It all started when Sydney climbed out of the truck. Somehow, even though I didn’t know it yet, what happened that autumn morning is what set everything else in motion. The second the passenger door banged shut, I turned to my dad.

It all started when Sydney climbed out of the truck. Somehow, even though I didn’t know it yet, what happened that autumn morning is what set everything else in motion. The second the passenger door banged shut, I turned to my dad.

“So tell me, is she living with us now or what?”

My dad kept us idling at the curb while she promenaded all the way to the bus stop, finally turning to blow him a kiss. “No, not at all,” he said, snapping out of his trance. “She’s just going through some roommate problems. It’s not permanent.”

Until August or so, my little brother George and I had hardly ever run into Sydney, my dad’s girlfriend, even though they’d been seeing each other since the spring. Unfortunately, over the last month we’d started seeing a lot more of her.

Which, for me, was a real problem.

As we pulled away from the curb I snuck one last look in her direction. I tried to will myself not to, but I couldn’t help it. Today, an early October morning as warm and humid as summer, she was wearing a halter top and a pair of tight cutoff jeans.

Dad was obviously going through some kind of midlife crisis.

At twenty-six, Sydney was sixteen years younger than he was. I sometimes even caught myself staring at her, which wasn’t something I was proud of. I felt terrible about it, horrible. After all, this was my dad’s girlfriend.

I hated myself.

My eyes followed her across the window until she slipped out of sight.

“You could’ve fooled me. She spends more time at our place than I do.” I immediately regretted saying it. My dad wasn’t about to let a comment like that go, and I had other worries at that moment. Not only had we wasted time dropping off Sydney, but before that we’d taken too long getting George to school, and before that we’d left our house late because Sydney took forever in the bathroom. So now I’d already missed homeroom and would probably arrive late for my social studies presentation. I was first on today’s list.

“That’s not true and you know it,” Dad said, racing us through a yellow light.

I didn’t answer. When he glanced over at me, I couldn’t help thinking about how everybody was always saying how much we looked alike. And it was true that we had similar faces, both of us blond with glasses. My hair fell almost to my eyes, though, while his was cropped short and starting to go gray over the ears. Our glasses were very different too. I wore black rectangular frames while he’d recently bought round wire-rims like John Lennon. Sydney’s idea.

“Come on,” he said. “Out with it.”

I fiddled with the latch on my trumpet case. That afternoon I had freshman tryouts for Marching Band. “Well, for starters,” I said, “she’s a deadbeat. Practically every day I come home and she’s loafing on our sofa watching our TV. Either that or she’s helping herself to our food while she’s parked at our kitchen table doing her little drawings.” Sydney was studying part-time to be a graphic artist.

“She pulls her weight,” he said, as if that had anything to do with it. “She cooks sometimes, and picks up around the house. Unlike somebody else I could name.”

Right. She was like having our own nanny, the Nanny from Planet Mooch.

We shot past the line of orange cones in front of the school’s new, state-of-the-art gymnasium, a construction project that was supposed to be finished over the summer but was still not quite complete because of money problems. Finally, my dad’s truck screeched to a halt at the front entrance. That’s when he turned to me and gave his I’m-opening-up-to-you-so-cut-me-some-slack look.

“Look, I know you’re not sold on Sydney yet, but I happen to think she’s terrific. She’s smart and caring and a lot of fun. All I’m asking is that you hold your judgment, okay? Think about it? For your old man?”

I grabbed my backpack, my trumpet and the big manila envelope that held my presentation. I shoved the door open and hopped out of the truck.

“Okay?”

I slammed the door and dashed up the steps. Once inside the school building, I knew from the empty hallway that the first-period bell had already rung.

I sprinted down the long central corridor. Up ahead I happened to pass Jonathan Meuse as he jogged toward one of the chemistry labs. A popular junior with a lot of friends, Jonathan was tall, redheaded and about as clean-cut as they came. He looked like a soap commercial with biceps. Most significantly, he was the student leader of the Marching Band trumpet section and would be at the tryouts that afternoon. I often ran into him in the hallways but he never acknowledged my existence because I was only a freshman. Like now. I’m positive he saw me wave but he ignored me.

I kept running.

Unfortunately, seeing Jonathan brought my mind back to this afternoon’s tryouts again, which sent another jolt through my stomach. There was a lot on the line today. The way I saw it, getting into the high school Marching Band would be vital for my social life. I know, I know. You’re probably thinking I’m nuts, that Marching Band kids are usually the opposite of popular. But I’d been studying it, and it was clear to me that Marching Band nerddom wasn’t a firm rule. Just look at Jonathan—he’d figured out how to use it as a springboard to cool. And so would I.

Thing was, after two long years of living in middle school Nobodyland, I’d spent the beginning of ninth grade secretly observing the most popular kids—not just Jonathan, but also Seth Levine, Scott Pickett and guys like that—to see if I could learn anything that might improve my own social status. I figured if I emulated the coolest, after a while everybody would assume I was cool too. Like, right then I was wearing the same kind of Polo shirt and khaki pants I’d once seen on Seth Levine. When I’d waved to Jonathan, I did it in the same way I’d seen Scott Pickett wave to his friends—one motion, like a windshield wiper that suddenly stops midway. Yeah, I know this probably sounds stupid, but that was my strategy. If it looks like a duck and quacks likes a duck, it’s a duck, right? It was all about attitude. Anyway, one other thing I’d noticed in my research was that pretty much all the popular guys were in at least one club or another. Usually it was sports, but not always.

Of course, sports were out of the question for me since I was about as coordinated as a jellyfish.

Which left me with Marching Band.

It might not be the football team, but it was all I had.

Finally I reached my classroom. By the time I burst through the door I was out of breath. Mr. Prichard, a stocky rooster of a guy, glanced significantly at the clock. “Well, well, well, Wendel. We were beginning to wonder if you were going to make it.”

“Sorry I’m late,” I panted, stepping past him and to my seat.

“We’re just pleased that you deigned to grace us with your presence at all this morning.”

I set my bag down.

“You do recall that today you’re presenting, correct?”

“Uh, yes. I’m ready to do it now, if you are.” I tried to grin confidently but was so frazzled that I think all I managed to communicate was panic.

“That would be nice.”

Drew Baker and Jesse Rathbone, a couple of jokers I knew from middle school, leered at me.

I grabbed the envelope and headed to the front of the room. On the way I took a deep breath and told myself to calm down. I was prepared for this. I knew everything about Bolivia. I’d memorized a speech about the Altiplano and the Yungas, I’d printed two five-color maps showing rainfall patterns and population density, and I’d even made handouts demonstrating the catastrophic effect the drought caused by El Niño in 1997 and 1998 had on the potato harvest. This would be a cinch.

But as I pulled the stack of papers from the envelope, my heart nearly stopped.

The top sheet was not one of my handouts. It was a charcoal sketch of a solemn-faced woman lying on a sofa. A completely naked, solemn-faced woman.

“Wendel?” asked Mr. Prichard. “Is there something wrong?”

I flipped to the next sheet. The same woman leaning forward with a pencil in her hand. In the one after that she sat on the floor. I was holding an entire stack of nude drawings of some lady.

