At first glance, some might feel that Larry David’s character on Curb Your Enthusiasm is highly neurotic, that his behavior is that of someone who fails to fit in with society’s norms and customs, or that he’s just being difficult for difficulty’s sake. If asked to provide a description of Larry, it wouldn’t be a stretch to reach for words like ‘anxious’, ‘anguished’, or ‘despairing’.

There’s lots of anxiety in Curb Your Enthusiasm. Think of the times when Larry hunts down a persistently annoying smoke detector, when he unleashes a lion-like roar as he tries to open the packaging on his new GPS, or when he has some sort of run-in with a bathroom or a toilet or a bathroom monitor. These are real moments of anxiety in our everyday use of the term. But existentialist philosophers have given this word an extra meaning, when they talk about existential anxiety.

Existential anxiety is the mood we arrive at when we realize that we are what we make of ourselves. We don’t receive our identities. We create them. In Curb, we find this type of anxiety when Larry has to make a decision, any decision. It’s rare that the weight of his deliberations is proportional to what we would consider their actual importance. Even the most seemingly trivial decisions are grave concerns for Larry: “Doctor? . . . Pharmacist? . . . DOCTOR? . . . PHARMACIST? . . .” The existentialist philosopher Martin Heidegger says that “anxiety can arise in the most innocuous situations.”1

In moments of anxiety, Larry realizes the extent of his freedom as a human being. The entire weight of the world, and the way that we’re immersed within it, bears down upon him. As he agonizes over his choices, Larry shows us that we’re forced to make a decision regarding the way we ought to live. True anxiety shows us just how alone we are when we have to make decisions.

The existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre uses the term “anguish” to refer to those situations. Why should seemingly minor decisions arouse “anguish” or “existential anxiety”? According to Sartre, we experience anguish when it dawns on us that we have the entire responsibility for our choices, and that in making these choices we’re saying that other people ought to be making similar choices.

Sartre says that when I act in a particular way, I am necessarily showing other people that I take that act to be of value to me. If we realized this before every decision we made, the decision’s importance would multiply. Anguish, then, is a mood that takes place along with this realization, and the pain it brings is the pain of knowing just how important our choices are. In the world of Curb, anxiety creeps in at these moments because Larry does not appeal to anyone else. He makes the choices by himself, and tends to take responsibility for them. As the exchange between Larry and the mother of Richard Lewis’ girlfriend goes:

DEBORAH’S MOTHER: We’re all responsible for our own lives.

LARRY: I think there’s some truth to that. (Season Three, “The Benadryl Brownie”)

Although we may suspect that Larry doesn’t believe Deborah’s mother actually thinks this, it’s still true that his recognition of our individual responsibility is present in most of his own decisions, and shows itself in his existential anxiety.

We define ourselves by the types of actions we choose to perform and the extent to which we accept responsibility for the choices in our lives. This is why we can say that Larry philosophizes with a 5 wood. In making the choice to take the golf club out of the casket, Larry’s action proclaims an image of right and wrong that he thinks everyone ought to find acceptable. He understands that it’s completely unacceptable in our society to steal from a dead person. To make this decision, then, Larry must decide for himself what he’s going to do. He must make a decision about what type of person he thinks everyone should be, and he confronts his dilemma with an argument. We can see his reasoning in this scene:

LARRY: That club’s irreplaceable. It’s ten years old. They don’t make it anymore.

JEFF: I’m so sorry. I’m sorry man . . .

LARRY: Why should this guy be buried in eternity with my club? That’s not fair. (Season Four, “The 5 Wood”)

If there were a fixed essence for human beings, LD could appeal to it. Knowing the essential nature of humans could help him figure out what to do in this situation. If the existentialists are correct, however, there isn’t any fixed model of humanity to guide us. Larry assigns value to this action, and makes the decision all alone in the face of ordinary funeral etiquette. While Jeff’s apology demonstrates that he expects Larry to just leave the club behind, or shows that that is what he would do, Larry tackles this as a decision head-on.

