CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Yoenis led the professor, Uchenna, and Elliot through the narrow streets of Old Havana. They’d left Jersey to play in the garden, and Rosa sitting on an old wooden chair, watching him and throwing her head back with laughter.

As they left the house, Yoenis told them, “I have to stop in and see some friends around town. I’ll let you look for your unicorn and meet you back at my mom’s. You’re sure you’ll be able to find your way back?”

Elliot waved a hand at him. “Please. I once got lost in a shopping mall. It was awful. The worst three minutes of my life. I’ve never been lost since. I’ll just memorize the route we take.”

Yoenis looked at Uchenna. “Is he a little weird?”

“More than a little,” Uchenna replied. “But he’s the best adventuring buddy a kid could have.”

Yoenis rubbed Elliot’s curly hair. “I believe it.”

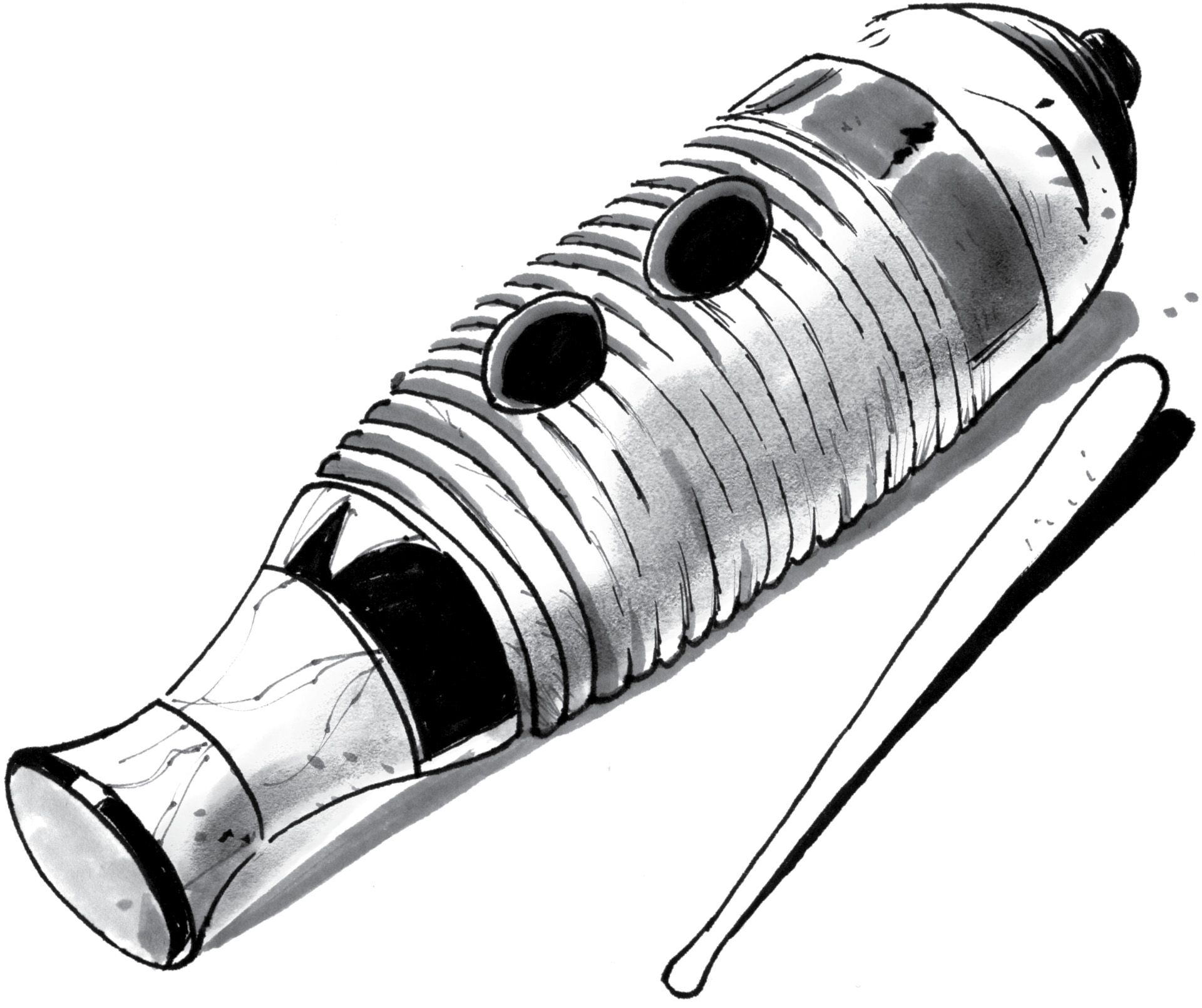

They turned from one shady, potholed street into another, and then they emerged into an open plaza. But this one did not contain a sparkling, modern hotel. Instead, shading the plaza was the bell tower of an old monastery. The monastery was topped with red terra-cotta tile, and the walls were made of a warm, sand-colored stone. In the center of the plaza, a fountain encircled by four stone lions gurgled merrily. A band played a syncopated rhythm with guitars, bongos, and an instrument that looked something like a wooden gourd.