Olivia Whitehead, a large, silent girl with shapeless hair that hung in a flat sheet around her head and often looked like it could use a good wash, gaped at me from the front row, her mouth hanging slightly open. I could hear her breathing.

I felt myself starting to sweat. How had this happened? Then I remembered Sydney asking my dad for an envelope to carry her most recent sketches to class. It was a drawing seminar called The Human Form. My dad had given her an identical envelope from the same stack as mine. Sitting next to me in the truck, she could easily have grabbed my envelope by mistake and left me hers.

That’s when I looked more closely at the woman’s face. It wasn’t perfect, but she had the high, wide cheekbones, the tumble of unruly hair and far-apart eyes like a bird’s. A wave of horror washed over me. It was Sydney. She must have sat in front of a mirror and used herself as a model.

Staring down at Sydney’s body, I suddenly realized that (a) there was no way I would be able to do my presentation, and (b) I was standing in front of my entire social studies class holding a stack of naked self-portraits of my father’s girlfriend.

Once upon a time there were five little darlings named Charlie, Olivia, Wen, Mo and Stella, who sprang from the earth in a flash of light. For a while they stood around, ignoring each other and wondering who had put them together and why. All of a sudden a Kindly Old Fairy Godlady appeared before them and waved her wand saying, quote, “Thou shalt sprout Mouths of Lemonade!” And so they did, and, fortunately, they soon discovered that it was neither as sticky nor as uncomfortable as it had at first sounded. “Thank you, Kindly Old Fairy Godlady,” they said, thanking her.

Once upon a time there were five little darlings named Charlie, Olivia, Wen, Mo and Stella, who sprang from the earth in a flash of light. For a while they stood around, ignoring each other and wondering who had put them together and why. All of a sudden a Kindly Old Fairy Godlady appeared before them and waved her wand saying, quote, “Thou shalt sprout Mouths of Lemonade!” And so they did, and, fortunately, they soon discovered that it was neither as sticky nor as uncomfortable as it had at first sounded. “Thank you, Kindly Old Fairy Godlady,” they said, thanking her.

What can I tell you about Sista Stella that you haven’t by now heard from those who already think they know everything?

Plenty.

I wear boxers. I like fruitcake. I’ve been a vegetarian since eighth grade. The summer after that, my mother got a new job heading a start-up development project at a lab in Rhode Island (something to do with saving the planet by making cheap biodegradable plastic out of plants), so a week before high school began, my family (my mom, my sister, Clea, and me, plus Leonard and the step-monkeys) had to pack our bags and load a U-Haul. If we hadn’t left Tempe, Arizona, would there still have been Lemonade Mouth? Who’s to say?

If you want the story of my part in everything—and you want it to make sense—then I can’t jump right into Lemonade Mouth. I’ll need to begin a little earlier, explain a few things about my screwed-up life. There are a lot of misconceptions out there.

Let’s start with my hair. As a lot of people know, since I was a little girl I’d always kept it all the way down to my waist. So why, two weeks into my freshman year, did I, in a fit of frustrated rage, hack it all off, leaving little more than short tufts?

Allow me to carry you back in time to that fateful Monday in late September when Stella, our incorrigible heroine, locked herself in the bathroom and went to work with a pair of scissors.

What on earth could have possessed her? What was going on in her head? At the time there were a number of theories.

My own mother, for instance, days later (after she’d gotten over her initial shock at seeing her formerly long-haired offspring in this new and strange state), would give a patronizing roll of her eyes and explain to anybody who asked that “Stella’s still working through anger issues about moving.” Which of course I was. It wasn’t my idea to transplant my already sorry excuse for a life across the country to some nothing little town I’d never heard of. And did anybody act like I even mattered in the decision? Neither my mother nor Leonard had even asked for my thoughts before announcing that the move to Rhode Island was a done deal. Nobody ever asked my opinion. And after that, everything seemed to happen in a flash. Before I could even say quahog, I found myself in New England at a cliquey new school that I hated, where I didn’t know anyone and nobody talked to me.

“Thank you, O Mother Dear,” gushes our smiling young protagonist, “for uprooting me from everything I’d ever known and loved!”

Of course I was angry. Who wouldn’t have been?

Yes, the move may have been part of the reason why I ended up rifling through the kitchen drawers for a pair of scissors on that clear September evening. But it may surprise some of your readers to hear that it was not ultimately what pushed me over the edge.

My sister, Clea, who had recently started her freshman year at nearby Brown University but still often spent evenings stretched out on the family sofa in a self-absorbed fog, had a different theory. She thought it was all about a missed appointment.

“We all know Stella,” she was overheard snorting to Leonard the next day. “She’s immature and always has to have her own way. In her mind, just because she finally decides to get her hair styled, that means the whole world should stop in its tracks. So when my car breaks down and Mom has to pick me up instead of driving her into Seekonk for her all-important appointment, what’s her natural reaction? Tizzy overdrive!”

As with many wrong theories, this one also wasn’t completely devoid of truth. My mother had promised to drive me to get my hair cut, and in fact, this was the third appointment the distracted woman had made me cancel due to last-minute “emergencies.” And I was indeed desperate to fix my appearance. It probably sounds strange, but after the move I started obsessing about things. I felt self-conscious about how much I’d grown over the summer—I’d always been on the tall side, but now I stood just over six feet in my socks. And my superlong hair was suddenly all wrong. I was all wrong. It didn’t help matters that on my second day at my new school, as I ambled down the aisle to take my seat in Algebra, I passed a girl in a mohair cardigan and overheard her whisper, “Hippie Bigfoot,” to the girl beside her, another mohair cardigan. I nearly died. Clearly, some drastic change was required if I was going to fit in around here. And since there was nothing I could do about my height, I suddenly felt my ’do was the obvious place to start. Something shorter, with more style, more oomph. Even though it would be a sacrifice, I was determined to make it happen as soon as possible.

But it wasn’t my family’s constant crises that led me to the radical mutilation of my coiffure.

Some people say it was because of Mr. Brenigan, the Vice Principal at Opequonsett High School. They point out that the very day I got busy with the scissors happened to be the same one in which the high school Powers That Be sent me home for wearing an allegedly offensive article of clothing. All it had been was a plain army-green T-shirt, albeit snug-fitting, onto which I’d added half a dozen handprints in yellow acrylic paint. But the small-minded autocrats in the front office felt that the shirt was somehow inappropriate for a learning environment. The shirt was, of course, art. It was also the trademark look of Sista Slash, the famous activist and musical anarchist. I used to wear mine at my old school all the time, so when I picked it out that morning I honestly hadn’t thought anything of it. But Mr. Brenigan insisted that I could return to school only after I’d changed into more appropriate attire.

Even now I can remember his exact words:

“Opequonsett High doesn’t have a dress code, exactly. It’s just that we have an unwritten line and that shirt crosses it.” Mr. Brenigan, who looks like a tired Michelin Man with a receding hairline, leaned back in his chair and tapped his fingers together while he talked, as if what he was saying was deep.

“But … what about freedom of expression?” I asked, trying to hide the fact that I was nearly crapping in my jeans. It wasn’t as if I’d ever been sent home from school when I lived in Tempe. Juvenile delinquency was new to me.

