2

Is Procrastination Really a Problem? What Are the Costs of Procrastinating?

Procrastination is failing to get on with life itself.

I ATTENDED A CONFERENCE a few summers ago titled Living Well and Dying Well: New Frontiers of Positive Psychology, Therapy, and Spiritual Care. During a discussion of coping with death and counseling individuals who are grieving, one of the psychologists in attendance noted two kinds of regrets that people express in their grief over the loss of a loved one: regrets of commission and omission. The second regret, the things we omitted doing while our loved one was alive, captured my interest. Regrets of omission are so often the result of procrastination.

I asked this psychologist, “What is the nature of these regrets of omission?” adding, “Are these:

- Things people really intended to do but never did (i.e., procrastination)?

- Generalized possibilities of what they could have done?

- Cultural scripts of what they think they should have done, what would have been nice to do?

- Internalized expectations about what the loved one might have wanted them to do?”

The psychologist replied that all four types were part of the regrets he had seen in his practice.

So I pushed on a little further and asked which type of regret seemed most problematic. As I expected, given the guilt associated with procrastination, regret over the things these grieving people really intended to do but did not was most problematic. The regrets of omission related to our procrastination were most troubling in the grieving process.

Issue

Everyone procrastinates. I believe this, and research has documented this in a number of different ways. In fact, I think that people who say that they have never procrastinated might also say that they have never told a lie or been rude to someone. It is possible, I guess, but unlikely. We certainly do not like to admit to these undesirable actions.

So, if everyone procrastinates, why is it a problem?

The research evidence is clear. People who score high on self-report measures of procrastination also self-report lower achievement overall, more negative feelings, and even significantly more health problems. Let me discuss each of these briefly.

The lower achievement is easy to explain. Although we can all remember instances where we procrastinated and did very well (we cherish these memories to make us feel better and to justify even more procrastination), on the whole, procrastination results in less time to do a thorough job. This usually means poorer work overall. A meta-analysis of the procrastination research conducted by Piers Steel (University of Calgary) has shown that procrastination is certainly never helpful and usually harmful to our task performance.

The fact that procrastination is associated with more negative emotions (or moods) is puzzling. If we are procrastinating, you would think we would actually feel better because we are not doing the tasks we do not want to do in favor of things we enjoy. At least that is what you would think we are doing.

The thing is, our research shows that even when we are procrastinating, and I mean when we are actually off task and researchers ask us questions then about our feelings, we do not report feeling happier necessarily. There is a mixture of feelings experienced, including guilt. So, on the whole, procrastination does not make us feel that great, and this is particularly true in the long run.

Finally, the new research by Fuschia Sirois (Bishops University, Sherbrooke, Quebec) that demonstrates that procrastination actually compromises our health is very interesting. Procrastination seems to affect health in two ways. First, procrastination causes stress, which is not a good thing for our health for many reasons (e.g., stress compromises our immune systems).

Second, chronic procrastinators needlessly delay health behaviors such as exercising, eating healthfully, and getting enough sleep. This affects our health negatively, particularly over time. Sure, not exercising today or not eating vegetables today is not going to harm us today. But you know how it goes: Tomorrow is the same situation, we rationalize one more day of delay, and before we know it, it has been years of neglected (procrastinated) health behaviors. The results can be devastating, with increased risk for heart disease, diabetes, and other debilitating illnesses that can be prevented with more daily attention to simple but avoided health behaviors.

The day-to-day delay on small but cumulatively important tasks affects us in other ways as well. A good example is retirement savings. It is easy to put off saving to another day, but this procrastination costs us in the long run.

All of this is true about procrastination—it is seldom helpful (but we certainly recall when it is), and it is usually harmful to our task performance, psychological well-being, and even our physical health. Although all of these outcomes are negative, this is not what might concern us most about the consequences of procrastination.

