This chapter will take you through the key elements of the cognitive behavioral model and then highlight how this may be applied to your own situation. The chapter ends with a brief overview of the main issues that can be targeted with techniques derived from cognitive behavior therapy (CBT).

In the first chapter of Part One we noted that the thoughts (or images) that go through an individual’s mind largely determine their emotional response to an event. We also explored how events, thoughts, feelings, and behavior are linked together. When we went on to review the causes of bipolar disorder, we found that an individual’s beliefs about themselves and their world influence which life events are stressful to them. Then, in the last chapter, on treatment, we noted that an individual’s attitudes and beliefs about medication affect their adherence to treatment.

The term “cognitive” is often used to describe these thoughts and beliefs. Both are key components of the model of mood disorders.

Our beliefs usually develop during childhood. We start to develop a set of rules for living from how people act or react toward us, or from what we learn by observing other people’s interactions. The attitudes and beliefs of family members, school friends, teachers, and other people in our community also influence our early learning experiences and start to shape what we believe about ourselves and our world.

Even in infancy we start to notice repeated patterns in the responses and attitudes of others. These patterns influence the beliefs we develop. Most of the beliefs we hold are quite adaptive, that is, helpful in guiding our attempts to be considerate and well-balanced individuals. However, some individuals’ experiences during this early stage of their cognitive and emotional development may lead them to evolve rules that are maladaptive (dysfunctional) and have an unhelpful influence on how they act and react. Here are some examples that illustrate this point.

Judith is ten years old. She lives at home with her parents but her father, a successful businessman, often has to travel away from home. Judith has been doing very well at school, much to the delight of her father. At the end of the school term, Judith returns home with a glowing school report. She has grade As for all subjects except mathematics, where she achieved a B grade. She is keen to show the report to her father. He eventually returns home – late, tired, and somewhat preoccupied with a meeting he has to attend early the next day. He opens Judith’s report, glances through it and then says: “Your grade for mathematics is a bit disappointing, what happened there? It’s a shame it’s your weakest subject, some people say that maths is the best measure of a person’s intelligence. Oh well, you’ll have to try harder next time . . .”

Over the next year Judith works hard at mathematics. At times she feels rather anxious about her ability to do this subject, but her teacher is encouraging and seems pleased with her work. At the end of the year she returns with her school report. Judith has a grade A for mathematics. Her physical education teacher (new to the school that term) has given her a grade B (the report does not show that this is the top mark this teacher gave; the rest of Judith’s classmates got a grade C). Judith’s father examines the report. He says nothing about her grade A in mathematics, but then says: “Shame about your physical education mark. School isn’t just about being a good academic, you know; a fit and healthy body is just as important as a sharp mind.”

This scenario is somewhat artificial, as it does not describe other aspects of the intervening period in Judith’s life. However, on the basis of the information given here, consider two issues. What beliefs do you think Judith might have developed about herself through these experiences? What might she decide she has to do in future to be valued by other people?

The ideas that you might identify include “I’m not good enough,” and silent rules such as “In order to be liked/loved, I have to be successful in everything I do.” If Judith did grow up with these beliefs, how might she react as an adult if she failed to get an expected promotion at work?

John is an only child of seven years of age who lives with his parents. For as long as John can remember, home has not been a happy place: his parents are constantly shouting at each other and his father has left to live elsewhere for a while on two previous occasions. Each time his father has left, John has had no idea why his father has gone or if he will return. Neither of his parents has discussed these departures or any other issues with him. However, at various times John has been shouted at, ignored, and/or neglected by his parents.

What beliefs might John have about himself if he was shouted at, ignored, and/or neglected? Given that his father left home twice without indicating when he might return, what beliefs might John develop about other people?

John’s beliefs about himself could include: “It’s my fault,” “I’m not important,” or “I’m unlovable.” With regard to other people, John may develop beliefs like: “People will leave me,” or even “People cannot be trusted.” If these ideas are accurate reflections of John’s beliefs, how might he react in adulthood if his first serious girlfriend leaves him?

