1.

WE MUST PREPARE FOR A LONG WAR

On February 10, 1861, Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina, were taking rose cuttings in their garden at Brierfield, the Davis plantation on the rich bottomland along a looping bend in the Mississippi River. Three weeks earlier, just recovered from an illness that had kept him in bed for several days, Davis had resigned his seat in the United States Senate when he received official word of Mississippi’s secession from the Union. He and his family had made their way home slowly, stopping on January 28 at the state capital in Jackson, where Davis learned that he had been named major general of the Army of Mississippi. It was a position congenial to his desires. As a graduate of West Point, an officer in the regular army for seven years, commander of a volunteer regiment in the Mexican-American War, secretary of war in the Franklin Pierce administration, and chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Davis had vast and varied military experience qualifying him for such a position. He immediately set to work to reorganize and expand the state militia to meet a potential invasion threat from the United States Army. Davis also anticipated the possibility that the convention of delegates from six seceded states meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, might choose him as general-in-chief of the soon-to-be-created army of the Confederate States of America. But for now he was careworn and exhausted. He wanted only to get home to restore his health and energy, supervise his 113 slaves as they prepared Brierfield for the year’s cotton planting, and relax by working in his flower and vegetable gardens.

While Jefferson and Varina were taking rose cuttings that pleasant February day, a special messenger arrived from Vicksburg. He handed Davis a telegram. Varina watched her husband as he opened and read it. His face blanched, she recalled. “After a few minutes painful silence” he told her, “as a man might speak of a sentence of death,” that the convention at Montgomery had unanimously elected him provisional president of the Confederacy—not general-in-chief but commander in chief with all of its political as well as military responsibilities and vexations. He did not want the job. He had expected it to go to Howell Cobb of Georgia. But the convention, anticipating the possibility of war with the United States, had chosen Davis in considerable part because of his military qualifications, which none of the other leading candidates (including Cobb) possessed. Despite his misgivings, Davis’s strong sense of duty compelled him to accept the call. He prepared to leave for Montgomery the next day.1

Varina Davis

On his way to the Confederate capital, Davis gave twenty-five whistle-stop speeches. While he publicly expressed hopes that his new government would remain at peace with the United States, he told Governor Francis Pickens of South Carolina that he believed “a peaceful solution of our difficulties was not to be anticipated, and therefore my thoughts have been directed to the manner of rendering force effective.”2 One such means was to threaten the North with invasion if it dared to make war on the Confederacy. “There will be no war in our territory,” he told a cheering crowd in Jackson, Mississippi, on February 12. “It will be carried into the enemy’s territory.” At Stevenson, Alabama, two days later, Davis vowed to extend war “where food for the sword and torch await the armies. . . . Grass will grow in the northern cities where pavements have been worn off by the tread of commerce.”3 When he arrived at the railroad station in Montgomery on February 16, he pledged to the waiting crowd that if the North tried to coerce the Confederate states back into the Union, the Confederates would make the Northerners “smell Southern powder and feel Southern steel.” More soberly, in his brief inaugural address on February 18, Davis referred five times to the possibility of war and the need to create an army and a navy to meet the challenge. If “passion or lust for dominion” should cause the United States to wage war on the Confederacy, “we must prepare to meet the emergency and maintain, by the final arbitrament of the sword, the position which we have assumed among the nations of the earth.”4

Davis and the convention delegates, who reconstituted themselves as a provisional Congress, suited action to words. On February 26 the new president signed a law creating the infrastructure of a Confederate army: Ordnance, Quartermaster, Medical, and other staff departments modeled on those of the regular United States Army, with which Davis was familiar from his years as secretary of war. Subsequent legislation provided for the enlistment of volunteers to serve one year in the provisional army. They were to be organized into regiments by states, with company and sometimes regimental officers elected by the men and appointed by governors. Brigadier generals would be appointed by the president. Under this legislation a small army and even a navy began to take shape.

In this process Davis played a hands-on role, with every aspect of military organization passing across his desk and receiving his approval or disapproval. At this stage of his tenure as commander in chief, such micromanagement was a virtue because the Confederacy was inventing itself from scratch and Davis knew more about organizing and administering an army than any other Southerner. It was also a necessity because his initial choice as secretary of war, Leroy P. Walker of Alabama, was a poor administrator and was soon overwhelmed by the task. Davis had selected him mainly for reasons of political geography: Each of his six cabinet members came from one of the original seven Confederate states (including Texas when it soon joined the Confederacy), with Davis himself from the seventh. The president assigned Florida’s cabinet post to Stephen R. Mallory as secretary of the navy. Mallory turned out to be an excellent choice, for he created a navy out of virtually nothing. Under his leadership it pioneered in such technological innovations as ironclads, torpedoes (mines), and even a primitive submarine.

Armed forces need not only men; they also need arms and ammunition, shoes and clothing, all the accoutrements of soldiers and the capacity to transport them where needed to sustain hundreds of thousands of men who are removed from the production and transport of this matériel by their presence in the armed forces. Slavery gave the Confederacy one advantage in this respect: The slaves constituted a large percentage of the labor force in the Confederate states, and by staying on the job they freed white men for the army. But the slaves worked mainly in agriculture growing cotton and other staple crops primarily for export. In the production of the potential matériel of war, the seven Confederate states began life at a huge disadvantage. Even with the secession of four more slave states after the firing on Fort Sumter (to be discussed below), the Confederacy would possess only 12 percent as much industrial capacity as the Union states. In certain industries vital to military production, Northern superiority was even more decisive. According to the 1860 census, Union states had eleven times as many ships and boats as the Confederacy and produced fifteen times as much iron, seventeen times as many textile goods, twenty-four times as many locomotives, and thirty-two times as many firearms. The Union had more than twice the density of railroad mileage per square mile and several times the amount of rolling stock.