Procrastination is a problem with not getting on with life itself. When we procrastinate on our goals, we are our own worst enemy. These are our goals, our tasks, and we are needlessly putting them off. Our goals are the things that make up a good portion of our lives. In fact, both philosophers and psychologists have proposed that happiness is found in the pursuit of our goals. It is not necessarily that we are accomplishing anything in particular, but that we are engaged in the pursuit of what we think is meaningful in our lives.

When we procrastinate on our goals, we are basically putting off our lives. We are certainly wasting the time we could be using toward our goal pursuit. The thing is, the most finite, limited resource in our lives is time. We only have a finite amount of time to live. Why waste it? Why waste it running away from tasks that we want or need to do?

Let’s return for a moment to the story I told at the beginning of this chapter. As I listened to psychologists present their research papers and therapists talk about the grieving process, I left each session more convinced of the importance of dealing with procrastination as a symptom of an existential malaise, a malaise that can only be addressed by our deep commitment to authoring the stories of our lives.

To author our own lives, we have to be an active agent in our lives, not a passive participant making excuses for what we are not doing. When we learn to stop needless, voluntary delay in our lives, we live more fully.

It is time to make a commitment to engaging in your life, achieving your goals, and enjoying the journey. Time is too precious to waste.

STRATEGY FOR CHANGE

One of the most important preconditions for successful change is a deep commitment to that change. You really have to value that change. So I want to focus your attention on the costs of your procrastination to enhance your goal commitment.

