2.

WINTER OF DISCONTENT

Jefferson Davis was born in Kentucky and returned there twice to attend school at St. Thomas College and Transylvania University before going on to West Point. Like his fellow Kentucky native Abraham Lincoln, the Confederate president was acutely aware of the state’s strategic importance in the Civil War. Bordered by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, with the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers flowing through it, Kentucky was both a buffer between North and South and a route of invasion. Heir to the nationalism of Henry Clay, the state had a pro-Confederate governor in 1861, but a majority of its legislature was Unionist. Divided in the allegiances of its people, Kentucky declared its neutrality at the beginning of the war and sought to mediate between the two sides. Davis and Lincoln both decided to respect this neutrality and refrained from sending troops into the state, for it was clear that whichever side did so first would drive the state into the arms of the other.

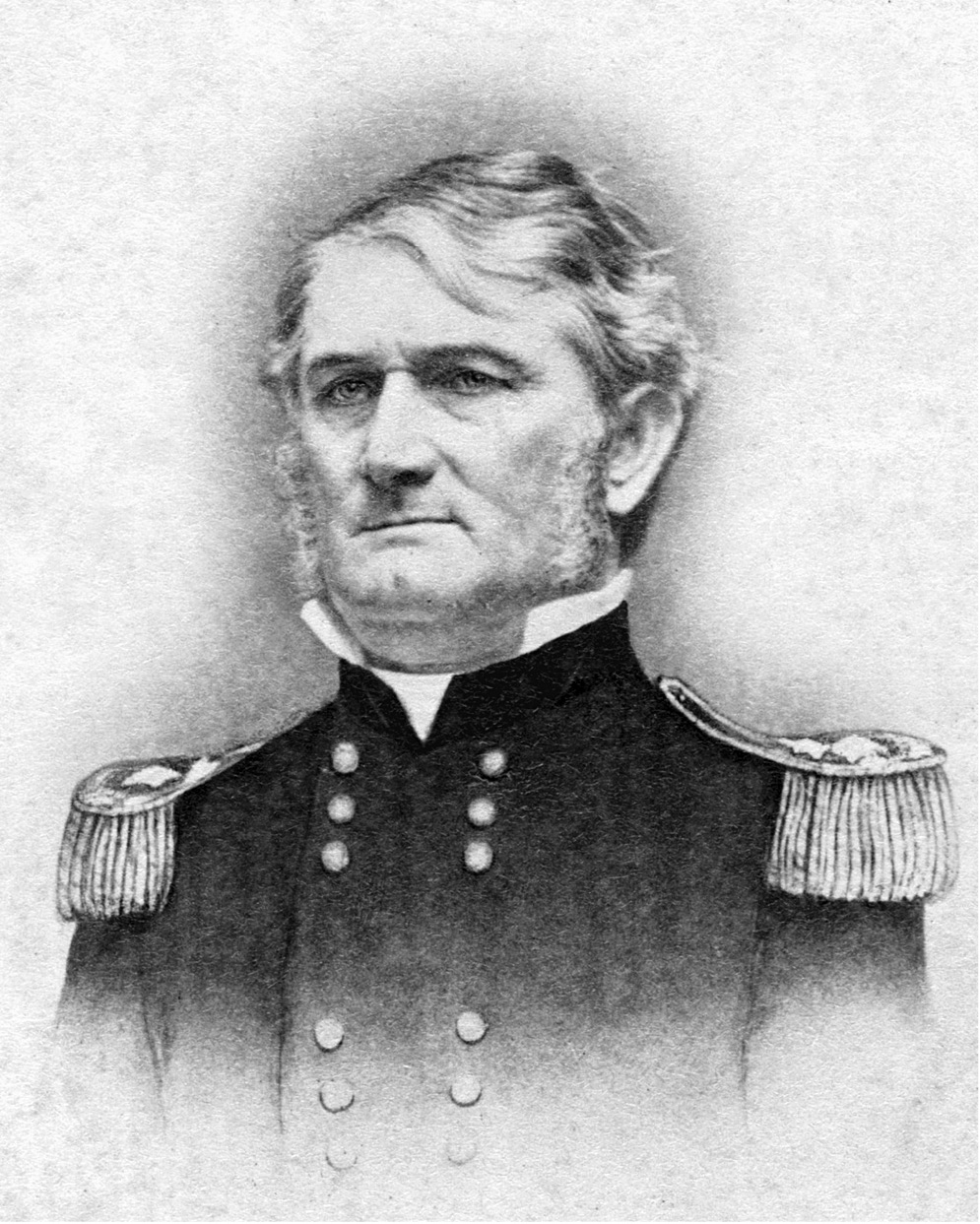

But pro-Confederate Kentuckians organized “state guard” regiments and Unionists formed “home guards.” They were armed with weapons smuggled into the state, whose neutrality was becoming increasingly fragile. Confederate troops in Tennessee near the Kentucky border were commanded by Davis’s longtime friend Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, who had left the United States Army after graduating from West Point to become an Episcopal priest and eventually a bishop. He donned a uniform again when the war began. Union troops at Cairo, Illinois, across the Ohio River from Kentucky, were commanded by Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Fearing that Grant intended to seize the strategic heights overlooking the Mississippi River at Columbus, Kentucky, Polk decided to act first. He occupied Columbus on September 3, 1861.

Leonidas Polk

Polk’s fears were well founded and his movement was militarily sound. But it was a political blunder. Kentucky’s legislature denounced the Confederate “invaders.” The governor of Tennessee immediately wired Davis that Polk’s action would “injure our cause” in Kentucky and urged the president to order Polk to withdraw his troops. Davis had the secretary of war send a withdrawal order, but this telegram crossed with one from Polk explaining the reasons for his action. In response, Davis became indecisive. He telegraphed Polk that “the necessity must justify the action,” by which he may have meant that Polk should provide a fuller explanation before receiving presidential approval. But Polk interpreted the message itself as approval. He replied that Davis’s telegram “gives great relief. The military necessity is fully verified and justified” by Grant’s subsequent occupation of Paducah and Smithland in Kentucky, where the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers flowed into the Ohio. Grant’s action, of course, came in response to Polk’s, and was endorsed by the Kentucky legislature. The governor of Tennessee continued to insist that the Confederate cause had suffered a setback in Kentucky, and most historians agree. But Davis came around to Polk’s position that military necessity trumped political considerations.1

On September 15 Davis sent General Albert Sidney Johnston to take charge in Kentucky. His command embraced the Confederacy’s largest military department, stretching from eastern Kentucky all the way across the Mississippi River to include Missouri and Arkansas. Confederate troops had invaded Missouri and had won the Battles of Wilson’s Creek in August and Lexington in September. Although the official state governments of both Kentucky and Missouri remained loyal to the Union, pro-Confederate minorities established their own governments and were admitted to full representation in the Confederate Congress. But Union forces retained military and political control of most of both states during most of the war.