Taking the child’s-eye view It may take some time to grasp the ideas discussed in these examples, particularly as you need to remember to put yourself in a child’s place and to understand what they would make of these situations. They do not have the wealth of experience and knowledge that you, as an adult, have accumulated. They are unlikely to make sophisticated judgements about the adults involved in the scenarios. Also, a child is rarely in a position to demand an explanation of what is happening; if no one tells them what is going on, they have to draw their own conclusions.

It is important to note that fixed, maladaptive beliefs do not tend to develop on the basis of a single incident, but most often evolve from repeated exposure to similar situations. In rare cases, however, a single event has such a powerful effect that it alone shapes a person’s beliefs about themselves or other people. On a more positive note, the environment in which an individual grows up may also include protective factors (for example, a parent, grandparent, or teacher who is supportive). So, even if an individual is exposed to adversity, they do not always grow up with low self-esteem or unreasonable expectations of themselves.

As observers of the above scenarios, it is easy for us to pause and reflect on the interaction between individuals, to take a balanced view of the information (evidence) available, and to view these incidents within a broader context of life experience. However, an observer has the advantage of being distant or detached from what is happening. If you are the person in the middle of a situation, it is not always easy to take a step back and look at it in a wider perspective: we often seem to react spontaneously or automatically. Our beliefs have influenced us for so many years that we are not usually aware that they drive our thinking (and thus our moods and actions). Not only do we fail to notice them operating, we never seem to question whether they are accurate or realistic.

The best explanation of how to understand the influence of maladaptive beliefs on a person’s life was put forward by two cognitive therapists called Christine Padesky and Kathleen Mooney. They suggested that you should think of a maladaptive belief as a prejudice you hold against yourself. People who hold prejudices are blind to how unrealistic or irrational their belief is, but it does influence their lives. For example, some common cultural stereotypes are that Americans are loud, and that the English are “cold fish” or “rather aloof”. Comments along these lines may seem amusing, but supposing an individual has grown up with a strong belief that the English are aloof and unfriendly and holds a prejudice against English people. If they meet some English people who are not very friendly toward them, what would they conclude? Most probably, that they were right all along. Furthermore, they now have evidence to reinforce their prejudice.

Now let us suppose the same individual meets a group of people at a party who are fun-loving and very friendly and welcoming toward – and they turn out to be English. How does the person with a prejudice against English people maintain their negative view in the face of this contrary evidence? The classic pattern is that they:

• fail to register that the people are English (don’t notice it),

• make excuses such as suggesting the English people were behaving differently because they were on holiday (discount it),

• tell themselves that, as some members of the group had Scottish and American relatives, maybe they were not genuinely English (distort it),

• simply state that this group “are the exception that proves the rule” (make an exception).

This example shows that if a person holds a prejudice (a rigid, maladaptive belief), they readily accept evidence that confirms their view. However, when they come across contrary information they ignore it or, without realizing, begin to adapt (distort) it so that it too fits with their belief system.

How prejudiced beliefs can work against you Having explored the principles of how prejudices operate, let us apply these principles to the underlying beliefs that individuals hold about themselves.

Imagine a person’s early childhood experiences led them to conclude that “I am not likeable.” This belief (self-prejudice) may lead them to avoid social interactions, so that they are rarely exposed to evidence either to support or to refute their idea. If they are unfortunate enough to encounter someone who dislikes them, then their belief is reinforced, their mind is filled with negative thoughts, and they may begin to feel sad. What if someone is nice to them and seems to like them? How do they react to this event? Sometimes they do not notice that the person is being kind. If they do notice, they may briefly feel happy, before doubts begin to enter their mind. Typical thoughts reported by such individuals include: “They are only doing it because they feel sorry for me,” or “They probably won’t like me when they get to know me.” The person once again begins to feel sad. For some, these doubts may also influence their behavior, for example, preventing them engaging in social activities with a potential friend. Their self-prejudice has won again.

It is important to stress that only very rigid, unhelpful beliefs are likely to lead to problems. For example, a certain degree of perfectionism may help us to perform tasks to a desired standard. However, a fixed belief that, “Unless I do everything absolutely perfectly, then I am a failure” can obviously put a person under a great deal of pressure. It may inhibit rather than encourage them to achieve what they set out to do, and they may perceive evidence of having “failed” across a variety of situations – at work, at home, or in personal relationships. For a perfectionist, even relatively minor events that many other people would regard as unimportant irritations can be significant stressors. If the individual is also vulnerable to a mood disorder, these stressors may push them into a vicious downward or upward spiral.

Changes in mood may also change what aspects of ourselves or our environment we attend to, and this may activate an underlying belief. For example, if a person feels depressed, they will tend to notice how they keep failing to live up to their perfectionist standards. If a person is going high, they focus on their perceived achievements (e.g. producing a large number of business plans for schemes they wish to undertake), while at the same time, failing to attend to evidence that suggests they are not perfect (e.g. some documents are incomplete, or the schemes are unlikely to be financially viable).

As well as a degree of perfectionism, other common themes in the beliefs of individuals who experience mood swings are a desire to be approved of by other people, and a wish to be in control of their lives and important situations. These beliefs are not unique to individuals at risk of mood disorders: similar ideas are very common in the general population. However, knowing what types of beliefs you hold will give you clues as to how you may act or react during upswings or downswings. For example, if you like other people to approve of you, when you are depressed (mood) you may worry that you are not liked (thought) and avoid people (behavior). When you are high (mood) you may seek out the company of important strangers (behavior) because you think they will strongly admire you (thought). If you wish to be in control, depression may be associated with a sense of powerlessness as you constantly feel that you have no influence over events; when you are high you may become angry or irritable with those who try to prevent you pursuing risky ventures.

Are you prejudiced against yourself? To begin to get a sense of your underlying beliefs, try to complete the following three sentences (again, this idea comes from Padesky and Mooney):

“I am . . .”

“People are . . .”

“The world is . . .”

Try to use a single word, or the minimum number of words you can, for each belief. Beliefs can usually be captured in one sentence rather than a paragraph.

Do not worry if this task seems difficult at this point. As mentioned previously, we are often not aware of our underlying beliefs, as they operate as “silent rules” in adulthood. This is particularly true when in a normal mood state. If you did manage to complete the sentences, you may wish to pause and consider whether you have noticed the influence of any of these underlying beliefs on your recent actions or reactions.

The relationship between automatic thoughts and underlying beliefs Underlying beliefs are present throughout our lives and operate across a variety of situations. A particular maladaptive belief will be activated by events that have some connection with the belief. For example, a silent rule that “I am not likeable” may become activated by the break-up of a personal relationship or by receiving negative feedback from a work colleague. The immediate (or automatic) thoughts that we have about each event or experience apply to what is happening there and then, and help dictate our emotional response at that moment.

A key characteristic of automatic thoughts is that they are “situation specific” – that is, the exact same thought does not usually recur again and again in different environments. However, there may be a common theme that links the thoughts together. Identifying this theme may provide important insights into an individual’s underlying belief. For example, a person who is vulnerable to anxiety may find a number of situations difficult. They may find flying in an aeroplane is associated with anxiety, because of thoughts such as “The plane may crash.” They may find walking a short distance on their own late at night equally anxiety-provoking, because of thoughts such as “Somebody may attack me before I get indoors.” The thoughts are unique to the event; but the common underlying theme is that the person regards the world as a potentially dangerous place. Their reaction to perceived danger is anxiety. Furthermore, the level of anxiety that a person experiences in response to such thoughts may prevent them doing things, such as going out on their own.

Types of automatic thoughts Individuals who are depressed find that their automatic thoughts are dominated by themes of loss and failure. They view themselves as weak, they see their world as full of negative events, and they are drawn to information that they think demonstrates that their future is bleak. This negative style of thinking about themselves, their world, and their future (called the negative cognitive triad) further increases feelings of depression and helplessness, and will often lead them to avoid potentially uplifting situations. Thus automatic thoughts powerfully affect the individual’s quality of life; and yet, these negative thoughts are often inaccurate interpretations and represent a selective view of the available information.

It is important to emphasize that this “tunnel vision” is not deliberate. All of us have automatic thoughts in response to the situations we encounter, and many of these thoughts are accurate interpretations, but some are not. We do not pick and choose when to distort our experiences. However, if our thinking is distorted it tends to promote more extreme emotional responses to events or situations. Automatic thoughts occur at a conscious level, but many individuals only become aware of their thoughts after they have learnt to focus on what goes through their mind if their mood changes. Once unhelpful automatic thoughts are identified, it is possible to modify them with resulting benefits for mood and behaviour.

Although there are differences in the automatic thoughts that individuals report, the types of thinking errors that occur (sometimes called cognitive distortions) are surprisingly consistent. Individuals may record that they have a set pattern of distorted information processing (e.g. always jumping to conclusions), while others find that their thinking shows many different errors. Some of the most commonly reported thinking errors are described below. You may like to assess whether you have ever thought in any of these ways:

• All-or-nothing thinking (extremism) Do you ever look at things in black-and-white terms? Is there any room for doubt, or do your self-statements demonstrate an extreme view of the world? Can you cope with the “grey area” in the middle where things are neither brilliant nor dreadful? Examples of extremism include: “It’s absolutely awful,” “It’s totally perfect,” “That should never happen,” “You must always get it right.”

• Overgeneralization Do you ever come to sweeping conclusions based on one minor event or a small piece of a larger puzzle? Do you ever assume that if something happens once, it will always happen? If so, you may be engaging in overgeneralization. Examples of such statements are: “I’ll fail the entire test,” “I’m too quiet, people will never like me.”

• Maximization and minimization Do you find yourself putting huge emphasis on either the strengths or the weaknesses of a person, or the good or bad features of an idea? In depression, people exaggerate the importance of minor flaws, making statements such as “I’m ignorant,” or underestimate their qualities: “They’re mistaken, I’m not really a generous person.” In contrast, when individuals are high or elated, they overestimate the gains and underestimate the losses associated with their ideas: “I can’t go wrong,” “They’ll love it.”

• Mind-reading Are your moods or actions ever influenced by a belief that you know what other people are thinking about you? In reality, we may have a general idea about what a person might think, but we do not have any special powers that let us know exactly what is going through their mind. However, this thinking error is very common and can cause distress. Examples of mind-reading error are: “She doesn’t like me,” “He only said that to make me feel better.”

• Jumping to conclusions Do you ever try to guess how things will turn out in the future without weighing up the evidence? When individuals are depressed they tend to predict negative consequences and assume catastrophic outcomes, making statements like: “I know it’s going to be awful,” “Things are bound to go wrong.” Alternatively, when individuals are elated they may predict everything will be wonderful: “If I give up work and buy a boat, I’ll be happy for ever.”

• Personalization Do you find yourself tending to take responsibility for everything, particularly blaming yourself for things that go wrong? Classic self-statements reflecting this cognitive distortion are: “It’s my fault,” “I’m a bad father.”

Having noted the different thinking errors, it is worthwhile trying to recall any thoughts that went through your mind when you experienced a recent noticeable shift in your mood. Can you write down your mood state then, and any of your automatic thoughts? If you can recognize and record any of your automatic thoughts, is there any evidence of cognitive distortions? For example, personalization may generate guilt; jumping to conclusions about the future may spark off anxiety; all-or-nothing thinking may be associated with depression; mind-reading that another person is not going to treat you fairly may give rise to anger.

Automatic thoughts and underlying beliefs are the key cognitive elements of the model of mood disorders. They are intimately linked with changes in mood and response, and also with an individual’s physical functioning and quality of life. How all these aspects link together, and how cognitive behavior therapy may be used to break into this cycle, are described below.

Maria holds a belief that the world is a dangerous place. She also believes that, if her awful predictions come true, she will not be able to cope on her own. Maria constantly encounters events that generate unhelpful automatic thoughts about danger or not being able to cope. These lead to repeated experiences of intense anxiety. This begins to affect Maria’s psychological and social functioning. She starts taking time off work, which leads to negative thoughts such as “I’m a coward” and “I’m useless.” This promotes feelings of sadness and depression. As well as being unable to get to her workplace, Maria is no longer able to attend social gatherings. Unfortunately, she eventually becomes unemployed and loses contact with friends. This has a number of associated problems, not least financial difficulties and social isolation. These conditions cause Maria even more stress (through exposure to additional negative experiences and situations) and distress (negative reactions to these difficulties), leading to loss of sleep, and other physical symptoms associated with low mood (e.g. not eating). These symptoms in turn lead to Maria feeling more depressed.

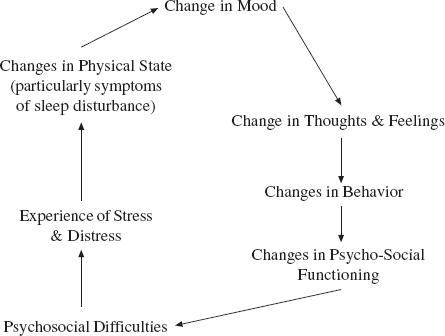

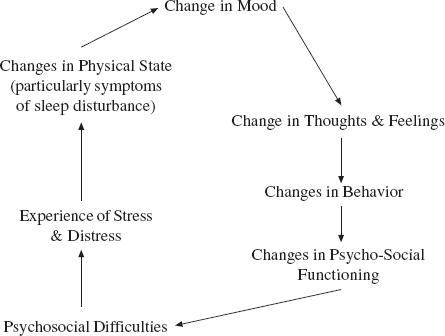

You can see from this example how the cognitive behavioral cycle influenced all aspects of Maria’s life. The starting point was activation of her underlying beliefs. In individuals who also have a biological vulnerability to develop a mood disorder, the cycle could also start with a disruption in circadian rhythms or a change in their physical and emotional state. No matter what the starting point, once the cycle begins, the changes and difficulties that occur are similar for each individual. Mood shifts in turn lead to changes in how that person thinks, feels (worsening depressed mood, or depression compounded by anxiety or irritability, etc.), behaves, and functions. This pervasive effect on a person’s functioning and quality of life is demonstrated in Figure 4. Another example is given below for you to follow using the diagram.

Figure 4 The cognitive behavioral cycle

Duncan was a 42-year-old businessman. His business was struggling financially (stress). Duncan was worrying about this and was not sleeping (physical symptom). However, with this reduction in sleep he noticed he was feeling rather better in his mood (mood change); he became optimistic that he could solve the problems of the company by increasing the cashflow through a few “quick deals” and some “creative thinking”. He thought he was “a genius”: he had a plan to use some money to invest in a mink farm (changes in thoughts and behavior), and would cover this venture by “generating” some additional resources from his family income. He would use his own salary to place bets at the local casino. Duncan became increasingly preoccupied with these schemes and spent less and less time at home. His wife was frustrated that he was not around much, and that when he was, he seemed “distracted” (change in psychosocial functioning). He decided not to tell his wife about the casino as he thought she would “worry too much” and “be a wet blanket”. The mink farm scheme failed, and Duncan lost increasing amounts of money at the casino. His mood shifted from elation to irritability, and one of his employees took out a complaint against him because he had been rude and angry with her during a meeting. His problems were compounded when his wife confronted him with the household bank statement: they had a large overdraft and the bank manager wished to see them (psychosocial difficulties). As the tensions at work and at home continued and the financial problems of his company and his personal overdraft got worse, Duncan began to feel tense, worried and depressed (stress and distress).

You may now wish to see if you can apply this model to your own recent experience of mood swings, both the ups and the downs. To help you, additional blank copies of this diagram are included in the Appendix (p. 224 and 225).

CBT aims to teach individuals to intervene at key points in the cognitive behavioral cycle. It encourages individuals to cope with mood swings by helping them to:

• understand their biological and psychological vulnerability factors, particularly their own underlying beliefs, and how these influence their well-being;

• identify and understand the nature of stress, particularly events that activate underlying maladaptive beliefs or events that disrupt their social patterns (social rhythm disrupting events);

• use self-regulation to reduce distress (such as the early symptoms of a mood swing), stabilize their mood, and reduce high-risk activities such as excessive use of alcohol or illicit drugs, or irregular adherence to medication;

• use self-management strategies to overcome intense mood swings by altering their active responses and identifying and modifying unhelpful automatic thoughts;

• develop an action plan to deal with early warning signs and symptoms, so that they have a greater chance of averting an episode of mood disorder;

• develop problem-solving skills that can be applied to a number of issues, such as overcoming the negative consequences of a “high”, and improve their day-to-day functioning and quality of life.

Reading this description may lead you to think there is too much to do, which in turn may make you feel anxious. However, there are a number of issues to bear in mind. First, remember that CBT is a step-by-step approach, so you only need to look at one issue at a time. Second, CBT is a flexible approach: not everyone reading this book will want or need to achieve all the aims on the list. Third, the advantage of using this book is that, if you choose, you might use it for a while, then have some breathing space before tackling other issues. Fourth, and very importantly, CBT recognizes that everyone is different and that you will need to decide which of these aims concern you most. Finally, you will be in the best position to judge which approaches work best for you.

To help you think through your own needs, you may like to look back at the list of aims above and identify those that are really important to you and which you may want to work on. Again, it is really helpful to write down your list of priorities.

The next three parts of this book examine some of the cognitive and behavioral techniques that you may use to tackle some of your problems. Most of these techniques are also used in a course of CBT when a therapist and client work together. Some of you reading this book will find working alone easier than others. Practice and regular revision of the techniques described undoubtedly helps. It is a good idea to review the aims of each part of the book and then to read through each section a few times, perhaps making notes on the key points. Try to be clear in your own mind what each technique is about before testing it out in practice. Remember, there will be an element of trial and error, so it is useful to look on each attempt as an experiment. If something doesn’t work out as you hoped, try to review exactly what happened, and what you can learn from this. Could you adapt the technique to increase the chances of the “experiment” succeeding next time? This approach is more productive than simply giving up and thinking the techniques won’t help you.

Even with supreme effort you may struggle to use every technique effectively. Please do not be hard on yourself if you find some things difficult. This does not imply that you are less able than other individuals, or that you have failed. Not all techniques are equally helpful for all individuals. Some people may simply find it hard to keep going on their own, and may decide to seek professional support. Again, this is entirely appropriate. There is no rule that says a person has to solve all of their problems by themselves. This may be particularly true if you have a long history of mood disorder, if you have very intense swings, or if your problems have proved difficult to handle in the past.

Lastly, this book does not to try to cover every aspect of every problem that every individual with a mood disorder has ever experienced. Some issues have been omitted because I did not think we could deal with them in a self-help book. The obvious example of this is the management of psychotic symptoms, as individuals with these invariably need more intensive support and treatment. Other issues have been left out because of the constraints of space, or because of my own ignorance. I anticipated that you would not want to plough through a book of 2,000 pages, so you will appreciate my decision regarding the former. On the latter point, I can only emphasize that this is still a relatively new area of clinical and research work, and I still have many things to learn about mood disorders and their management. With this in mind, you may wish to complete the feedback questionnaire at the back of this book to help me and my colleagues learn from your experiences of using this self-help programme.

Summary

• The term “cognitive” is applied to automatic thoughts and underlying beliefs:

– automatic thoughts are situation-specific;

– underlying beliefs are silent rules we apply across many similar situations.

• The cognitive behavioral model of mood disorders suggests that:

– An individual’s emotional response to an event is dictated by their automatic thoughts about that situation.

– The content of the thoughts is determined by a person’s beliefs about themselves and their world. Unhelpful automatic thoughts demonstrate common patterns of cognitive distortion.

– Underlying beliefs develop from early learning experiences. Maladaptive beliefs operate like prejudices we hold against ourselves.

• Situations that activate maladaptive beliefs generate unhelpful automatic thoughts that in turn affect an individual’s emotional and active responses.

• These responses may precipitate further difficulties in how a person functions, leading to psychosocial problems, stress, and distress. The end point may be changes in physical state as well as further emotional disturbances.

• The cognitive behavioral cycle can be precipitated by:

– activation of underlying beliefs;

– circadian rhythm disruption or other physical changes that lead to sleep disturbance.

Once the cycle is established, all aspects of an individual’s life are affected.

• Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) aims to help people identify and manage the causes and consequences of the cognitive behavioral cycle of mood disorder.

• Not everyone will find the techniques described in this book easy to use or helpful.