Mr. Brenigan gave me a steady gaze that went on and on. I began to wonder with growing alarm whether I’d missed something. That’s another thing you ought to understand about me—I often found myself struggling to keep up, and it freaked me out a little. Maybe because every other member of my family was certifiably brilliant. My father, a biochemistry PhD like my mother, was working on a cure for pancreatic cancer in St. Louis. My sister was at Brown. My mother ran a lab that sounded like something straight out of science fiction, for godsakes! Even my stepfamily was impressive. Leonard had started his own software company and was a millionaire by age twenty-five, and the step-monkeys, at eight, were already demonstrating a surprising aptitude for taking apart their electronic toys and putting them back together again. My own apparent dumbness was a source of constant embarrassment. In biology class on my very first day, for example, instead of paying attention to Mrs. Birch’s long, boring speech about some moth in England, I’d found myself staring at Mrs. Birch’s belly, which stuck out from her otherwise-slender body like a beach ball. At the end of the lecture, when the teacher asked if anybody had questions, I raised my hand and asked, “Are you pregnant?” At this, the boy next to me quipped, “No, Einstein, she just stuck a pillow under her shirt. It’s the latest fashion.” The class broke out in fits of laughter. I tried to shrink in my chair.

Anyway, during Mr. Brenigan’s long silence I felt myself blush.

Eventually he half smiled. “You can’t change the world. We run a tight ship here, Stella, and everybody’s part of the same crew. I don’t know what you were used to back in Arizona”—at this point he eyed me significantly as if he were studying an obvious bad egg from a scandalous part of the country—“but you’ll soon learn that here, we respect the rules. Written and unwritten.”

As you might imagine, that almost sent me into a frustrated conniption. So it does seem plausible that the T-shirt incident, together with Mr. Brenigan’s speech, the memory of my stolen Arizona life, and the reality of finding myself an outcast in a new unfriendly school in a hostile new state, as well as my mother’s obvious disregard for my feelings might, in combination, have been enough to set off the whirlwind of snapping scissors and flying hair that soon followed.

But it wasn’t. Not quite.

Not to say that each of those points didn’t weigh on my troubled mind. They absolutely did. But what ultimately sent me storming into the bathroom that night was something else.

So what was it? All right. I’ll tell you.

The truth was, I didn’t really know. All I understood was that I’d had a feeling welling up inside me for a while, a feeling I’d barely noticed at first but that now was growing so fast it was practically taking over everything else. Like I was going to explode. Like all the atoms in my body were getting ready to burst and it was only a question of when.

I was a walking time bomb.

A piece of paper I received that day may also have contributed to The Hair Incident. In some other week, perhaps, the bad news delivered on this document might have rolled right off me instead of hitting me head-on like a renegade garbage truck. But given my volatile state in that monumentally crappy twenty-four-hour period, it’s possible that this little spark might have been all that was needed to set me off.

So what was it?

It arrived in the mail. At home that afternoon, waiting for my mother to drive me to my appointment (still unaware that said appointment wasn’t to be), I checked the mailbox. I noticed the envelope addressed to me right away—it was long and white and in the top left corner was the address of J. Edgar Hoover Middle School in Tempe, Arizona. There were several stickers eventually directing the letter to Rhode Island. I had a sudden idea what it was. Back in June, my old school had held a “Future Careers Fair” where a nurse, an insurance salesman, two artists and a veterinarian spoke to a crowd of eighth graders about their jobs. We could choose to take short written multiple-choice tests that were supposed to tell us about our personalities, aptitudes and the kinds of careers we might consider someday. Foolishly, I’d signed up and taken the tests. The results were apparently mailed late and, since my family had moved, had taken even more time to find their way to me. To be honest, by then I’d forgotten all about that fair.

But now here was the envelope. So I opened it.

Within seconds I felt like day-old crap.

Now, please forgive me if I don’t detail everything the letter said, except to say that it included an IQ score that confirmed my worst suspicions about myself. I knew something about IQ scores. My mother, a member of Mensa, the club for people with intelligence quotients in the top two percent of the general population, has an IQ of 164. I knew that 100 was average. So when I saw the number written by my name, that about-to-explode sensation I’d felt growing inside me for days quickly swelled until it was almost unbearable, until it literally throbbed through my body. Here was indisputable proof of why I so often found myself lost in class, why I was bad at math, bad at English, bad at everything.

Eighty-four.

In a family of geniuses, I was now a documented dummy.

I believe there are moments that can make you burst out of yourself, smash through the boundaries of your everyday life, the unhappy existence you have until then accepted without protest, and make a change that is dramatic, unexpected and right. And that, my friends, is the only explanation I can offer for what I did to my hair that night, why I apparently lost my mind.

Within minutes after my mother came home, I was at the bathroom sink with my hands gripping the porcelain so hard my knuckles were white. In the mirror my bangs covered my eyes, and shapeless turd-brown hair framed my grimacing face like limp drapes. Eighty-four! I wanted to scream but didn’t. Instead, I held the scissors just above my left cheek and made the first cut. A long ribbon of hair fell to the floor. After hacking off the length from first one side, then the other, I reached behind my neck and bunched the remaining length in my fist.

It was gone in one vicious chop.

I was burning so hot that I wasn’t thinking straight. I’d finally figured out why everybody else always seemed to make the decisions without asking me, why the universe was out of my control, run by the crappy ideas of other people. It was because I was stupid. I hated my life. And each slice of the scissors felt like a stab at my whole messed-up world.

Here’s what I thought of Mr. Brenigan. Yank-snip!

Here’s what I thought of natural selection and genetic variation. Yank-snip! Yank-snip!

It was only when I noticed the impressive piles of hair in the sink and on the floor that I came out of my trance. I balled my fists, each breath short and sharp. I blinked at the stranger who looked back at me from the mirror. My bangs were gone, and all that remained elsewhere on my head were short wisps that jutted out at harsh angles.

I’ll admit it: I felt a brief moment of panic. What had I done? How was I going to face my mother? How would I get through the next day at school?

But then something unexpected happened. I stared hard at my reflection, truly studied myself. I could actually make out the shape of my head for the first time in forever. I leaned in closer. I couldn’t remember having such a clear view of my ears. My neck either. It was thick and white and strong. I liked what I saw. Even my wide cheekbones, which I’d always thought made me look like a gorilla, now seemed almost regal.

And then, standing in the bathroom with most of my hair at my feet, I felt an unexpected adrenaline rush. The girl in the mirror was a different Stella that I barely recognized. Yet at the same time, she was like a long-lost friend, somebody I’d known all my life but didn’t see a lot of.

I was looking at Sista Stella, my alter ego, my evil soul-sister.

The girl glaring back at me didn’t need friends. She was a rock. She didn’t care about geniuses or about Mr. Brenigan, or Mrs. Birch, or planet-saving Frankenstein plants, or her cliquey high school, or anything. She wasn’t some frightened puppy, willing to sit down and obediently accept whatever crap the world dished out. She wasn’t about to let other people make any more decisions for her.

In fact, Sista Stella was about to make a few decisions of her own.

I have to be honest English Comp is not my favorite subject. Which must be obvious to you since here I am having to do this extra paper just to squeak by with a C. But I’m terrible at writing. It takes me forever to get my thoughts organized. And I’m never sure how to begin either.