From his experience as secretary of war and chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs in the 1850s, Davis was acutely aware of these statistics. He also knew that the state arsenals seized by Southern militias contained mostly old and out-of-repair weapons. Despite his boast that Confederates would make Northerners smell Southern powder and feel Southern steel if they tried to subjugate the Confederacy, Davis knew that he had little powder and less steel. Three days after his inauguration as Confederate president, he sent Raphael Semmes of Alabama to the North to buy weapons and arms-making machinery.5 A veteran of almost thirty years in the United States Navy who would soon become the Confederacy’s most dashing sea captain, Semmes also proved adept at this initial assignment that Davis gave him. But the onset of war two months later soon overwhelmed the limited matériel that Semmes was able to acquire. For the first year of the war—and often thereafter—Davis’s strategic options as commander in chief would be severely constrained by persistent deficiencies in arms, accoutrements, transportation, and industrial capacity. Fast steamships carrying war matériel and trying to evade the ever-tightening Union blockade, and a crash program to build up war industries in the South, would only partly remedy these deficiencies.

• • •

WHILE SEMMES WAS IN THE NORTH BUYING ARMS, DAVIS was confronting his first crucial decision as commander in chief: what to do about the two principal forts in Confederate harbors still held by soldiers of the United States Army. When South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, the commander of the army garrison at Fort Moultrie, Maj. Robert Anderson, grew apprehensive that the hotheaded Charleston militia would attack this obsolete fort. On the night of December 26, Anderson secretly moved the garrison to the uncompleted but immensely strong Fort Sumter on an artificial island at the entrance to the harbor. The outraged Carolinians denounced this movement as a violation of their sovereignty, and sent commissioners to President James Buchanan in Washington to demand that the fort be turned over to the state. The previously pliable Buchanan surprised them by saying no. His administration even sent an unarmed merchant steamer, the Star of the West, with reinforcements for Fort Sumter, but it was turned back by South Carolina artillery.

Meanwhile, when Florida seceded in January her militia seized two outdated forts on the mainland at Pensacola. But the stronger Fort Pickens on Santa Rosa Island controlling the entrance to the harbor remained in Union hands. Tense standoffs at both Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens had persisted for several weeks when the Confederate government organized itself and Davis became president in February. The Congress in Montgomery instructed him to obtain control of these forts by negotiations if possible or by force if necessary. Davis sent commissioners to Washington to negotiate. He also named Pierre G. T. Beauregard and Braxton Bragg as the Confederacy’s first two brigadier generals and sent them to Charleston and Pensacola to take over the state militias, absorb them into the new Confederate army, and prepare to attack the forts if required.6

Montgomery, Alabama: The first capital of the Confederacy

The incoming Lincoln administration refused to meet officially with the Confederate commissioners. But Secretary of State William H. Seward, who expected to be the “premier” of the administration, informed them through an intermediary that he was working to get the troops removed from Fort Sumter in the interest of preserving peace. Seward hoped that such a gesture of conciliation might be a first step in a gradual process of wooing the seceded states back into the Union. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott of the United States Army supported Seward’s position, as did a majority of Lincoln’s cabinet at first.

Jefferson Davis would have been quite happy if Seward had succeeded in his efforts to get the garrison out of Sumter. But he repudiated any notion that this gesture might lead to reunion; on the contrary, he would have seen it as a recognition of Confederate sovereignty. That is how Abraham Lincoln saw it too. Fort Sumter had become the symbol of competing claims of sovereignty. So long as the American flag flew over the fort, the Confederate claim to be an independent nation was invalid. The same was true of Fort Pickens, and Davis instructed General Bragg to prepare to attack it if and when an actual attack order came.7

But no such order ever went to Bragg. The standoff at Sumter eclipsed the situation at Pensacola in the eyes of both Northerners and Southerners. When Lincoln informed South Carolina governor Francis Pickens of his intent to resupply the garrison at Fort Sumter, he forced Davis’s hand. If the Confederates allowed the supplies to go in, they would lose face in this symbolic battle of sovereignties. If they fired on the relief boats or on the fort, they would stand convicted of starting a war, thereby uniting a divided North. But Davis had reason to believe that an actual shooting war would bring more slave states into the Confederacy to stand with their Southern brethren against Yankee “coercion.” In any case, he was convinced that he could not yield his demand for the surrender of Fort Sumter without in effect yielding the Confederate claim to nationhood. At a tense meeting of the Confederate cabinet on April 8, a majority (evidently excepting only Secretary of State Robert Toombs) agreed with Davis. From Montgomery went a telegram to General Beauregard: Demand the evacuation of Sumter, and if it was refused, open fire. Beauregard sent his ultimatum; it was rejected; Confederate guns began shooting at 4:30 A.M. on April 12; the American flag was lowered in surrender two days later; and the war came.8

Lincoln’s call for troops to suppress a rebellion prompted four more slave states, led by Virginia, to join the Confederacy. Neither Lincoln nor Davis could foresee the huge and destructive scale of the war that ensued. But neither shared the opinions widespread among their respective publics that it would be a short war and an easy victory for their own side. “The people here are all in fine spirits,” wrote the wife of a Texas member of the provisional Congress two weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter. “No one doubts our success.”9 Davis tried to discourage such optimism. “We must prepare for a long war” and perhaps “unmerciful reverses at first,” he said to one overconfident friend. Davis scotched the notion that one Southerner could lick three Yankees. “Only fools doubted the courage of the Yankees to fight,” he declared, “and now we have stung their pride—we have roused them till they will fight like devils.”10

