and serve.

SCUTELLARIA LATERIFLORA

Scutellaria lateriflora • Skullcap

FAMILY: Labiatae.

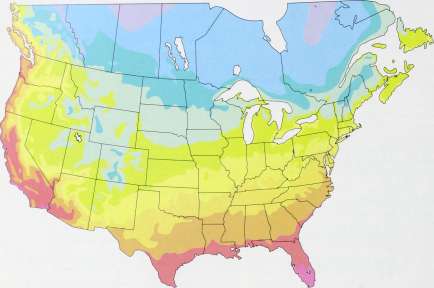

DESCRIPTION : Height: 1 to 2 feet (30 to 60 cm). Width; 8 inches (20 cm). Flowers: Small, blue, in clusters on upper areas of stems, about Vs inch (8 mm) long. Leaves: Thin, almost oval coming to a sharp point, toothed around the edge. Blooms; July to September. HABITAT: United States, Newfoundland to British Columbia and south to Georgia, and California, in wet places. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 4 to 5. Germination: 3 to 4 weeks. Space; 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 cm). Soil Temperature: 60° to 70° F (15° to 21° C). Soil: Moist. pH: 6 to 8. Sun; Partial shade. Propagation; By seed or by root division. It spreads on its own, but not too quickly and can be easily contained.

GARDEN DESIGN: A small plant that easily fades into the background, skullcap can be highlighted by growing it in a patch enclosed by stones or in a raised bed. It does well in a pot, provided the soil stays moist.

CONSTITUENTS: Flavonoid glycosides (scultellonin, scutel-larinan), essential oil.

RELATED SPECIES: A number of species, including S. galeri-culata and S. minor, both native to Europe, have similar properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, S. baicalensis is a sedative that relieves muscle and rheumatism pains, lowers fever, expels tapeworms, and corrects some heart conditions. True skullcap is dried to very little weight and is often substituted in the United States with the heavier and more abundant germander {Teucrium species). HISTORY: Skullcap was such a well-known remedy for rabies, it was once even called “mad-dog weed.” This property was discovered by Dr. Lawrence Van Deveer in 1773, although his claim was never substantiated. Rafinesque, in his 1830 Medical Flora, said that his use of the herb “prevented 400 persons and 1,000 cattle from becoming hydrophobic.” It found its way into many 19th century patent medicines as a nerve tonic, especially for “female weakness,” and as an epilepsy “cure.”

MEDICINAL: Skullcap leaves are used mostly for their actions on the nervous system: They help relieve anxiety, depression, insomnia, nervous headache, nervous twitches, muscle cramps, and convulsions. The Eclectic doctors of the nineteenth century found skullcap helpful in cases of nervousness due to emotional stress or physical exhaustion and used it as a bitter to stimulate digestion. Although few scientific studies have been performed on this species, it is likely that it possesses many of the medicinal properties found in similar species. Most of the research that has been done comes from Russia, where studies support many claims of skullcap’s usefulness as a sedative and stabilizer of stress-related heart disease.' Those studies also discovered that it lowers blood pressure and cholesterol. Native Americans did use skullcap to treat heart disease, as well as to promote afterbirth and menstruation. Herbalist Michael Tierra has found skullcap helpful in combating drug and alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Clinical tests with S. baicalensis in China found it improved symptoms in over 70% of patients with chronic hepatitis, increasing appetite, improving liver function, and reducing swelling.^ Other studies show it reduces inflammation and allergic reactions.

CONSIDERATIONS: Very large doses are said to cause dizziness, erratic pulse, and mental confusion.

OTHER: Skullcap is used in homeopathy.

Senecio cineraria • Dusty Miller

(Previously Cineraria maritima and Centaurea maritima ‘Diamond’)

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION : Silver, woolly white herb. Height: 2 V 2 feet (75 cm). Width; 1 foot (30 cm). Flowers: Yellow or cream, V 2 inch (1.25 cm) across, 12 to a bunch. Leaves: 6 inches (15 cm) long, thick, woolly with dense white hairs underneath, in 10 to 12 segments so divided, they appear to be individual leaves. Blooms: July to September.

HABITAT: The Mediterranean.

CULTIVA TION: Perennial. Zone: 6. Germination: 10 to 15 days. Space: 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm). Soil Temperature: 65° to 70° F (18° to21° C). Soil: Light and well drained. pH; 7 to 8. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: By cuttings, layering, or seeds. Start seeds in early spring or 8 to 10 weeks before last frost.

GARDEN DESIGN: This silver-gray plant is very popular in herb gardens, where it stands out with its contrasting color and leaf

texture. Keeping flowers cut off encourages more foliage and keeps the plant from looking leggy.

CONSTITUENTS: Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (jacobine, jacodine, senecionine).

RELATED SPECIES: The ornamental S. viro-vira has more finely cut foliage and no ray petals on the flowers. S. cineraria ‘Dwarf Silver’ is a short, 9-inch (22.5-cm) version with leaves even more divided'. Life root (S. aureus) is still an ingredient in Lydia Pinkam’s women’s herbal formula for genitourinary problems. HISTORY: Cineraria means “’ashy gray,” the coloring that also gives this herb the common name of “dusty.” The color was also said to resemble the dusty white wings of the miller moth. (The miller moth itself was named after the dusty clothing worn by grain millers in previous centuries.)

MEDICINAL: Sterilized plant juice has been used for eye drops for capsular and lenticular cataracts.

CONSIDERATIONS: Dusty miller and the other species mentioned all contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which are presently under scientific scrutiny for .safety.'

Senecio cineraria Dusty Miller

S / L Y B U M M A R I A N U M

Silybum marianum • Milk Thistle

(Previously Carduus marianus)

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION : Wide, bristly plant —obviously a thistle. Height: To 4 feet (1.2 m). Width; 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Flowers: Bristly tight cup, deep purple, 2 inches (5 cm) across. Leaves; Large, 2'/2 feet by 1 foot (75 cm by 30 cm), glossy, thick, marbled with white veinlike patterns, prickly edges. Fruit: Oval, smooth, mottled with brown. Blooms: June to September.

HABITAT: The Mediterranean, naturalized as a weed on the West Coast of the United States, in dry, rocky areas,wastelands, and fields. Naturalized in Australia and on various noxious weed lists. CULTIVATION: Annual or biennial. Germination: 10 to 15 days. Space: 3 feet (90 cm). Soil Temperature; 65° to 75° F (18° to 24° C). Soil: Well drained, dry, very drought tolerant. pH; 6-8. Sun; Full sun. Propagation: By seed. Since it reproduces by seed, it is easy to keep under control in a garden setting.

GARDEN DESIGN: If you know this thistle as a weed, you may question putting it in your herb garden, yet its attractive, mottled leaves are very interesting and stand out beside other herbs. CONSTITUENTS: Seeds: essential oil, flavolignans called silymarine, such as silybin.

RELATED SPECIES: Also known as variegated thistle and Our Lady’s Thistle. Not closely related to holy or blessed thistle (Cnicus benedictus), although they are often confused with each other. HISTORY: Early Christian tradition dedicated milk thistle to Mary, calling it Marian thistle. It was considered interchangeable

with blessed thistle (Cnicus benedictus). Long before research was done on the herb, it was suggested as a bitter digestive, liver tonic, and poison antidote. German physician Rademacher reported success in giving it to his liver patients in the early 19th century. CULINARY: Dioscorides suggested eating silybon “sodden with oil and salt,” which would probably hide the taste of anything. Actually, the steamed leaves are quite tasty, providing the prickly edges have been cut off! The young stalks were once widely cultivated as a vegetable, and their taste was considered superior to that of cabbage in the 18th century. The seeds, with a slightly bitter nutty flavor, can be ground and sprinkled on food.

MEDICINAL: Milk thistle has been proven to protect the liver from damage—even against the deadly deathcap mushroom (Arnacitaphalloides), which contains some of the most potent liver toxins known. When silybin, a constituent from milk thistle, was injected into human patients up to 48 hours after they accidentally ingested deathcap, it prevented the normally anticipated fatalities.' Many commercial preparations are manufactured in Germany from the seeds. An official Tinctura Cardni Marine Rademacher is still listed in the pharmacopoeias of some countries. The latest research will probably reestablish milk thistle’s place as a medicine, at least in some synthesized version. Clinical studies show that symptoms of acute hepatitis, especially digestive problems, improved within 2 weeks of taking milk thistle. Well-being and appetite also improved. It also has successfully treated patients with chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver.^ The detrimental effects of jaundice, drugs, environmental toxins, and alcohol on the liver may be countered with milk thistle. More information can be found in Milk Thistle: The Liver Herb by Christopher Hobbs (Botanica Press, 1985).

s

S T A C H Y S BYZANTINA

i

S T A C H Y S OFFICINALIS

Stachys byzantina • Lamb’s Ears

(Previously S. lanata, S. olympica)

FAMILY: Labiatae.

DESCRIPTION: Erect, furry leaves. Height; To 3 feet (90 cm). Width: 1 foot (30 cm). Flowers: Purple or pink, to 1 inch (2.5 cm), running along furry, white, 12-inch (30-cm) stalks. Leaves: Thick, long, very soft and covered with woolly, white hairs. Blooms: May to June.

HA BIT A T: Turkey, southwest Asia.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone; 2 to 3. Germination; 1 to 2 weeks. Space; 8 to 15 inches (20 to 38 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° F (21° C). Soil: Fairly rich, well drained, but tolerates poor conditions. pH; 7.5 to 8.5. Sun: Full sun, or partial shade. Propagation; By seed or divide root clumps. It spreads easily on its own.

GARDEN DESIGN: The soft, gray leaves of lamb’s ears provide excellent contrasts in any garden. It is a favorite plant of children so be sure to place it where they can easily feel its furry leaves. It forms an ornamental groundcover that is ideal for lining the edges of pathways.

CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil, tannin.

RELATED SPECIES: Related to betony (IS. o7//'c/no//s/ HISTORY: The exceptionally fuzzy leaves gave it the names lamb’s ears and woolly betony.

CULINARY: Lamb’s ears make a light-tasting tea. The leaves can be steamed and eaten, although some people find their fuzziness unappealing.

MEDICINAL: Also called woundwort, lamb’s ears makes a natural bandage and dressing to staunch bleeding.

Stachys officinalis • Wood Betony

(Previously S. betonica, Betonica officinalis)

FAMILY: Labiatae.

DESCRIPTION: Softly textured bush. Height: 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Width; 2 feet (60 cm). Flowers: Bright blue, V 4 inch (6 mm), arranged in whorls on the top of the spikes. Leaves: A rosette of stiff, slightly hairy, pointed leaves, about 5 inches (12.5 cm) long. Blooms: July to August.

HA BITA T: A European native that has naturalized itself in many parts of the world.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 4. Germination; 15 to 20 days. Space: 14 to 18 inches (35 to 45 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° F (21° C). Soil: Well drained, dry. pH: 6.5 to 7.5. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: Easily grown from seed or divided by prying apart the thick clumps, or by cuttings.

GARDEN DESIGN: A well-contained herb that can be used as a high border or set near the back of the bed. It is most noticeable when flowering, since the vivid blue flowers are highlighted against pinks, grays, and greens.

CONSTITUENTS: Tannins (to 15%), saponines, glucosides, alkaloids (bettonicine, stachydrine, trigonelline).

RELATED SPECIES: Lamb’s ears, or woolly betony (5. byzan-tina), a very attractive herb with furry white leaves, is a children’s favorite. It is perfect for rock gardens or as a groundcover. A white betony (S. officinalis ‘Alba’J has white instead of blue flowers. This

betony is not related to the wood betonys (Pedicularis species) or lousewort (P. syluatica), which is also a headache remedy. HISTORY: An old Italian proverb indicated this herb’s value when it declared, “Sell your coat and buy betony.” The Spanish agreed, complimenting each other with the phrase, “He has as many virtues as betony.” Betony was also appreciated by the ancient Greeks, the Romans, and the Anglo-Saxons, who discussed it in their 11th century Lacnunga. A treatise written by Antonius Musa, physician to Emperor Augustus, listed 47 diseases that could be helped by betonica. The name was derived from vettonica, from the Vettones, an ancient people inhabiting the Iberian peninsula. MEDICINAL: Betony, which means “head herb,” was a traditional remedy for problems associated with the head; the Medicina Britannica of 1666 states, “I have known obstinate headaches cured by daily breakfasting for a month or six weeks on a decoction of Betony.” It was also used to treat giddiness, dizziness, and hearing difficulties. The British traditionally relieved headaches by snuffing or smoking betony leaves combined with eyebright and coltsfoot in the famous “Rowley’s British Herb Snuff.” The French recommended the leaves of beteine for lung, liver, gallbladder, and spleen problems. One of its constituents, trigonelline, also found in fenugreek, has been shown to lower blood sugar levels. Betony was appropriately known as woundwort, since applied externally it stops bleeding, promotes healing, and draws out boils and splinters.

OTHER: A dark yellow dye can be extracted from betony. It makes an attractive cut flower, as well.

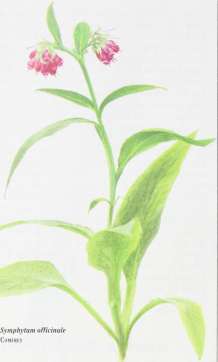

Symphytum officinale • Comfrey

FAMILY: Boraginaceae.

DESCRIPTION: Densely growing patches of leaves. Height: 3 feet (90 cm). Width: 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Flowers: Purple-pink, hanging in bell-like clusters from the tips of the stems. Leaves: Tall, rigid and very prickly to the touch, to 1 foot (30 cm) tall, 5 inches (12.5 cm) wide, on hollow, bristly stems. Roots: Thick, fleshy roots that can trail 6 feet (1.8 m). Blooms: April to September.

HA BITA T: Most of the 25 or so species are native to Europe and Asia, but comfrey has naturalized itself elsewhere, including parts of the United States, mostly in rich, wet meadows and ditches. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 3. Space: 2 feet (60 cm). Soil: Moist, fairly rich. Sun; Full sun to partial shade. Propagation: Comfrey propagates so readily from even the smallest piece of root, that it is rarely grown from seed, and often does not produce seed. Repeated cuttings can produce 4 to 10 harvests of comfrey in one season.

GARDEN DESIGN: Comfrey is difficult to eradicate once established. If you want to include comfrey in a small garden, plant it in a submerged barrel or pot with drainage holes in the bottom. CONSTITUENTS: Mucilage, allantoin, protein (to 35%), alkaloids (including pyrrolizidine), sterols, zinc, tannic acid, asparagine, vitamin B 12 .

RELATED SPECIES: Russian comfrey (S. x uplandicum) has been considered superior, but does contain more pyrrolizide alkaloids. It has been used very little in Russian folk medicine. S. officinale ‘Variegatum’ has white-rimmed leaves.

SYMPHYTUM OFFICINALE

i

HISTORY: The name comfrey comes from the Latin con firma, “with strength,’’ and Symphytum is derived from the Greek symphy-tos, “to unite.” It is also popularly called knitbone. The gummy root, when spread on muslin and wrapped around a sprain, torn ligament, or broken bone that has been set, stiffens into a cast. Squires in The Companion to the 17th-century British Pharmacopoeia, 1916, describes a bonesetter who used comfrey in this manner. A few avid Englishmen began promoting comfrey as fodder in the late 19th century. Henry Doubleday first used comfrey to substitute for the difficult-to-obtain stamp glue known as gum arabic. CULINARY: The leaves, steamed like a vegetable, lose their prickly texture and can be eaten, but read “Considerations” first. MEDICINAL: Comfrey leaves and especially the root contain allantoin, a cell proliferant that increases the healing of wounds. It also stops bleeding, is soothing, and is certainly the most popular ingredient in herbal skin salves for wounds, inflammation, rashes, varicose veins, hemorrhoids, and just about any skin problem. Taken internally, comfrey repairs the digestive tract lining, helping to heal peptic and duodenal ulcers and colitis (inflammation of the colon). Studies show it inhibits prostaglandins, which cause inflammation of the stomach lining.' Comfrey has been used to treat a variety of respiratory diseases, and is a specific when these involve coughing of blood.

CONSIDERATIONS: Investigations on pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA) have found over 200 types occurring in about 3 % of the world’s

plants, including comfrey. In one study, rats fed a comfrey diet (up to 33%) developed liver cancer. The isolated symphytine, one of 8 pyrrolizidine alkaloids identified, was also found to produce liver cell tumors in rats.^ So far, only two cases of possible comfrey poisoning have been reported in people. One was a 13-year-old British boy who ate comfrey regularly for about 3 years, but the researchers admitted that he “may have been more susceptible . . . because of his underlying inflammatory bowel disease.” They also stated. These alkaloids are less toxic than those in other plants—for example Senecios—which may explain why only a few cases of hepatic veno-occlusive disease caused by ingestion of comfrey are known.” Scientists assume that applying comfrey externally, as in poultices and salves, is perfectly safe. As far as internal use goes, the fresh root contains approximately 10 times more PA than fresh leaves.^ Fresh, young, spring leaves average .22% PA, young fall leaves have .05% PA, mature leaves have only .003% PA, and two investigations did not detect PA at all in dried leaves.' It is interesting that water extracts of the whole leaves actually decreased tumor growth and increased survival time in cancer patients.® The Ames test for toxicity showed comfrey produced le.ss mutants than the control, suggesting it may have anticancer activity. Some reports on comfrey’s toxicity have resulted from a mistaken identification of the poisonous foxglove—the leaves of which resemble comfrey. A complete modern history is found in Comfrey: Fodder, Food, and Remedy by Lawrence D. Hills (New York: Universe Books, 1976). OTHER: Comfrey is a rich addition to the compost pile.

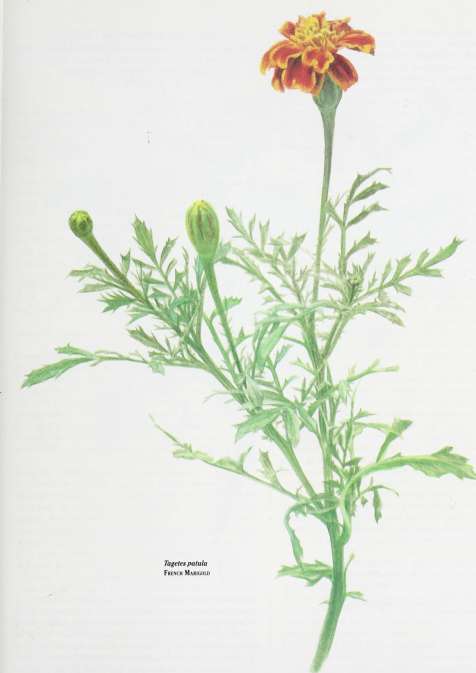

Tagetes patula • French Marigold

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION: A densely compact annual producing many flowers. Height: 2 feet (60 cm). Width: 1 foot (30 cm). Flowers: Various combinations of orange, yellow, red-brown, 2'/2 inches (6.25 cm) across. Leaves: Divided with ragged edges. Blooms: July to August.

HABITAT: Mexico.

CULTIVATION: Annual. Germination: 5 to 7 days. Space: 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° to 75° F (21° to 24° C). Soil: Dry, well drained, fair—too rich a soil produces more foliage and less flowers. pH: 4 to 6. Sun: Full sun, open location. Propagation: Very easy to cultivate by seed. In cold climates, start indoors 6 to 8 weeks before the last frost. In warmer areas, sow from midsummer through autumn to avoid hottest weather during flowering, or any frost. Picking the flowers increases the bloom. GARDEN DESIGN: Single-petaled forms are the most popular. The abundant flowers and long blooming season make French marigolds perfect for filling in empty spots. They make a low, easily controlled, and colorful hedge.

CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil includes limonene, carvone, citral, camphene; valeric acids, salicylaldehyde, tagetones. RELATED SPECIES: Many flower sizes and colors in various cultivars; most have an extended flowering season, and some resist heat better. They are often confused with pot marigold (Calendula officinalis). Tangerine gem’ (7? tenuifolia cultivar) has distinctly lemon-scented leaves. There is also an orange-scented marigold {T. tenuifolia ‘Pumila’).

T A G E T E S P A T U L A

T A G E r E S P A T U L A

t

HISTORY: Early Mexicans fed marigold petals to chickens to color their skin and to brighten their eggs. For centuries, long before the term ‘companion planting” was coined, the South American Incas interplanted marigolds with their potatoes to reduce insect damage. According to Robert Sweet, in his Hortus Bri-tannicus{\S26), the marigold arrived in Europe in the 16th century. Thinking they came from India, the botanist Pierandrea Mattioli designated them Caryophyllus indicus, ‘‘a clove pink from India.” They were in high fashion in both Europe and the United States throughout the 19th century and still find a place in flower, vegetable, and herb gardens. In Holland, they are still interplanted with roses as an insect repellent.

CU LIN ARY: The oil is a food flavoring in frozen dairy des.serts, baked goods, gelatins, puddings, relishes, and some alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages.

MEDICINAL: Marigold flowers were an Aztec remedy for coughs and dysentery (probably T. erecta). Various species, especially T. minuta, have also been used to lower blood pressure, as a tranquilizer, to dilate the bronchials, and to reduce inflammation. The leaves were placed on skin sores and made into a wash for inflamed eyes. The Chinese find T. erecta useful in treating whooping cough, mumps, and colds. South Americans use various species to eliminate intestinal parasites and colic. The polyacetylenes in French marigolds have displayed some anticancer properties. CONSIDERATIONS: Some people get a contact skin dermatitis from touching marigolds.

OTHER: Researchers at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, found that French marigolds actually attack some insects. The polyacetylenes they contain excite surrounding oxygen when activated by light every time a munching insect breaks the leaf cells. Scars have actually been found on insects the plant has attacked. Marigolds also inhibit the ability of some insects to detect surrounding vegetables, and they deter white flies; T. minuta even kills surrounding weeds. Naturalized in Australia, this species is known as stinking Roger. In studies at the University of California, San Jose, French marigold greatly reduced cabbage worm eggs and larvae and worm damage, although 4 plants were required in every 14-square-inch (90-square-cm) plot! The only problem is that crop yields were also reduced. The roots exude a substance that deters nematodes, destructive microinsects found in soil. Scientists also found that a diluted tea of the flowers is lethal to mosquito larvae.' French marigold flowers look great and are long-lasting, although their strong smell has kept them from being placed in vases as often as other species. The rich marigold color also is u.sed in potpourri and produces a yellow dye on silk and wool.

As for marigolds, poppies, hollyhocks, and valorous sunflowers, we shall never have a garden without them, both for their own sake, and for the sake of old-fashioned folks, who used to love them.

— ''Star Papkrs" A Discourse m Flowers. HE^RY Ward Beecher ( 1813 1878 ), American

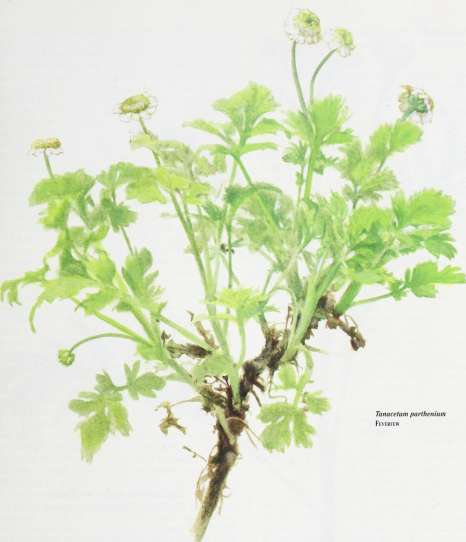

Tanacetum parthenium • Feverfew

(Although listed as Chrysanthemum parthenium in Hortus Third, the newest name is welLestablished. Previously Pyrethrum parthenium and Matricaria parthenoides,

M. capensis, M. eximia)

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION : Small, bushy herb, strongly scented. Height: To 4 feet (1.2 m). Width: 2 feet (60 cm). Flowers: Daisylike, with white petals and raised yellow centers, 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter, clustered together with up to 30 heads. Leaves: Yellow-green, divided, flexible, shaped like miniature oak leaves, 3 inches (7.5 cm). Blooms: June to August.

HABITAT: Native to southeast Europe; introduced elsewhere. Brought to America as an ornamental, it proceeded to make itself at home. Cultivated commercially in Japan, Kenya, South Africa, and parts of central Europe.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 4. Germination: 10 to 14 days. Light improves germination. Space: 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° F (21° C). Soil: Well drained, average. pH: 5 to 7.5. Sun: Full sun or partial shade. Propagation: By seed or by cuttings (taken with the heel of the plant intact).

GARDEN DESIGN: The small, white flowers show up especially well against dark green plants like betony or next to a fence. CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil, sesquiterpene lactones (par-thenolide, santamarine).

RELATED SPECIES: A golden-leaved feverfew (T. parthenium ‘Aureum’) is available.

HISTORY: Feverfew has experienced a botanical-name identity crisis. The Greeks called it pyrethron, probably from pyro, meaning “fire,” descriptive of its taste. This became pyrethrum to the Romans. Feverfew was first designated botanically as Matricaria as a close relative of chamomile—an herb for which it is often mistaken. Since then, it has joined forces with the chrysanthemums and the pyrethrums and now shares the genus with tansy. Old England knew it as featherfew. While the common name feverfew, from the latin febri, or “fever,” represents one of its possible uses, herbalists rarely use it to reduce fevers.

CULINARY: Feverfew has been added to food to cut the greasy taste but is extremely bitter and disagreeable to most palates. MEDICINAL: Feverfew is gaining fame for its ability to alleviate migraine headaches. It is not a new idea. John Hill, in The Family Herbal, stated in 1772, “In the worst headache this herb exceeds whatever else is known.” Clinical studies at the Department of Medicine and Haematology at City Hospital in Nottingham, England, had 20 headache patients eat fresh feverfew leaves (.9 grain, or 60 mg) daily for 3 months and stop using headache-related drugs during the last month. After they were given capsules of .37 grains (25 mg) of freeze-dried leaf every day, they experienced less severe headaches and fewer symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, than a placebo group. As an added benefit, their blood pressure went down from an average of to ’^V 82 in six months. Some even described a renewed sense of well-being.' Perhaps Gerard was onto something in the 17th century when he suggested feverfew “for them that are giddie in the head . . . melancholike, sad, pensive.” Another, double-blind study saw a reduction of migraine headaches, as well as nausea, by 24 % in 72 volunteers." E. S. John-

TANACETUM PARTHENIUM

son, a feverfew researcher and author of Feverfew, A Traditional Herbal Remedy for Migraine and Arthritis (Sheldon Press, 1984), speculates that feverfew can help not only migraine, but premenstrual and menstrual headaches, as well as diseases caused by chronic inflammation, such as arthritis. It is hypothesized that feverfew prevents blood vessel spasms in the head by inhibiting amines, including serotonin, certain prostaglandins, and histamine that create inflammation and constrict blood vessels, which

may contribute to headaches, it may be more active than other nonsteroid, antiinflammatories, such as aspirin. For instance, it has not been shown to inhibit blood clotting.^ While many herbalists feel the fresh leaves, or an extract made from them, are preferred, results have been seen with fresh, freeze-dried, and air-dried leaves, although boiling feverfew tea for 10 minutes instead of steeping it did reduce its activity in one study. CONSIDERATIONS: Problems such as mouth ulcers and soreness and occasional digestive disturbances have been reported in about 18% of those using feverfew on a regular basis."'

OTHER: Feverfew is a moth repellent.

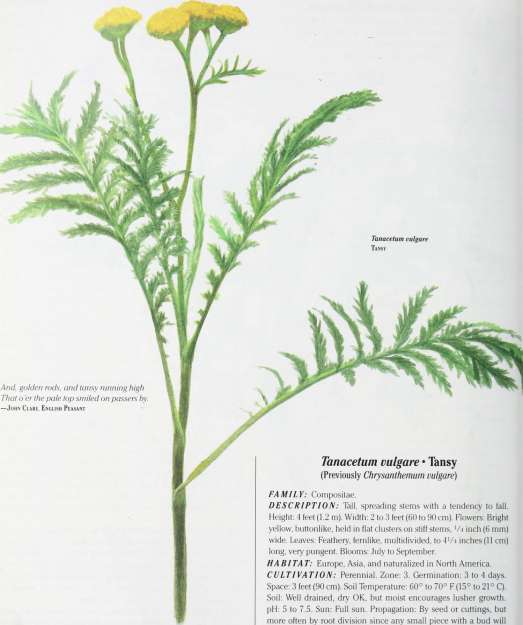

TAN A C E T U M V U L G A R E

*

Tanacetum vulgare Tansy

Tanacetum vulgare • Tansy

(Previously Chrysanthemum vulgare)

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION: Tall, spreading stems with a tendency to fall. Height: 4 feet (1.2 m). Width: 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Flowers: Bright yellow, buttonlike, held in flat clusters on stiff stems, V 4 inch (6 mm) wide. Leaves: Feathery, fernlike, multidivided, to 4'/4 inches (11 cm) long, very pungent. Blooms: July to September.