I have to be honest English Comp is not my favorite subject. Which must be obvious to you since here I am having to do this extra paper just to squeak by with a C. But I’m terrible at writing. It takes me forever to get my thoughts organized. And I’m never sure how to begin either.

So I guess I’ll just keep typing.

The 1st part of my story is kind of embarrassing I don’t come off very well. In fact it kind of exposes the fact that I’m a big fat loser. You might even feel sorry for me. But I promise you it won’t last.

The very very beginning part is also a little complicated. And kind of weird too. So bear with me.

I was in study hall minding my own business listening to my headphones. My eyes were closed and I was drifting in and out to Tito Puente. Do you know Mambo Diablo? Anyway that was the tune that was lulling me into a dream where I was playing my timbales and Mo Banerjee was getting into the rhythm she was dancing and it was a really good dream except I kept getting distracted by the voice of my dead brother Aaron. Right then he was saying things like This is YOUR dream Charlie so why not make her dress shorter? or Get a grip! Stop playing your stupid drums and kiss her!

Sometimes Aaron can be a pain in the butt.

OK so to shut him up I gave her a very very short red dress and high heels that I know she’d never really wear in real life. Anyway my sticks kept whizzing through the air like my hands were on fire. Like my body was only there to support my arms, you know? The ecstatic crowd jumped to its feet. Mo kept moving her Hips and gyrating to the music. She was a good dancer in my opinion. Then the next thing I knew she danced right up close and I felt her dark eyes on mine and my heart started hammering because I suddenly realized she was about to kiss me but even so I just knew that Aaron was going to say something obnoxious and ruin it.

That’s when I felt the 1st spitball whack against my cheek.

I woke up with a lurch and yanked off my headphones. Gradually I remembered where I was. Mrs. Reznik the Music Teacher, a tiny scary old lady with a permanent cough, sat at a beat-up desk at the front of the room with her eyes closed like maybe she was having a dream too. The other kids sat quietly in their seats. Most of them were staring out the window looking bored out of their minds. Some of them were even doing homework. I touched my face. The wet wad of paper was dripping with someone else’s spit. It trickled toward my mouth. It was really REALLY gross. I scooped it off and rubbed my cheek on my sleeve. Yuck.

An instant later a 2nd spitball hit my left ear. Somebody stifled a laugh and when I turned to look, there were Scott Pickett and Ray Beech and Dean Eagler engrossed in their studies.

Yeah right Aaron said somewhere in my head. I wasn’t surprised he was still there. He’d been making occasional appearances in my thoughts for days. They’re not fooling anybody.

These guys were part of Mudslide Crush which as you know was a popular local rock band and everybody seemed to think they were the coolest kids ever to walk the hallways. They seemed convinced of it too. Ray especially enjoyed giving freshmen like me a hard time. He liked to call me Buffalo Boy. I guess because I have a lot of frizzy hair I keep kind of longish and I’m a little chubby. Not that Ray was exactly svelte. In fact he was a giant toad of a guy but that didn’t seem to matter. He had a name for everybody. Earlier that week I saw him knock Lyle Dwarkin into a wall. Lyle’s 14 but looks 10 and has to be the shortest kid in our grade. He was one of my few friends and he was ahead of me coming out of Metal Shop when Ray bumped into him and kept walking without even looking back. Like he didn’t even notice.

Ray was a real lowlife.

I wiped out my ear. I figured I had 2 options. On the 1 hand I could try for revenge on the other hand I could just ignore those guys. After all there were 3 of them plus I had a list of Irregular Verbs to review for 6th period Spanish and my Mother had been on my case about the 72 I got on the first quiz. It wasn’t fair for them to get away with being such jerks but what could I do? Everyone has to have their turns being freshmen I guess. Maybe if I studied quietly and didn’t make a big deal of the spitballs Ray and his friends would leave me alone.

It was definitely the safer plan.

Go for it Aaron whispered. Look at Scott’s wet fingers. It was him! Hurl a fat one right at his head!

Shut up I told him silently.

I want to stop right here and say that I’m not crazy in case that’s what you’re thinking. I knew perfectly well that Aaron’s voice was only in my imagination and that he was really long gone. But my 14th birthday was only the previous weekend and my Mom and Dad and I went to visit his grave. After that I started thinking about him and what life might’ve been like if he was still here. Or if I’d of been the one stillborn with the umbilical cord wrapped around my neck instead of Aaron. It’d just been the luck of the draw, right? And people do say twins share a special connection. I read one time about a guy that fell in a deep hole and his twin who was miles away started getting these weird vibes until eventually he went out and saved him so the way I figured, it wasn’t completely whacked for me to have these imaginary discussions with the brother I never knew.

Still, I know it’s not normal, is what I’m saying. No need to send me to the guidance counselor, Mr. Levesque. Or lock me in a padded room or something.

My eyes fell on a drawing somebody made on my desk. A circle with a curved line down the middle, 1 side filled in with pencil. Yin and yang. Of course. With my cheek still warm from the spitball here I was staring at the ultimate Symbol for no right answer. The struggle between opposing forces. Action and Inaction. Success and failure. There was an uncomfortable balance in the Universe and who was I to try and tip it?

I couldn’t make up my mind what to do so I pulled out a quarter and tossed it into the air. Heads I’d throw a spitball of my own, tails I wouldn’t. When the coin landed I was staring at George Washington.

Decision made.

I slid down my chair and quietly tore half a page from my spiral notebook. I wadded it up and popped it into my mouth. As I chewed, Ray whispered something to Scott and then Scott looked over at me and grinned. I dropped my eyes and pretended I was studying my list of Spanish conjugations.

Yo tiro. Tú tiras. El tira. Nosotros tiramos. Ellos tiran.

A moment later I held the spitball under the table and rolled it between my fingers. When I judged that the moment was right I wound my arm back. I focused on the skin between Scott’s ear and his annoying smirk. Then I let it fly. It whipped through the air and landed with a loud, soggy thwack!

That’s when Mo Banerjee who was sitting right in front of Scott stood up and screamed.

“Aaaaaaaa!” she wailed, swatting the wad off her face and glaring in my direction. “So gross who was that aaaaaa!”

I cursed George Washington and my terrible luck. How had I managed to completely miss Scott and instead hit Mo right on the nose? I sank deeper into my chair. I wanted to disappear. Scott looked from Mo to me and back again. Then he laughed and so did Ray and Dean.

Oh man. You screwed up big this time.

With a violent cough Mrs. Reznik suddenly seemed to wake up. “Who did that?”

Since Mo was still screaming I worried I actually might of hurt her. Maybe even broken her nose or something. Was that even possible with a spitball? Oh God. Maybe.

“Mr. Hirsh” Mrs. Reznik said with her eyes boring a hole right through me. “Did you throw something at Miss Banerjee tell me this instant!” I know I shouldn’t say this but Mrs. Reznik always kind of freaked me out. Especially because she was really REALLY old and had this outrageous swirl of stiff brown hair like a giant chocolate cake on her head. It was lots more hair than I thought was natural and I was pretty sure it must be a wig because it never moved and never changed from day to day.

I felt my face heat up. I nodded. I knew this meant detention at the very least.

Behind me Leslie Dern and Kate Bates snickered.