The original bill in Congress to create a Confederate army had authorized enlistments for six months. Davis had objected, insisting that it took at least that long to train a soldier, and urged a three-year term. Congress balked, and they finally compromised on one year. After Fort Sumter, Davis pressed Congress to enlarge the army and to require three-year terms for new recruits. As administered, this law allowed enlistees who supplied their own arms and equipment to sign up for one year; those who were equipped by the government would serve three years.11

As this recruitment policy suggests, a shortage of weapons and accoutrements plagued the rapidly growing Confederate army in 1861. The capture of the Norfolk navy yard on April 20 provided a windfall of 1,200 cannon, many of which were soon on their way to the dozens of forts already existing or under construction across the South. The army also could obtain plenty of horses and mules for transportation. Effective small arms and field artillery, however, were in woefully short supply. By July 1 the Confederacy had at least one hundred thousand men in its armies, many of them armed with shotguns and squirrel rifles. The War Department could have accepted thousands more had it been able to equip them.

What were these soldiers expected to do? In his message on April 29 to a special session of the provisional Congress, Davis said no more about carrying the war into the North. Instead, he announced a defensive national strategy: “We seek no conquest, no aggrandizement, no concession of any kind from the States with which we were lately confederated; all we ask is to be let alone.” But if the United States “attempt our subjugation by arms . . . we will . . . resist to the direst extremity.”12

Davis’s pledge to seek no conquest was somewhat disingenuous. He meant no aggrandizement or conquest of free states. Four border slave states had not seceded. Davis hoped that at least three of them—Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri—would join the Confederacy. And when it became possible, he was prepared to invade them to make it happen. As early as April 23 he approved the shipment of four pieces of artillery (in boxes labeled “marble”) to pro-Confederate governor Claiborne Jackson of Missouri to enable his secessionist militia to capture the St. Louis arsenal.13 That effort did not work out, but later in the summer Confederate troops invaded Missouri and occupied a substantial portion of Kentucky.

The Confederacy was a slaveholding republic. The defense of bondage from the perceived threat to its long-term survival by the election of Abraham Lincoln had been the avowed reason for secession. Davis made this point at considerable length in the same message to Congress in which he said that all the South wanted was to be let alone. In recent years, he declared, Republicans in the United States Congress had advocated “a persistent and organized system of hostile measures against the rights of the owners of slaves in the Southern States . . . for the purpose of rendering insecure the tenure of property in slaves . . . and reducing those States which held slaves to a condition of inferiority.” In 1860 a party came to power vowing “to legislate to the prejudice, detriment, or discouragement of the owners of that species of property” and to use “its power for the total exclusion of the slave States from all participation in the benefits of the public domain.” This policy would result in “annihilating in effect property worth thousands of millions of dollars” and “rendering the property in slaves so insecure as to be comparatively worthless.”14

One man whose property, Davis feared, might become comparatively worthless was Jefferson Davis. His 113 slaves were probably worth about $80,000 in 1860—the equivalent of several million dollars today. Another was his brother Joseph, twenty-four years older than Jefferson and something of a father figure who had helped Jefferson get his start as a planter twenty-five years earlier. Although the Davises were benign masters who treated their chattels with a degree of liberality, they were also proslavery partisans of the John C. Calhoun school. As a United States senator, Jefferson Davis had opposed the admission of California as a free state because he thought slavery could take root there. He wanted to annex Cuba in order to add a large new slave state to the Union. In an 1848 speech challenging antislavery senators, he declared that “if this is to be made the centre from which civil war is to radiate, here let the conflict begin.” During the election campaign of 1860, Davis told the people of Vicksburg that if an abolitionist president (Lincoln) was elected, he “would rather appeal to the God of Battles at once” and “welcome the invader to the harvest of death . . . than attempt to live longer in such a Union.”15

Davis’s conviction that slavery gave “the planting states” a “common interest of such magnitude” sustained his determination to eventually bring the border states into the Confederacy.16 But his first task was to devise a military strategy to defend the eleven states that constituted that entity in May 1861 from the buildup of Northern power to “subjugate” the South. Such a strategy would be grounded in an important reality, so obvious that its importance is often overlooked: The Confederacy began the war in firm military and political control of nearly all the territory in those eleven states. Such control is rarely the case in civil wars or revolutions, which typically require rebels or revolutionaries to fight to gain dominion over land or government or both. With a functioning government and an army already mobilized or mobilizing in May 1861, the Confederacy embraced more than 750,000 square miles in which not a single enemy soldier was to be found except at Fort Pickens and in Virginia at Fort Monroe and Alexandria across the Potomac River from Washington. All the Confederates had to do to “win” the war was to hold on to what they already had.