HA BITA T: Europe, Asia, and naturalized in North America. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 3. Germination: 3 to 4 days. Space: 3 feet (90 cm). Soil Temperature: 60° to 70° F (15° to 21° C). Soil: Well drained, dry OK, but moist encourages lusher growth. pH: 5 to 7.5. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: By seed or cuttings, but more often by root division since any small piece with a bud will gladly sprout.

And, golden rods, and tansy running high That o ’er the pale top smiled on passers by. —John Clare, English Peasant

TARAXACUM OFFICINALE

GARDEN DESIGN: Gardeners who prefer a trim garden tend not to appreciate tansy’s haphazard nature. It flops on plants next to it and spreads rapidly. It is helpful in restricted situations to keep the flower stalks under control by tying them together. I’ve found the best location is out of the main herb garden, as a border along a lawn, large path, or driveway, where it can be contained. CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil (from .12% to .18%) includes thujone (to 70%), borneol; glycosides; sesquiterpene lactones; terpenoids (pyrethrins), vitamin C; citric and oxalic acids. RELATED SPECIES: Curly leaf tansy ("Z" nu/gare var. cr/spum) with its finely cut, luxuriant foliage is more ornamental and easier to contain, although some curly forms don’t produce flowers. Botanists think that tansy has a number of subgroups, or races, distinguished by their different essential oil compositions. Tansy or common ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) is an unrelated European native with similar leaves that is considered a troublesome weed and poisonous to cattle in the United States, especially in Oregon, and in Australia, where it is considered a noxious weed. HISTORY: A Greek legend tells of a beautiful young man, Ganymede, who was given a tansy drink to make him immortal, so he could serve Zeus. The Greeks called it athanasia, or “immortality,” because, according to 16th-century herbalist Dodoen, the flower lasts so long. It became the Spanish atanasia, then the French tanaisie, and finally the English tansie. A favorite herb of Emperor Charlemagne, it was planted in all his monasteries. The monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland has grown it for over 1,000 years. CULINARY: In 1677, John Evelyn described eating a hot dish of young tansy leaves stir-fried with orange juice and sugar as “most agreeable.” Tansy was added to omelets and garnished other dishes. Elizabethan “tansies” were puddings flavored with the fresh herb that were purposely made with the bitter herb during Lent to offset the taste of salted fish. Chances are that tansy was eaten as a spring bitter long before Lent existed. William Coles, in 1656, wrote that it counteracted “the moist and cold constitution winter has made on people ...” The Irish in County Cork sometimes still use tansy to flavor their drisheens. In Scotland, the roots have been preserved in honey or sugar and eaten for gout. Some alcoholic beverages are still flavored with tansy, including Chartreuse, although it must be with a thujone-free extract. MEDICINAL: As Gerard said in the 16th century, tansy “be pleasant in taste and good for the stomache.” The constituent thujone kills intestinal roundworms and threadworms, scabies, and heals other infected skin conditions. Very small doses have been used to treat epilepsy and to encourage menstruation. CONSIDERATIONS: Tansy contains thujone, which is also found in wormwood. Potentially harmful to the central nervous system, an overdose can produce seizures. Don’t eat much tansy, and none if pregnant.

OTHER: Tansy deters ants (which means they walk around it instead of over it), fleas, and moths. Thomas Tusser, in his 1557 Strewing Herbs of All Sorts, described it as one of the best flea repellents. It was also rubbed over meat to keep flies away. A strong tansy tea repels several beetles, including the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata), according to studies for Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. The leaves dye wood green and the flowers are excellent in dried flower arrangements and wreaths.

Taraxacum officinale • Dandelion

(Previously T leontodon and L. taraxacum)

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION : Compact, low-growing plant. Height: IV 2 feet (45 cm). Width: 2 feet (60 cm). Flowers: 1 bright yellow, sun-ray flower on a hollow stem. Opens with morning sun and closes in the evening. Leaves: Long, to 1 foot (30 cm), pliable, deeply toothed, growing from a central rosette. Fruit: White tufted globes, which are easily blown by the wind or children. Root: Fleshy taproot, brown with a milky, sap-filled core. Often 1 foot (30 cm) long and V 2 inch (1.25 cm) in diameter. Blooms: April to June.

HABITA T: A European and Asian native, dandelion has needed no encouragement to take up housekeeping elsewhere and has done so throughout North America and Australia. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 3. Germination: Varies greatly. Space: 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm). Soil Temperature: 55° to 60° F (13° to 15° C). Soil: Not fussy! Prefers nitrogen-rich, slightly damp. pH: 4.2 to 8.2. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: Most people are more concerned about getting rid of dandelions than planting them, but they do grow sweeter leaves and roots when cultivated, and there is a large-leafed form sold for eating. Seeds sown in the autumn provide early spring greens. When growing dandelion for fancy salads, protect the plant’s leaves from sunlight so they blanch like chicory leaves, for a pale, less bitter flavor. Collect the roots in the autumn or early spring. Autumn-harvested roots have been the official herb used for medicine since they contain more bitters and inulin and have been considered more medicinal, although according to the British Pharmacopoeia, spring roots are less bitter and contain more taraxacin. The laevulose and sugar convert to inulin during the growing season, so fall extracts contain less sweetness and more sediment. Frost decreases the root’s properties. Old roots become leathery, twisted, and very bitter.

GARDEN DESIGN: If there are dandelions in your garden, you might as well make them prominent so visitors won’t think you simply forgot to weed. Just explain that weeds are defined as plants you don’f want!

CONSTITUENTS: Roots:taraxacin,triterpenes(taraxerol,tarax-asterol), inulin (about 25% in the autumn), sugars, glycosides, phenolic and citric acid, asparagine, vitamins A, C, B, potassium. Leaves: Carotenoids, vitamins A, B, C, D, minerals (potassium and iron). RELATED SPECIES: The true dandelion is often confused with a few different branched and bristly plants known collectively as “false dandelion” [Agoseris species). In China, T. monogolicum is used to treat infections, especially mastitis.

HISTORY: Dandelion was probably introduced into European medicine by the Arabs, who were writing about its virtues in the 10th century. Medieval pharmacists named it Taraxacum from the Greek taraxis, “to move or disturb”, but the name originally may have come from the Persian name for the herb, tarashqun. Both the Persians and East Indians used it for liver complaints. Dandelion became an official European apothecary drug in the 16th century, and one of the products sold was fresh dandelion juice. The shape of the leaves gives dandelion the French name, dents de lion, or “teeth of the lion.” Another French name, pis en lit, or “pee in bed,” celebrates its diuretic effects.

T A R A X A CUM OFFICINALE

Star-disked Dandelion, just as we see them, Lying in the grass, like sparks that have leapt From kindling suns of fire.

—■'Dandelion" The Professor at the Breakfast Table. Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), American

CULINARY: The young leaves, which are richer in vitamin A than carrots, can be mixed in salads or steamed and topped with a dressing. While in Greece, 1 dined every night on horta—a side dish of dandelions or other bitter greens drenched in olive oil. The English, who are not inclined toward bitter foods, do indulge in young dandelion greens on sandwiches with butter and salt, sometimes sprinkling them with pepper or lemon juice. Older leaves can be eaten if the'bitter center rib is removed. The Pennsylvania Dutch pour a dressing of hot cider vinegar and sugar over their dandelion salads—traditional fare for Maundy Thursday. The roasted root makes a coffeelike tea or is added to coffee as an extender. The taste of flower buds fried in butter somewhat resembles mushrooms, and the buds are added to eggs. The Arabians make a yublo cake of honey, olive oil, flour, rose petals, and dandelion buds. Dandelion flower wine and beer were originally tonics with less alcoholic and certainly more medicinal properties than commercial beer today. The English enjoyed dandelion, nettle, and yellow dock beer. Recipes are found in the booklet On the Trail of the Yellow Flowered Earth Nall: A Dandelion Sampler by Peter Gail (Goosefoot Acres Press, PO. Box 18016, Cleveland Heights, OH 44118—it also sells canned dandelion greens and Amish Dandelion Flower Jelly). MEDICINAL: Dandelion root is a “blood purifier” that helps both the kidneys and the liver to improve elimination. It helps clear up many eczema-like skin problems that result when the kidneys or liver don’t remove impurities from the blood. Used over a period of time, the root has successfully treated liver diseases, such as jaundice and cirrhosis, as well as dyspepsia, gallbladder problems, and gallstones.' It also improves appetite and digestion and is a mild laxative that works well to resolve chronic constipation. Clinical studies have favorably compared it to the often-prescribed diuretic drug Furosemide''” Instead of pulling potassium out of the body like most diuretics, dandelion helps the body to replace it.^ Most herbalists consider the root the diuretic of choice for treating rheumatism, gout, and heart disease. It is also suggested for women’s hormonal imbalances, especially those relating to liver or kidney problems, and Lydia Pinkham (1819-1883) included it in her famous women’s tonic. The leaves have some weak antibiotic action against Candida.

CONSIDERATIONS: The fresh latex that appears as white, sticky liquid in the root, and especially in the stem, can be caustic and cause skin irritations. One advantage of this property, however, is that it removes warts if applied religiously a few times daily. Use the dried root to prepare tea.

OTHER: It is an important honey plant, but the bees aren’t alone —about 93 species of insects visit dandelion for its nectar. During Word War II, a rubber latex was made from the Russian dandelion (T. kok-saghyz).

Dear common flower that grow st beside the way.

Fringing the dusty road with harmless gold First pledge of blithesome May

Which children pluck, and, full of pride, uphold High-hearted buccaneers, o erjoyed that they An Eldorado in the grass have found.

Which not the rich earth's ample round May match In wealth, thou art more dear to me Than all the prouder summer-blooms may be.