“What was it?”

“A spitball!” Mo shouted. Her chin was out and her eyes narrowed at me. “Charlie you are a pig!”

I slipped further into my chair.

For once Aaron kept his mouth shut.

“Need anything, Mo?” Mrs. Flynn asks from behind her computer screen. “Water?” From the way she’s looking at me it’s obvious she’s as surprised to see me in trouble as I am.

“Need anything, Mo?” Mrs. Flynn asks from behind her computer screen. “Water?” From the way she’s looking at me it’s obvious she’s as surprised to see me in trouble as I am.

I shake my head and stare at my knees.

It’s Thursday afternoon and I’m fighting back panic on the long bench in the front of Mr. Brenigan’s office, my double bass under my feet. I start to gnaw at one of my fingernails but then stop myself. I feel pressure building up behind my forehead—the first signs of a stress headache. I should’ve guessed this day would turn out to be a complete disaster. First I get whacked in the face with a spitball (that space cadet Charlie Hirsh apologized five times, but a ball of saliva-saturated paper is still a ball of saliva-saturated paper), and now this.

My eyes catch my reflection in the glass of Mr. Brenigan’s office door. I scowl at my brown skin, dark eyebrows and straight black hair that I’ve always felt begins too high on my forehead. As the only Indian person in the whole school, sometimes I feel I stand out like a nigella seed in mayonnaise.

I want to scream at myself, What were you thinking!?

Thing is, I have kind of a grand plan, a complete vision of how my life is going to play out. First, I’m going to get straight A’s for the next four years and then graduate high school at the top of my class, maybe even a semester early. Then I’ll go to medical school, where I’ll play classical bass in the student orchestra and, eventually, marry another Bengali doctor or maybe a college professor, somebody my parents will like. A couple of weeks ago I even started volunteering at the Opequonsett Medical Clinic, helping the triage nurses with paperwork and answering questions as people come in. It’s the kind of experience that gives a person a leg up in her Ivy League applications. You have to think ahead like that when you come from a family with high expectations.

Anyway, everything about today’s situation is horrible. What happened this afternoon definitely doesn’t fit into my long-term strategy.

Since the previous winter I’ve been secretly mooning over Scott Pickett, high school soccer star and heartthrob drummer for Mudslide Crush, sure he doesn’t know I exist. He’s two years older than me, tall with blond spiky hair and a stare that leaves me prone to walking into walls. But he was never part of my grand plan. Still, at lunch on the second week of the new school year, out of the blue he pulled up a chair next to me and started chatting. After I revived from the initial shock, we ended up talking through my entire lamb curry and rice and his baloney and cheese pita roll. He told me about his band, his friends, and his record-breaking eight goals in a 13 to 0 victory against Bristol. By the end of lunch we’d shared his Twinkies.

In the library later that day, I told my best friend, Naomi Fishmeier. But her reaction wasn’t what I’d expected.

“How come you never told me you liked Scott Pickett?” she whispered. She was putting the finishing touches on her first column for the weekly student-run newspaper, the Barking Clam. She was the self-appointed OHS Scene Queen. “You weren’t worried I’d put it in the paper, were you?”

“No, I know you’d never do that to me,” I said. “I just wasn’t ready to talk about it with anybody. But you’re the first I’ve told. Honestly.” And she was.

“Mo! You should never hold back on your best friend!”

I apologized and all was quickly forgiven.

Naomi narrowed her eyes. “You better be careful about that boy. Don’t you know he has a reputation?”

“No,” I said. “I haven’t heard a thing.”

She leaned back and tapped her pencil thoughtfully on her glasses. She wore the thickest lenses I’ve ever seen. She was almost blind without them. “Well, a good journalist can’t reveal her sources, even to a friend, but I have it on good authority that while he was going out with Lynn Westerberg, he was seeing two other girls on the side.”

I felt my heart slow down. “Are you positive?”

She shrugged. “Well, I didn’t personally catch him red-handed or anything, but I think it’s true.”

I stared at her for a moment, trying to decide what to do with this information. “No,” I said finally. “I don’t believe it. Not Scott. He’s a good guy. He’s sweet. And besides, it’s not like we’re going out or anything. We just talked.”

And so, swayed by the afterglow of the Twinkie incident, I lived the next few days on a mission. Each morning I took gobs of time preparing for school, making sure to choose exactly the right outfit. Jeans and my red patterned oxford—too casual? Short black skirt with the pink satin blouse—too come-and-get-me?

To be honest, it was exhausting.

But it paid off. At first he’d speak to me as we passed in the hallways. Never for long, and just hello and what class do you have now, things like that. I tried to act like it was no big deal. But it was. After a lifetime of social obscurity, Scott Pickett was actually talking to me. The following Thursday he walked me almost the whole way home. After that, we were pretty much a couple.

It felt like Destiny.

Which is probably why I am now sitting here in front of the Vice Principal’s office, feeling like I’m about to barf.

Here’s what happened. I was lugging my bass down to the music room for my fifth-period lesson with Mrs. Reznik when I noticed a flyer on the lemonade machine announcing the dates for the Halloween Bash in October and the Holiday Talent Show in November. Even though it didn’t say so on the poster, I knew from Scott that the band playing at this year’s Bash would be Mudslide Crush. It was going to be a big deal to a lot of kids. Mudslide Crush had almost a religious following at Opequonsett High. Of course, seeing the announcement made me think of him again. Not that I need much prodding lately for Scott to interrupt my thoughts.

A few seconds later, still studying the flyer, I sensed movement near my left ear. When I turned, there he was. Scott. Out of the blue. Fate.

Suddenly I felt tongue-tied.

Looking back on it now, it’s difficult to explain even to myself how what occurred next actually happened. But the facts are the facts:

Within moments of Scott’s unexpected appearance, the two of us were making out in the bushes behind the new gym.

Keep in mind, sitting under a rhododendron with a double bass and a soccer star several minutes after the fifth-period bell had already sounded was an act of madness unlike anything I’d ever committed before. Certainly it wasn’t part of my plan. Up until that moment I’d always pretty much thought of myself as a model of good behavior, a girl who never let her parents down. This juvenile delinquent with leaves in her hair was a stranger to me. In fact, other than one brief, hot moment at the end of my street the day Scott walked with me, I’d barely even let him kiss me. But something in the smoldering look in his eyes, the casual way he took my hand and gently tugged me toward the exit took me by surprise and swept me into a moment of pure insanity. In a way, I didn’t feel like I had any choice.

I was like one of those helpless Victorian ladies unable to stop herself from meeting the vampire at the window.

Still, as I gasped for air in the bushes, a secret part of me was ecstatic about this new development. For that moment at least, it felt freeing to let go, to give in to my innermost passions. Plus, one of the undeniable side effects of being romantically connected with Scott Pickett is that it means you’re somebody. Now, I’ve never exactly been at the center of everybody’s radar screen. Being part of the trendy crowd was never my focus—I always had longer-term goals in mind. But now that I actually had a shot at joining the social elite, I was surprised at how thrilling it felt.

That is, until Mr. Yezzi, the Poli Sci teacher, happened to look out the window. When he saw us he started pounding on the glass.