According to Heidegger, real anxiety is not the type of feeling we have when we are being chased by an angry mob (when, for example, we have stolen a Joe Pepitone jersey from someone). That feeling is caused by something very specific. Anxiety is more general. As Heidegger once put this point, while fear has an object, anxiety concerns itself with “Nothing.” In the tradition of existentialism, anxiety is not the kind of emotion that leads one to scream out or pound one’s fists on a table. Rather, “a peculiar calm pervades it.”2 Existential anxiety involves coming face-to-face with the realization that we’re in charge of deciding what will be done with our lives. It’s when we confront the immense responsibilities inherent to the human condition that we are truly anxious.

While in the car with Loretta in Season Seven, Larry goes out of his way to make himself seem like a bad person. As viewers, we know that his motive is to encourage Loretta to break up with him. At this moment, though, Larry offers up a surprisingly candid description of himself that cuts to one of the core aspects of both existentialism and the show as a whole:

LARRY: Some people are nothing even with health. I fall into that category sometimes. A nothing—a big nothing—and I have health. (Season Seven, “Vehicular Fellatio”)

If there’s something more to this claim than his desire for Loretta to break up with him, existentialism provides us with one of the clearest ways of interpreting it. Sartre claims that, “If man, as the existentialist conceives him, is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be.”3 We are not born as nothing in the sense that we have no bodies, or that we arise from situations that are culturally and politically neutral. We are originally “nothing” in that the way we make sense of ourselves and go about our decision-making processes will be entirely up to us as free individuals. We are “nothing” because we have to make ourselves into the people we want to be through our own volition.

If our individual actions are what define us, then it’s against the background of those actions that an existentialist philosopher would claim we should judge others. Larry’s critiques of others follow this same logic. He doesn’t merely take jabs at people for being of a certain race, sex, or religion. He usually makes fun of people for the choices they make, for the way they choose to think of themselves, and for the values they espouse, which are often arbitrary or self-contradictory. He gets angry with Andy for choosing to order crispy onions, harasses Richard’s girlfriend for not giving him enough space to maneuver in the theater, and is sickened by Jeff’s sexual fantasies because they involve Cheryl. When people make decisions that Larry dislikes, he tends to be honest with them about his disdain.

There are, however, instances when Larry goes out of his way to lie to people. When conversing with a friend in a wheel-chair, he says that he doesn’t enjoy playing golf, and that he really just enjoys sitting around all day. When Cheryl asks him to dance with her in the company of a widow, he says that he can’t, so that he doesn’t remind the woman that her husband isn’t there to dance with her. In these instances, Larry is very aware of the presence of others, and he acts accordingly. He acts the way he wants to be perceived. While some of his lies are simply self-serving, he often tells lies because he doesn’t want to draw attention to other people’s limitations as long they are beyond the person’s control, as disabilities and tragedies are.

Facing the charge of having proclaimed a philosophy that could only account for one individual human being apart from the society that person lives in, Sartre replies by saying:

When we say that man chooses his own self, we mean that every one of us does likewise; but we also mean by that in making this choice he also chooses for all men. In fact, in creating the man that we want to be, there is not a single one of our acts which does not at the same time create an image of man as we think he ought to be. (p. 17)

Larry thinks we all ought to be like him, that we ought to live our lives and act in accord with his values. While existentialism doesn’t tell us to follow the specific rules that Larry chooses to defend (I don’t know of any report that Heidegger or Sartre commented on the proper amount of caviar to consume at a party), it does provide a philosophical foundation for his behavior.

Existentialism often gets a bad rap. Existentialists are usually portrayed as wearing all black, sitting in dark cafes, drinking copious amounts of espresso, and contemplating the nature of death from behind bloodshot eyes. While this is a misleading caricature, there’s some truth to the idea that existentialism concentrates on very serious issues, as we often hear people refer to “existential crises” when their life projects have been halted or called into question.

In its shortest formulation, existentialism can be expressed by saying that for human beings, “existence comes before essence,” meaning that we must first act in a particular way before we can be defined (p. 13).