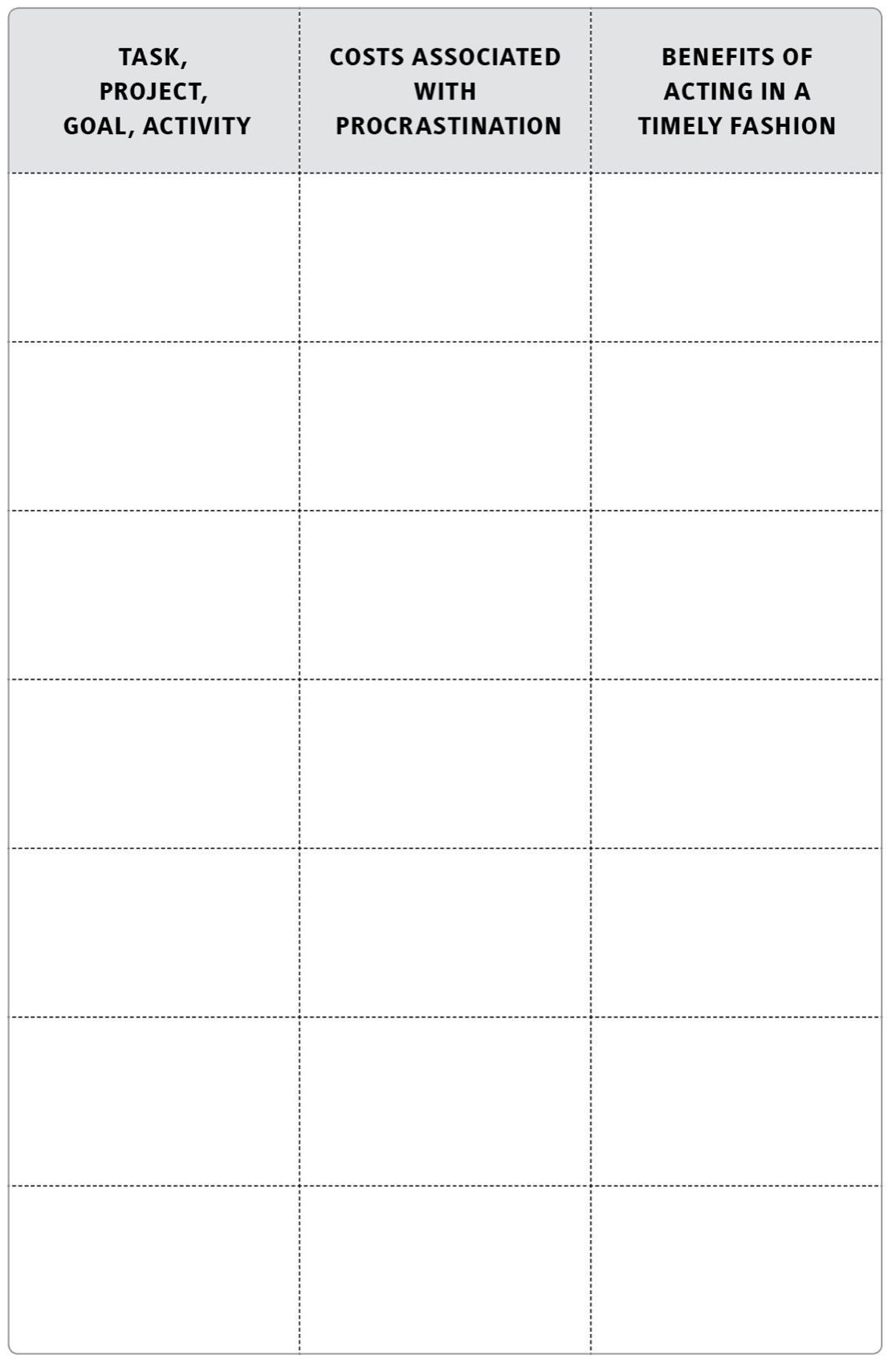

Take a moment now to think about the list of tasks that you came up with at the end of Chapter 1. Recall that these were the tasks (goals, projects) on which you are procrastinating. I have provided a table below into which you may want to copy this list of tasks (or goals) in the first column. You may want to add new ones, too, after reading this chapter and thinking further about procrastination. I do realize that every reader is different and that you may not want to write this out. If not, stick with this as a thought experiment and just think through the next little bit.

Next to each of these tasks or goals, note how your procrastination has affected you in terms of things such as your happiness, stress, health, finances, relationships, and so on. You may even want to discuss this with a confidante or a significant other in your life who knows you well. In fact, you may be surprised by what they may have to say about the costs of procrastination in your life. Like tobacco smoke, there are secondhand effects of procrastination of which you may be unaware, including broken promises, unfulfilled obligations, and the added burden to others of “picking up the pieces” while you are busy with your last-minute efforts . . . again.

In short, it is important to recognize and acknowledge all of the costs associated with the self-regulation failure we commonly call procrastination. This knowledge can be helpful in maintaining your commitment to change.

What I expect you will see in this list is how much you are paying for your procrastination. The reward of following through with your reading today is to learn how to eliminate these unnecessary costs in your life.

Strengthening Goal Intentions

It is one thing to know the cost of not acting; it is quite another to have a strong commitment to the goal itself. A strong goal intention, an intention for which you have a very strong commitment, is absolutely essential. As is commonly said, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

To strengthen a goal intention, it is important to recognize the benefits of acting now, not just the costs of needless delay. Taking time to think about how your goals align with your values and larger, longer-term life goals, or simply the short-term benefit of getting a necessary task done, can be an important step in strengthening goal intentions. The last column of the table provides space for this reflection. Add notes about why this goal or task is important to get done, as well as the benefits of acting now as opposed to later.

Finally, knowing something is different from realizing it—making it real—in our lives. For example, we can understand that health habits such as regular exercise or eating low-fat foods and less refined sugar are good for us. However, we can fail to act on this knowledge until something makes this information real in our lives. A common example of this is the strengthening of goal intentions for health behaviors following the diagnosis of a serious illness such as cardiovascular disease. With the diagnosis, the knowledge of the link between behavior and health outcomes becomes real in our lives, not just knowledge about the world in general.

The trouble is, it can be too late to act at this point, and waiting for an epiphany of this sort is not the most effective life strategy. It is very important to regularly examine our intentions as a starting point to reducing procrastination. To the extent that we can strengthen our goal intentions, we are much more likely to act in a timely manner.