—“To The Dandelion " James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), American

Taraxacum officinale Dandelion

T E U C R I U M CHAM A EDRYS

Dandelion Wine

4 quarts (4.51) water

3 quarts (3.51) dandelion blossoms, fully open and dry 3 pounds (1.35 kg) sugar

1 orange, sliced

2 lemons, sliced 1 yeast cake

Pour boiling water over the freshly picked blossoms. Let stand 3 hours. Strain the liquid into a large cooking pot and add sugar to the liquid. Cook over medium heat 15 minutes. Place orange and lemons in a 2-gallon (7.6-1) container. Pour the hot liquid over the fruit. When cooled to 100° F(37° C), remove 1 cup (240 ml) and dissolve the yeast in it, then add to the rest. Let sit 12 hours and strain. Return mixture to the container, cover with layers of cheesecloth and let stand at room temperature 2 months. Filter, bottle, cap, and store in a cool place. In 6 months, strain into bottles and sample.

Greek Horta

The traditional but less nutritious Greek method is to boil the greens. For other variations, serve this dish raw or combine the greens with other vegetables.

15 dandelion leaves

1 small onion, sliced 8 black olives

2 tablespoons (30 ml) olive oil

1 tablespoon (15 ml) cider vinegar or lemon juice Salt to taste

Steam dandelion leaves and onion until soft. Serve mixed with olives and topped with the oil and vinegar. Season with salt.

Teucrium chamaedtys • Germander

FAMILY: Lablatae.

DESCRIPTION : Low-growing, full shrub. Height; 1 foot (30 cm). Width: 1 foot (30 cm). Flowers: Purple, rose to whitish, small, growing among leaves on upright stems. Leaves; Stiff, small, gray-green, marked with purple. Oblong, somewhat oak-shaped, but toothed and slightly hairy, to V 2 inch (1.25 cm) long, aromatic. Blooms: June to September.

HABITAT: A Mediterranean native that also grows in Europe and Syria, often around ruins where it was once cultivated. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 5 to 6. Germination: 3 to 5 weeks. Space: 12 to 15 inches (30 to 37.5 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° F(21° C). Soil: Well drained, average, light, dry. pH: 7-8.5. Sun; Full sun. Propagation: Plant seeds, divide clumps, or take cuttings. May experience some winterkill in zones 5 to 6, but comes back if mulched during the winter.

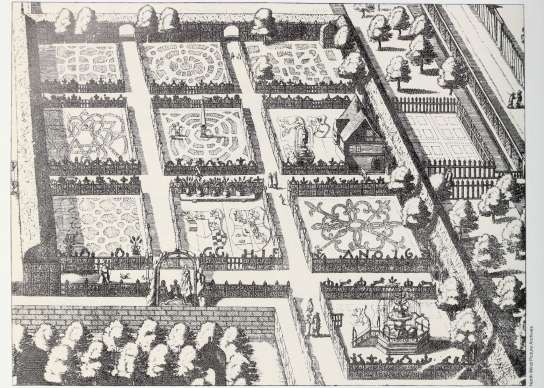

GARDEN DESIGN: Germander is a popular edging plant because It has a compact growing style that is dense enough to be trimmed into a hedge and it puts on rapid growth after pruning, which quickly fills any gaps. It formed border designs in formal Elizabethan knot and maze gardens, often interwoven with thyme. The soft coloring of the leaves and flowers adds a nice contrast to herbs with deeper pink and purple flowers.

CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil includes caryophyllene (60%), glycosides, tannins.

RELATED SPECIES: Cat thyme ("T marum) has a sharp smell that cats enjoy. It is 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 cm) high, with soft fuzzy leaves. It won’t tolerate winter temperatures below 20° F (-6.6° C). Dwarf germander [T. chamaedrys ‘Prostratum’) is a low-growing variety that forms a thick carpet. Wood sage, or garlic germander (T. scorodonia), with its green-yellow flowers and camphorlike fragrance, was used to bring on menstruation and as a treatment for skin- and blood-related diseases. The silver tree germander (T. fruiticans) Is a large, 4-foot (1.2-m) silver-green plant. Australian native germanders (T racernosum and T. corymbosum) are garden plants that are not used medicinally. T. polium treats digestive problems. Including ulcers. In Arab countries.

HISTORY: Germander is botanically named after Teucer (half-brother of Ajax), who gave it to his father-in-law. King Dardands of Troy, probably for gout. The herb had Its moment of historical glory when the 16th-century German Emperor Charles V was cured of gout after drinking germander tea for 60 days. It helped the Duke of Portland with the same malady In the 18th century and became the key Ingredient in Europe’s celebrated “Portland Powders.” They were manufactured well Into the 19th century. The 17th-century herbalist Culpeper suggested drinking germander tea as an antidote to poisons and applying it on snakebites. He also steeped the flowering tops in wine to kill intestinal worms.

CULINARY: Used In tonic wines and as a bitter flavoring in liqueurs and mixed drinks.

MEDICINAL: In addition to curing gout, germander is used to treat indigestion and to stimulate appetite and bile production. It was previously recommended to treat uterine obstructions and water retention and for reducing fevers. It was once considered horehound’s equal in relieving colds, flus, and coughs, although it is seldom used for those maladies today.

THALICTRUM AOUILEGIFOLIUM

t

THYMUS VULGARIS

Thalictmm aquilegifolium • Meadow Rue

FAMILY: Ranunculaceae.

DESCRIPTION : Tall, graceful herb. Height: 3 to 6 feet (.9 to 1.8 m). Width: 2 feet (60 cm). Flowers: No petals, but with long pink or purple stamens that are very prominent, striking, in open clusters. Leaves: Blue-green, smooth, divided into 3 segments, often with rounded lobes, resembling columbine {Aquitegia species). Blooms: May to June.

HABITAT: Europe, Asia. ^

CULTIVA TION: Perennial. Zone: 5. Germination: 15 to 30 days. Space: 1 to 2 feet (30 to 60 cm). Soil Temperature: 50° to 60° F (10 to 15° C). Soil: Well drained, loamy, moist. pH: 5.5 to 7.5. Sun: Partial shade or full sun with plenty of water; complete shade in warmer regions. Propagation: By seed or root division.

GARDEN DESIGN: Very ornamental. Flowers have an airy quality. Choose a somewhat protected place because high winds can bend it over.

CONSTITUENTS: Alkaloid.

RELATED SPECIES: The popular flower garden cultivars and Asian species are available with different colored stamens. Southern Europe’s T. angustifolium was used in folk medicine to reduce fevers. In 1977, T. dasycarpum showed tumor-inhibiting properties, attributed to the alkaloid thalicarpine.

HISTORY: Dioscorides used the leaves of thalictrum (from tha-lic, “to bloom”) to cure old wounds. Gerard, calling it “bastard rhubarb” (probably T. minus), noted that the leaves and especially the roots were laxative. Native Americans considered purple meadow rue (T. dasycarpum) a love potion that could reconcile quarreling lovers. The seeds were sometimes placed in a couple’s food by relatives trying to restore peace in the home. Smoking the dried seeds was also said to bring luck in both hunting and courting. They used the stems for straws, and a few different tribes named it “hollow stem.” The leaves and seeds were placed on muscle cramps, and the seeds were sprinkled on herbal poultices to increase their potency. Roots were sometimes used on snakebites or made into a tea to reduce a fever.

MEDICINAL: Meadow rue is a purgative and diuretic. The 1916 U.S. Dispensatory described it as “bitter and tonic, for vaginal infection.” It is a bitter digestive tonic that contains berberine (also found in goldenseal) or a similar alkaloid. The leaves were sometimes added to spruce beer in the 19th century as a digestive tonic. CONSIDERATIONS: Handling the plant causes itching or dermatitis in many people.

OTHER: The leaves produce a yellow wool dye. The cut flowers of meadow rue are quite lasting, and the cut foliage resembles a large version of maidenhair fern. It can also be dried for wreath making.

Thymus vulgaris • Thyme

FAMILY: Labiatae.

DESCRIPTION : Creeping groundcover. Height: 1 foot (30 cm). Width: 1 foot (30 cm). Flowers: Small, white to lilac, V-4 inch (1.88 cm) long, densely cover plant. Leaves: Small, almost oval, coming to a point, very fragrant, Vie to Vs inch (5 mm to 16 mm) long. Blooms: May to August.

HABITAT: The west Mediterranean to southwest Italy, on dry, rocky soil. Cultivated commercially in Europe, especially Hungary and Germany.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 4. Germination: 3 to4 weeks. Space: 1 foot (30 c '■). Soil Temperature: 55° F (13° C). Soil: Well drained, light, rather dry. pH: 6 to 8. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: By seed, cuttings, root division, or layering. The fine root system makes thyme more difficult than most herbs to move. Transplant it so it has plenty of time to establish its fine root system months before a hard freeze. Even established plants can be damaged if the soil freezes solid and heaves. A layer of sand on top of the soil helps prevent damage from freezes. Eventually the clumps die out in the center, but if this occurs after only 2 to 3 years, it can indicate poor growing conditions. Studies at the University of Granada, Spain, found that maximum essential oil potency occurs in the summer months of July and August.

GARDEN DESIGN: Thyme is suitable in rock gardens and borders, alongside pathways, and as a fragrant groundcover. It is used in Elizabethan-style, formal knot gardens because its dense growth allows trimming. Thyme looks particularly nice cascading over the side of a hanging pot or raised terrace. Different varieties planted together highlight each other’s colors.

THYMUS VULGARIS

i

CONSTITUENTS: Essential oil (to 2.5%) includes phenol, thymol (to 40%), carvacrol; terpenes; flavonoids; saponins. RELATED SPECIES: There are 200 to 400 species of thyme, including numerous cultivars. It is no surprise that there is confusion in proper identification, even in nurseries. All are suitable culinary herbs. “Flavors” include lemon thyme [T. x cltriudorus [pers.]). caraway thyme (T. herba-barona), creeping thyme (T. praecoxssp. arcticus), a tight, 4-inch- (10-cm-) tall groundcover with rosy, purple flowers.

