Chapter One

THE BOY

“Cork boots! I want cork boots!” cried Little Joe.

Dad sat on the wood-box, greasing his boots. Calk boots, called “cork boots” were twelve inches high and had sharp spikes all over their soles. Little Joe wanted to wear them and go stumping through the house like Dad.

“Makin’ splinters on the floor!” scolded Mom.

Everybody laughed at Little Joe and teased him.

“Your feet are too little, they’d fall off!” said Dad.

“You’re plumb cuckoo!” jeered Jinx.

“A fine logger you’ll be, ’fraidy cat!” teased big sister Sandy.

But Little Joe kept on coaxing.

“Cork boots! The very idea!” said Mom, her lips pressed tight. “You’ll never get a pair—I’ll see to that. I’m not raisin’ my son to be a logger, that’s for sure.”

Dad just laughed.

“Loggin’s in his blood, Nellie, don’t forget that. You’re not gonna make him a sissy-pants, if I have my way about it.”

Little Joe did not get the boots, but he kept on wanting them.

Little Joe’s father was a logger. He was called Big Joe Bartlett because he was so big and strong and husky.

Little Joe, whose real name was Joel, lived with Mom and Dad and his two sisters in a log house built by Granddad. It stood on a rise of ground above a small creek in southwestern Oregon. A bumpy dirt road ran along by the creek out to the highway. All around were mountains covered with a dense forest of trees.

Little Joe loved to climb trees. He climbed his first tree when he was only two. He ran out of the house and climbed a tree to get away from Mom. She came after him with a switch, but he only climbed higher.

“You little monkey!” she scolded. “Come right down here.”

But he did not come.

She threw away her switch and still he did not come. Then she saw that he was scared. And he did not know how to get down. She had to lift him down.

When he was five, Dad gave him an axe. So he began to chop trees down. He took a small saw of Dad’s and bucked (sawed) the trees into logs. He rolled the logs down the hill and watched. He laughed when they splashed into the creek.

“He’s a little logger, for sure!” bragged Dad.

Billy Weber was Little Joe’s best friend. Little Joe looked up to Billy because Billy was two years older than he. Billy had long shaggy hair and freckles on his nose. He was always barefoot in summer and his clothes were ragged. He lived over on the other side of the ridge, but he took a shortcut to Little Joe’s house. He came any time and was never in a hurry to go home.

Billy liked chopping trees down just as Little Joe did. His father was a logger, too, and he knew little else.

One day Billy and Little Joe went off up the hill, carrying their axes. They walked a while looking at trees on the way. Then they chose one and stopped.

“I’ll make a bet with you,” said Billy. “You chop it down …”

Little Joe listened.

“I bet you can’t chop it down by the time I climb up to the top and back down again,” said Billy.

“O.K.,” said Little Joe. “Go ahead. I’m a fast chopper. You’d better watch out.”

Billy started climbing and Little Joe began chopping the tree. He chopped faster and faster and the chips went flying. Soon the tree began to lean. It cracked loudly. Little Joe jumped out of the way just in time. It fell with a loud galump and a noisy rustle of the branches.

Little Joe won the bet. But where was Billy? He had climbed to the top, but hadn’t got back down again. Little Joe dropped his axe and stared.

“Where are you, Billy?” he called in a weak voice.

He could not see him anywhere and there was no answer. A squirrel jumped out of the tree and ran away.

“Billy!” called Little Joe, panic-stricken. Was he mashed underneath?

Then Dad was suddenly standing there beside him. He hadn’t heard Dad come up at all.

“Billy is …” Little Joe began. “He’s underneath.”

Dad pushed the branches aside. There was Billy underneath, laughing. He wasn’t hurt at all. He was only pretending.

“Let’s do it again!” cried Billy.

But Dad said no, he might get hurt.

Little Joe learned a lot from Billy. Billy took him for hikes in the woods, the dogs at their heels. There was big, old lazy Ringo, the cow-dog, part Collie; mean little Corky, half bulldog, half-terrier; and Rex, just plain cur. All the loggers had plenty of dogs and most of them were mean. Oregon was a country of big trees, big logs, and big dogs.

One day Little Joe and Billy came to a clearing of wild grass. They heard some yapping, but it was not the dogs. The boys stood still and listened.

“Gray diggers!” said Billy. “Let’s go up quiet.”