So now here I am, summoned to the front office for the first time ever. Scott’s in there with Mr. Brenigan now, but it’s only a matter of time before it’s my turn.

My headache is stronger now. I pick at a tiny woodchip lodged in the fabric of my Capris. With one unlucky spin of the Wheel of Fortune I’ve plummeted from perfect happiness to absolute despair. There I was, living my perfectly respectable under-the-radar life, but then I had to go and throw it away. Sure, getting in trouble with a soccer star could potentially catapult me into the popularity stratosphere, but at what cost?

And what about Mrs. Reznik? Odd as she is, I’m lucky she agreed to give me individual bass instructions as an independent study. What will she think when she hears that I skipped Antoniotti’s Sonata No. 10 in G Minor for a smooch in the dirt? Will she change her mind about working with me? The school already cut the Orchestra program this year, and my parents certainly can’t afford private lessons.

And my parents? I never told them anything about Scott, of course—a fact that sends a gush of guilt through my intestines whenever I think about it. Normally I don’t keep secrets from my parents. But they grew up in Calcutta, the land of the arranged marriage, and they don’t even want me alone with a boy, let alone dating. And as antiquated as their old-world views may sound, I respect my parents and hate to disappoint them. Telling them about Scott and me would break their hearts. So even though I feel sick about it, I’ve been keeping this whole thing a secret—what else can I do?

If they get wind of any of this, I’m dead.

The door eventually opens and Scott appears, his confident smile completely at odds with the knots in my gut. Mr. Brenigan waves me in. Scott passes me and whispers, “No big deal. Just detention.”

Great. Another first.

I leave Mr. Brenigan’s office about ten minutes later, my head pounding so hard I shoot straight to the bathroom and lock myself in one of the stalls until the feeling passes. After that, I calm down a little. I spend the final two periods of the day thinking about the silver linings: First, I was able to convince Mr. Brenigan not to call my parents. And second, even though we’ll be in separate rooms, at least Scott and I will be in detention together.

Maybe I’ll even see him again when it’s over.

It was the next day at school when I fully recognized what a terrible mistake I’d made.

It was the next day at school when I fully recognized what a terrible mistake I’d made.

Imagine the scene: There was our heroine, Sista Stella the hopeless reprobate, newly sheared and wrapped in her stepfather’s castaway snakeskin jacket. As she walked the school hallways the other kids drifted to the far side of the corridor as if terrified. Nobody even made eye contact. Our protagonist pretended not to notice, but even the teachers looked at her with suspicion. It occurred to her that when it comes to oversized girls with unconventional hair and snakeskin jackets, it wasn’t as if this town had a corner on the market. But now she felt exposed and naked. What’d she been thinking, cutting her hair like that? Instead of fixing her problem, she made it much worse. Now she felt more out of place than ever.

Worst of all, there was no going back.

And now I can hear the cry from the rafters: “Tell us more, Sista! What happened next to the poor, misunderstood girl?”

All right, my devoted friends. I’ll tell you.

Just because I knew I’d destroyed any chance I had of fitting in, didn’t mean I’d changed my mind about taking action. For one thing, I was still furious with Mr. Brenigan. In fact, the previous evening I’d mapped out a strategy for exposing him as the thoughtless dictator he was. And as crappy as I felt that day, I decided I would still carry it out.

Why not? I had nothing to lose.

I knew that the ninth and tenth graders had an assembly on Personal Safety and Empowerment that afternoon. I made sure I was one of the first through the gym doors so I could take a front-and-center seat on the bleachers. As the freshmen and sophomores piled in, Mr. Brenigan leaned against the opposite wall looking bored. When he glanced in my direction I pretended to be interested in the palm of my hand.

For a long time nobody sat near me. Finally, having no other choice, a group of five girls, every one of them wearing hip-huggers, shuffled over. But when it looked like a tight fit for all of them, they tried to shove me to one side like they owned the place. “Find another seat, freak,” barked one of them, a particularly beefy girl.

I didn’t say anything. I just gave the girl the evil eye.

It wasn’t long before the pompous princess looked a little less sure of herself and backed down. Soon, her friends exchanged worried looks, and a moment later, they squeezed into their seats without another unkind word. It occurred to me that there was at least one advantage to having crazy hair and a snakeskin jacket in the beehive of cliques and tyrants known as Opequonsett High School.

Eventually the principal, Mrs. Ledlow, an undersized woman with giant round glasses, appeared at one end of the room. She raised her hands and her voice boomed from four giant overhead speakers. “Boys and girls,” she said, “I hope you’re enjoying our brand-new, modern gym!”

During the applause that followed, I scanned the room. The gymnasium really was spectacular, with a glass cathedral ceiling, a shiny new floor, cushy bleachers, a mammoth sound system and even an impressive snarling quahog, the school’s clammy mascot, painted in majestic gray and blue at center court. Everybody knew that building this new gym had ended up costing the town much more than they’d budgeted. Their solution was to cut back on other programs, like music.

Which spoke volumes about screwed-up priorities.

Finally Mrs. Ledlow asked everyone to show respect for our award-winning guest presenters by giving them complete silence. She went back to her chair and the lights dimmed. Then in a sudden torrent of sound, Dick Dale and His Del-Tones came roaring through the overhead speakers. I was pleasantly surprised. For a few seconds everybody sat in the dark listening to delicious middle-eastern guitar riffs like the start of an Arabic surf adventure. It was “Miserlou,” and my hands knew every twist and turn. But then, from unseen corners of the room, five or six wide-eyed men and women dressed in black overalls and white face paint wordlessly bounced, unicycled, danced, crawled and pretended to swim their way to the pyramid of sports equipment arranged at one end of the gym floor.

Apparently a troupe of clown-faced mimes dribbling basketballs to surf music had something to do with safety and empowerment.

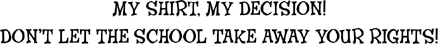

By then my heart was pounding in my chest. What I was about to do was a risk, a bold act of defiance that would undoubtedly have repercussions. In my unhappiness and confusion, I admit I considered chickening out. But the moment passed. Within seconds, before the clowns got too far into their act, I stood up and strolled four or five paces onto the parquet floor, then turned around and threw off my jacket. I was wearing the very same T-shirt that had so traumatized the delicate sensibilities of the administration only the day before. Next I unfolded a cardboard sign I’d prepared, holding it up for everybody to see. In case there was anyone at the back with bad eyesight, I shouted the words over the music:

As I’d expected, there was an immediate uproar.

Some of the teachers jumped out of their seats and ran toward me. At first most of the kids in the bleachers just looked surprised, but within seconds it seemed like the entire wall of them stood up and yelled. Some laughed, some waved their fists, and a few grinned and applauded.

“We’re human beings, not cattle!” I called out, surprised at the pleasant rush I felt. I was enjoying the chaos.

The music stopped and the lights came on. Suddenly Ms. Stone, the algebra teacher, stood very close. “What do you think you’re doing?” she spat up at me. “You’re disturbing our assembly!”

I could feel the blood pulsing through my veins. In the excitement, it took a moment to focus my thoughts. What exactly was I doing? But then it came to me.

“I … I’m trying to change the world.”

