6

The Power of Getting Started

Just get started.

I DON’T HAVE TO look very far for a story about this topic. My own life supplies many examples daily. When I face a task that I find aversive, a task I simply don’t want to do, a task that I find boring or tedious, or even a task for which I have doubts about my competence, it is tempting to walk away. I want to procrastinate. I find myself saying things like this to myself: “I’ll feel more like doing this later.” This is a flag for me. It is a signal that I have learned to identify that I am just about to procrastinate. At that very moment, I use this signal to just get started. I will immediately start on anything related to the task at hand. Let’s explore why this is so important.

Issue

Once we start a task, it is rarely as bad as we think. Our research shows us that getting started changes our perceptions of a task. It can also change our perception of ourselves in important ways.

In a series of studies, my students and I used electronic pagers to gather what is called experience-sampling data. We paged research participants randomly throughout the day over a week or two. Each time we paged them, we asked things like: “What are you doing?” “Is there something else you should be doing?” “How are you feeling?” “What are you thinking?” In addition, depending on the study, we asked the participants to rate what they were doing and what they were supposed to be doing on things like how stressful they perceived the task to be. A rating of 10 indicated extremely stressful, while a zero meant not stressful at all (and all points in between reflected the variability).

This type of data allowed us to take a sort of snapshot through time of what the participants were doing. Importantly, we also got a real-time glimpse of what they were thinking and feeling. Some of our findings were expected. Some surprised us. I have summarized these findings by simplifying the research as a Monday-to-Friday process and by focusing mainly on the task avoidance.

As expected, on Monday when participants were avoiding some task(s) (e.g., working on an assignment) in preference to other activities (e.g., hanging out with friends), we found that they typically said things like “I’ll feel more like doing that tomorrow” or “Not today. I work better under pressure.” As you learned in the previous chapter, we rationalize the dissonance between our behaviors (not doing) and our expectations of ourselves (“I should be doing this now”). Of course, later in the week, none of the participants spontaneously said things like “I feel like doing that [avoided task] today” or “I’m glad I waited until tonight, because I work better like this.”

Surprisingly, we found a change in the participants’ perceptions of their tasks. On Monday, the dreaded, avoided task was perceived as very stressful, difficult, and unpleasant. On Thursday (or the wee hours of Friday morning), once they had actually engaged in the task they had avoided all week, their perceptions changed. The ratings of task stressfulness, difficulty, and unpleasantness decreased significantly.

What did we learn? Once we start a task, it is rarely as bad as we think. In fact, many participants made comments when we paged them during their last-minute efforts that they wished they had started earlier—the task was actually interesting, and they thought they could do a better job with a little more time.

Just get started. That is the moral here. Once we start, our attributions of the task change. Based on other research, we know that our attributions about ourselves change, too. First, once we get started, as summarized above, we perceive the task as much less aversive than we do when we are avoiding it. Second, even if we do not finish the task, we have done something, and the next day our attributions about ourselves are not nearly as negative. We feel more in control and more optimistic. You might even say we have a little momentum.

Research by Ken Sheldon (University of Missouri, Columbia) also demonstrates that progress on our goals makes an important difference. Progress on our goals makes us feel happier and more satisfied with life. Interestingly, positive emotions have the potential to motivate goal-directed behaviors and volitional processes (e.g., self-regulation to stay on task) that are necessary for further goal progress or attainment. Very clearly we can see how if we “prime the pump” by making some progress on our goals, the resulting increase in our subjective well-being enhances further action and progress.

Of course, this simple advice is not the whole solution to the procrastination puzzle, but it is a crucial first step toward solving it and decreasing our procrastination. In the next chapter, I take us past this initial step.

STRATEGY FOR CHANGE

When you find yourself thinking things like:

“I’ll feel more like doing this tomorrow,”

“I work better under pressure,”

“There’s lots of time left,”

“I can do this in a few hours tonight” . . .

let that be a flag or signal or stimulus to indicate that you are about to needlessly delay the task, and let it also be the stimulus to just get started. This is another instance of that “if . . . then” type of implementation intention.

I’ve raised the notion of an implementation intention a few times already, but I have not provided details about what it is. As defined in the well-developed psychology of action created by Peter Gollwitzer (University of New York), an implementation intention supports a goal intention by setting out in advance when, where, and how we will achieve this goal (or at least a subgoal within the larger goal or task).

It is not as effective to make ourselves a “to do” list of goal intentions as it is to decide how, when, and where we are going to accomplish each of the tasks we need to get done. There is an accumulating body of research by Peter Gollwitzer and his colleagues that demonstrates the efficacy of implementation intentions for initiating behaviors, including following through on the intentions to take vitamins, participating in regular physical activity after surgery, and acting on environmentally minded intentions such as purchasing organically grown foods. In short, implementation intentions are a powerful tool to move from a goal intention to an action.

As I have outlined in earlier chapters, these implementation intentions take the form of “if . . . then” statements. The “if” part of the statement sets out some stimulus for action. The “then” portion describes the action itself. The issue here really is one of a predecision. We are trying to delegate the control over the initiation of our behavior to a specified situation without requiring conscious decision.