There they were, the digger squirrels. They were eating seeds off the wild grass. They were standing up, the tall grass between their legs. They filled the pockets in their cheeks with seeds.

“Cute little fellas, ain’t they?” said Little Joe. “Sometimes I see them at the barn getting oats, or under the big oak tree, munching acorns.”

“They got tunnels in the grass,” said Billy. “They make long runs and fill ’em up with acorns and seeds and stuff to eat in winter. Wish I’d brought my gun along.”

“What do you want to shoot ’em for?” asked Little Joe.

“Oh, just for the heck of it.”

Suddenly out from the brush jumped the dog Corky. Before either of the boys could say a word, he grabbed the biggest digger squirrel by the neck, as the others disappeared in the burrows.

Little Joe yelled and Billy grabbed at the dog. The dog dropped his prey. The squirrel lay on the ground, not moving. Little Joe brought it home on a stick, dropping it twice.

“It’s just knocked out,” he kept saying.

But it wasn’t.

“It’s plumb dead,” said Dad, when he met them on the path.

They made a hole and buried it.

“Corky’s worse’n a hawk!” cried Little Joe, furious. “I’ll beat the living tar out of him!”

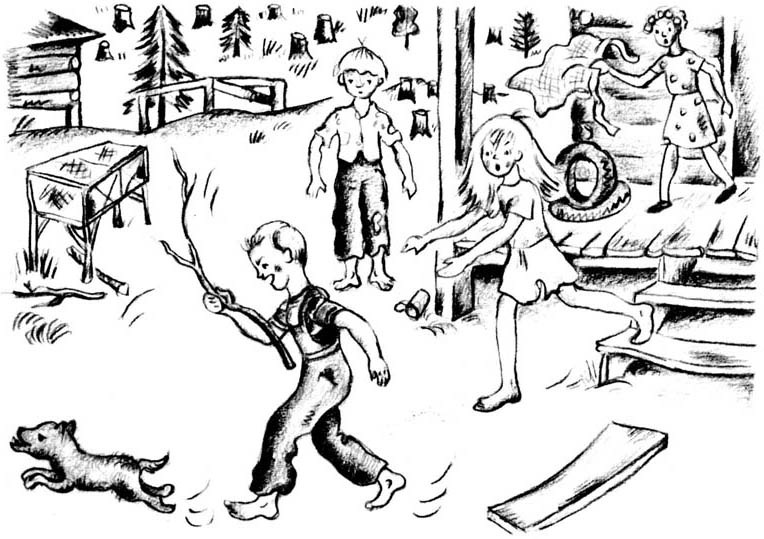

He found a stick and chased after the dog. The dog ran to the house, yelping as if he had been killed. What a coward he was, after all. His yelps brought the girls out of the house, screaming. Jinx, long legs and long hair flying, and back of her Sandy, red hair in curlers, waving one of Mom’s aprons.

“You’re cruel!” yelled Jinx. “Let my dog alone!”

“Don’t you touch Corky again or I’ll clobber you!” shouted Sandy.

Billy stood and watched, mouth wide open. He had no sisters, so did not know what to expect next.

Suddenly the rumpus was all over. The girls dropped Corky and went indoors. Little Joe went off with Dad to feed the hogs, so there was nothing for Billy to do but go home.

One day Little Joe and Jinx were loading house wood. Dad had falled a madrone tree, sawed off the limbs, bucked them in chunks, and split them. The children had to pile the wood in the pick-up. Madrone wood was good for firewood. It held the heat a long time and left few ashes.

Jinx was younger than Little Joe. Her hair was long and always in the way. She often wore shorts and a T-shirt. She was a tomboy and liked doing all the things Little Joe did.

“What we need is a donkey to load this wood,” said Jinx. She threw a piece of wood into the truck angrily.

“A donkey?” asked Little Joe.

“Yes,” said Jinx, “like the loggers have, to load logs.”

Little Joe stared at her. “Donkeys don’t load logs!” he said.

“Yes, they do, and so do cats!”

Little Joe said, “I don’t believe you.”

Jinx told everybody at the supper table.

“Little Joe says donkeys don’t load logs! And cats don’t either!”

They laughed, Dad most of all.

“I’m glad he don’t know,” said Mom. “There’s plenty of things he’s better off without knowing.”

Dad looked at his son, disappointed and a little sad.