Mr. Brenigan, his face purple, appeared huffing and puffing behind her. Less than thirty seconds later, they walked me to the exit doors. I glanced over at the mimes as we passed them. They didn’t seem overly concerned. They were just following my progress across the floor, apparently waiting for the anarchy to work itself out so they could start again. In fact, I could almost swear that one of them gave me the thumbs-up sign.

But my newfound boldness was short-lived.

Minutes later, I sat quietly in Mr. Brenigan’s office while he read me the riot act. Away from the shouting crowds, I began to question the wisdom of my protest. What was I trying to prove, anyway? It wasn’t as if the school rules were going to change. And when he sentenced me to a full week of detention, I felt all the fear and unhappiness I’d been wallowing in ever since school began well back up inside me. Plus, I hated to imagine how mad my mother would be when she learned how much trouble I’d gotten myself into. As Mr. Brenigan’s stern voice droned on about disappointment and harsher punishments to come, I felt Sista Stella deflate inside me.

Soon after that, I was back in class just as friendless and alone as ever. Perhaps there was a little more whispering when I walked into the room, but other than that, nothing much had changed except that now I was a certified, publicly acknowledged freak. As I took my seat I could feel in my pocket the envelope that contained the documented proof of my own foolishness.

Eighty-four.

As if any more proof were needed.

Mr. Prichard gave me detention for swearing in class. That meant I wouldn’t be able to go to the band tryouts that afternoon unless I cut detention. And this wasn’t even the worst of it. My problems were so much bigger now.

Mr. Prichard gave me detention for swearing in class. That meant I wouldn’t be able to go to the band tryouts that afternoon unless I cut detention. And this wasn’t even the worst of it. My problems were so much bigger now.

It wasn’t long after the incident that I found out just how badly I’d screwed up my life.

The humiliation was unbearable.

Thing was, last year I’d kind of screwed things up with my two closest buddies and now I was a little short on friends. That’s why I’d been so determined to fit in this year. Until today I’d been imagining popularity, envisioning tables of kids turning to wave to me as I entered a room. But instead, kids were veering away from me. And I couldn’t blame them. To be seen with me was committing social suicide. And it was all Sydney’s fault. I knew I should just get over it, but I couldn’t. I’d stuffed the envelope with the drawings under a pile in my locker, but even now when I closed my eyes I could still picture her face.

I know it sounds funny, but I was furious. It wasn’t fair. Could I help it if for some infuriating reason I had a thing for my dad’s girlfriend?

I’d been condemned to social purgatory and it was all because of her.

After the seventh-period bell I stood in the hall halfway between the gym, where the Marching Band tryouts were about to start, and the stairway to the basement, where freshman detention was about to begin. I felt paralyzed with indecision.

Azra Quimby appeared from the crowd, her stuffed backpack over her shoulder. She came right up to me and just stood there, which kind of freaked me out. Finally she said, “Excuse me, Wen. You’re standing in front of my locker.”

“Oh.” I stepped aside. “Sorry.”

Azra and I had kind of a weird relationship. We used to be best friends. Along with another girl, Floey Packer, we’d been kind of a threesome, almost inseparable. But that all ended last year when I’d made the mistake of asking Azra out. Now that we’d broken up, everything was uncomfortable between us.

A few seconds later she was crouched down, pulling things out of her backpack. Without looking up at me she said, “What are you doing here? Don’t you have detention?”

“Oh, you heard about what happened?”

She nodded. “Everybody heard.”

Another wave of shame washed over me. But I refused to let it show. “I’m trying to decide what to do. Today is Marching Band tryouts. Should I really forget about band and go to detention like I’m supposed to, or should I skip detention, accept whatever the consequences may be, and go to tryouts like I’d planned? What do you think?”

She stood up, her backpack restuffed and rearranged, and slammed her locker door shut.

“I don’t know,” she said, barely looking at me. “But I gotta get going or I’m going to miss my bus.”

So much for sympathy.

Alone again, I realized I didn’t have much time left. In less than four minutes the after-school activities bell would ring. So I took a deep breath, gripped hard on my trumpet case handle, and made my decision.

I ran toward the gym.

When I got to the open double doors, I could see a crowd of kids, each with instrument cases at their sides, standing around a table set up at one end of the gym floor. Jonathan Meuse stood in the thick of it like a scarlet-haired king holding court. He was already explaining how the Marching Band budget was smaller this year, so anyone who got in this year would be expected to sell a lot more chocolates than ever to pay expenses. But then he noticed me at the door.

“Oh, look who it is, folks!” he called. “Wendel Gifford, our own resident artist and admirer of the human form! You here for the tryouts, Michaelangelo?”

Everybody turned. A bunch of kids laughed.

Suddenly my legs turned to jelly. I felt every molecule in my body shrivel up. It occurred to me as I scanned the grinning faces that I might be better off spending my after-school time alone at home in front of the TV.

“No,” I said, lamely, backing into the hallway. “I … uh … have detention.”

As soon as I was out of sight I started running, my head as warm as a brick oven. I couldn’t get away from there fast enough. When I came to my locker I stopped, yanked open the little metal door, shoved my trumpet and case violently inside, and then slammed the locker door shut again. For a few seconds I just stood there with my forehead pressed against the cold metal.

There’s something incredibly humiliating about not being cool enough to try out for Marching Band.

A moment later I dragged myself toward the basement stairway. I figured I still had a half a minute or so before the bell.

Dear Naomi,

Let me start off by saying that I don’t believe in accidents. I’d hate to think that whatever happens is simply the inadvertent outcome of a series of random events with no preordained purpose. Anyway, there’s too much evidence against it. I’m not saying that the future is already decided, only that each decision we make, however small, helps clear the path toward events that inevitably follow. For example, if I hadn’t skipped American Lit, I wouldn’t have had to show up to detention that afternoon. And if I hadn’t gone to detention, everything would have been different.

But the fact was, Mr. Carr assigned The Great Gatsby, a sad, beautiful story I’d already read at my old school. Plus, he liked to quiz us after each chapter and there’s no better way than that to strip away all the fun of a good book. Which was why I chose to skip third period and spend the time curled up on a bench behind the janitor’s equipment room finishing it for the third time. Which in turn was why, when the principal, Mrs. Ledlow, happened to make a rare visit to that corridor, she found me there. And that was why, at 2:05 that afternoon, I had to show up to the basement for ninth-grade incarceration. Where Lemonade Mouth was born.

How could all that have been dumb luck?

I like to think that whatever happens was always meant to happen, like an unstoppable train that departed long ago and forever rolls toward an inevitable destination. Life seems so much more romantic that way, don’t you think? Still, you asked me to tell my story so I guess I need to begin it somewhere. That afternoon in detention is as good a place as any.

Detention that day was downstairs with Mrs. Reznik, the music teacher. When I walked into the music room, a cluttered, windowless basement space near the A.V. closet and the school’s boiler room, the little radio on Mrs. Reznik’s desk was playing a commercial with a catchy jingle, that “Smile, Smile, Smile” one about teeth. It kind of stuck in my mind. That’s not unusual for me. There’s always some tune or other drifting around in my head.