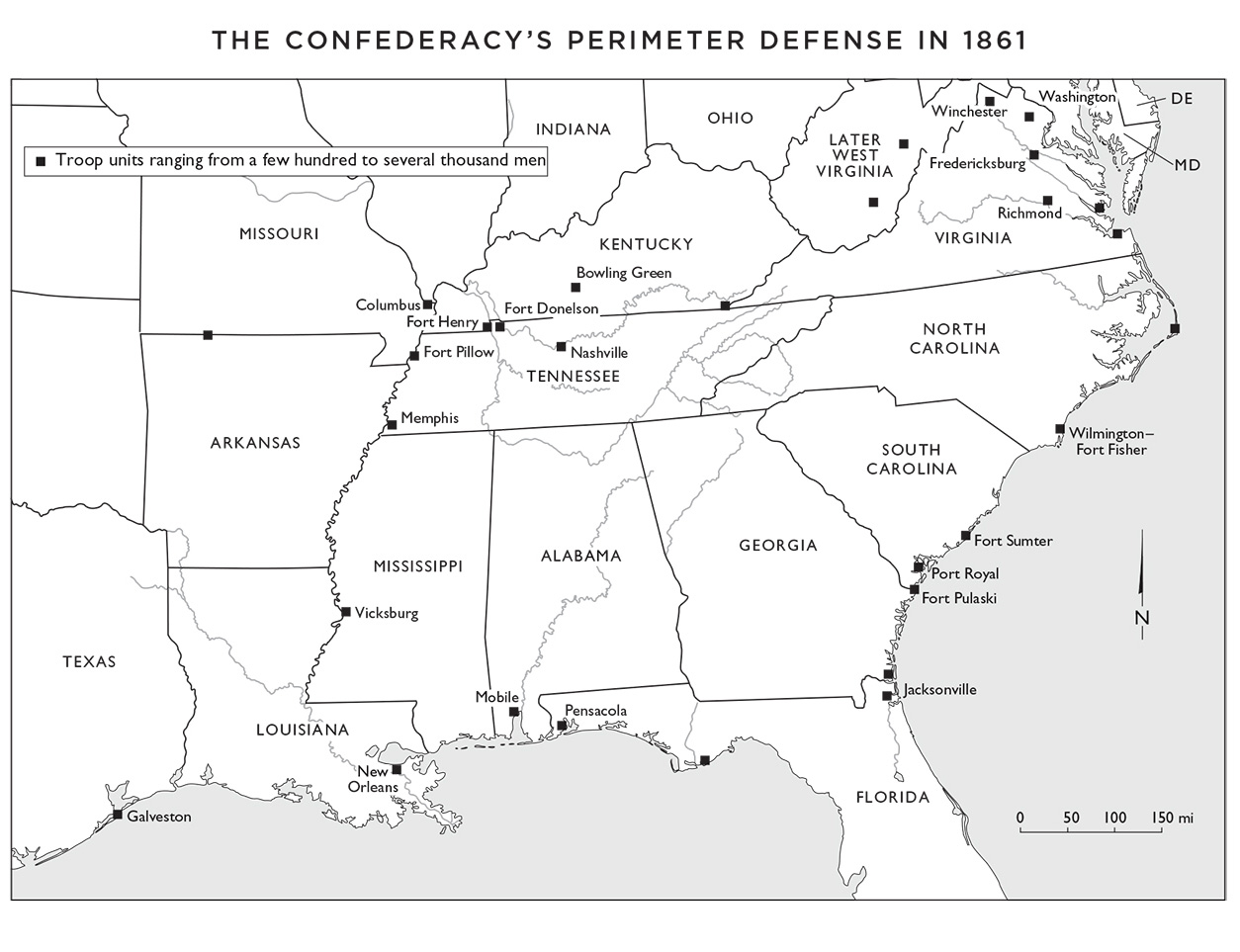

To accomplish that, Davis’s army was spread around the perimeter of those 750,000 square miles in numerous detachments guarding key strategic points—and some that were less strategic militarily but important politically. Historians have applied various labels to this strategy: perimeter defense; dispersed defense; cordon defense; extended defense. Many of these historians are critical of the strategy because it seemed to violate the principle of concentration of force. Dispersal created the possibility that the enemy, superior in numbers, might break through this thin gray line somewhere, cutting off and perhaps capturing one or more of these small armies and penetrating as far into Confederate territory as if it had been left undefended. Davis recognized this danger. He hoped partly to offset it by using the Confederacy’s advantage of interior lines to concentrate forces at the point of a major attack before the enemy could break through. Sometimes that worked, as in the case of the Battle of Manassas in July 1861; sometimes it did not, as in the cases of Union penetration at several locations in early 1862.

In any event, several considerations governed the adoption of the dispersed defense in 1861. The need to protect slavery seemed to require the defense of every foot of slave territory from the presence of Union soldiers, who would attract slaves from the surrounding countryside like a magnet. This attraction began at Fort Monroe in the first weeks of the war, and continued to escalate wherever Union armies set foot on Southern soil and Union navy ships moved up Southern rivers. Confederate diplomats hoped to achieve foreign recognition of their new nation, but to yield any part of it to enemy occupation in order to concentrate forces elsewhere might undermine that hope. The loss of territory also meant the loss of its resources and perhaps the desertion of soldiers from those areas. As Davis noted later in the war, “the general truth that power is increased by the concentration of an army is under our peculiar circumstances subject to modification. The evacuation of any portion of territory involves not only the loss of supplies but in every instance has been attended by a greater or less loss of troops.”17

The main reason for dispersal in 1861, however, was political—and politics was an essential part of national strategy. Southern states had seceded individually on the principle that the sovereignty of each state was superior to that of any other entity. The very name of the new nation, the Confederate States of America, implied an association of still-sovereign entities. This principle was recognized in the Confederate Constitution, which was ratified by “each State acting in its sovereign and independent character.” The governor of each state also insisted that its borders must be defended against invasion. If Davis had pursued a strategy of concentrating Confederate armies at two or three key points, leaving other areas open to enemy incursion, the political consequences could have been disastrous. Popular and political pressures therefore compelled him to scatter small armies around the perimeter at a couple of dozen places.

