8

Willpower, Willpower: If We Only Had the Willpower

Willpower is a limited resource that I need to use strategically.

RACHEL’S EXERCISE GOAL WASN’T becoming a reality. Given her very early start each day to get the kids off to school and out to work herself, she put aside time after dinner to get on the treadmill. However, after an exhausting day in her law firm along with the day-to-day challenges of orchestrating school, day-care schedules, and the many household chores she shares with her husband, she couldn’t seem to muster the “get up and go” to get up and go. She was frustrated. She just didn’t seem to have the willpower to get off the couch. Every night she put it off again, hoping tomorrow would be different.

Issue

Willpower is a limited resource. I think many of us know this from experience. Roy Baumeister (Florida State University), as well as his students and colleagues, have demonstrated this in a series of clever experiments. It is worth reviewing these to make the point.

In the typical experiment, research participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups. Both groups expect that they will participate in two tasks, but there is an important difference between the groups in terms of the self-regulation demanded of them in the first task.

In the first task, the participants in the experimental group are required to self-regulate a great deal, whereas the participants in the control group are simply asked to do the task. For example, participants in both groups may be asked to watch a funny film, but the participants in the experimental group would be required to self-regulate by suppressing their emotional expression, while the participants assigned to the control group would be given no specific instructions about how to react. In a similar study, participants in both groups arrive hungry, but the experimental group is invited to eat radishes while resisting a tempting plate of cookies, whereas the control group is allowed to eat the cookies or the radishes (you guess which is more popular). In each of these experiments, the participants in the experimental group exercise self-regulation while the participants in the control group do not.

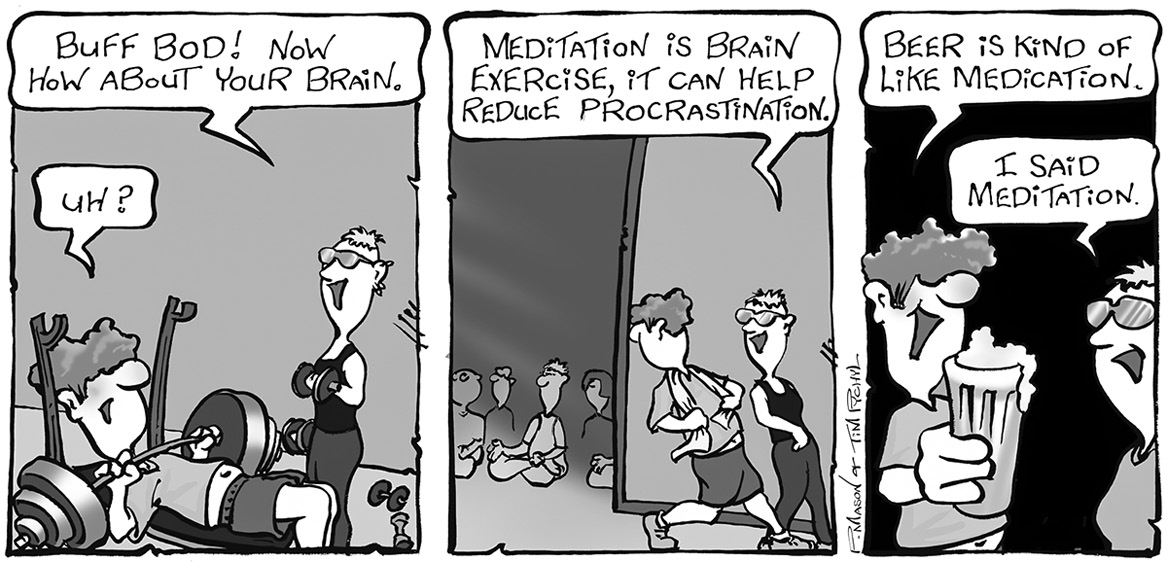

Once this first task is completed, both groups are asked to complete a second task that involves self-regulation. Participants in both groups need to self-regulate their behavior to achieve success, and the key outcome measure is how persistent participants in each group are. For example, typical second tasks include things like complex figure tracing, solving complex anagrams, drinking an unpleasant (but not harmful) “sports drink,” and, my favorite, resisting drinking free beer (a driving test is expected to follow). The main idea is that this second task requires self-regulation, and the hypothesis is that the participants in the experimental group will perform more poorly (not persist as long) because they have already exhausted their ability to self-regulate.

The findings of these studies consistently demonstrate that the participants in the experimental group perform at a lower level than the control group. Given the difference in the self-regulatory demands of the first task, the researchers conclude that the participants in the experimental group have exhausted their self-regulatory strength, at least temporarily, and therefore are unable to muster the self-regulation required for the second task.

In a practical real-life example of this, one study showed that after coping with a stressful day at work, people were less likely to exercise and more likely to do something more passive like watching television. This takes us back to where we began, with Rachel. No wonder she cannot muster the “get up and go” to exercise. She has exhausted her willpower.

STRENGTHENING OUR WILLPOWER—THE ROLE OF MOTIVATION

The self-regulatory impairments I discussed in the research above are eliminated or reduced when participants are highly motivated to self-regulate on the second task. For example, when participants are paid for doing well on the second task or they are convinced that their performance will have social benefits, they perform well despite the apparent self-regulatory exhaustion from the first task.

The key thing about these findings is that they indicate that self-regulatory depletion may be reducing motivation. Given that depleted self-regulatory strength may leave us feeling like we won’t succeed, “we’re too tired to try,” it may be that the reduced expectancy of success undermines our willingness to exert effort. It’s not that we are so impaired that we cannot respond. It’s that we “don’t feel like it.”