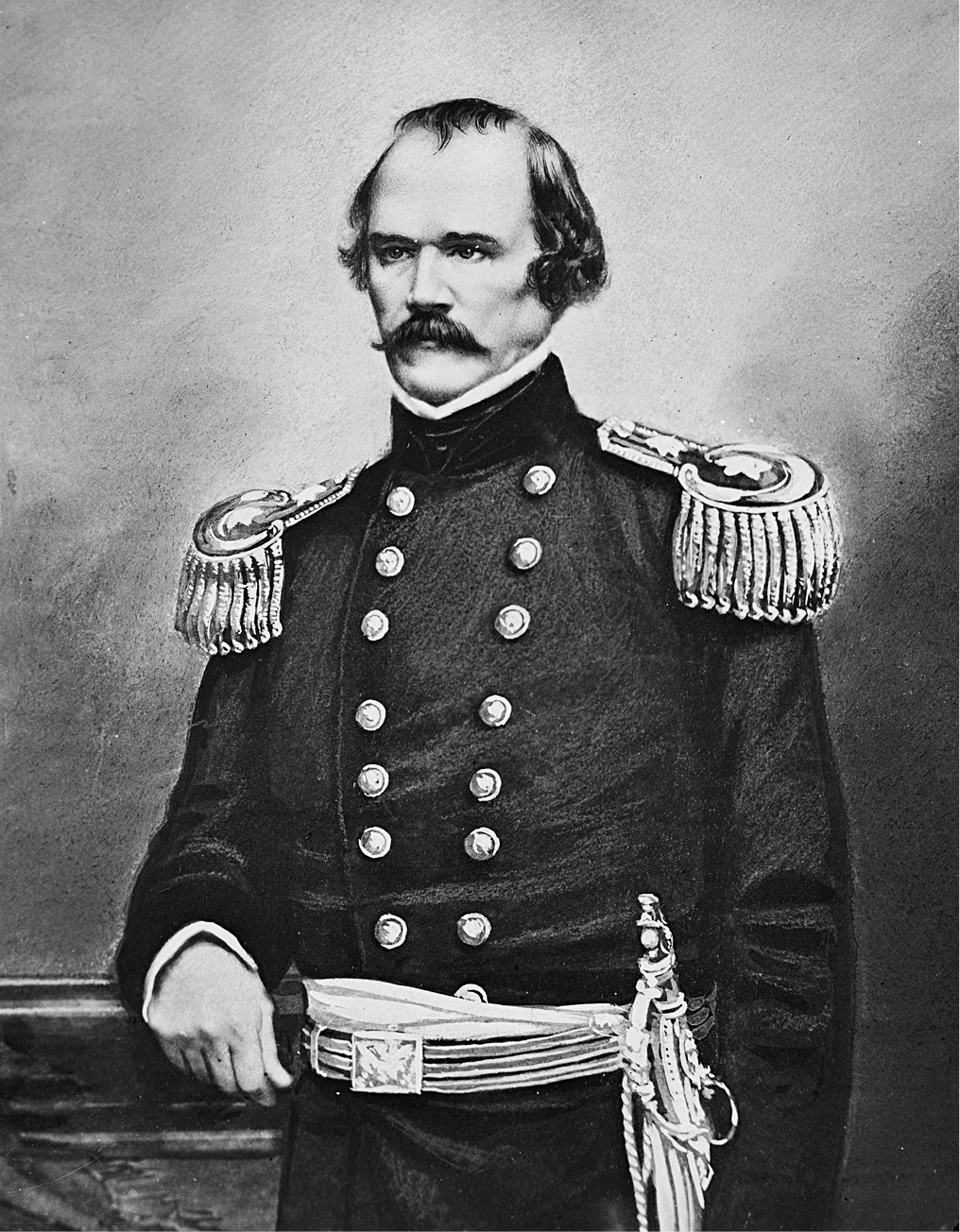

Five years older than Davis, Albert Sidney Johnston had been a mentor and friend when they both attended Transylvania University and the United States Military Academy in the 1820s. Johnston had remained Davis’s idol ever since. Also a native of Kentucky, Johnston had become an adoptive Texan, fought in that republic’s war of independence in 1836, and returned to the American army when Texas entered the Union. He was commanding the Department of the Pacific when the Civil War broke out. Johnston turned down a high command in the Union army, submitted his resignation, accepted a commission as the second-ranking full general in the Confederate army, made his way across the Southwest dodging Union patrols and Apache raiders, and in September arrived at Richmond, where Davis immediately assigned him to Kentucky.

Johnston made his headquarters at Bowling Green, from where he surveyed his huge department with despair. He had only forty thousand men to defend a line that stretched five hundred miles from the Cumberland Gap to southwest Missouri. Many of these men were raw recruits with inadequate arms and accoutrements. Johnston pleaded with Davis for reinforcements. In January 1862 he sent a staff officer to Richmond to appeal personally to Davis. The officer found the president “careworn and irritable” as he handed him a letter from Johnston suggesting that he strip other theaters to send men to Kentucky. “My God!” Davis exclaimed. “Why did General Johnston send you to me for arms and reinforcements, when he must know that I have neither. He has plenty of men in Tennessee, and they must have arms of some kind—shotguns, rifles, even pikes could be used.” By the next day Davis had calmed down, but he still instructed the officer: “Tell my friend, General Johnston, that I can do nothing for him; that he must rely on his own resources.”2

Although Johnston was short of men, he had plenty of ingenuity. He leaked disinformation that greatly puffed up the size of his army. These rumors and reports found their way into Union lines, where they were swallowed without skepticism. The Union commander in Kentucky, Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, expressed alarm at the reported buildup of Confederate forces. Sherman became so upset that the press began calling him insane, and he was replaced by Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell. Johnston managed gradually to increase his force and arm many of his men with better weapons than shotguns and pikes. He also received a significant reinforcement from Virginia: Pierre G. T. Beauregard, who had sought transfer from an unsatisfactory position as second in command to Joseph Johnston but was willing to accept the same position under Sidney Johnston. Davis was quite happy to see Beauregard leave Virginia.