“Son,” he said, “there’s two kinds of donkeys, and only one has four legs. Jinx meant the other kind. A donkey, to a logger, is a machine. So is a cat.”

Little Joe looked at the floor, ashamed.

“It’s time you went to the woods with me,” Dad said. “A good logger knows how to do anything in the woods. He can fall and buck trees, he can operate the donkey, the cat, or the shovel. He can top a tree and put up rigging. It’s time you learned about some of these things.”

Mom shook her head.

“I’ve lived all my life without seeing a logging operation,” she said, “and I hope I never will.”

But she did not say the boy could not go. She knew it would be a waste of breath. Big Joe was determined to make a logger out of Little Joe, no matter what.

Dad planned the trip the night before. He sent Little Joe to bed early.

“Wake up, Little Joe! You goin’ with me?” he called next morning.

It was still dark and Dad was calling. Little Joe opened his eyes and jumped into his clothes. Mom, half awake, was pouring coffee. The girls were still in bed. Dad was at the table, eating bacon and eggs. Little Joe stuffed food into his mouth quickly. He watched Dad put on his calk boots and his tin hat. Mom held out the lunch bucket, then went back to bed.

Next thing Little Joe knew, they were in the old rickety Ford bumping down the highway. A long ride down the twisty canyon road, with high rocky cliffs on one side and a steep drop down to Elk Creek on the other. At the corner by River Bend store and garage, Dad and Little Joe left the car and piled into the crummy. It was just getting light.

The crummy was yellow and looked like a small bus. It had seats facing the front, on both sides of a center aisle. It belonged to the Elkhorn Logging Company and was used to take the crew to work. Their cars were left parked by the garage.

The men piled into the crummy, laughing and joking.

“Little logger! Little logger!” they cried, teasing Little Joe.

“A chip off the old block!” they shouted, razzing Dad.

The road got bumpier and rougher as they left the River Road and entered the National Forest. The crummy wound in and around and up and down on a narrow trail through the mountains. Little Joe kept bobbing off to sleep and waking up again.

At last they got there and the men jumped out.

Little Joe got out, too, and looked around.

Dad showed him the big caterpillar tractor and told him it was called the cat. The choker-setter put a cable around a log and hooked it to the drawbar behind the cat. Then the cat-skinner pulled it to the landing.

It was fun to watch.

Little Joe knew now that cats and donkeys were not four-legged animals, but powerful machines.

At noon the whistle blew and the men stopped work. They sat in the shade and ate their lunch. They laughed and joshed each other. They teased Little Joe and predicted he’d be a better logger than his dad.

It was a long day for Little Joe, but one he never forgot. That night he was very tired, but his logging education had begun.

Now he wanted to be a logger more than ever.

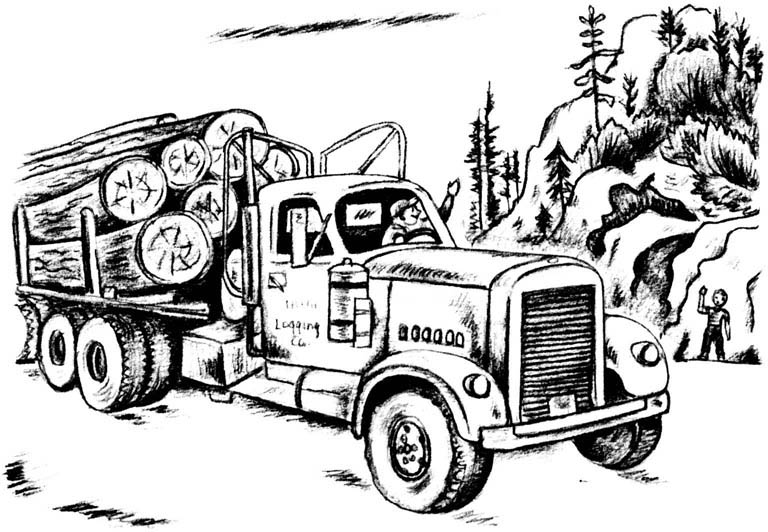

After that, every chance he got, he ran down the bumpy woods road to the highway. He wanted to watch the great logging trucks go by. The little creek crossed over the road in a culvert and emptied into Elk Creek back of the Drum Country Store. A great cliff jutted out into the highway across from the store, making a bad turn in the road. The trucks had to slow up going past.