HISTORY: Sumerian cuneiform tablets in 2750 B.C. suggested that thyme be dried and pulverized with pears and figs and enough water to make a thick paste for a poultice. The Egyptians used tharn, “thyme,” for medicine and to embalm their dead. The Romans liberally strewed thymum on their floors, burned it to deter venomous creatures, and flavored their cheese with it. Ancient Greeks felt complimented when told they “smelled of thymbra.”Then name for the herb (probably T. capitatus) might be associated with thymain, “to burn as incense,” and Ihyniete their word for altar, although most sources claim it came from thumus, meaning “energy.” For centuries, the bees on Mount Hymettus near Athens have produced a famous wild thyme honey. St. Flildegard mentioned it as a treatment for leprosy, paralysis, and “excessive” body lice.

CULINARY: Benedictine monks added it to their famous elixir. Today it is found in chowders, sauces, ton.atoes, gumbos, pickled beets, stews, stuffings, and many different vegetables. By the way, when cookbooks refer to a “sprig” of thyme, they usually mean a half teaspoon (2.5 ml).

MEDICINAL: Thyme’s main medicinal role is in treating coughs (including whooping cough) and clearing congestion. It makes an excellent gargle or mouthwash for sore throats and infected gums. Many pharmaceutical gargles, cough drops, mouthwashes, and vapor rubs contain thyme’s constituent thymol, which destroys bacteria, some fungus,' and the shingles virus (herpes zoster). Participants in a study who rinse twice daily with Lis-terine™, containing thymol (with eucalyptol and menthol), found they developed 34% less gum inflammation and new plaque formation. Thyme improves digestion, relaxing smooth muscles. It reduces the prostaglandins responsible for many menstrual cramps.^ Thyme also helps destroy intestinal parasites (especially hookworms and roundworms).

AROMATHERAPY: Rudyard Kipling wrote of the “wind-bit thyme that smells like the perfume of the dawn in paradise.” The fragrance of thyme is said to dispel melancholy and nightmares, at least according to 17th-century herbalist Culpeper. Both red thyme oil and the redistilled white thyme are available to use in baths for rheumatism, in liniments, and in massage oils. The term Ihy-miatechny, from thyme and techne, or “art,” was once used to describe the “art of using perfumes as medicine,” or aromatherapy. OTHER: Thyme is found in many antimildew preparations and has long been used in linens to deter bugs. Studies show it kills mosquito larvae.'* Thyme is used occasionally in potpourris and soap making. In addition, it is reported to allow one to see fairies, who are said to dance in beds of wild thyme on Midsummer Eve (.lime 20-21).

Young fairies perched in Rosemary Branches,

while their elders danced in the Thyme.

—Leaves Vernon Quinn, 19th Century, American

Ninon de L’enclos’ Hair Rinse

This recipe dates from circa 1630.

2 tablespoons (30 ml) thyme, crushed 1 tablespoon (15 ml) mint, crushed 1 tablespoon (15 ml) rosemary, minced 1 pint (500 ml) white vinegar

Combine ingredients and let sit in a warm place for 3 weeks, then strain.

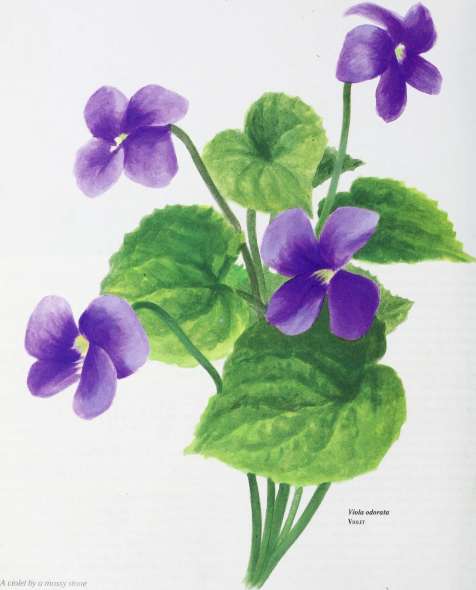

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows Where ox-lips, and the nodding violet grows;

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine.

With sweet musk-roses, and with eglantine.

—A MibsuMMER Nights Dream. William Shakespeare (1564-1616), English

Here of Sunday morning My love and I would lie, and I would turn and answer Among the springing thyme.

—“The Shkopshike Lad," A. E. Housman(1839-1936), English

Now the summer’s in prime Wi’ the flowers richly blooming,

And the wild mountain thyme A ’ the moorlands perfuming

“The Braes O’ Balquhither,” Robert Tannahill(1774-1810), Scottish

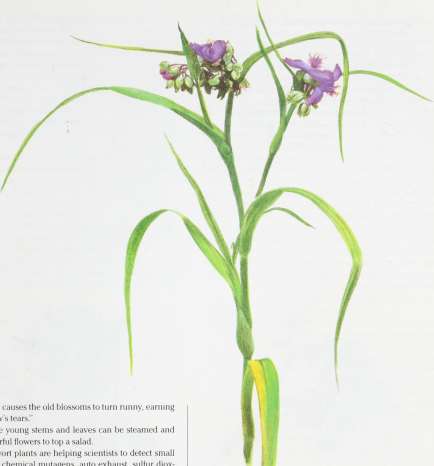

Tradescantia virginiana • Spiderwort

FAMILY: Commel inaceae.

DESCRIPTION : Spiderlike fronds. Height: 3 feet (90 cm). Width: 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Flowers: Violet-purple, occasionally rose or white, 3 petals with 3 sepals and 6 stamens, 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide. Only last 1 day. Leaves: Thin and pointed, 1 foot (30 cm) long, 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide. Blooms: May to August, with a long flowering period. HA BITA T: From Connecticut to Georgia, west to Missouri. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 4 to 5. Germination: 10 to 30 days. Space: 2 feet (60 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° F (21 ° C). Soil: Moist, well drained, fairly rich preferred, but poor conditions tolerated. pH: 5.5 to 7. Sun: Filtered shade or full sun. Propagation: By seed, cuttings, dividing root clumps, or cutting off side shoots from stolons (aboveground runners).

GARDEN DESIGN: Spiderwort is an attractive plant that is used in landscaping design. It is best shown off when placed individually or in a pot that emphasizes its graceful form. Since it can eventually overrun an area with good growing conditions, consider interplanting with butterfly weed or other aggressive herbs or containing the bed.

RELATED SPECIES: Most horticultural spiderworts are T. x andersoniana. The most popular relative is the common house-plant wandering jew (T albiflora), a widespread weed in parts of Australia.

HIS TORY: Spiderwort may refer to the plant’s spiderlike appearance or its previous use to cure spider bites. Instead of falling off, an

TRADESCANTIA V I R G I N I A N A

enzymatic reaction causes the old blossoms to turn runny, earning it the name “widow’s tears.”

CULINARY: The young stems and leaves can be steamed and eaten; use the colorful flowers to top a salad.

OTHER: Spiderwort plants are helping scientists to detect small levels of radiation, chemical mutagens, auto exhaust, sulfur dioxides, and pesticides. The genetically dominant blue cells in the stamens turn pink 8 to 18 days after exposure to such substances and can be seen under an ordinary microscope. In 1977, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) placed spiderwort plants near high-risk areas to monitor air pollution. According to spiderwort tests, petroleum refineries and mixed chemical processing plants have the highest mutation rates. In 1980, the plants detected radiation at the Trojan Nuclear Power Plant in Prescott, Oregon, and at other reactors. Dr. Sadao Ichikawa of the Saitama University in Japan found that as little as 150 millirems of radiation produce mutations. (The U.S. federal maximum level for man-made radiation is 170 millirems a year.) These occurred mostly on the windward side, only when the reactor was on. National Aeronautic and Space Association (NASA) scientists found that spiderwort is also one of the most effective plants at absorbing formaldehyde caused by poor ventilation in buildings. But before you run out to the nursery, know that you will need 70 plants for every 2 V 2 yards (2.3 m) of floor space!

Tradescantia virginiana Spiderwort

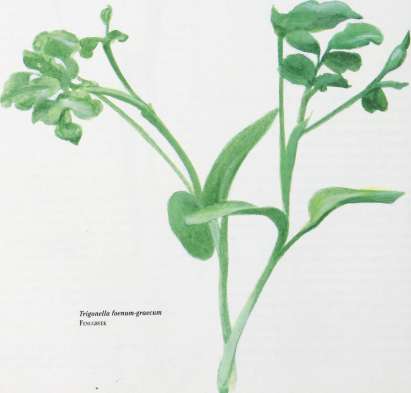

TRIGONELLA FOENUM-GRAECUM

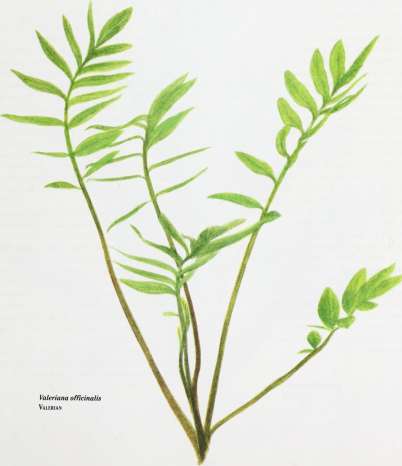

Trigonella foenum-gmecum • Fenugreek

FAMILY: Leguminosae.

DESCRIPTION: Shrubby. Height: 2 feet (60 cm). Width: 1V 2 feet (45 cm). Flowers: Whitish, by themselves or in pairs. Leaves: Divided into 3 almost cloverlike shapes, 1 inch (2.5 cm) long, toothed around the edges. Fruit: Beaked pod, IV 2 to 2 inches (3.75 to 5 cm) long, containing 10 to 20 seeds. Blooms: June.