Davis’s correspondence reflected these pressures. As the Confederate government prepared to move from Montgomery to Richmond and soldiers from various states began to concentrate in Virginia, telegrams and letters of protest cascaded across the president’s desk. “The Gulf States expect your care, you were elected President of them, not of Virginia,” complained an Alabamian. From the prominent Mississippian Jacob Thompson came a report that “the fear [here] is that [the] eye of the Administration is so exclusively fixed upon [Virginia] that we may be neglected & stripped of the means of defence.” The Committee of Public Safety in Corpus Christi, Texas, pleaded for men and arms to repel a rumored Yankee invasion.18 The son-in-law of Davis’s brother Joseph wrote from his plantation in Louisiana that “there is great fear at present in this Country of an invasion down the river.” The governor of Louisiana echoed this fear, and asked also for greater attention to the defense of Bayou Atchafalaya and Bayou Teche. “Much uneasiness felt here in consequence of our condition,” declared the governor. “I am I may [say] constantly harassed on this subject. . . . Great opposition here to another man leaving the state, & I must say to a certain extent I participate in the feeling.” Claiming to apprehend an attack on the Georgia coast, Governor Joseph Brown of that state expressed reluctance to send any more Georgia troops “to go glory hunting in Virginia. . . . While I still recognize the authority of the President . . . I demand the exercise of that authority in behalf of the defenseless and unprotected citizens of the State.”19

Davis did his best to respond to those demands he considered reasonable, but there were not enough men and arms to satisfy all needs. To the governor of Tennessee he wrote that “your suggestion with regard to the distribution of the troops, in the several sections of Tennessee, is approved, and shall be observed, so far as possible.”20 Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, the senior commander in Virginia, lamented the shortages of men and weapons to defend western Virginia. The governor backed Johnston’s complaints. “I wish I could send additional force to occupy Loudon,” Davis told them, “but my means are short of the wants of each division of the wide frontier I am laboring to protect. . . . Our line of defence is a long one, and my duty embraces all its parts. . . . Missouri and Kentucky demand our attention, and the Southern coast needs additional defense.”21

• • •

IN MAY 1861 THE CONFEDERATE GOVERNMENT ACCEPTED an invitation from Virginia to transfer the capital to Richmond. The accommodations at Montgomery were woefully inadequate, and moving the capital to Virginia would cement the vital allegiance of that state to the Confederacy. This action ensured that the most crucial operations of the war were likely to take place between the two capitals only one hundred miles apart. It presented Davis with the delicate task of balancing the defense of points distant from Richmond with the preeminent need to protect the capital. When the governors of South Carolina and Georgia petitioned for the return of their states’ regiments from Virginia after the Union capture of the coastal islands of those states in the fall of 1861, Davis refused. “The threatening power before us [here] renders it out of the question that the troops specified should be withdrawn,” he wrote. Davis instructed Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin (who had replaced the hapless Leroy P. Walker) to reject the governors’ entreaties. Benjamin bluntly told Brown that it would be “suicidal to comply with your request.” Other governors were making similar demands, and if the administration gave in to Brown it would have to give in to all of them. Confederate forces could not be broken into fragments “at the request of each Governor who may be alarmed for the safety of his people.”22