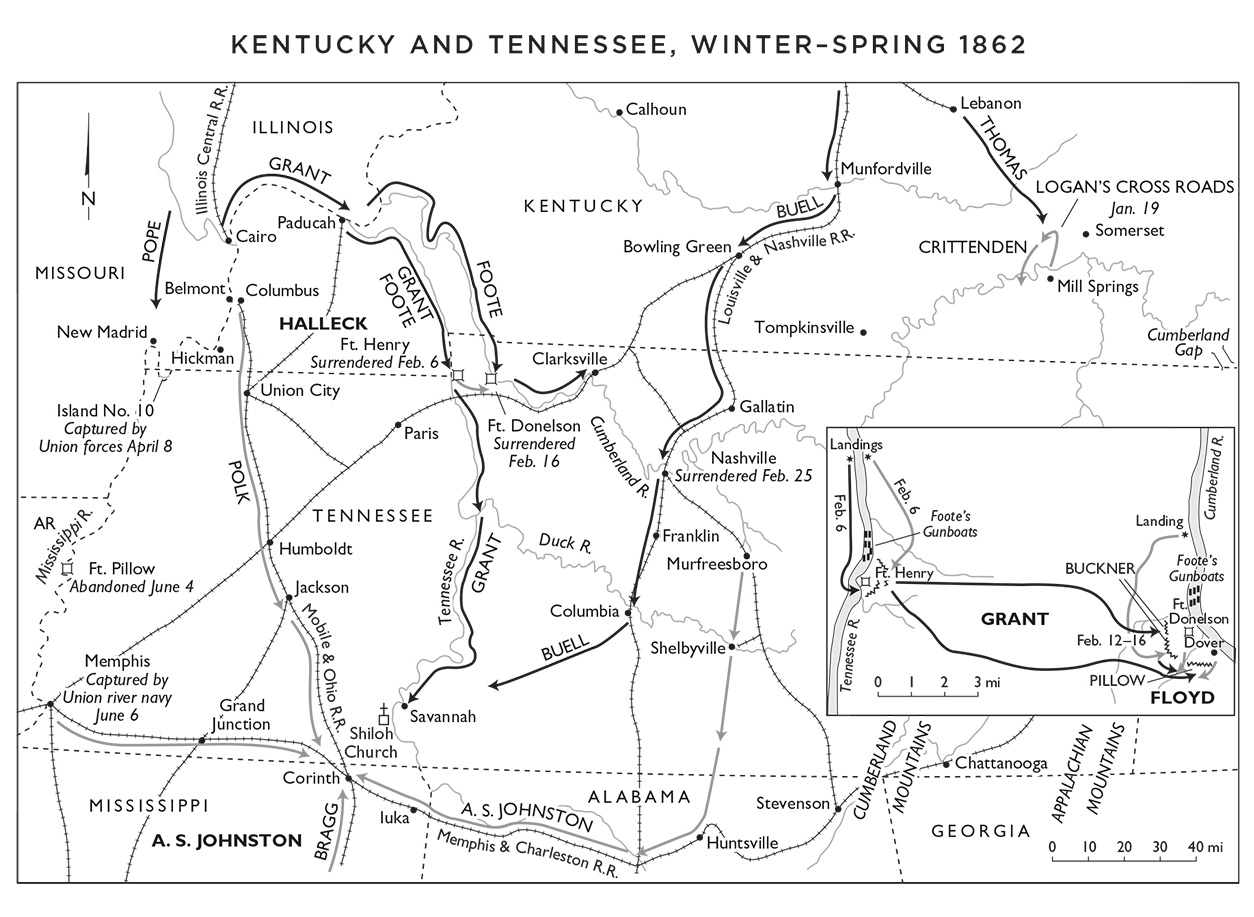

Meanwhile, Grant had been preparing to attack Johnston’s defenses at their most vulnerable points, Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers just south of the Kentucky-Tennessee border. Union naval power on the rivers gave its army a considerable advantage over the Confederates, who had virtually no navy on these waters. On February 6 the Yankee river ironclads captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. Two “timberclad” gunboats steamed all the way up the river to the rapids at Florence, Alabama, wreaking much damage along the way. They burned the railroad bridge that connected Johnston’s two main Kentucky forces at Columbus and Bowling Green, while Grant’s army prepared to march against Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River.

Albert Sidney Johnston

The fall of Fort Henry shocked Davis into taking the previously rejected step of divesting the Gulf Coast of troops to reinforce Johnston. On February 8 orders went out to Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg at Pensacola and Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell at New Orleans to send seven or eight thousand men to Tennessee and Kentucky.3 A few days later Davis ordered Bragg to abandon Pensacola (which the Federals then occupied) and go personally with the rest of his troops to Tennessee. He also ordered the river defense fleet of Confederate gunboats at New Orleans to go up the Mississippi River.4 These actions enabled the Federals to capture New Orleans and gain control of the lower Mississippi River two months later—precisely the consequences Davis had warned against in his earlier refusals to concentrate most Confederate forces in Virginia and Tennessee.

None of these reinforcements would reach Sidney Johnston in time to save Fort Donelson and Nashville. In an emergency meeting at Bowling Green on February 7, Johnston, Beauregard, and their staffs canvassed their strategic options. The grandiloquent Beauregard proposed one of his fanciful schemes to concentrate all available Confederate troops to “smash” Grant’s and Buell’s armies in turn. Johnston rejected this idea. He wanted to give up Kentucky and retreat to the Nashville-Memphis line, leaving only a token force at Fort Donelson to delay Grant and concentrating the rest of the army to fight under more favorable conditions. But for some unexplained reason, Johnston changed his mind and decided to make a real stand at Fort Donelson—perhaps because its loss would lay Nashville open to the Union river navy. Instead of taking his whole force to Fort Donelson, however, he sent twelve thousand men (increasing the total garrison to seventeen thousand) and retreated with the rest to Nashville.

The first- and second-ranking commanders at Fort Donelson—John B. Floyd and Gideon Pillow—belonged to that fraternity known as “political generals.” Floyd was a former governor of Virginia and secretary of war in the Buchanan administration; Pillow was a prominent Tennessee politician. Both Davis and Lincoln found it necessary as part of the mobilization of their polities for the war effort to appoint influential political leaders to military office. Some 30 percent of the general officers Davis named in 1861 belonged to this category.5 It was the Confederacy’s bad luck that two of them were in charge at Fort Donelson, where they faced two of the Union’s best professionals, General Ulysses S. Grant and naval Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. After an ineffective defense, Floyd and Pillow fled the scene and left the lone Confederate professional, Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, to surrender thirteen thousand troops to Grant on February 16. Nashville fell a week later.