IF I say to myself things like “I’ll feel more like doing this later” or “I don’t feel like doing this now,” THEN I will just get started on some aspect of the task.

Notice that we are not using the famous Nike slogan of “Just do it!” It’s about just getting started. The “doing it” will take care of itself once we get going. If we think about “just doing it,” we risk getting overwhelmed with all there is to do. If we just take a first step, that is much easier.

As a strategy, you may find that you have to just get started many times throughout the day, even on the same task. This is common. Even in meditation, we have to gently bring our attention back to our focal point, whatever that may be (e.g., our breath, a mantra). The thing to remember is that just getting started may happen many times in a day.

All of our procrastination gets stopped short when we just get started. It is not the whole solution by any means, but it is a huge and crucial first step. As is commonly said, “A job begun is a job half done.”

It is tempting to run away from this strategy, to criticize it because it is exactly your problem. You are not able to get started.

Not so. You think you are not able to get started, probably because you are focused on your feelings (which are negative), and you are thinking about the whole task, about “getting it done” as opposed to “getting started.” The trick is to find something that you can get started on.

Keep it really simple. Keep it as concrete as possible, too. Research by Sean McCrea (University of Konstanz) and his colleagues has shown that thinking abstractly about our goals leads us to believe that they are not that urgent or pressing. More-concrete thoughts about your goal or task, more-concrete plans, lead to more timely action. In other words, more-concrete plans will help you to just get started.

An implementation intention helps you get started. It is your predecision so that you do not get caught up in thinking, choosing, deciding. You have already made the decision. Now is the time to act.

Here is a common example from an academic context: When facing a writing task, perhaps a term paper, it is possible to just sit and stare at a blank computer screen. As you do, anxiety builds, and pretty soon you are giving in to feel good. You are away from your desk another day, and guilt is building fast.

So instead of staring at that blank screen, start typing. Start with a title page. Put your name on it. Add the title if you know it, at least something as a working title. Begin your reference page if you are still not ready to write. Begin jotting down ideas about what you would write about if you could write. You do not have to write sentences, but you can if they come. The thing is, you are now actually working on the task. It is rough, but everything begins that way, rough. Carpenters rough-frame houses. Sculptors carve and shape rough surfaces into smooth ones. Farmers disk and harrow rough, plowed fields into fields ready for planting. We are always starting somewhere to work toward the finished product.

The other way to think about this is the old saying that “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Take that first step. Just get started. It can make all the difference.

Honestly, if you are not ready to make this first step, to just get started on a day-to-day, moment-to-moment basis, then put this book down now. You are not committed to change yet, and nothing else I have to say will matter in your self-change. Don’t get me wrong, I am not trying to discourage you. I am just being honest.

I will tell you more about other strategies, the role of willpower, and even the effects of our personalities on procrastination in upcoming chapters, but you must know that it will always come down to that precipitous moment when you just get started. It will always come down to that movement from not doing to doing. For tasks that we would rather avoid, this is a difficult but wonderful moment.

So we are back to where I began the chapter, with the mantra “Just get started.” To this I have added a couple of other phrases that you might want to use as your own personal mantra. These are: “Prime the pump”; “A job begun is a job half done”; and “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