The Confederate executive mansion in Richmond

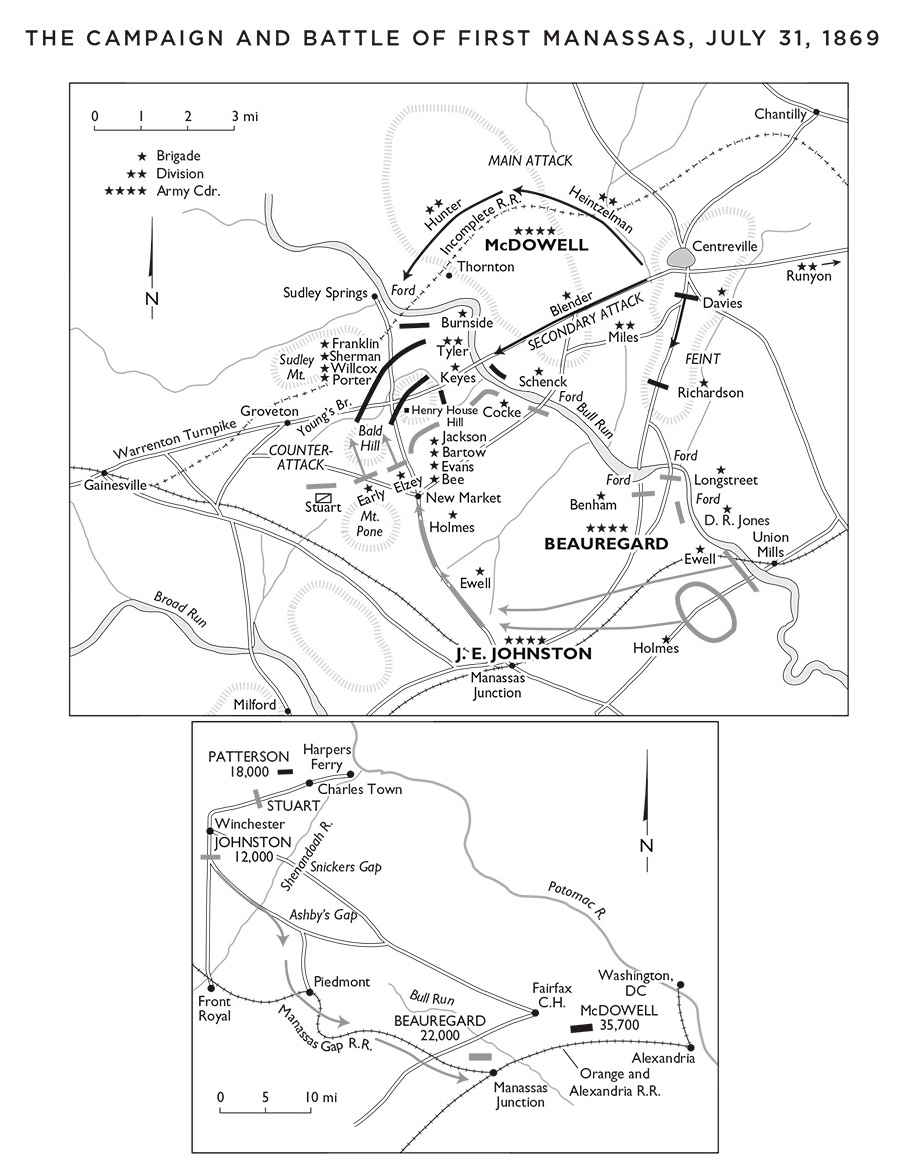

Both the Union and Confederate governments organized their largest armies under what they presumed to be their best commanders to attack or defend the new Confederate capital. Twenty thousand Confederate troops under General Beauregard were stationed at Manassas Junction protecting this key railroad connection with Richmond to the south and the Shenandoah Valley to the west, where General Joseph Johnston commanded another twelve thousand defending the valley. Each Confederate force confronted a larger Union army, but interior lines utilizing the rail connection gave Southern armies the ability to reinforce one another more quickly than their adversaries could combine. Beauregard proposed to use this advantage by having Johnston join him at Manassas for an offensive to recapture Alexandria, which the Federals had seized in May. Davis rejected this suggestion, which would have abandoned the Shenandoah Valley to the enemy, who could then use the same rail network to attack Johnston and Beauregard from the rear while they were battling the main Union army in their front.23

Undeterred, Beauregard came up with an even more ambitious and fanciful scheme in July. Johnston should join him to attack the Yankees near Alexandria, and after defeating them the combined armies should return quickly to the valley, whip the enemy there, then move farther west to defeat the Federals in the mountains of western Virginia, where they had gained control of Unionist counties in that region. After these lightning strikes, the victorious Confederates could cross the Potomac and attack Washington. The exuberant Beauregard sent an aide, James Chesnut (whose wife, Mary Boykin Chesnut, kept a diary that became a famous source for Confederate history), to Richmond to present this plan to Davis. The president rose from a sickbed to meet with Chesnut and with Adj. Gen. Samuel Cooper and Gen. Robert E. Lee, who was serving as a military adviser to Davis. They heard Chesnut out, and gently but firmly rejected the proposal, which they described as impressive on paper and brilliant in results “if we should meet with no disaster in details”—a kind way of saying that it bore no relationship to the real world of logistics, transportation, and enemy actions.24

Davis did hope that if the enemy gave him sufficient time, he could build up an army in Virginia strong enough “to be able to change from the defensive to an offensive attitude” and “achieve a victory alike glorious and beneficial,” to “drive the invader from Virginia & teach our insolent foe some lessons which will incline him to seek for a speedy peace.”25 These words offered a hint of what would become a hallmark of Davis’s preferred military strategy during the next two years. He later labeled it “offensive-defensive”—the best way to defend the Confederacy was to seize opportunities to take the offensive and force the enemy to sue for peace.

But in July 1861 the enemy did not give him time and opportunity. A few days after disapproving of Beauregard’s fantasy offensive, Davis learned of the Union army’s advance toward Manassas. He ordered Johnston to leave behind a small holding force in the valley and join Beauregard by rail with the rest of his troops. He also ordered Brig. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, commander of a contingent of three thousand men at Fredericksburg, to take them to Manassas.26 This concentration using interior lines was successful. These reinforcements arrived in time to enable Beauregard to hold off the attacks by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Federals along the sluggish stream of Bull Run on a brutally hot July 21. The last brigade of Johnston’s army, just off the train at Manassas in midafternoon, helped spearhead a counterattack that turned Union defeat into a rout.

One other reinforcement detrained at Manassas that afternoon: Jefferson Davis. Ever since the war began, many Southerners had expected Davis to take personal command of the principal army in the field. Davis himself sometimes intimated an intention to do so. His West Point training and experience as a combat commander in the Mexican-American War seemed to fit him for this role. One of the reasons for moving the capital to Richmond was the expectation that the commander in chief would be closer to the principal war theater and could take direct command.27 After a meeting with Davis in June, his good friend since West Point days, Leonidas Polk (whom Davis appointed as a major general to command in Tennessee), told his wife that “Davis will take the field in person when the movement is to be made.” Even Joseph E. Johnston urged the president to “appear in the position Genl. Washington occupied during the revolution. . . . Civil affairs can be postponed.”28

But even if civil affairs could be postponed, the multitude of tasks connected with organizing, arming, financing, and appointing commanders for armies scattered from Virginia to Texas required all of Davis’s time and energy—and then some. He insisted on reading and acting on all of the papers that crossed his desk. He put in twelve to fourteen hours a day. This hands-on activity as commander in chief at his desk (or sickbed) left him little opportunity for hands-on command in the field. Nevertheless, as the prospect of battle in northern Virginia approached, he grew restless in Richmond and chafed to join the army concentrating at Manassas. The Confederate Congress was scheduled to meet in Richmond on July 20, however, and he needed to remain there to address it.