A shower of recriminations fell on the heads of Johnston and Davis. The Confederate Congress appointed an investigating committee. Tennessee’s representatives and senators called for Johnston’s removal. So did a delegation from the Tennessee legislature. To the latter, Davis responded: “If Sidney Johnston is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no general.”6 Privately, however, Davis admitted that the criticisms “have been painful to me, and injurious to us both . . . and damaged our cause.” Attorney General Thomas Bragg noted that Davis “seems a good deal depressed—and though he holds up bravely, it is but too evident that he is greatly troubled.”7

Johnston acknowledged in a letter to Davis that the loss of Fort Donelson “was most disastrous and almost without remedy.” He understood the reasons for the clamor against him, and implied a willingness to resign if Davis wished it. “The test of merit in my profession, with the people, is success,” he acknowledged. “It is a hard rule, but I think it right.” Davis replied with an expression of reassurance. “My confidence in you has never wavered,” he told Johnston. “I hope the public will soon give me credit for judgment rather than continue to arraign me for obstinacy.”8 Davis showed no such magnanimity to Floyd and Pillow; he unceremoniously relieved them, and neither got another field command.9

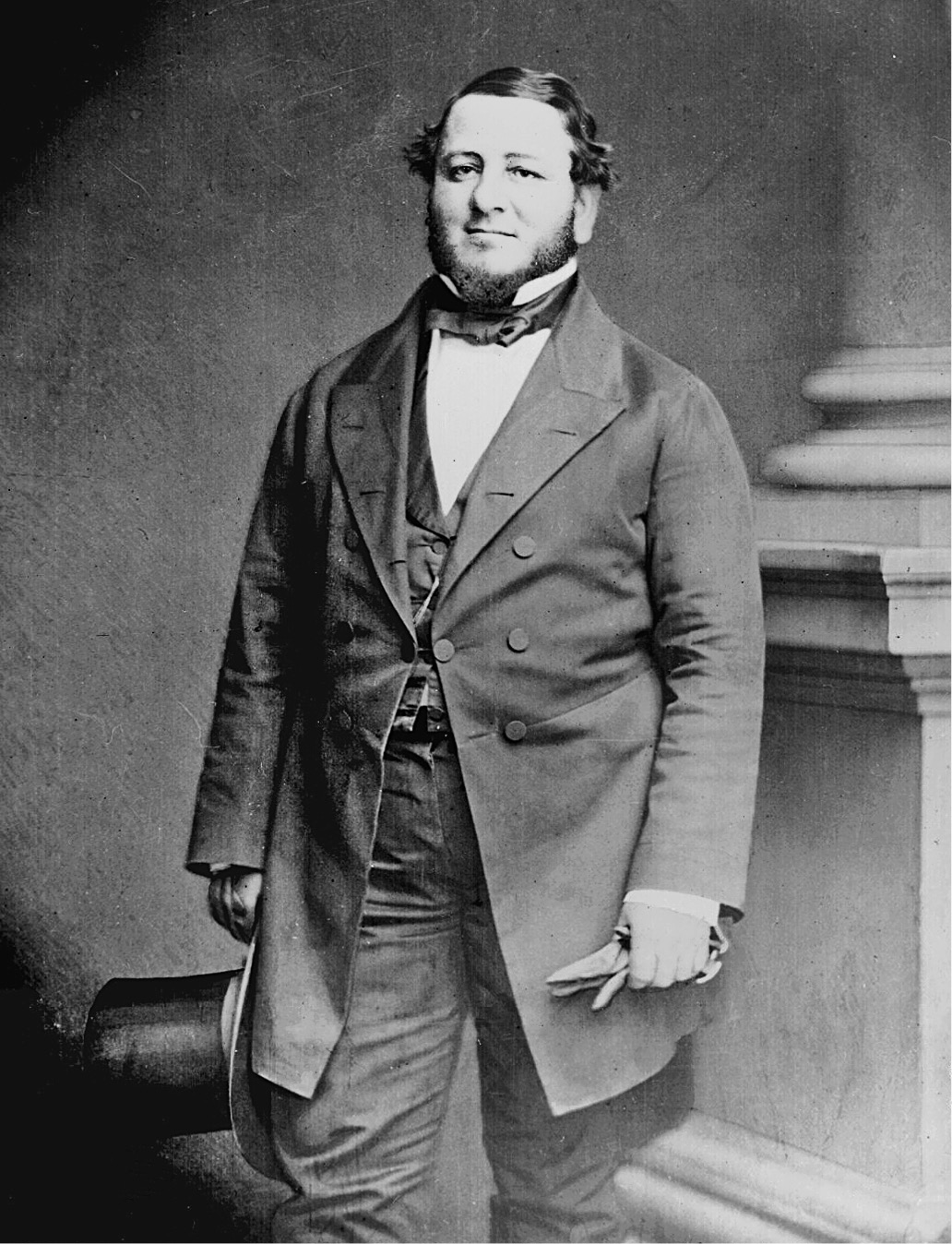

The loss of Kentucky and much of Tennessee was not the full extent of Confederate woes in February 1862. A Union task force of warships and army brigades attacked and carried Roanoke Island, key to control of Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds in North Carolina. From there the Federals occupied much of the state’s coastline, captured New Bern and Beaufort, and shut down all blockade running in and out of North Carolina ports except Wilmington. More than 2,500 Confederate soldiers surrendered at Roanoke Island. The son of Henry Wise, another influential political general, was killed in the battle there. North Carolinians had pleaded in vain with the Davis administration for more men and arms to defend their coast, but Secretary of War Judah Benjamin told them that he had none to send.

“Our President has lost the confidence of the country” was one of the milder comments of Virginia and North Carolina newspapers. “Davis’s incapacity was lamentable,” wrote the powerful Georgia politico and political general Robert Toombs, who had been a disappointed candidate for Davis’s office a year earlier.10 But most of the blame for the North Carolina defeats fell on Benjamin, who had been for months an unpopular secretary of war. Davis and Benjamin decided that the secretary should endure in silence the censure of a congressional investigating committee rather than reveal the Confederacy’s weaknesses to the enemy by testifying to the lack of arms and men that had made it impossible to reinforce Roanoke Island. Benjamin resigned as secretary of war; Davis replaced him with Virginian George Wythe Randolph, a grandson of Thomas Jefferson and a veteran of the prewar United States Navy and of the Confederate army in 1861–62. He was a popular choice; less popular was Davis’s appointment of Benjamin as secretary of state, a post in which he became one of the president’s closest advisers and confidants.11

In the midst of these troubles, Davis was inaugurated for a full six-year term as president of the Confederate States of America on February 22. Until then he had been provisional president, elected by the same convention that created the Confederacy and adopted its Constitution a year earlier. Under that Constitution an election for president and Congress was held in November 1861. Davis and his vice-presidential running mate, Alexander H. Stephens, had no opposition in the election; most candidates for Congress also ran unopposed. This show of unity was misleading, however, and by the time of Davis’s inauguration the seeds of an inchoate opposition were beginning to sprout as he became the target of reproach for Confederate setbacks.