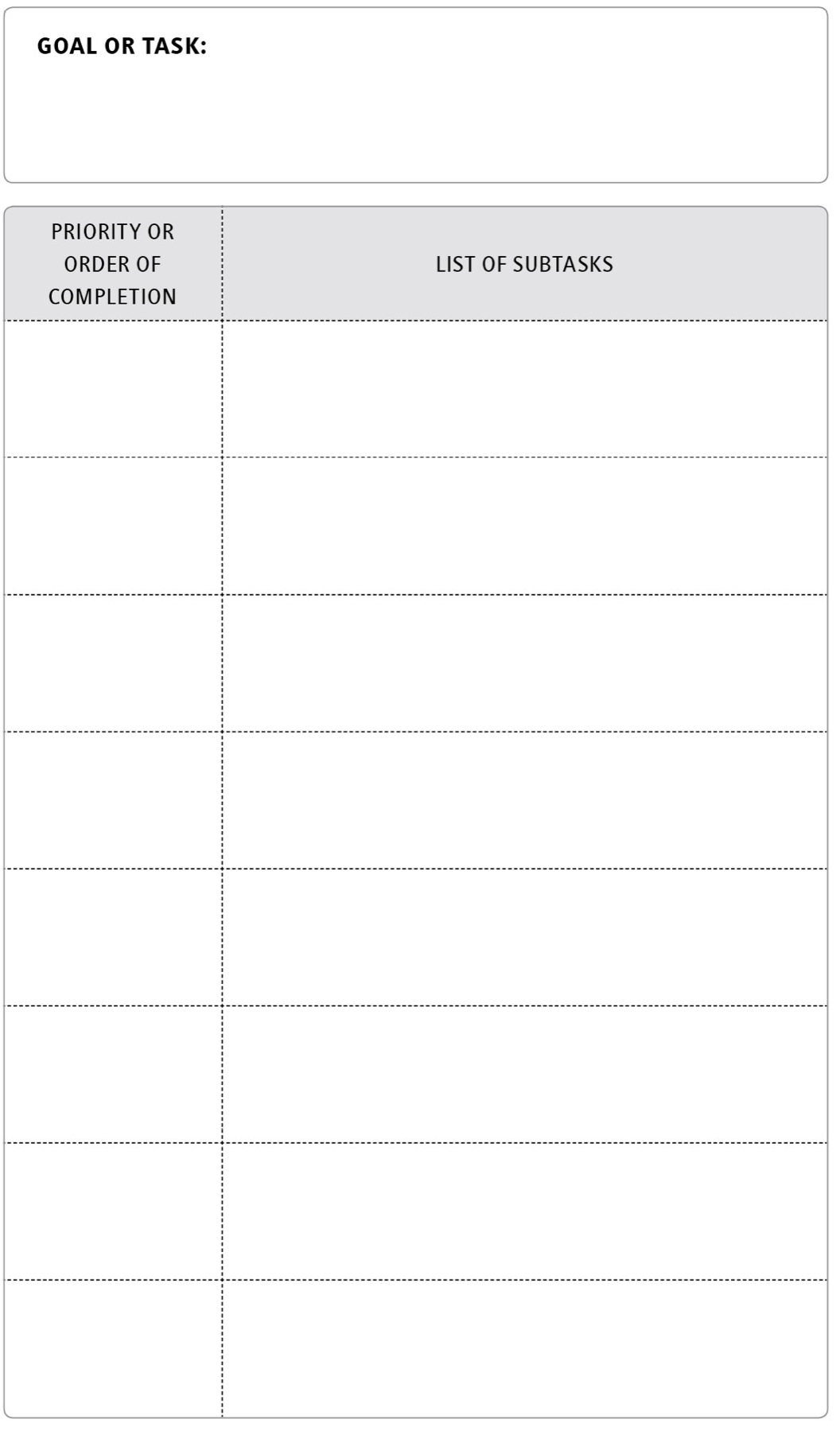

In the table that follows (or as a thought experiment), pick a task (or goal) that you are procrastinating on and that is really bothering you. Write down as many of the subtasks that you can think of that are required to get this task done. Now you might use the first column to indicate which subtask is your priority or which subtask makes the most sense for you to complete first. This is the place to just get started. However, even with this list of tasks, you may not know how to proceed. This is simply a reality, and it may not be possible to be completely rational in your approach, but you can still get started. Pick a task, any task, and let that suffice. You may even have to flail around a bit, but if you get started, at least you will find your way. Not starting will guarantee that you will remain stuck. You can take this approach for just about any goal or task that you have.

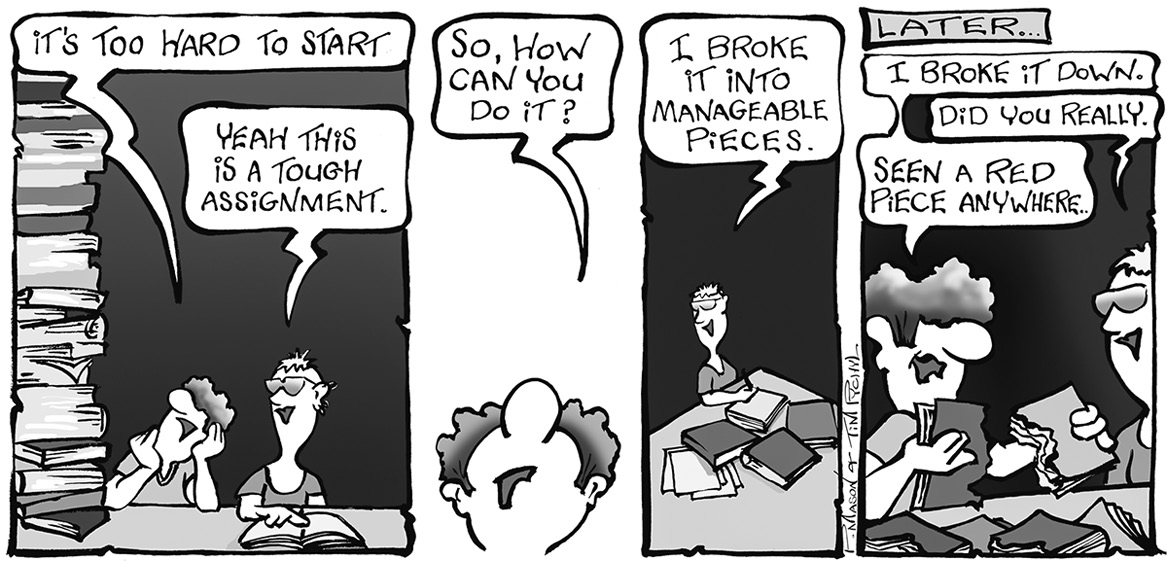

In fact, when you just cannot seem to get started on a task, get started by breaking down the task into subtasks. BUT don’t stop there, as tempting as it may be some days. It is true for many of us that after we make a list like this, we feel better and we think we have accomplished something, so we actually stop—another excuse for procrastination. Don’t forget: The purpose of that list is to get you started.

Just get started.