On the warm Sunday morning of July 21 he could stand it no longer. He commandeered a special train and with a single aide he chugged northward more than a hundred slow, frustrating miles. Arriving at Manassas Junction in midafternoon, Davis borrowed a horse and rode toward the sound of the guns. He was dismayed by what he first encountered: stragglers and wounded men bearing tales of defeat, damaged equipment, the usual detritus in the rear of a battlefield. Davis tried to rally the stragglers. “I am President Davis,” he shouted. “Follow me back to the field.” Some did. By the time Davis reached Johnston’s headquarters, where he found the general sending reinforcements to the front, it was clear that the Confederates were victorious. Union troops were in headlong retreat. Davis rode farther forward and addressed the soldiers, who cheered him to the echo. It was perhaps his happiest moment in the war.29

Davis sent a jubilant telegram to Adjutant General Cooper in Richmond: “Our forces have won a glorious victory. The enemy was routed and fled precipitately.”30 Johnston and Beauregard may have raised their eyebrows at this. Was the president trying to take credit for what they had achieved before he arrived? In any event, the three men were cordial with one another at Johnston’s headquarters that evening. Davis wanted to organize a pursuit of the beaten enemy, and suggested that Beauregard or Johnston order such a movement. They remained silent, presumably because as commander in chief, Davis was now in charge. He began to dictate an order, but upon reflection and further consultation, he concluded that in the darkness and the disorganized confusion of even the triumphant Confederates, an effective pursuit was impossible. The next morning Beauregard ordered a reconnaissance forward, but heavy rain and empty haversacks with no immediate prospect of resupply brought the advance to a halt.31

In a private letter to Davis a few days later, General Johnston offered another reason for the army’s inability to press after the enemy. “This victory disorganized our volunteers as utterly as a defeat would do in an army of regulars,” Johnston reported. “Every body, officer and private, seemed to think he had fulfilled all his obligations to the country—& . . . it was his privilege to look after his friends, procure trophies, or amuse himself—It was several days after you left us [on July 23] before the regiments who had really fought could be reassembled. . . . This trait in the volunteer character gives us real anxiety.”32

The failure to follow up the victory at Manassas with an effective pursuit stored up controversy for the future. But Confederates everywhere basked in the immediate afterglow of the battle. Davis promoted Beauregard from brigadier to full general (Johnston already held that rank). Beauregard’s popularity, already great because of his capture of Fort Sumter, soared even higher. Davis returned to Richmond, and on the evening of July 23 he responded to the call of a large crowd outside his home for a speech. The diarist Mary Chesnut, a close friend of the president’s, was untypically critical of his address. He “took all the credit to himself for the victory,” she wrote. “Said the wounded roused & shouted for Jeff Davis—& the men rallied at the sight of him & rushed on & routed the enemy. The truth is Jeff Davis was not two miles from the battle-field—but he is greedy for military fame.”33

Beauregard no doubt learned of this speech from James Chesnut, who had been his aide at the battle. The general began complaining about the failure of Commissary General Lucius B. Northrop to keep his army supplied; some of the regiments were nearly starving, reported Beauregard with considerable exaggeration. Northrop was noted as an old friend of Davis’s from their army days together in the early 1830s, and Beauregard clearly intended his criticism of Northrop as an indictment of Davis’s poor judgment in appointing him commissary general. Beauregard also began hinting to friendly congressmen that this supply deficiency was the reason he could not follow up the victory at Manassas. “The want of food and transportation has made us lose all the fruits of our victory,” he told them. “From all accounts, Washington could have been taken up to the 24th instant, by twenty thousand men! Only think of the brilliant results we have lost by the two causes referred to!”34

A dispute over army command injected additional poison into the deteriorating relationship between Davis and Beauregard. The latter’s troops at Manassas (designated at the time as the Army of the Potomac—not to be confused with the Union army of the same name) had been merged with Johnston’s army from the Shenandoah Valley, with Johnston as commander by seniority of rank. But Beauregard insisted on issuing orders to his own half of the army as if it were a separate organization. The new secretary of war, Judah Benjamin, tried to set him straight. “You are second in command of the whole Army of the Potomac, and not first in command of half of the army.” Beauregard was infuriated by Benjamin’s lecturing style. He wrote to Davis asking him “as an educated soldier . . . to shield me from these ill-timed, unaccountable annoyances.” Davis was getting fed up with Beauregard’s complaints, and replied to him, “I do not feel competent to instruct Mr. Benjamin in the matter of style. . . . I cannot recognize the pretension . . . that your army and you are outside the limits of the law.”35

P. G. T. Beauregard

This caustic correspondence took place in the midst of another contretemps between Davis and Beauregard. The general did not submit his official report of the Battle of Manassas until mid-October. For some reason never explained, the War Department did not forward a copy to Davis, who read an account of it in the Richmond Dispatch. This version focused on Beauregard’s discussion of his plan for a multipronged offensive presented by James Chesnut to Davis and Lee a week before the battle, and their rejection of it. Beauregard implied that Davis had therefore prevented the glorious success that such an offensive was sure to have accomplished. Somehow the press accounts mixed up this issue with the question of why the army did not pursue the beaten Federals after Manassas. They concluded that Davis had restrained Beauregard (when the opposite was in fact the case). The president called for the actual report from the War Department. “With much surprise,” he wrote Beauregard, “I found that the newspaper statements were sustained by the text of your report.” The report itself, and especially its leak to the Dispatch, appeared to Davis like “an attempt to exalt yourself at my expense.”36 Indeed it was, and Davis never fully trusted Beauregard again. He also never fully put to rest the myth that he had prevented the Confederate army from capturing Washington in July 1861.37