To see what this means, consider a designer who’s drawing up plans for a tool such as a screwdriver. When we look at a screwdriver it’s clear that it was produced for a specific purpose. There is an essence of what it is to be a screwdriver, and this involves being capable of turning screws well. Once the designer has made the specifications so it can be manufactured, the essence of the screwdriver is already in place. The essence is in the specifications before the screwdriver is actually produced. When the screwdriver is finally completed, its essence will be the same as it was when it was still an idea in the designer’s head. The screwdriver’s essence is fixed and the screwdriver doesn’t get any say in the matter.

Now consider parents who are attempting to map out the life of a soon-to-be-born child. They might think they can take the same approach as the screwdriver designer, laying out plans on paper, and sketching out the intermediate steps needed in order for the child to become, say, a doctor or a lawyer. If the child were the same type of thing as the screwdriver, there’d be no problem. Problems arise, however, because the child will have drives and desires of her own, and will be capable of choosing a different life for herself if being a doctor or a lawyer is not what she wants. Think of the time when Larry tries to convince his nephew that he’s not really a magician. As much as Larry wants to be able to dictate his nephew’s identity, the matter is out of his hands. The nephew makes the choice to disregard Larry.

Sartre’s claim is that human beings are very different from things like screwdrivers. For human beings, the type of creatures we are will only be defined by the way we act. We will be defined by the type of existence we freely choose to lead. Each individual, each and every person capable of saying “I,” is the starting point for the person they are and who they will become. When it’s time to make a decision, we can ask for the opinions of others to aid in our decision-making process, but at the end of the day we have to make choices for ourselves.

Existentialists claim that each individual’s personal identity is actively determined by the sum of all of their actions. If this is true, there is no fixed human nature we could appeal to in describing ourselves. When a couple of “survivors” get into a fight and spill gravy on Larry at a dinner party, Cheryl’s mom suggests that someone should grab him a sponge to clean up the mess. In a classic existentialist manner, Larry replies, “I don’t understand. . . . Why don’t you get a sponge?” Each of us is put in such a position that we must choose who we are going to be, and make ourselves through the actions we perform. Feeling or thinking that something ought to be done doesn’t cut it.

This means that we’re given a huge responsibility in deciding who we are and how we ought to live. Someone might say, “Existentialism can’t be right. This isn’t how most people live their lives.” But philosophers like Heidegger and Sartre would agree. They would concede that it’s rare that we take the time to fully reflect on each and every decision we need to make in our lives. However, there is still a sense in which we could live like this, if we were being completely honest with ourselves all of the time, and we weren’t making excuses for our failures.

When we’re completely honest, there really are no excuses, as Sartre puts it. We can always make different choices, even if those choices are only about the attitudes we adopt toward circumstances beyond our control. Living honestly means living authentically, and to live authentically means to completely own-up to all aspects of our lives within our control. Existentialism is an extremely demanding philosophy. The responsibility we have placed upon us due to our freedom is what leads us to the feeling of existential anxiety, and Larry is a prime example of its sway.

If Sartre’s right, then we don’t need to be paralyzed or saddened by the freedom he claims we have. Sartre thinks we should enthusiastically embrace his philosophy. It’s not just the big issues in our lives that require us to make large decisions. Even the smallest of choices demands our careful attention. Larry takes up the same approach on Curb. For him, there is no meaningful difference between religion and lobster, or between a doctor’s diagnosis of cancer and a discussion about the benefits of keeping fish as pets. And there seems to be no greater value than those expressed in the complex economy of golf tips.

This shouldn’t surprise us anymore. If our lives are defined by the choices we make, then even the most mundane aspects of our lives become the subject of intense contemplation. Each and every choice we make calls us to assert ourselves through our own free will, since the existentialists claim there are no values apart from the ones we adopt in our decision-making.

Some people say that existentialism is too pessimistic, that it highlights only the ugliest portions of human existence (such as anxiety or despair), and that it ignores the things that allow us to experience happiness. A common reproach aimed at individuals who are seen to be anxious or despairing is the imperative to “Just be happy!” or to “Quit over-thinking things!” Larry is often in situations that might lead people to offer the same advice. We might want him to relax, and not call every tiny aspect of his daily routine into question. Is it true, though, that Larry merely finds the bad in everything? Is he too pessimistic?