“What’s that?” Uchenna pointed to the instrument as the musician ran a stick over the ridges on its front. She couldn’t help tapping her feet as they played—the instrument looked like fun.

“That’s a güiro,” Yoenis said. “It’s a Taíno instrument. And yet the rhythms that are making your feet tap uncontrollably are African rhythms. And the guitars are Spanish. This, mi gente, is what my mother was talking about. The combining of all of these traditions.”

Uchenna spun in a circle, moving her shoulders from side to side. And then she burst into song, giving lyrics to the infectious melody:

“We crashed in the water of Havana Bay

And the Madre de aguas charged us.

Until little Jersey scared her away

And Yoenis’s cousin barged us.”

Yoenis threw his head back and laughed. They danced their way across the plaza. Finally, Yoenis led them into one of the side streets, and the rhythm of the band faded behind them.

Uchenna sighed happily. “I think I am in love with Cuba. Why did you ever leave, Yoenis? You seem so much happier here.”

Yoenis’s smile faded, and immediately Uchenna regretted the question. “I—” she stammered, “I—I’m sorry. That was a nosy question. I shouldn’t have asked.”

Yoenis sighed. “It’s okay, Uchenna. It’s a perfectly reasonable question. I’ll tell you. The early 1990s were a really hard time for Cuba. We’d gotten a lot of support from the Soviet Union. But when the Soviet Union fell apart, all of the food and aid they sent ended. It was a horrible time. People were starving. So they started making rafts. Rafts out of trash, rafts out of tires, rafts out of driftwood. Whatever they could find. And they’d try to ride the raft the ninety miles across the ocean to Florida.”

“Whoa,” said Uchenna. “That is incredibly brave.”

“And incredibly dangerous!” Elliot added.

“You have no idea,” Yoenis agreed. “My dad wanted to go with the rafters and take me with him. He kept pointing out that he and my mother couldn’t even feed me three meals a day. How hungry we were. My mother, she wanted to stay. She had a job working for the Cuban government, recording Cuba’s cultural history. They had many fights. It was horrible.”

Yoenis’s face had become as dark as the clouds overhead. But like the clouds, no droplets fell.

“Finally, my dad convinced my mom that he and I should go. I don’t know how. But I do remember my last day at our house. I spent it with the Madre de aguas.”

“Really?” Professor Fauna asked.

“Yes. I was ten years old. I remember walking slowly around the garden, saying a silent good-bye to each plant, to the tiles, to the pavement stones. I tried to catch one last glimpse of the tiny hummingbird, the zunzún, that sometimes stopped by to visit. I was slowly sipping a can of cola that Mami had given me, trying to savor every last drop. It was a special treat for a very sad day.

“Then my dad called me from inside. ‘Ya es hora.’

“I turned back to the fountain. I wanted one last glimpse of the Madre de aguas, before I left. I wasn’t sure if I’d ever see her again. Please come, I remember thinking. Just one good-bye.

“I leaned over the fountain. The shadows stirred. Something dark and shimmery stirred.

“And there she was.

“She swam up from the shadows at the bottom, her tiny horns just pricking the surface of the water.

“I laughed, and she began to puff up and grow, like a balloon inflating. As she did, the water levels in the fountain went down. Then, she shrank again, and the water rose once more.”

Yoenis pursed his lips. In the momentary pause, Elliot said, “So, do you think she sucks up the water in order to grow? Like, through her scales or gills or something?”

Yoenis nodded. “Maybe,” he said.

Uchenna nudged Elliot. “Let him tell the story.”

“Right!” said Elliot. “Sorry. Science distracts me sometimes.”

Yoenis smiled. “No worries. Once she was little again, I asked the Madre de aguas to take care of my mom. Through the food shortages and the power outages. To look after her. And just as I finished asking this of the Madre de aguas, my dad called me again. Loudly. I jumped. And I spilled my can of cola into the fountain. The dark cola bubbled and spread through the water.

“Suddenly the Madre de aguas was growing large again, larger than before. Her scales gleamed. She raised her body out of the water, rising like a corkscrew. Soon, she was towering over me, and there was no water in the fountain at all.

“I’d never seen her get so angry, and I hadn’t seen her angry since, until today. So I apologized about a hundred times in one minute, and sopped up the cola from the lip of the fountain with my shirt. She calmed down, and shrank again, and the water rose. And the cola was gone—the water was totally clean.”

“I’m sorry,” Elliot said, “but I have to interrupt now. That may be how she provides fresh water to the islands—she purifies it by taking it in and letting it out again!”

“Maybe,” Yoenis agreed. “Though that would mean the impurities remain inside of her.”

“Which might put her in a really bad mood when there are a lot of impurities!” Elliot exclaimed.

“This is an excellent theory!” Professor Fauna agreed. “We shall have to write something up for the next issue of the Journal of the Proceedings of the Unicorn Rescue Society, Elliot!”

But Uchenna turned back to Yoenis. “So, you took a raft to Miami? Was it hard? Scary?”

“It was the worst,” Yoenis said. “We made it, but barely. And that journey tore my family apart forever. My dad passed away a few years ago. He never made it back to Cuba.”

Uchenna reached out her hand. Yoenis took it. They walked together, in silence, through the streets of Havana.