This altercation with Beauregard was all the more painful for Davis because it came in the wake of a dispute with Joseph Johnston over his rank relative to other Confederate generals. In May 1861 the Confederate Congress had authorized the appointment of five full generals. The law specified that their rank would be equivalent to their relative grade in the United States Army in the same branch of the service before they had resigned to go south. Thus Davis gave the top ranking to Samuel Cooper as adjutant and inspector general, the same staff position he had held in the old army. Davis named his longtime friend Albert Sidney Johnston (who was on his way to Richmond from California) to the second position, followed by Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, and Pierre G. T. Beauregard. When Johnston learned in September of his number four grade, he exploded in anger. All along he had assumed that he was number one, based on his position as quartermaster general in the prewar army with the rank of brigadier general, while the three that Davis ranked above him had been colonels. Johnston sat down and wrote a blistering letter to Davis venting his outrage. The president’s action, Johnston told him, was a “studied indignity” that tarnished “my fair fame as a soldier and a man” and was “a blow aimed at me only,” especially since he was in command during the great victory at Manassas and those ranked above him had not “yet struck a blow for the Confederacy.”38

This missive reached Davis while he was suffering another attack of illness, a recurrence of his old malarial fever, which no doubt sharpened the asperity of his reply. He acknowledged receiving Johnston’s letter: “Its language is, as you say, unusual; its arguments and statements utterly one-sided; and its insinuations as unfounded as they are unbecoming.”39 That was it; no response to Johnston’s arguments, no explanation of the reason for the ranking. Johnston’s grade as a line officer in the old army was lieutenant colonel, while the three men ranked above him had been full colonels. His brigadier generalship was in a staff position, while his arm of service in the Confederacy was as a line officer, so under the terms of the law his prewar grade was below the others’. Even if Davis had bothered to explain all this to Johnston, the general would not have been satisfied. The insult to his honor, as he believed it to be, rankled him for the rest of his life. But he dropped the matter for now, and neither he nor Davis mentioned it to each other again.

After all, Davis and Johnston and Beauregard had a war to fight against the Yankees that was more important than a war among themselves. Their relations during strategy discussions that fall were professionally correct, if not warm. These discussions took place against the backdrop of a growing clamor from the press and public for an offensive. “The idea of waiting for blows, instead of striking them, is altogether unsuited to the genius of our people,” declared the Richmond Examiner. “The aggressive policy is the truly defensive one. A column pushed forward into Ohio or Pennsylvania is worth more to us, as a defensive measure, than a whole tier of seacoast batteries from Norfolk to the Rio Grande.”40

Davis agreed, for he too thought the best defense was a good offense. But he was also painfully aware of the shortages of arms and logistical capacity that precluded offensive operations in the fall of 1861. An anti-Davis faction centered on the Examiner and the Charleston Mercury began to form on this issue. The victory at Manassas, for which they credited Beauregard, convinced them that Confederate forces had the Yankees at their mercy and could go anywhere they liked. It was Davis, they charged, who held Beauregard back. “The continued attacks of the Mercury,” observed a South Carolina friend of the president’s, “are making something of a party against him. . . . The policy which prevents forward movements by our army does not meet the approval of this party, and they, far removed from the seat of the war and ignorant of what reasons prevent a forward movement, deem themselves far more competent to judge of what is proper to be done than those who, bearing the brunt and seeing everything, are.”41

Davis chafed at this censure. But “I have borne reproach in silence,” he explained privately, “because to reply by an exact statement of facts would have exposed our weakness to the enemy.” His critics, Davis added, “seem to have fallen into the not uncommon mistake of supposing that I have chosen to carry on the war upon a ‘purely defensive’ system.” Nothing could be more wrong; “the advantage of selecting the time and place of attack was too apparent to have been overlooked.” But there were not enough men and guns to take the offensive. “The country has supposed our armies more numerous than they were, and our munitions of war more extensive than they have been. . . . Without military stores, without the workshops to create them, without the power to import them, necessity not choice has compelled us to occupy strong positions and everywhere to confront the enemy without reserves.”42

On September 30, 1861, Davis traveled from Richmond to the Confederate front lines near Centreville to confer with Johnston, Beauregard, and Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith, a native Kentuckian who had recently committed to the Confederacy and was given a high position in the army. The four men met for several hours on October 1 to thrash out strategic options. The generals wanted to launch an offensive across the Potomac to flank Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Union Army of the Potomac out of its position at Alexandria and fight it in Maryland. Davis was all for the strategy. He had even brought maps of the Potomac fords. The president had been funneling newly organized regiments to the army; in the absence of strength reports from Johnston, he assumed that the army was substantially larger than it had been at Manassas. He was shocked to learn that, to the contrary, because of illness the number of effective troops was only about forty thousand.

Davis asked how many additional men would be necessary for the contemplated offensive. Another twenty thousand, the generals responded, and they must be well-trained troops, not raw recruits. Where would they come from? wondered the commander in chief as he reflected on his responsibility for the whole Confederacy, not just Virginia. From the southern Atlantic coast, from Pensacola, perhaps some from Tennessee, suggested Smith. “Can you not,” he asked, “by stripping other points to the last they will bear, and, even risking defeat at all other places, put us in a condition to move forward? Success here at this time saves everything; defeat here loses all.” No, he could not, answered Davis. He was already under fire from several governors for neglecting the defense of their states. To take more men from those states was impossible.43

The conference broke up on an unhappy note. There would be no Confederate offensive that fall. Nor would there be a Union offensive, for McClellan estimated Confederate strength at more than twice its actual numbers. Both armies went into winter quarters. And well before they emerged in the spring, the scene of action had shifted to the southern Atlantic coast and to the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in the West.