Judah P. Benjamin

In his inaugural address, which he delivered outdoors in a pouring rain, the president took note of the altered mood of the public. “After a series of successes and victories, which covered our arms with glory, we have recently met with serious disasters,” he acknowledged. But the same was true of their forebears in the American Revolution. Southerners must “renew such sacrifices as our fathers made to the holy cause of constitutional liberty. . . . To show ourselves worthy of the inheritance bequeathed to us by the patriots of the Revolution, we must emulate that heroic devotion which made reverses to them but the crucible in which their patriotism was refined.” Although “the tide for the moment is against us, the final result in our favor is not doubtful. . . . It was, perhaps, in the ordination of Providence that we were to be taught the value of our liberties by the price which we pay for them.”12

Eloquent and inspiring words, but could they be matched by deeds? Davis hoped that a change from the strategy of a dispersed defense to one of concentration would accomplish that purpose. “I acknowledge the error of my attempt to defend all of the frontier, seaboard and inland,” he wrote privately. In a cabinet meeting on February 19, the president said that “the time had come for diminishing the extent of our lines—that we had not the men in the field to hold them and we must fall back.”13 Six days later Davis told Congress that “in the effort to protect by our arms the whole of the territory of the Confederate States” the government “had attempted more than it had power successfully to achieve.” He announced that “strenuous efforts have been made to throw forward reinforcements” to the main armies in Mississippi and Virginia.14

Sidney Johnston was concentrating all of his forces at the rail junction of Corinth in northern Mississippi. There he faced a threat from Grant’s army moving up the Tennessee River and Buell’s army marching overland to join Grant in a combined thrust to capture Corinth. Polk received orders to abandon his huge fortifications at Columbus, Kentucky, and bring his men to Corinth. In Arkansas, Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, who had fought and lost the Battle of Pea Ridge on March 7–8, also received orders to cross the Mississippi and join Johnston, abandoning Missouri and northern Arkansas to the enemy. Davis and Johnston intended to risk all on a counteroffensive to strike Grant at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River, twenty miles from Corinth, before Buell could join him. It would be the Confederacy’s first significant cast of the dice in a strategy of the offensive-defensive.15

After delays caused by the inexperience of the men and their officers, Johnston’s forty thousand soldiers finally attacked Grant’s thirty-five thousand on the morning of April 6 near a small log church called Shiloh. The initial Confederate assaults drove the unprepared Federals back with heavy losses to both sides. In midafternoon Johnston was hit in the leg by a bullet that severed an artery. He bled to death before his aides realized the seriousness of the wound. Beauregard took over and called a halt to the attack near dusk as Grant’s final line stiffened and reinforcements from Buell’s army began to arrive. That night Beauregard sent a telegram to Davis announcing “a complete victory driving the enemy from every position.” Davis’s face no doubt lit up when he read these words, but his shoulders sagged as he reached the concluding line announcing Johnston’s death. Nevertheless, the president sent Congress a message on April 8 informing it of a “glorious and decisive victory” and a retreating enemy.16 Unknown to Davis at that moment, however, it was the Confederates who were retreating in disarray to Corinth after Grant and Buell counterattacked on April 7.

Davis was crushed by this news when it reached Richmond on April 10. Johnston’s death turned out to have been in vain. Davis wept privately for the loss of his friend, which he pronounced “the greatest the country could suffer from. . . . The cause could have spared a whole State better than that great soldier.”17 To the end of his life Davis believed that Beauregard had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by not pressing the attack on the evening of April 6—a conviction shared by some but not all modern historians of the battle.

In response to Beauregard’s telegram announcing his retreat to Corinth, Davis uncharacteristically pushed the panic button. He wired the governors of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana to send all the men and arms they could spare to Beauregard “to meet the vast accumulation of the enemy before him.” The governors scraped together a few thousand troops; Joseph Brown of Georgia also offered to send a thousand pikes and knives. Davis replied: “Pikes and knives will be acceptable. Please send them.”18

Other reinforcements also reached Beauregard at Corinth, including nearly fifteen thousand men from Arkansas with General Earl Van Dorn, who had not arrived in time for the Battle of Shiloh. Beauregard vowed to hold Corinth “to the last extremity.”19 He faced a Union force composed of troops from the three armies of Grant, Buell, and Maj. Gen. John Pope, now united under the command of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the senior Union officer in the Western theater. Halleck advanced at a snail’s pace during May, threatening to envelop Corinth in a siege. Outnumbered almost two to one, with thousands of his troops on the sick list, Beauregard decided to pull out before he was surrounded. He did so skillfully on May 30, and retreated fifty miles south to Tupelo. Left isolated, with its rail connections to the east now severed, Memphis surrendered on June 6 to Union gunboats that had destroyed the Confederate Mississippi River fleet that day.

Beauregard wired Richmond that his “retreat was a most brilliant and successful one.” Davis was shocked and disgusted by this “brilliant” flight. He compared Beauregard to a man “who can only walk a log when it is near the ground.” He “has been placed too high for his mental strength, as he does not exhibit the ability manifested on smaller fields.”20 The president sent one of his aides, the son of deceased General Albert Sidney Johnston, with a series of written questions for Beauregard that signified his dissatisfaction with the general: Why did he not establish a stronger defensive position at Corinth? Why did he not attack the enemy’s communications? How much equipment did he lose in the retreat? What were his plans for future operations, “and what prospect [is there] of the recovery of the territory that has been yielded?”21

Before he could receive any answers, Davis learned that Beauregard had taken a leave of absence from the army, without permission or even notification of the government. The general had been in ill health for months, and he obtained a surgeon’s certification that he needed a rest of a week or ten days at a spa near Mobile. For Davis, this behavior was the last straw. He notified Beauregard that he was relieved of command and named Braxton Bragg as his successor.22

Beauregard got a much longer rest than he wanted. But because of the general’s popularity among segments of the press and public, Davis knew that he could not keep him on the shelf indefinitely. In September he gave Beauregard command of the defenses of Charleston, where he did an effective job of warding off Union attacks during the next year and a half. Beauregard remained bitter toward the president, however, calling him (in private) a “living specimen of gall & hatred . . . either demented or a traitor to his high trust. . . . If he were to die to-day, the whole country would rejoice at it, whereas, I believe, if the same thing were to happen to me, they would regret it.”23

• • •

THESE REVERSES IN THE WINTER AND SPRING OF 1862 CAME IN the midst of a crisis in army organization and recruitment. About half of all Confederate soldiers had enlisted for one year in 1861—despite Davis’s urging that Congress require three-year commitments. Their times would begin to expire in early 1862, creating the prospect that the armies would melt away just as the Yankees were advancing on all fronts. Congress tried to address this issue in December 1861 with a law offering one-year men who reenlisted a fifty-dollar bounty, a sixty-day furlough, and the opportunity to join new regiments and elect new officers if they did not like their old ones. This remedy was worse than the disease; it promised to disrupt the organization of many regiments more than expiring enlistments would have done. The various Southern states also had conflicting provisions for their militias, which created confusion when these troops were called into Confederate service. And in any case, few one-year men seemed to be reenlisting.