HABITAT: Southern Europe and Asia in open clearings. Cultivated commercially in Lebanon, Egypt, and Argentina. CULTIVATION: Annual. Germination: 2 days. Space: 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 cm). Soil Temperature: 70° to 75° F (21 ° to 24° C). Soil: Dry and warm, or will rot. pH: 5.5 to 8.2. Sun: Full sun. Propagation: Start from seed in spring. (The seed sold at natural food stores for sprouting is suitable.)

GARDEN DESIGN: The profusion of sweetpealike flowers makes fenugreek a good garden addition. It is a legume that adds nitrogen to the soil and can be used as a cover crop to decorate and prepare new garden areas at the same time.

CONSTITUENTS: Mucilage (to 30%), alkaloids (trigonelline, gentianine, carpaine), steroidal saponins (mainly diosgenin), flavo-noids, fixed oil (8%), protein (25%), amino acids (lysine, tryptophan, leucine, histidine, arginine), lecithin, vitamins A, B,, C, minerals (calcium, iron).

HISTORY: Egyptian papyri tell of fenugreek’s use as a food and to reduce fevers, as well as an ingredient in kuphi smoke, used in fumigation and embalming. It was discovered in King Tut’s tomb (1323 B.C.). Ancient Arabic physicians used it, and a Middle Eastern greeting speaks of fenugreek, or helbah: ‘May you tread in peace on the soil where it gave new strength, and fearless mood, and gladiators, fierce and rude, helbah grows!” Fenugreek is an abbreviation of the early Latin name, foenum, “hay,” graecum, “from Greece.” It was an early fodder crop that has improved the scent of poor hay since at least the 2nd century B.c. Charlemagne ordered it grown in the 9th century and it was spread throughout Europe by Benedictine monks.

CULINARY: The seeds themselves seem to have little odor, but it increases with drying, becoming quite strong when cooked. A fenugreek extract is sold in grocery stores to give confections a maple or butterscotchlike taste. Greeks eat the seeds boiled or raw with honey; East Indians add them to curries and chutneys; and Egyptians roast them for a coffee substitute or eat the sprouts as vegetables. It is a main flavoring in the Middle East confection halvah and in breads from Arabia, Ethiopia, and Egypt. In all of these countries, including East India, the leaves are served as a vegetable. For the Ethiopians, fenugreek, or abish, is a most important food, along with beans, peas, and lentils. In North Africa, and particularly in Tunisia, the flour is used for putting on weight:

TRILLIUM E R E C T U M

3.5 ounces (100 g) of fenugreek is 25% protein, and contains 335 calories and 18 ounces (5.2 g) fat. While this may be discouraging to some people, harem women purposely ate the seeds to make them fleshier and more attractive, an indication of how fashions change! Fenugreek not only increases body weight, but also helps improve protein utilization, inhibits phosphorus secretion, and increases erythrocyte count.'

MEDICINAL: Fenugreek seeds are used in Indian and Ethiopian medicine to treat indigestion and diarrhea. Egyptians soak the seeds to make them into a thick paste that they claim is equal to quinine in preventing fevers. It is a folk remedy for diabetes, and clinical studies are proposed to support the preliminary findings that it reduces both blood sugar and cholesterol levels and delays sugar glucose transfer from the stomach to blood in animals.^ It has a stimulating and toning effect on the uterus, possibly due to its diosgenin, the same hormonelike substance found in wild yam that closely resembles the body’s own sex hormones. Fenugreek is currently being cultivated for more investigations.^ In China, it is given to men to correct impotence and to women to reduce menopausal sweating and depression and as a calcium source. Fenugreek is also used to increase male fertility, although one study shows that direct contact with it may be spermicidal.'’ The Latin Americans boil it in milk, then drink it to increase mother’s milk. A poultice has been used for rheumatic pain, burns, to draw out boils, and to relieve sore breasts.

CONSIDERATIONS: Because it stimulates the uterus, restrict use during pregnancy. The straight essential oil, similar to that of dill and parsley, can be narcotic.

OTHER: Fenugreek is still used as a flavoring in veterinary medicines, in conditioning powders for horses and cattle, and as a fodder plant. The pharmaceutical and food industries use it as an emulsifying agent. It is used as a yellow dye in India. The seeds are also planted as an agricultural cover crop.

“Maple” Pancake Syrup

cup (120 ml) fenugreek seeds 1 cup (240 ml) water V4 cup (60 ml) honey

Soak the seeds in the water for 2 hours. Bring the water to a boil and simmer about 5 minutes, until mush. Stir in honey.

Trillium erectum • Trillium

(Previously T. flavum)

FAMILY: Liliaceae.

DESCRIPTION: Height: 2 feet(60cm). Width: 10 inches(25cm). Flowers: Brown-purple, occasionally white, yellow, or green, to 2 inches (5 cm) long, almost erect on 4-inch (10-cm) stems, surrounded by leaves. Leaves: Broad, triangular. Rhizome: Dull brown, often ringed with lines, with wrinkled rootlets underneath, yellow to red-brown. Tastes sweet, then acrid. Blooms: May to June. HABITAT: Canada, through the Midwest and east coast of the United States. Found on moist soils in shaded woods.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 2 or 3 to 7. Requires a cold winter to go dormant. Germination: 1 month. Stratify fresh seed. Space: 1 foot (30 cm). Soil Temperature: 60° to 70° F (15° to 21° C). Soil: Moist, fertile, humus. pH: 4.5 to 6.5. Sun: Partial shade. Propagation: By seed or root division. The first year from seed produces only 1 leaf. It takes 3 to 4 years to produce flowers from seed. Very hardy once established, except in hot climates. Makes a suitable potted herb and can be forced for winter flowers indoors. GARDEN DESIGN: Very striking, especially when in bloom. Plant where larger herbs won’t overshadow it. It contrasts well with other spring wildflowers, such as bloodroot. Be forewarned; flies pollinate the rancid-smelling flowers, so you may not want a patch of trilliums under a window.

CONSTITUENTS: Steroidal saponins(diosgenin), essential oil. RELATED SPECIES: There are other species of trillium, including the most popular, white-flowering trillium (T. grandi-florum), with fragrant, large flowers.

HISTORY: Trillium’s name describes its 3 (tri) distinct petals, 3 sepals, and 3 leaves. When introduced in 1830 by Rafinesque, any species was used medicinally, although the Native Americans regarded the white-flowering trilliums most effective. Then, in 1892, Charles Millspaugh declared that only T. erectum should be used. Many species were actually grouped together and classified as T. pendulum (a name no longer used) by wildcrafters. Called wake-robin, it is said to wake the robins into song as it pushes through the last snowdrifts in early spring.

MEDICINA L: The trillium rhizome is used mostly for menstrual disorders, such as relieving cramps and excessive flow, and for vaginal infections. It was an ingredient in the Compound Elixir of Viburnum Opulus (cramp bark), which was used for similar women’s complaints. Trillium is also used after childbirth to stop bleeding, which gave it the common name birth root, or beth root. The diosgenin it contains (which also occurs in wild yam root [Diosco-rea uillosaj) is related to human sex hormones and to cortisone. As an external astringent, it can be applied to wounds, ulcers, and sores and used to treat chronic skin infections. Taken internally, it stops digestive tract bleeding and is included in diarrhea and dysentery treatments. It is also used to relieve lung congestion.

Trillium erectum. Trillium catches the eye with its significant three petals borne above three distinct leaves.

195

© Steven Foster

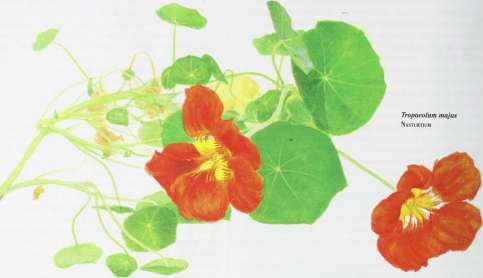

TROPAEOLUM M A J U S

t

Tropaeolum majus • Nasturtium

FAMILY: Tropaeol iceae.

DESCRIPTION : Climbing or trailing vine. Length: 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3 m). Flowers: Broad petals, 2V2 inches (6.25 cm) across, yellow, orange, or red and sometimes spotted, funnel-shaped, with long spur in back. Leaves: Almost round, slightly ruffled, 2 to 7 inches (5 to 17.5 cm) across, thin, slightly succulent. Fruit: Globelike seedpods filled with many seeds. Blooms: Throughout the summer, most of the year in warm climates.

HABITA T: Native to the Andes in South America. CULTIVATION: Annual. Germination: 7 to 10days. Fresh seed is best. Needs darkness to germinate. Space: 1 foot (30 cm). Soil Temperature: 65° F (18° C). Soil: Well drained, slightly sandy, average-will produce less flowers if too moist or rich. pH: 7.5 to 8.5. Sun: Full sun in cool climate or partial shade in hot climate. Propagation: From seed. Flowers 8 weeks after germination. Best in cool conditions and will bloom in the winter in warm climates. GARDEN DESIGN: The brightly colored flowers are a popular ornamental in flower gardens. They can climb up a wall or fence, hang from a pot, or become a rapid groundcover. Place them so they won’t detract from small herbal flowers. Watch out! It may attract aphids during hot weather.

CONSTITUENTS: Glycoside (glucotrapaeoline), which hydrolyzes to antibiotic and antifungal sulfur compounds and an essential oil, isothiocyanate (or mustard oil); high vitamin C content in flowers and leaves.

RELATED SPECIES: The dwarf (T. minus) scrambles more than climbs. T. tuberosum is an important vegetable in its native Andes.