Anyway, just as the bell rang I took a seat near the back. I was trying to concentrate on my breathing. I sometimes get panic attacks in stressful situations and right then I needed to keep calm. Nobody spoke. Mrs. Reznik sat at her desk, coughing and scowling as she leafed through a giant pile of paperwork. A tiny, narrow-faced lady with a body shaped like a piccolo, skin like worn shoe leather, and a startlingly large nest of lustrous brown hair, she was a sight to behold. I’d seen her reduce kids to tears with one look. There were rumors that the school administration had been trying to force her into retirement, but they couldn’t get rid of her. I could understand why. The woman scared the pee out of me.

I studied the blackboard where she’d set down the law in sharp, spidery chalk letters.

1. No gum chewing, food or drink in the classroom.

2. You will remain seated.

3. You will not talk.

4. The first time you break a rule, your name will go on the board. The second time, you will receive another detention.

At my old school, St. Michael’s in Pawtucket, they didn’t even have detention. St. Michael’s is an alternative school, a place where they send kids who don’t fit in somewhere else so they can get an education “without walls.” But Brenda, my grandmother, told me back in July that we couldn’t afford the tuition anymore so now I found myself back among the walls.

My chair squeaked and I almost jumped. Mrs. Reznik looked up. “Name please?”

The other detainees, two boys and two girls, turned to look. I tried to smile. I may have been an introverted Virgo of the worst kind, but at least I was working on it.

“Olivia,” I reminded her. “Olivia Whitehead.”

Mrs. Reznik frowned and scribbled something on a piece of paper. “You can all read the rules. I suggest you use this hour to work on something productive.” Some pop song came on—Desirée Crane or Hot Flash Smash, somebody like that. Still, it was the “Smile, Smile, Smile” commercial that looped through my mind.

The other kids went back to staring into space. I only recognized two of them. Wendel Gifford, a kid who always seemed to dress in crisp, preppy clothes, was in my Social Studies class. We’d never actually spoken, but he’d embarrassed himself during a presentation that morning and I felt sorry for him. The Amazon girl with the leather skirt, savagely ripped tights, and short spiky hair was Stella Penn. After she’d pulled that crazy stunt at an assembly earlier that week, everybody knew who she was. The other two I didn’t know. Tapping nervously on his desk at the far end of the front row sat a sullen, thick-necked boy with an overgrown mop of frizz. To my left fidgeted a skinny Indian-looking girl with long dark hair, big brown eyes and, at her feet, a huge, gray double bass case. She was biting her nails like a stress-fiend.

After a while, Mrs. Reznik went into a coughing fit. They were dark, rumbly coughs that seemed to come from deep in her chest. Everybody looked up. After a moment she stood and stepped toward the door. “I’ll be back in one minute,” she said, still coughing, and then left the room. When she came back she seemed better. In her hand was a green and yellow paper cup that said Mel’s Organic Frozen Lemonade. It must have come from the machine I’d noticed at the top of the stairs. She set it on her desk and sat down.

I guessed the no-drinks rule didn’t apply to Mrs. Reznik. Not that I was going to say anything.

Wen and Stella stared vacantly at the wall, the frizzy-haired boy tapped on his desk and the skinny girl absently fingered a pile of rubber bands. In a poster hanging near my chair, four old guys in short pants and feathered hats were playing accordions and tubas under this huge willow tree in the middle of what looked like some quaint, pastoral German village. I gazed at it and imagined myself into the picture. I’m pretty good at that, imagining myself somewhere I’m not. I find I can visit the nicest places that way. In my mind I was relaxing on the ground in front of the four guys, listening to their music and feeling the grass between my toes and a gentle breeze in my hair. Soon, the music transformed into the tooth song and I realized the commercial had come back on Mrs. Reznik’s radio again.

Smile, smile, smile!

Would you like the perfect smile?

Don’t you want your first impression to be great?

I looked up. Every head in the room was nodding with each oomp-oomp-oomp of the tuba.

Bernbaum Associates, Bernbaum Associates, Bernbaum Associates

Can fix your smile—Don’t Wait!

Soon after that, Mrs. Reznik’s cell phone rang. She put it to her ear and a second later she stepped out of the room again to take it, only this time she switched off the radio before she left. It took me a minute or so to adjust to the silence. My eyes drifted back to the rules again, and I found myself pondering Mrs. Reznik’s skinny D’s and the steep slope of the tops of her T’s when I suddenly noticed that something felt wrong. I looked around.

Everybody in the room was looking at me.

That’s when I realized I’d been singing the smile song. My face went warm. After a moment, Stella laughed. Wen shrugged kindly and turned back around, and then everybody else did too. I wanted to die.

There are different opinions about what happened next.

Mo, who of course I now know was the skinny girl, says it was Charlie, who at that time I only knew as the frizzy-haired boy, tapping on his desk that started it. Charlie says it was Mo. She picked out a rubber band, stretched it between her thumbs and flicked it with her fingers. By changing the length she altered the pitch, making the same bouncing notes as the tuba in the commercial. I don’t remember who was first, but it doesn’t actually matter because before long they were doing it together. And it sounded good.

Boom tappa boom tappa boom.

Oomp-oomp-oomp.

Stella and Wen looked up. The next thing I knew, Stella shot out of her seat. She hopped over a row of desks to where Charlie sat.

“What are you doing?” he whispered, shrinking back from her. I wondered if he thought she was going to hit him. Big as he was, Stella looked like she could take him.

“Don’t stop tapping!”

On the wall over his head hung a beaten-up ukulele. She reached across, grabbed it off the hanger and took it back to her seat. After adjusting the tuning pegs, Stella started strumming the chords of the jingle along with Mo and Charlie. The ukulele sounded tinny and crazy. But in a good way.

By that time I guess Wen wanted to get into the act. He went to the storage closet and rummaged around. Eventually, with a big silly grin, he held up a kazoo.

“Yes!” Stella whispered.

Still plucking her rubber band, Mo giggled. I kept glancing over my shoulder at the door, expecting Mrs. Reznik back any second. They played through the full song—the verse and even the Bernbaum part. Wen had the melody. It was a joke, but it still worked. The music from their makeshift instruments sounded so unusual, so exciting. My heart pounded. I suddenly didn’t care if Mrs. Reznik showed up.

The next time the verse began, I sang the words.

Smile, smile, smile!

Would you like the perfect smile?

Don’t you want your first impression to be great?

Hearing myself sing in front of people felt weird. I’d never thought I had a very pretty voice. Instead of a pure, clear sound like the singers in, say, a Disney cartoon, mine is kind of low and scratchy, like a three-pack-a-day smoker. It’s always been that way, even when I was little.

But Stella nodded, Wen winked and everybody was grinning.

Then dial, dial, dial!

Change your life, improve your style!

Call our dental experts ’fore it gets too late!

It felt like one of those perfect moments where everything comes together. But like I said, I don’t believe in accidents. Even if this strange, musical moment, the final result of a long chain of seemingly unlikely events, never came to anything else, it was meant to be.

Something new had been born.

We were just starting over again when Charlie suddenly lost his grin and stopped tapping. I looked behind me.

Mrs. Reznik was standing in the doorway.

In the silence that followed, it was obvious she’d heard us. We waited for her to speak but she only stared, wide-eyed. Something important had just happened. Looking back, I could feel it even then. I think we all could. Only nobody knew what it was.

And none of us could have imagined it would change our lives forever.