By March 1862 the new secretary of war, George W. Randolph; General Robert E. Lee, who had just returned from a four-month stint commanding defenses on the southern Atlantic coast; and Davis himself had become convinced that conscription was the only feasible solution. Randolph drew up legislation for this purpose; on March 28 Davis sent Congress a special message recommending the adoption of a measure making all white male citizens eighteen to thirty-five years old eligible to be drafted for three years. Davis initially opposed a provision requiring one-year men to serve for two more years; this would be a breach of contract, he argued. But Randolph convinced the president that this requirement was a military necessity, and Davis finally came around.

Opponents in Congress contended that conscription was a form of tyranny and coercion that Southern states had seceded to escape. But an overwhelming majority of the Senate and two-thirds of the House agreed with Senator Louis Wigfall of Texas, who warned his colleagues to “cease this child’s play. . . . The enemy are in some portions of almost every State in the Confederacy. . . . We need a large army. How are you going to get it? . . . No man has any individual rights, which come into conflict with the welfare of the country.” Davis signed the bill into law on April 16.24

The conscription law had some loopholes that stored up troubles for its enforcement: exemptions for some occupations crucial to war production (and some that were not); a provision that allowed a drafted man to hire a substitute; and confusion about which categories of state government officials and militia officers were exempt. Many of these issues would cross Davis’s desk in the next three years and cause him numerous headaches. The first—and most persistent—of those headaches was Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, who denounced the draft as a “dangerous usurpation by Congress of the reserved rights of the States” and said that it was “at war with all the principles for which Georgia entered into the revolution.”25

Davis plowed through Brown’s pamphlet-length letters condemning conscription and patiently replied, also at considerable length. The president explained the constitutional power of the Confederate government to draft men into the army. The Constitution authorized the government “to raise and support armies” and “to provide for the common defence.” It also contained another clause (likewise copied from the United States Constitution) empowering Congress to make all laws “necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” No one could doubt the necessity, wrote Davis, “when our very existence is threatened by armies vastly superior in numbers. . . . Congress has exercised only a plainly granted specific power in raising its armies by conscription. I cannot share the alarm and concern about State rights which you so evidently feel, but which seem to me quite unfounded.”26

Brown remained unconvinced and unmollified. He continued to be a thorn in Davis’s side. But Georgia also sent its full quota of troops, and perhaps more, into Confederate armies. Meanwhile, another issue raised its head and furnished fodder for a nascent opposition to the Davis administration’s “despotic” violation of civil liberties. This matter became an embarrassment for Davis. In his inaugural address on February 22, he had contrasted the Confederacy’s refusal “to impair personal liberty or the freedom of speech, of thought, or of the press” with Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus and imprisonment without trial of “civil officers, peaceful citizens, and gentlewomen” in vile “Bastilles.”27 Davis overlooked the suppression of civil liberties in parts of the Confederacy, especially East Tennessee, where several hundred Unionists languished in Southern “Bastilles.” Five days after Davis’s inaugural address, Congress authorized him to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in areas that were in “danger of attack by the enemy.”28

Davis promptly declared martial law in several places, including Richmond. Provost marshals enforced a requirement of passes for travel, banned sales of liquor, and jailed several “disloyal” citizens, including two women and John Minor Botts, a prominent Virginia Unionist and former United States congressman. At the same time, however, Davis did curb the excessive enforcement of such measures by some of his generals who commanded military departments. And unlike Lincoln, who suspended the writ on his own authority, Davis acted only when Congress authorized him to do so—for a total of seventeen months on three different occasions during the war. Nevertheless, the leading historian of civil liberties during the Civil War, Mark Neely, has found records of four thousand political prisoners in the Confederacy. The records are incomplete, and there were surely several thousand more. “Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis acted alike as commanders in chief when it came to the rights of the civilian populace,” Neely concluded. “Both showed little sincere interest in constitutional restrictions on government authority in wartime. Both were obsessed with winning the war.”29

• • •

FOR DAVIS THAT OBSESSION TOOK ON A SHARPER EDGE AS the Confederacy seemed to be losing the war in the West and along its coastline and rivers. Even in Virginia the outlook was dire in early 1862. “Events have cast on our arms and our hopes the gloomiest shadows,” Davis lamented to General Joseph E. Johnston in February.30 The president summoned Johnston to a strategy conference with cabinet members on February 19 and 20. For many hours they discussed the vulnerability of Johnston’s army at Centreville to a flanking movement by McClellan’s large force via the Occoquan or Rappahannock River. They agreed that Johnston should pull back to a more defensible position south of the Rappahannock. But the wretched condition of roads caused by winter rains and the chaotic state of the railroads made a quick withdrawal impossible. Davis ordered Johnston to send his large guns, camp equipage, and huge stockpiles of meat and other supplies southward as transportation became available, and to prepare to retreat with the army when he received definite orders.

In early March, however, Johnston began a precipitate withdrawal when his scouts detected Federal activity that he thought was the beginning of McClellan’s flanking movement. Without informing Richmond (he feared a leak), Johnston fell back so quickly that he was compelled to leave behind or destroy his heavy guns, ammunition, and mounds of supplies, including 750 tons of meat and other foodstuffs. In Richmond Davis heard rumors of this destruction and retreat, but as he later told the general, “I was at a loss to believe it.” When he finally heard the truth from Johnston on March 15, the president’s distress at the losses the Confederacy could ill afford was acute.31