Little Joe sat on a rock and waited. In the early morning, one truck came along after another. The men had all started loading at daylight. Each logging company had trucks of a certain color. Some were blue, others red, green, or yellow. Uncle Irv’s was orange. He was a gyppo trucker. That meant he was independent. He owned and drove his own truck.

Little Joe waited. He heard a loud grinding roar. He looked up the highway—a logging truck was coming. He watched as it came closer. Was it Uncle Irv’s? No, it was yellow.

He stood by the road and signaled, raising his arm, bent at the elbow. The driver answered, tooting his horn.

Whoo! Whoo! sounded the air horn. The truck drivers enjoyed signaling to small boys. Little Joe laughed.

What a huge thing it was! Sixty-five feet from front to back, carrying a stack of logs forty-eight feet long, resting on its trailer. Some of the logs were more than three feet in diameter. What big trees they must have been! Now they were on their way to the mill in town to be sawed into lumber. Round a bend, the truck was already out of sight, speeding along at fifty miles an hour.

Every time he saw Uncle Irv, Little Joe begged for a ride on his logging truck. When he was six, Uncle Irv took him for the first time. It was the biggest thrill he had ever had. After that, Uncle Irv took him often. He enjoyed the boy’s company, and the boy like nothing better.

Every time Billy Weber came over, the boys talked about what they wanted to do when they grew up. It was always logging.

“When I get big,” said Billy, “I’m gonna drive a cat.”

“When I get big,” said Little Joe, “I’m gonna drive a logging truck.”

“Joel! Come here,” Mom called one day.

He was always called Joel now, because he was twelve and growing up so fast. He had not been called Little Joe since he started to school at six years old.

“Take this letter down to the store and mail it,” said Mom. “Get two loaves of bread, a pound of oleo, and a large can of beans. Tell Myra to charge it.”

Joel snatched a biscuit off the table. He looked at the letter. It was addressed to Aunt Alice, Mom’s sister, in Rogue River, Oregon. What was she writing to her for? He jumped on his bike and rode down to the highway. His bike was an old one, rescued off a dump, but it was still able to go. It was faster than walking or running, even.

Joel went into the store. Myra Ross, the owner, was sitting on a stool behind the counter reading a book. She didn’t even look up. Joel went to the cubbyhole postoffice in the back and dropped the letter in the slot. Then he picked up his groceries. Bread from one shelf, beans from another, and oleo from the case. He plumped them down on the front counter and said, “Charge it!”

Still Myra did not look up.

Joel banged the can of beans down loudly and shouted, “I said charge it!”

Myra looked at him over her glasses and said softly, “I heard you the first time.”

“If you didn’t spend all your time reading books,” Joel said in a loud voice, “you’d be a better storekeeper.”

“That so?” asked Myra.

“Yes, and I mean it,” said Joel.

The door opened and Billy Weber came in. He and Joel were still the best of friends.

“What’s the matter with reading a book?” asked Myra.

Billy answered for Joel, “Loggers don’t need to read books. My dad said so.”

“Some loggers are afraid they might learn something,” said Myra. “Good thing all boys’ fathers are not loggers.”

The two boys looked at each other. What a funny thing to say. Everybody knew that dads were always loggers.

“My father’s a logger,” bragged Billy.

“So’s mine,” said Joel. “And so’s Jim Hunter’s and Snuff Carter’s and …” He rattled off the names of all the boys he could think of.

“But what about Andy Whitcomb?” asked Myra. “His father runs the River Bend gas station. And Roy Benton. His father brings the mail.”

It was true. The boys had never thought of it before. She was right. The danged woman was always right. Myra Ross was always jolting them somehow.

“There’s lots of things you could be,” Myra went on. “Doctors, lawyers, scientists, explorers, editors, merchants, storekeepers, mailmen, garage owners …”

Joel and Billy stomped out of the store angrily.

“Thinks she knows it all, that woman!” said Joel.

“My dad says she’s crazy!” added Billy.

Joel thought for a minute. “Is she?”

“Well, she’s got crazy notions,” said Billy, “and she don’t know beans about logging.”

“That’s right,” said Joel.

“Who’d want to be a mailman?” asked Billy.

“Or run a gas station?” added Joel.

“There’s only one thing to be,” said Billy.

“Loggers,” said Joel.

That ended the matter.