Maybe the opposite is true. Maybe Larry is actually quite the optimist! If there’s no given purpose for human beings, we can use our own free actions to provide the world with value, or to show that some of society’s rules shouldn’t be followed. To find faults within society in the Larry David fashion requires commitment. We have to be committed to changing the world, even just little parts of it, instead of merely passing them by and accepting the status quo. A pessimist would see things in the world that need to change, but wouldn’t consider herself capable of changing them. If she thought a particular practice was etched in stone according to a fixed human nature, she wouldn’t even try to change it. As Larry says to a receptionist,

LARRY: Things like this interest me. I’m not an inventor, but I’m an improver. I improve things that are broken. This is broken. This system is broken; I would like to improve it. (Season Six, “The Bat Mitzvah”)

In this case, most people would either not even notice a minor inconvenience related to the bureaucratic tendencies of a proctologist, or notice them but say nothing at all (why draw more attention to ourselves when at a proctologist’s?). Larry, however, commits himself to changing the way the waiting room operates, demonstrating that he’s optimistic enough about the things he’s capable of affecting. He’s optimistic about the extent of his freedom. If he doesn’t say anything, who will?

In response to some of his critics Sartre claimed: “When all is said and done, what we are accused of, at bottom, is not our pessimism, but an optimistic toughness” (p. 33). It’s not that the existentialists are accused of being too sullen or angry, but that they are often disliked for reminding us that we have more responsibility than we thought. The angry reactions Larry tends to get from people usually aren’t directed toward some definitive flaw in Larry’s revelation, but toward the toughness associated with his rocking the boat. An object at rest tends to stay at rest. People would rather not think about what they’re doing or thinking. They’d prefer to just do it or just go on thinking it. But nothing is that easy with Larry. He doesn’t take anything for granted.

For both Heidegger and Sartre, we usually flee from the most important aspects of our existence and take refuge in the tranquility of what’s easy and familiar. Heidegger called this our everydayness, the way we exist when we’re living the lives that everyone else thinks we should. We avoid confronting the issue of our freedom. We deceive ourselves. Sartre referred to this aspect of our lives as our living in “bad faith.” We trick ourselves into the belief that we are incapable of making all of the choices dictating the course of our lives. To live in “bad faith” means allowing ourselves to go about our day while avoiding taking responsibility for everything that we can.

Larry calls people out when he suspects that bad faith is operative. For example, when he tries to get Susie’s brownie recipe, he’s confronted with her reluctance to hand it over. She repeatedly claims that she can’t, that the matter is out of her hands and she is unable to act otherwise.

LARRY: I would love if you could give me the recipe.

SUSIE: The brownie recipe? I can’t do that, darling. I can’t.

LARRY: No, no. What do you mean? Of course you can. (Season Three, “The Benadryl Brownie”)

Larry gets angry when he hears this, because he thinks Susie is deceiving herself. Of course she can give him the recipe. What she can’t do is simultaneously respect her grandmother’s wishes that the recipe remain a secret and give it to Larry. As long as Susie says that she cannot give Larry her recipe, she’s fleeing from the responsibility of owning up to her commitment. She’s avoiding the freedom existentialism tells her she has. The role of dispelling people of bad faith and pushing others to take responsibility for their lives is one that Larry plays often on Curb.

In existentialism, the concept of bad faith is closely related to the concept of authenticity, which is another topic that occurs again and again on Curb. Consider Larry’s attitude toward his own baldness, and the standards to which he holds other bald people. Larry’s baldness is an attribute that he is very proud to display. He doesn’t attempt to hide his baldness with hair plugs, toupees, or hats. His approach to his own baldness exhibits authenticity in the existentialist sense, because it involves being honest with himself and owning up to certain facts about his body and appearance. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t authentic toupee-wearers or authentic hair-pluggers. Someone could alter his follicular situation and remain authentic so long as he openly identified with his choices in an honest way.

The issue of inauthenticity and baldness, however, is exhibited clearly in Season Three when Larry meets a potential chef, Phil Dunlap, for the restaurant he is investing in. While Larry interviews Phil, he is extremely pleased to find out that he is also bald, and that he shares his views regarding bald men who try to hide their baldness.

LARRY: Toupée?

PHIL: No. Oh, no. Absolutely not.

LARRY: Those guys. They should kill those guys.

PHIL: Exactly.

LARRY: I’m surprised Hitler didn’t round up the toupée people. (Season Three, “The Grand Opening”)

As the scene proceeds, Larry continues to express his disdain for people who attempt to cover up their baldness, and Phil agrees with him the entire time. Later in the episode, when Larry discovers that Phil actually does wear a toupée, he fires him on the spot. Phil was inauthentic because he was hiding who he was. We’re not responsible for the genetic makeup we’re given, but the existentialists claim that we are responsible for our attitude and honesty regarding what we find ourselves with. As Sartre says,

Man is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet, in other respects is free; because, once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does. (p. 23)

At a minimum, Phil should have defended toupées during his interview. If it’s our actions that define who we are, and not merely the private thoughts we keep in our heads, Phil had a responsibility to own up to his choices.

Sartre asks his readers to imagine a voyeur who is peeping through the keyhole of a closed door. While watching, the voyeur’s consciousness is completely directed to whatever’s taking place on the other side of the door. But, Sartre says, imagine what happens to the voyeur the moment he thinks he hears someone behind him. The sound brings him away from what he has been viewing, and makes him aware of himself as an object that can also be viewed. Sartre’s example shows just how profoundly our consciousness is at the whim of how we think others might be gazing at us.

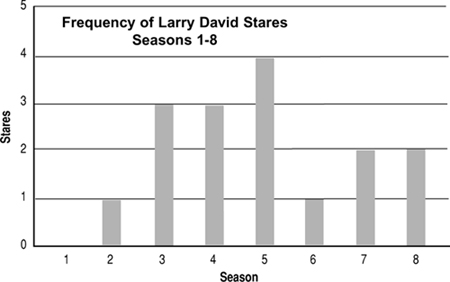

Existentialism’s philosophy of society is demonstrated on Curb through the “Larry David Stare.” The investigative stare that Larry subjects his interlocutors to is an attempt to glean the truth somehow in the eyes of the other. It usually takes place when one person (usually, though not always, Larry) suspects another person of telling a lie. As the scenes play out, aided by frolicking horns, Larry maintains eye contact while tilting his head one way and the other, attempting to find the magic perspective that will allow access to the thoughts of the other. After about ten seconds, we inevitably find that Larry retires with an unconvinced and still suspicious “Okay . . .” In these moments, we see Larry trying to know everything about another individual, but then running up against the impenetrable boundaries inherent to another person’s private thoughts.

We may have our suspicions about behaviors others have exhibited in the past, questionable actions, or other motivations (“There’s something about that weatherman I don’t trust. I don’t like that weatherman. He’s a very slick weatherman.”), but what Larry shows us is that at the end of the day we must relinquish our attempts at complete mastery and recognize those things we actually have control over. Coming to realize that we cannot know all of someone else’s thoughts or that we cannot completely control how others view us, both Sartre and Larry David claim that we must continue to act in such a way that we assert our values. We must act in ways that demonstrate how we think all human beings ought to live.

Sartre finds “The Look” of the other to play a huge role in our subjectivity, and the “Larry David Stare” plays an equally potent part in the constitution of many of the characters. While being stared down, the victim of the stare often looks quite nervous, knowing that he has been called out and put on the spot. In the face of the other, we realize that we’re not the only ones experiencing the world, and that we’re essentially sharing the world. For Sartre, “it appears that the world has a kind of drain hole in the middle of its being and that it is perpetually flowing off through this hole.”4 As the “Larry David Stare” theme music plays, any attempt to retreat into a solitary existence is removed, and the “drain hole” of Larry’s squinting eyes aid in the constitution of his victim’s personal identity. While under Larry’s gaze, something fundamental about his victim’s consciousness is altered. They’re reminded that they are always potentially being watched.