Sound familiar? “I’ll feel more like it tomorrow.” This is a common phrase we use to rationalize our procrastination. Perhaps it simply captures our perceptions of self-regulatory strength at the moment. Of course, it is a perception and, I argue, at least partly an illusion. It’s about our motivation to muster the self-regulatory effort—unwilling perhaps, not unable.

From this perspective, what we see is that we may fail to self-regulate because we acquiesce. In the case of procrastination, we find resisting the urge to do something else (an alternative intention) impossible to resist, so we give up and give in.

STRATEGIES FOR CHANGE

We all feel depleted throughout the day. We all have moments where we think, “I’m exhausted and I just can’t do any more” or “I’ll feel more like this tomorrow.” This is true; this is how we are feeling at the moment. However, successful goal pursuit often depends on our moving past these momentary feelings of depletion.

Given the role of motivation in self-regulatory failure, it is crucial to acknowledge the role of higher-order thought in this process, particularly the ability to transcend the feelings at the moment in order to focus on our overall goals and values. In the absence of cues to signal the need for self-regulation, we may give in to feel good, and stop trying.

It is exactly when we say to ourselves “I’ll feel more like it tomorrow” that we have to stop, take a breath, and think about why we intended to do the task today. Why is it important to us? What benefit is there in making the effort now? How will this help us achieve our goal?

From there, if we can muster the volitional strength for one more step, that is, to “just get started,” we will find that we had more self-regulatory strength in reserve than we realized. Our perception can fool us at times, and this self-deception can really be our own worst enemy.

Here are some strategies that you might use to muster what feels like the “fumes” left in your own willpower gas tank.

- The “willpower is like a muscle” metaphor is a good fit, as the capacity for self-regulation can be increased with regular exercise. Even two weeks of self-regulatory exercise has improved research participants’ self-regulatory stamina. So take on some small self-regulatory task and stick to it. This can be as simple as deliberately maintaining good posture or using your nondominant hand to eat. The key element is to exercise your self-discipline. You don’t need to start big, just be consistent and mindful of your focus. Over time, you will be strengthening your “willpower muscle.”

- Sleep and rest also help to restore the ability to self-regulate. If you seem to be at the end of your rope, unable to cope and unwilling to do the next task, first ask yourself if you are getting enough sleep. Seven or eight hours of sleep is important for most of us to function well.

- A corollary to sleep and rest is that self-regulation later in the day is less effective. Be as strategic as possible, and don’t look to exercise feats of willpower later in the day. (Rachel may have to rethink the timing of her workout or use alternative strategies, suggested below, to help her get off the couch when she is already “running on empty.”)

- A boost of positive emotion has been shown to eliminate self-regulatory impairment. Find things, people, or events that make you feel good to replenish your willpower strength.

- Implementation intentions can be added to this list of willpower boosters. Make an implementation intention as a plan for action. As you know, this takes a specific form: “In situation X, I will do behavior Y to achieve my goal Z”; or “If this happens, then I’ll do this” (anticipating possible obstacles to your goal pursuit). The effect of these intentions is to put the stimulus for action into the environment and make the control of behavior a nonconscious process. A couple of studies have demonstrated that the automatic nature of the effects of implementation intentions counters the effects of self-regulatory depletion. Let’s take the example where research participants had to control their emotions during a humorous movie (suppressing their laughter). As you will recall, they are usually less capable of doing a subsequent experimental task that requires self-regulatory strength, such as solving a series of anagrams. However, for participants randomly assigned to an “if . . . then” implementation intention manipulation, who prepared by saying to themselves, “If I solve an anagram, then I will immediately start to work on the next one,” this depletion effect was eliminated (they solved as many anagrams as the group who were not depleted beforehand). This is an interesting result with clear implications for how we can strengthen our flagging willpower at the end of a long day. An implementation intention may well be the thing that gets you to exercise in the evening, even though you usually feel much too tired to begin. Note: This research underscores my focus on just get started. I think Rachel might be more successful with her evening exercise if she had the implementation intention of “If the kids are in bed, then I will go directly to the treadmill.” Once she starts, she might discover that she has the motivation and energy that she needs.

- Self-regulation appears to depend on available blood glucose. In some studies, even a single act of self-regulation has been shown to reduce the amount of available glucose in the bloodstream, impairing later self-regulatory attempts. Interestingly, just a drink of sugar-sweetened lemonade eliminated this self-regulatory depletion in experiments. Even though this research hasn’t always been replicated, the message is clear: Don’t get hypoglycemic; your self-regulation will suffer. Keep a piece of fruit (complex carbohydrate) handy to restore blood glucose.

- Be aware that social situations can require more self-regulation and effort than you may think. For example, if you are typically an introverted person but you have to act extraverted, or you have to suppress your desired reaction (scream at your boss) in favor of what is deemed more socially acceptable (acquiesce again to unreasonable demands), you will deplete your willpower for subsequent action. These social interactions may even make it more likely that you will say or do something you will regret in subsequent interactions. Getting along with others requires self-regulation, so you will need to think about points 1–6 to be best prepared to deal with demanding social situations.

- Finally, so much of our ability to self-regulate depends on our motivation. Even on an empty stomach, exhausted from not enough sleep and pushed to the limit for self-regulation, we can muster the willpower to continue to act appropriately. It is difficult, but it can be done, particularly if we focus on our values and goals to keep perspective on more than just the present moment. In doing this, we can transcend the immediate (and temporary) feelings we are having to keep from giving in to feel good, which lies at the heart of so much self-regulatory failure.