HISTORY: Introduced to Spain by conquistadores in the early 17th century, nasturtium was called Indian cress and promoted as a vegetable and medicine. It was originally placed in the same family as watercress. Calling it yellow lark’s heel because of the flower’s spur, in 1629 John Parkinson suggested that the fragrant nasturtium could be combined with carnations and clove pinks “to make a delicate tussie-mussie,... or nosegay, both for sight and sent.” CU LIN ARY: The flowers and especially the buds are pickled as a caper substitute. The fresh leaves and flowers are eaten in salads and sandwiches, much like lettuce, but in smaller amounts. Any part of the plant can be whipped with warmed butter into a tasty “nasturtium butter” to spread on crackers or bread. MEDICINAL: Nasturtium flowers and leaves contain a natural antibiotic that doesn’t interfere with intestinal flora—it is even effective against some microorganisms that have built up resistance to common antibiotics. The leaves are eaten or made into tea for both the reproductive and genitourinary tract and respiratory infections. It is reputed to promote red blood cell production. The juice of the fresh plant has been rubbed on itching skin.

CONSIDER AT IONS: Large amounts of the seeds are purgative. OTHER: Has been fed to chickens to prevent and cure fowl pox.

TUSSILAGO F A R F A R A

Nasturtium Capers

This recipe was adapted from The British Housewife, written in 1770 by Martha Bradley. Of the initial cooking process of the buds, she wrote, “They will fade a little, and they will soon be as dry as when just gathered; and being thus faded they will take the vinegar better than if they had been quite fresh.” If you are patient and let them sit 6 weeks, “In that Time the Vinegar will have penetrated them thoroughly and the Taste of the Spices will be got into their very Substance, so that they will be one of the finest Pickles in the World,” promised Bradley. ‘

Nasturtium buds to fill a 1-quart (I-l) jar 1 quart (11) vinegar ’/4 teaspoon (1.25 ml) nutmeg V 2 teaspoon (2.5 ml) black pepper, whole 6 cloves

Stir buds in cold water, drain, and repeat, then lay on a sieve to dry. Loosely fill a well-washed quart (litre) jar with buds, sprinkling in spices as you go. Fill the jar with vinegar and put on a lid. Let sit 6 weeks before opening.

Latin Chicheghi Salatassi (Nasturtium Salad)

Here is a recipe from the Turkish Cookery Book of 1862 by Turab Effendi.

Put a plate of flowers of the nasturtium in a salad-bowl, with a tablespoon of chopped chervil; sprinkle over with your fingers half a teaspoonful of salt, two or three tablespoons of olive oil, and the juice of a lemon; turn the salad in the bowl with a spoon and fork until well mixed, and serve.

The Indian cress our climate now do’s bear,

Calld Larksheel ’cause he wears a horse-man’s spur.

This gilt-spun knight prepares his course to run Taking his signal from the rising sun,

And stimulates his flow 'r to meet the day So Castor mounted spurs his steed away This warrior sure has in some battle been For spots of blood upon his breast are seen.

—Abraham Cowley (1618-1667), English

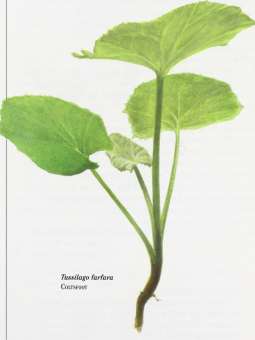

Tussilago farfara • Coltsfoot

FAMILY: Compositae.

DESCRIPTION: Low-growing and spreading. Height 4 to 8 inches (10 to 20 cm). Width: 6 inches (15 cm). Flowers: Bright yellow, 1 inch (2.5 cm), resemble dandelions, but held aloft on purplish, scaly, 8-inch (20-cm) stems. Turn into white tufted seed heads. Leaves: Slightly lobed and toothed around the edge. Dull green, flat with a downy white underside, 4 to 7 inches (10 to 17.5 cm) wide. They appear in late spring, long after the flowers. Mucilaginous and somewhat bitter-tasting. Blooms: March to April. HABITA T: Native to Europe, northern and western Asia, northern Africa; naturalized in other areas, including the northeastern United States, in moist, loamy soils of wastelands.

CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 2. Germination: 1 to2 weeks. Space: 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm). Soil Temperature: 60° to 70° F (15° to 21° C). Soil: Heavy, rich loam that holds moisture. Will grow in poor conditions, but develops more bitterness. pH: 4.5 to 7.5. Sun: Sun or partial shade. Propagation: Grow from seed or divisions. Once established, it will happily take over the garden if not restrained; 3 to 6 cuttings a year are possible.

CONSTITUENTS: Flavonoids(rutin, hyperoside, isoquercetin), polysaccharide mucilage (8%), pyrrolizidine alkaloids, sterols, essential oil, minerals (potassium, calcium salts), tannin, inulin. RELATED SPECIES: Coltsfoot is often confused with western coltsfoot (Petasites spp.), a much larger herb used for lung congestion that grows wild in the northwest United States. They have similar medicinal uses.

HISTORY: The ancients imagined that the outline of coltsfoot leaves resembles a colt’s footprint. The Romans called it Filius ante patrem, “the son before the father,” because the flowers appear and wither in the spring before the leaves emerge. For the same reason, the Russians call it mat i matcheha, or “mother and stepmother.” In Pliny’s day (the 1st century A.D.), Romans inhaled smoke from coltsfoot leaves burnt on cypress charcoal through a reed, then sipped wine, to stop obstinate coughing. For centuries, it was a popular ingredient in herbal tobaccos and is still the main ingredient in “British Herb Tobacco” (with buckbean, eyebright, betony, rosemary, thyme, lavender, and chamomile). In the past, a picture of the coltsfoot flower painted on the doorpost identified French pharmacies.

<S> Kathi Kevilie

Urtica dioica • Nettle

U R T I C A DIOICA

*

Tussilago farfara. The unusual characteristic of coltsfoot flowers is that they appear before the leaves, signaling the early days of spring.

CULINARY: The leaves were eaten as a vegetable and the flowers were once used to flavor wine.

MEDICINAL: Herbalists, from Dioscorides in the 1st century to present-day practitioners, have recommended coltsfoot leaves for lung problems such as laryngitis, bronchitis, and asthma, and to control spastic coughing. It is a soothing expectorant, and the flavo-noids it contains reduce inflammation, especially in the bronchials. Even its name Tussilago comes from tussis, Latin for “cough.” Coltsfoot is also applied as a poultice to sores and ulcerations and as a cream for cold sores.

CONSIDER AT IONS: Coltsfoot contains traces of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA) (similar but not identical to those in comfrey root), and the jury is still out concerning its safety. The alkaloids cause liver toxicity in rats fed high daily doses, although not those given low doses.' More encouraging studies show that the immune systems of mice were stimulated when the animals were given an extract made from the whole plant.^ So far, the alkaloids have not been shown to cause any damage to human chromosomes in the test tube.^ A 1987 case reported an infant born with severe liver injury after her mother had consumed coltsfoot tea daily for a lung problem, but the tea was later proven to be adulterated with Petasi-tes, which contains much higher concentrations of PA. The early evidence in this case prompted Germany to ban 2,500 products containing herbs with PA in January 1089. They propose restricting coltsfoot to about 1 teaspoon of dried herb, 6 grams, or 1 microgram of PA daily for no more than 4 weeks.

OTHER: The feathery seed heads were once collected for pillow stuffing.

Coltsfoot’s a classical fixture In one old smoking mixture.

Some say after heating The leave’s fit for eating,

But that s a debatable issue.

— “Coltsfoot. ’’ James A. Duke (b. 1929), American

FAMILY: Urticaceae.

DESCRIPTION : Bristly herb with few branches. Height: 3 to 6 feet (.9 to 1.83 m). Width: 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). Flowers: Small, white, loosely clustered. Leaves: Oval, coming to a point, deeply serrated around edge, downy, covered with stinging hairs, to 6 inches (15 cm). Even slight pressure releases fluid from a capsule at the base of each hollow stinger hair. Blooms: June to September.

HABITAT: Eurasia, naturalized elsewhere, including Australia. CULTIVATION: Perennial. Zone: 2. Germination: 10 to 14 days. Space: 1 to 2 feet (30 to 60 cm). Soil Temperature: 65° to 75° F (18° to 24° C). Soil: Damp, rich with nitrogen. pH: 6.5 to 7.5. Sun: Full sun or partial shade. Propagation: By seed, cuttings, or root division. Likes to grow by running water.

GARDEN DESIGN: It might be wise to place nettle beyond reach of visitors in the garden, who may injure themselves touching and smelling the herbs.

CONSTITUENTS: Formic acid, which causes the painful reaction, found in hairs; indoles (histamine, serotonin); acetylcholine; minerals (iron, silica, potassium, manganese, sulphur); vitamins A, C; especially high in chlorophyll.

HISTORY: Nettles have supplied fiber for cloth and paper from the Bronze Age (4,000-3,000 B.c.) into the 20th century. The name is derived from the Anglo-Saxon netel, which some authorities think originated from noedl (a needle) because of its stingers. More likely, it comes from net, akin to the Latin fishnet, nassa, which was made out of nettles. Roman soldiers in Britain planted urtica, from urere, meaning “to sting,” to rub on their limbs so they could better tolerate the cold winter (probably U. pilulifera). Later, it was cultivated in Scotland, Denmark, and Norway to make fine linen, coarse sailcloth, and strong fishnets. Eventually, flax was preferred, but nettles were still used to weave coarse household cloths, called scotchcloth, from the 16th through the 19th centuries. Scottish poet Thomas Campbell (1777 to 1844) related.

In Scotland, / have eaten nettles, / have slept In nettle sheets, and / have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb,... I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other species of linen.

To make cloth, the nettles were cut, dried, and steeped in water, then the fibers were separated and spun into yarn. In the Hans Christian Anderson (1805-1875) fairy tale The Princess and the Eleven Swans, the coats the princess made for her brothers were woven from nettle. In Les Mis'erables, the character Monsieur Madeleine describes its virtues: