When an individual experiences a “high”, their mood change is often compounded by difficulties in recognizing that their actions are extreme and outside of normal boundaries. Also, they are easily distracted and unable to focus on the task in hand. This means that it is important to try to keep any self-management interventions simple. This chapter describes techniques to control unhelpful behaviors and basic strategies to modify unhelpful automatic thoughts. However, these techniques are most effective in the early stages of a high; it is unlikely they will be feasible if you are in the midst of a manic episode.

The main difficulty for individuals who are experiencing a high is that they have too much energy, and struggle to exercise full control over their own actions, which may involve a worrying level of risk-taking, or be open to misinterpretation by other people. This in turn may lead to the individual becoming irritable with people who prevent them going ahead with what they want to do. The key unhelpful tendencies are:

• distractability – inability to complete tasks;

• risk-taking – engaging in ill-judged activities through overestimating the gains and/or underestimating the dangers;

• impulsivity – acting without thinking things through, often associated with disinhibition;

• irritability – common in dysphoric mania, but also present in euphoric mania when actions are thwarted by others.

There are a number of strategies that can be tried to help reduce the adverse effects of these behaviors, but it is very difficult to use any of these techniques during a manic episode. It is therefore important to try to intervene as soon as the warning signs of a high are present, or at the latest during the hypomanic phase. The two basic approaches involve:

• keeping safe;

• maximizing self-control.

If you do not feel able to control all of your actions or totally trust your judgment, it is worth reducing your exposure to “risky” situations. Preparing plans when you are in a normal mood state that can be used when you are high is invaluable, as it is often difficult to put these approaches in place during a high without the help of others. Useful interventions include the following:

Keeping schedules simple and predictable Make a very basic, manageable and regular activity schedule. Even if you are full of energy, it is better to reduce rather than increase your planned activities from their normal level. Allow time between one activity and the next, as you are likely to find it difficult to retain your focus on each task. Don’t skip eating or sleeping. Indeed, make a particular effort to include regular meals, and regular times for going to bed and for getting up. Aim to spend at least 50 per cent of your daily schedule in a calm environment or engaging in relaxing activities. Try to avoid two areas:

• Complex tasks or problems: Keep your goals simple and delay any major obligations. If you do need to undertake simple tasks, try to persist with the activity until it is complete. Remember that when going high you are more easily distracted and at risk of starting lots of activities and finishing none. Push yourself to stay with each task before moving on to other things, no matter how attractive other activities may be. (This is the opposite advice to that for depression, where we used time limits.) If there are complex tasks that cannot be delayed, do not start them without recording a step-by-step approach and preferably enlisting the support of someone else.

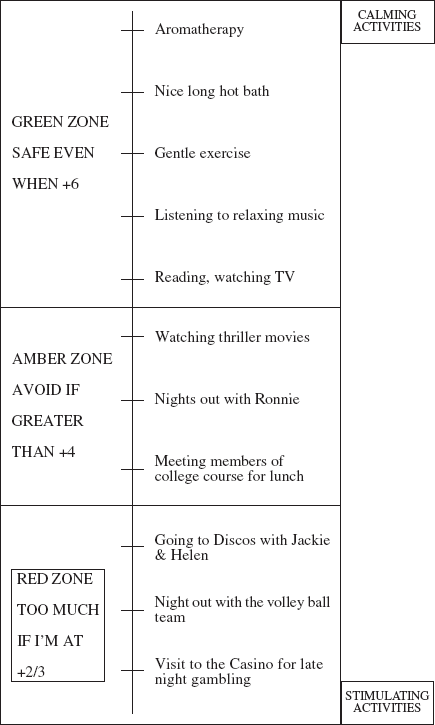

• Stimulants and stimulating people: Try to avoid situations, substances or people that push you even higher. One of my clients designed a “VROOMOMETER”, a chart listing activities that she was able to cope with at different stages in an upswing. She drew it up when she was in normal mood, and found it invaluable in picking out activities that were safe when she was in the early and later stages of a high. An example of such a chart is given in Figure 11.

Having made your plan, try to stick with it. Even if you feel full of energy, don’t try to add more into your day. The risk of inappropriate actions or problems is high and is better avoided. If when you review your day you do not feel you are using up enough of your energy, can you burn off some energy through exercise in a safe environment – for example, by swimming several lengths of a swimming pool? However, you must feel confident you can cope with that environment. If not, can you use an exercise bike or follow an exercise video in the confines of your own home? Try not to set endurance tests for exercise. It is better to attempt about half an hour per day and then review your schedule after four or five days to decide if any more exercise is likely to help calm you down and reduce your excess energy.

Calming activities As well as avoiding activities that are stimulating, it is important actively to calm yourself. This is achieved by ensuring that you incorporate relaxation sessions into your day, and also introduce other methods to reduce your level of arousal. For example, stay in familiar surroundings. You could even use a particular room in your home where you feel comfortable to take time out. Here you could lower the lighting or even sit in the dark for about an hour. Listening to relaxing music may help. Also, try to avoid exciting books or films if possible. A boring book is a good idea, particularly at bedtime! Slowly repeating simple phrases to yourself such as “relax”, “calm down”, or “take your time” may also work.

Figure 11 An Example of a “Vroomometer”

Safe thrills If you do not seem to be able to resist seeking out excitement, try to identify safe pleasurable activities. For example, rather than taking flying lessons, can you get access to a computer that has a flight simulator program on it? Rather than driving your car at speed, can you watch a video of a grand prix? These alternatives may seem less appealing, but it is important to remind yourself that the consequences are much less dangerous. If you feel compelled even to try these safer alternatives, limit your exposure to a maximum of about half an hour per day and preferably engage in calming activities immediately afterwards. Ideally, you should avoid even safe thrills if you are becoming manic, as the additional stimulation may have adverse rather than beneficial effects.

Managing social situations As emphasized earlier, it is wise to avoid some social interactions, particularly those that involve large gatherings of people. If you do engage in social interactions, try to space these activities out over the course of the week, and where possible keep the rest of your schedule regular and predictable. In any social interaction it is worth doing the following:

• If possible, sit down on a chair before you start talking.

• Sit upright and try to control your breathing.

• Work hard at listening to the other person’s comments.

• Don’t interrupt, no matter how keen you feel to join in.

• Wait for a gap in the conversation before speaking.

• Pause before you begin talking.

• Speak at a rate that seems slow to you.

• Do not use your hands as you talk – if necessary, try sitting on them!

Although you may feel very slowed down by this approach, it usually only just brings your activity and speech rate within normal bounds. If you are concerned that you have overcompensated and have slowed down too much, check this out with someone you trust.

If you are going high, you may be full of ideas and bursting with things you want to do. As a consequence, you can get frustrated and angry with people who fail to see the apparent brilliance of your plans or who try to stop you carrying out your planned actions. One way to reduce the risk of becoming angry is to try to increase your own control over your actions. The simple rule is: “Control what you can control, and don’t engage in behaviors that you can’t control.” If you are unsure whether you can retain control it is better to delay things than risk problems. To overcome your desire to act, you may wish to try the following ideas.

Record your idea or plan You may be convinced that all the ideas you have are good ones and should be implemented. However, it is worth trying to contain your impulsiveness. The apparent brilliance of your ideas is not always a reflection of reality. Individuals who are going high tend to notice only the strengths of an idea and are not always able to focus on the weaknesses. To help you avoid getting into battles or risky situations, keep a notebook to hand where you can record your ideas. You can then return to evaluate these ideas after you have recovered from your high. It will also be easier to convince others of your good idea if you present your plan after you are back to your usual self. If you follow this approach you actually have a greater chance of getting genuinely good ideas adopted, as they will not get lost in the mass of less viable proposals. You will also maintain your credibility as someone who does have moments of inspiration, rather than gain a reputation as someone full of erratic ideas.

Ban major decisions Maximizing self-control primarily involves restraining yourself from doing anything that you may regret later. It is vital that you do not make any major decisions about your personal or professional situation. Not everyone you meet will know that you are not your normal self, and some may take your decisions at face value. It is important to avoid decisions that have major consequences for your future, such as beginning new relationships or changing jobs. Any important decisions that you wish to contemplate should be listed in your notebook for future consideration.

This approach means that no one is taking decisions away from you or denying you the opportunity to lead your own life. You are retaining control by taking the initiative and choosing to delay any irreversible decisions.

48-hour delay rule Professor Aaron Beck, the father of cognitive therapy, has developed many of the approaches used to help individuals with bipolar disorders. One of the important techniques he describes is the “48-hour delay rule”. He states that “If it’s a good idea today, it will still be a good idea tomorrow and a good idea the next day.” This is a useful approach to many situations, but can be particularly useful in avoiding impulsive purchases, especially of very expensive items that you would not normally consider buying. During the 48 hours you have the opportunity to reflect on your plans and most importantly to seek advice from others on the wisdom of your proposed course of action.

An additional way to prevent financial extravagance is to surrender control of your credit cards to a trusted friend, or even to have an arrangement with your bank or financial adviser. Again, look at this as your attempt to take maximum possible responsibility for your actions, no matter what your state of mind. Getting help to prevent overspending will enable you to avoid some of the desperate financial problems that many other individuals have had to cope with after recovering from a high.

Third-party advice Individuals who are high find it very frustrating to have people criticize any proposals they make, and dismiss negative feedback as jealousy or lack of imagination. To overcome this, it is useful to identify in advance (i.e. when you are in a normal mood state) at least two people whose opinions you respect and whom you trust. You can then arrange to turn to these individuals when you are high to seek feedback on your ideas and planned actions. Having at least two people available offers a safety net in case you cannot contact one of them at the vital moment. If possible, you may even arrange that they regularly initiate contact when you are high and ask you to report any ideas you are considering acting on. They may be able to talk you through the pros and cons of your ideas, or help you record them. They can encourage you to return to these ideas when you are back to your usual self.

Being high is usually associated with positive but unrealistic automatic thoughts about your abilities and prospects for future success. Classically, individuals have an overoptimistic view of their world, in which they:

• overestimate the gains and underestimate the risks associated with any ideas;

• are totally focused on their own wants and needs;

• fail to attend to any negative consequences of their actions for themselves or others;

• experience angry thoughts as a consequence of their reduced tolerance of frustration.

Individuals who experience dysphoric mania also report negative automatic thoughts and irritability. (If this applies to you, you may find it helpful to use the approaches to unhelpful thoughts described in Chapter 9 on dealing with depression.) Techniques for modifying the automatic thoughts that accompany a high are outlined below.

If you are finding it hard to contain your wish to act on an idea, can you try to distract yourself from this course of action by thinking about other topics or by blocking the thoughts? Selecting another focus for your attention is helpful provided you do not simply move on to the next “big idea” that you have. Likewise, simply letting the first thought melt away is unlikely to resolve the situation, because your mind is working overtime and generating lots of new ideas. The critical element is therefore to distract yourself actively and to find a strong focus for your thinking that leaves no room for drifting back to your first automatic thought. Some individuals have particular images that they use; these may be relaxing scenes, or sometimes visions of the bad outcomes that have occurred in the past. You will need to try this technique a few times to establish whether it works for you.

Another approach is “self-talk”. Try repeating statements such as “I can resist this urge,” “I don’t have to act on this now,” or simply “Stop, it’s dangerous.” Keep the statements simple and repeat them as often as you can until you feel more in control.

If you are overactive and easily distracted, it is often too difficult to undertake a careful review of your automatic thought using the techniques described for depression. At best you may be able to push yourself to reflect on your ideas and to write down the pros and cons of any thought. However, it is important that the lists you compose bring in the information that is outside of your immediate focus of attention.

For example, when you feel high, you will tend only to see things from your point of view, or to see the enormous potential of the idea or the benefits of the scheme you propose. The critical aspect of the “two-column” technique is to ensure that you pay attention to the alternative. Namely, for each positive statement you write down, you should immediately respond with a statement on the downside of your idea. To help with this approach, ask yourself the following questions:

• What harm might this idea do to others?

• What is the destructive potential of the scheme?

• What are the potential losses?

You will have to work hard to come up with answers, and if this proves difficult you may wish to consult others to help you in completing this task. For example, can you call on the individuals you have nominated for third-party advice (see above)?

Table 5 gives an example of the “two-column” technique. Some blank copies of this form are included in the Appendix for your own use (pp. 238–40).

A common accompaniment of a high is increased irritability. If this is not tempered it may spill over into anger. Given that you may also be less inhibited than usual, the whole situation may become dangerous. Prevention is obviously important, but you are only likely to be able to take full responsibility for your anger and irritability in the early stages of a high. Later, you are unlikely to be able to control your emotions and actions without professional support and recourse to medication.

Step one in averting difficulties is to keep a list of situations that you know “wind you up” or frustrate you even when you are symptom-free. Ideally, arrange to stay away from the situations or people involved until you feel more settled and able to cope. If you find yourself in situations where you are becoming irritable and cannot immediately withdraw, there are two approaches you can try:

• engage in one or more relaxation or calming techniques;

• try to employ the social interaction skills discussed earlier in this section, particularly sitting down to talk, and speaking calmly and slowly.

Most irritability and anger can be traced back to your automatic thoughts. Thoughts that contain “should” statements are particularly powerful: “She should not talk to me like that,” “He shouldn’t try to stop me,” or “I should be allowed to do what I want.” While you may not be able to follow a systematic process of exploring these thoughts in the heat of the moment, you can still try to reframe them in less emotive terms. For example, every time a “should” statement goes through your mind, can you reframe it as “ I would prefer it if . . . ”? This does not change the fact that you have a negative thought, but it may help reduce the intensity of your reaction, and make the thought and your emotions more manageable. You could also try reminding yourself of the disadvantages or potentially negative consequences for you of acting upon your negative thought.

If you are still reasonably in control of your high, you may be able to review and modify your thinking as described in Chapter 9 on depression. Begin by noting the event or situation in which your negative thoughts arose, and the intensity of your emotional response. You may well find that many automatic thoughts that are associated with anger or irritability arise after someone has made a comment that you perceive as critical of you. Anger and irritability are often secondary emotions, arising in situations where your first response is that you feel hurt or upset. The good news is that you can stem your descent into irritability or anger if you can identify and challenge your initial negative automatic thought and deal with any hurt you are feeling.

Hidden behind the bravado that accompanies a high there may well be a fragile self-esteem that is easily wounded. Furthermore, many individuals report that as they come down from a high they feel quite depressed. This is an important time to be vigilant about comments you view as critical. You need to explore the evidence and examine the alternatives. Next, can you assess how accurate the comment is and also what would it mean if it were true? How could you change things if it were true? Finally, can you assess how sensitive you are being to other people’s comments? If you are being oversensitive, how can you manage your reactions differently?

Here is an example.

Steven was slightly high and feeling sociable, so he went into the canteen at work and sat down with some colleagues who were already chatting to each other. Steven was mildly disinhibited and began talking across the ongoing conversation. One of his colleagues said, “Please don’t interrupt just yet, Steven.” Steven felt angry as he wanted to tell them about some interesting ideas he had. However, before telling the colleague what he thought of her, he decided to try to review the situation and work out why he felt angry.

• Situation: With colleagues; asked not to interrupt.

• Angry thoughts: “She shouldn’t talk to me like that. She made me look foolish.”

• Initial automatic thought: “Maybe she doesn’t like me. They don’t want me to join them.”

• Initial reaction: Anxiety, hurt.

• Steven’s response: She actually smiled when she said “Please don’t interrupt,” and she did say “just yet”. The person they were listening to was just delivering the punchline of a joke.

• Steven’s decision: Try to stop mind-reading; also note I’m a little bit disinhibited and need to sit down before I speak.

Steven rated the perceived criticism as 40 per cent, but rated his perceived sensitivity as 75 per cent.

In writing about techniques for managing highs I have tried to pay attention to the fact that you are likely to be more distractible and disinhibited than normal. I realize you will struggle to implement some of these approaches. This chapter has therefore concentrated on simple techniques, rather than complicated sequences of interventions. However, even simple techniques will be hard to use when you are going high, and will be virtually impossible once you are in the midst of a manic episode. So, the more you try out these skills when you are your normal self, the greater your chance of being able to use them effectively when you are going high. As with depression, the role of other approaches such as self-medication and professional support are considered in the next chapter, on relapse prevention.

Summary

• Self-management of highs includes: understanding unhelpful behaviors such as:

– distractibility;

– risk-taking;

– impulsivity and disinhibition;

– low tolerance of frustration.

• Using key behavioral interventions such as:

– keeping safe;

– maximizing self-control: controlling what you can control; delaying or avoiding what you can’t control.

• Indentifying automatic thoughs particularly those focused on:

– overestimation of gains, underestimation of losses; – overoptimistic predictions;

– excessive focus on the self.

These thoughts are associated with feeling elated, but also with irritable mood.

• Using key cognitive strategies such as:

– active distraction;

– modification of unhelpful thoughts using the two-column technique; modification of “should” statements by reframing.

• These techniques are best implemented in the early stages of a high, as they are unlikely to prove feasible during a manic episode.