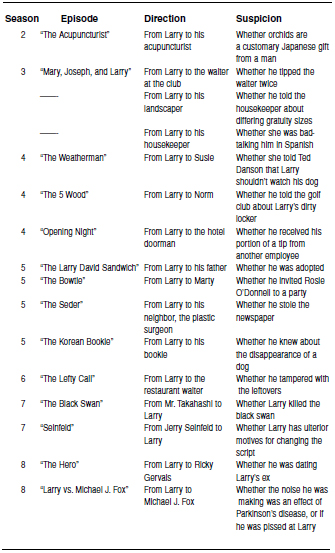

Curb Episodes Featuring the “Larry David Stare”

The stare represents an attempt to treat human consciousness as something that could be viewed empirically and catalogued in the same way a scientist would observe forces and material substances. It’s no surprise, then, that there never seems to be any success to the Larry David Stare. If Sartre is correct that our subjectivity exists only for the private view of the individual in question, then it could never be the case that a stare could cut to the subjective truth of someone else, no matter how much one squinted. Because human beings are completely free, and thus always more than whatever they are at a given moment, there is nothing in or about them to be looked at that could completely capture their consciousness.

Larry isn’t always on the sending side of the Stare, especially in the context of existentialism. After he kills the swan that belonged to the country club owner, Mr. Takahashi stares down Larry to attempt to force a confession. When Larry starts making changes to the Seinfeld reunion show script, Jerry Seinfeld performs the Stare on Larry to make sure Larry isn’t withholding any information from him. This shows us that he too is aware of being subjected to the gaze of another person, and that this is one of the fundamental aspects of our lives as human beings.

While we might think that being preoccupied with what other people think of us is overly vain, Sartre is suggesting that it’s an unavoidable part of our existence. Think of the predicament Larry finds himself in when he complains about the New-York-Yankee-hating stonemason who is, unbeknownst to Larry, standing right across from him. While he’s venting to Marty about the stonemason’s unforgivable hatred of Derek Jeter, his worldview is arranged in a somewhat harmonious way. He is merely having a conversation with a friend. However, when he discovers that the villain of his narrative is standing in the same conversation circle, the harmony is disrupted. While nothing seems to have changed materially, the recognition of the stonemason’s presence in the conversation immediately changes Larry’s situation. He gets embarrassed. For Sartre, this type of feeling is entirely inevitable in society. As he says,

Thus suddenly an object has appeared which has stolen the world from me. Everything is in place; everything still exists for me; but everything is traversed by an invisible flight and fixed in the direction of a new object. The appearance of the Other in the world corresponds therefore to a fixed sliding of the whole universe, to a decentralization of the world which undermines the centralization which I am simultaneously effecting. (Being and Nothingness, p. 231)

While some of Sartre’s language can be disorienting, the take-away point is that we are made to feel very strange in the presence of others. This happens merely by our recognition that someone is watching.

What, then, have we learned about Larry David? If there is something like a Larry David essence, what we glean is not the product of one man instilled with a particular set of unchanging traits. What we have is an individual who perpetually chooses to live a life that exhibits what he holds to be valuable. This is done even though it repeatedly leads to existential anxiety, and must be done while being subjected to society’s stares. There isn’t a Larry David essence in the sense the philosophical tradition has given it, but a particular existence or style of existing based on the actions of a man who experiences genuine anxiety in the face of most choices.

The imperative put forth by the series title to Curb Your Enthusiasm ought not to be understood as a call to be unhappy, or to only find the bad things in our lives. We should not merely reduce the level of our enthusiasm. It’s better understood under the optimistic conditions that existentialism provides us with, meaning that we can take responsibility for what we enjoy, and that we do this by authentically connecting with the things that matter to us. By curb-ing, we’re invited to lead lives in which we authentically choose what is worth being enthusiastic about, and what is merely given to us by society as something that ought to be enjoyed.

It’s unfortunate that existentialism gets a bad rap, but by carving off the excess of our inauthentic enjoyment, what we’re left with is an optimistic and enthusiastic existence that will be continually renewed in the face of anxiety through our actions. Larry David: existentialist, anxious, and optimistic. The only question we’re left with, then, is “Why don’t you grab a sponge?”

1 Being and Time (Harper and Row), p. 234.

2 “What Is Metaphysics?” in Pathmarks (Cambridge University Press), p.88.

3 Sartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions (Kensington), p. 15.