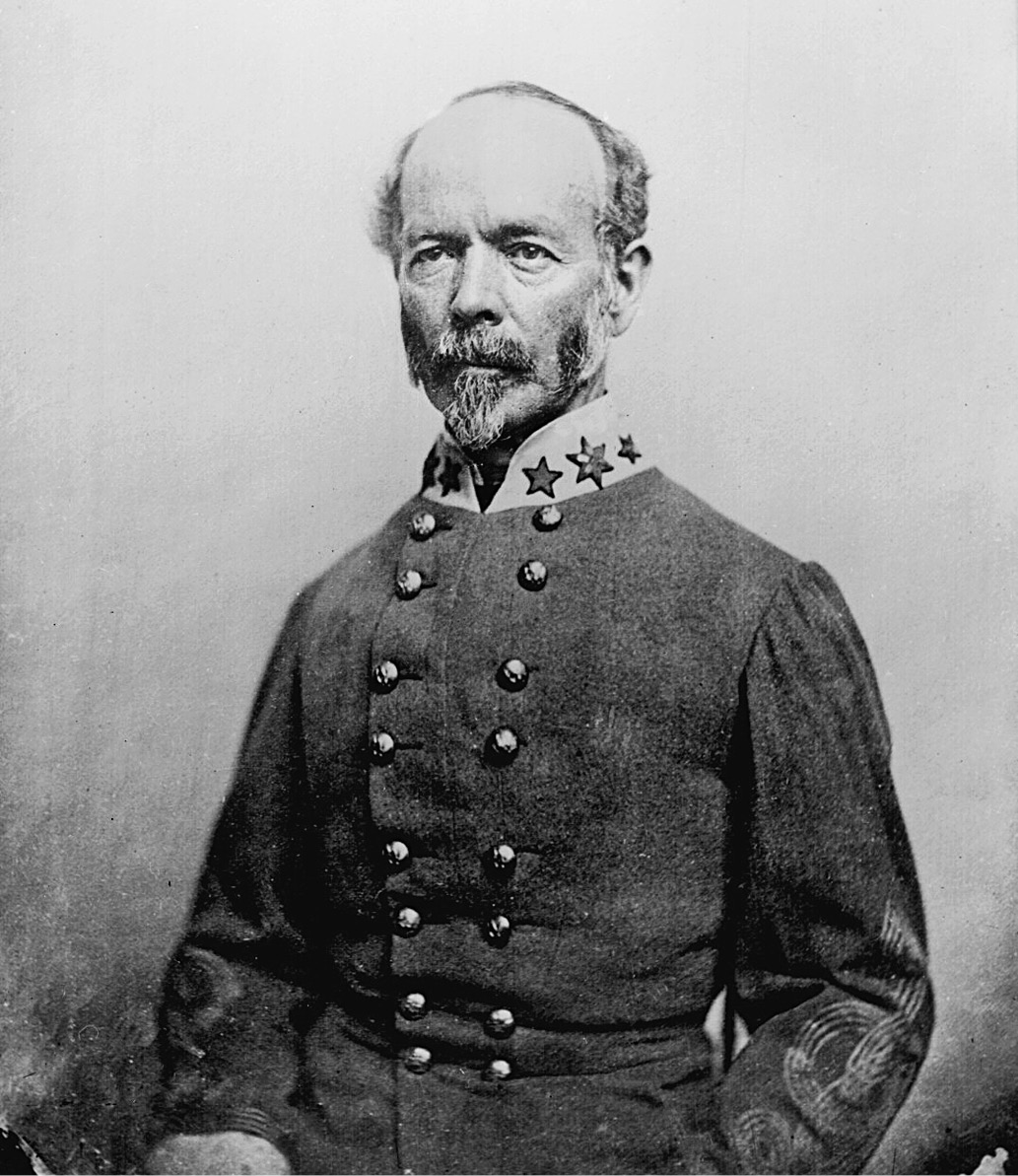

Joseph E. Johnston

Davis’s confidence in Johnston had been waning for some time. As things went from bad to worse during February and March, the president decided to recall Robert E. Lee from the southern Atlantic coast to become general-in-chief of all Confederate armies.32 Davis and Lee had known each other since their days at West Point (Davis graduated one year ahead of Lee). They had worked together cordially in the early months of the war when Lee served as a military adviser to the president after the government moved to Richmond. Davis used Lee as a sort of troubleshooter, sending him in July 1861 to western Virginia to regain control of the region from Union forces, and to South Carolina in November to reorganize coastal defense. For reasons largely beyond his control, Lee had failed to accomplish much in what became West Virginia and had met with partial success along the southern Atlantic coast only by withdrawing Confederate defenses inland beyond reach of Union gunboats.

Despite this mixed record, Davis retained his faith in Lee’s abilities and wanted him by his side. The president had his congressional allies introduce a bill to create the position of “Commanding General of the Armies of the Confederate States,” intending to name Lee to the post. But Davis’s critics in Congress, who blamed him for Confederate reverses, amended the bill to enable the “commanding general” to take direct control of any army in the field without authorization from the president. Davis believed that this provision would usurp his constitutional powers as commander in chief, and he vetoed the bill on March 14. A day earlier he had issued an order assigning Lee to duty in Richmond and charging him “with the conduct of military operations . . . under the direction of the President.”33

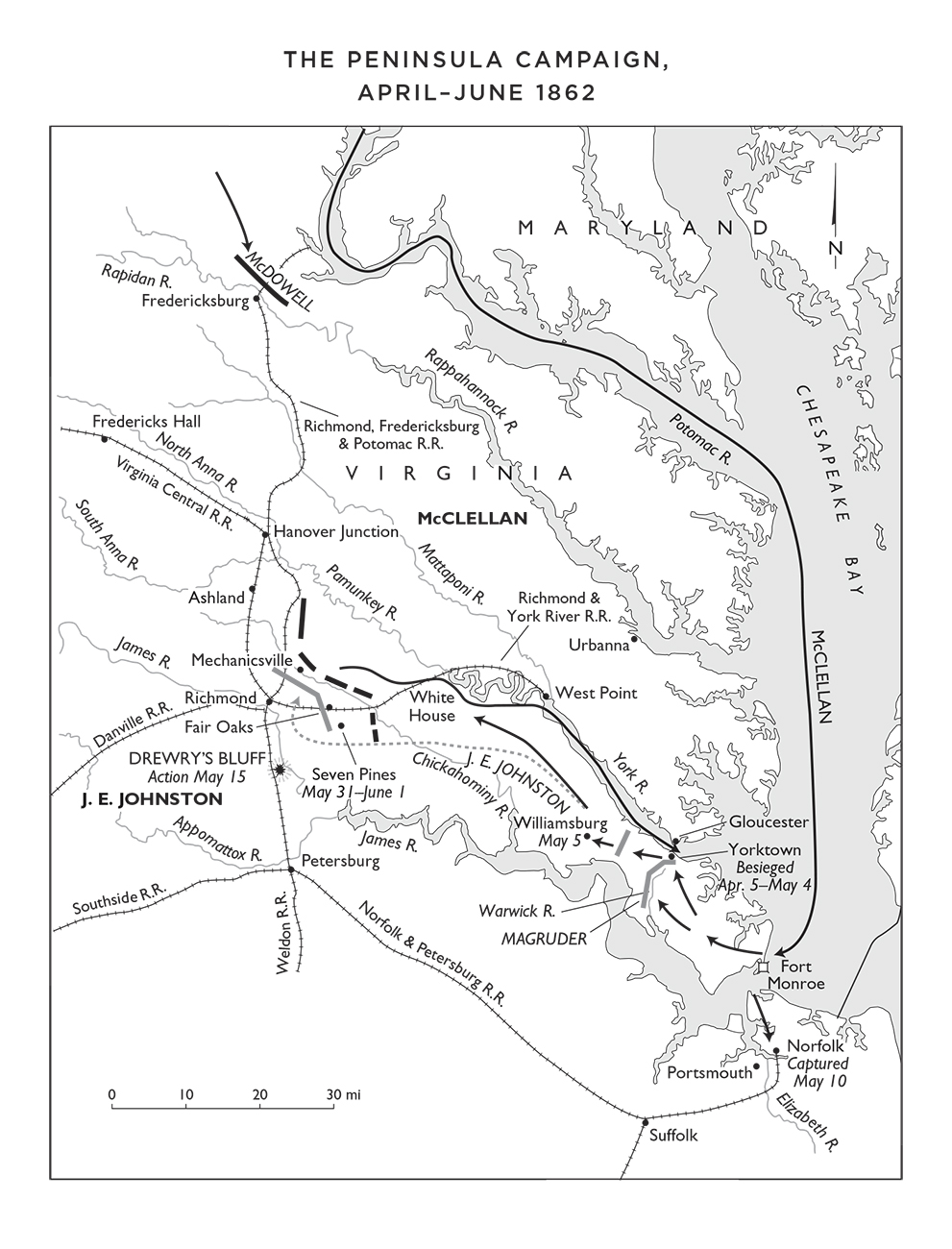

Lee’s first task was to help Davis decide what to do about the situation in Virginia. From his desk in Richmond, Lee instructed Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to make diversionary attacks with his small army in the Shenandoah Valley to prevent the Federals from concentrating all of their troops against Richmond. During the next two months Jackson carried out these orders in spectacular fashion. Meanwhile, McClellan’s army began landing near Fort Monroe at the tip of the peninsula in Virginia formed by the James and York Rivers, seventy miles southeast of Richmond. When the Federals advanced toward the Confederate defenses held by Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder’s twelve thousand troops, Davis and Lee ordered Johnston to send part of his army from the Rappahannock to Magruder. As the Union buildup continued, they instructed him to bring his whole army to the peninsula. Johnston proceeded to do so, but after inspecting Magruder’s line at Yorktown, he recommended that the Confederates withdraw all the way back to Richmond, concentrate the Virginia forces there, and strip the Carolinas and Georgia of troops to fight the decisive battle of the war at Richmond. Winning there, they could then reoccupy the regions temporarily yielded to the enemy.

Here was a bold suggestion for a high-risk strategy of concentration for an offensive-defensive of the kind later associated with Lee. But on this occasion Lee opposed the idea. In an all-day meeting of Davis, Lee, Johnston, and Secretary of War Randolph on April 14, Lee and Johnston discussed the matter at great length. Lee argued for making the fight at Yorktown, where the big guns at the Gloucester Narrows on the York River and the CSS Virginia on the James River would protect the army’s flanks. An old navy man, Randolph pointed out that pulling back from Yorktown would mean abandoning Norfolk with its Gosport Navy Yard, where the Virginia had been rebuilt from the captured USS Merrimack. Davis listened carefully to the arguments, took an active part in the discussion, and finally decided in Lee’s and Randolph’s favor. The Confederates would make their stand at Yorktown, where Johnston took command of 60,000 troops facing McClellan with 110,000.34

Instead of attacking, McClellan dug in his siege artillery and prepared to pulverize the Confederate defenses. This preparation continued for several weeks while the armies skirmished but did little damage to each other. Despite having been overruled by Davis, Johnston still intended to evacuate the Yorktown line without a fight. He delayed that move until McClellan was ready to open with his heavy artillery. Johnston failed to keep Davis and Lee informed of his intention until the last minute on May 1, when he told the president that he must pull out the next night. Davis was shocked. He replied that such a sudden retreat would mean the loss of Norfolk and possibly of the Virginia and other ships under construction there. Johnston consented to wait—for one more day. On the night of May 3–4 his army stealthily left the Yorktown line and began a retreat toward Richmond. The Confederates fought a rearguard battle with the cautiously pursuing Federals at Williamsburg, and continued to a new line behind the Chickahominy River twenty miles from Richmond. Norfolk fell to the enemy, and the Virginia’s crew had to blow her up because her draft was too great to get up the James River.35

Davis was dismayed by these developments. A congressman reported that he found the president “greatly depressed in spirits.” Davis’s niece from Mississippi was visiting the Confederate White House at the time. She wrote to her mother that “Uncle Jeff. is miserable. . . . Our reverses distressed him so much. . . . Everybody looks drooping and sinking. . . . I am ready to sink with despair.”36 Davis and several cabinet members sent their families away from Richmond for safety. The secretary of war boxed up his archives ready for shipment before the capital fell. The Treasury Department loaded its specie reserves on a special train that kept steam up for an immediate departure.37

Davis allowed his anguish to leak into a letter to Johnston lamenting “the drooping cause of our country.” The ostensible purpose of the letter was to prod Johnston into carrying out Davis’s orders to group regiments from the same state together in brigades as a boost to morale. “Some have expressed surprise at my patience with you when orders to you were not observed,” the president told his general. Johnston recognized this rebuke for what it was, an expression of exasperation with Johnston’s conduct of the campaign. If he had received such a letter from someone who could be “held to personal accountability,” Johnston told his wife, he would have challenged him to a duel.38

In this time of troubles, Davis turned to religion. He had been attending St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond and had grown friendly with its rector, the Reverend Charles Minnigerode. Davis could not remember whether he had been baptized as a child, so he asked Minnigerode to baptize him and confirm him as a member of the church on May 6.39 One of Davis’s newspaper tormentors, the Richmond Examiner, waxed sarcastic about this event: “When we find the President standing in a corner telling his beads, and relying on a miracle to save the country, instead of mounting his horse and putting forth every power of the Government to defeat the enemy, the effect is depressing in the extreme.”40

But Davis was in fact mounting his horse and exerting all of his energy to try to defeat the enemy. A fine horseman, Davis was in the habit of riding out in the afternoon for exercise and diversion. He used these occasions to visit army headquarters on the Chickahominy and the batteries placed at Drewry’s Bluff on the James River seven miles from Richmond to stop the Union navy. Those guns did indeed drive back Northern warships, including the Monitor, on May 15, saving Richmond from the fate of New Orleans three weeks earlier, when the city had surrendered with naval guns trained on its streets.

But Richmond still seemed in great danger from General McClellan’s large army approaching the capital at a snail’s pace. Although Johnston chose not to reveal his plans to Davis (or Lee), the president expected him to defend the line of the Chickahominy and even to launch a counterattack if he stopped McClellan along that sluggish stream. Davis still had not lost entire faith in Johnston, despite his previous disappointments. “As on all former occasions,” he told the general on May 17, “my design is to suggest not to direct, recognizing the impossibility of any one to decide in advance and reposing confidently as well on your ability as your zeal it is my wish to leave you with the fullest powers to exercise your judgment.”41

Unknown to Davis, Johnston had already decided to withdraw to a new position just three or four miles east of Richmond. When the president rode out the next day to visit Johnston on the Chickahominy, he was taken aback when he encountered the army before he had ridden more than a few miles. Davis confronted Johnston and asked why he had pulled back so close to the capital. The general replied that the ground was so swampy and the drinking water so bad in the Chickahominy lowlands that he had moved to better ground and a safer supply of water. Davis was unnerved. Do you intend to give up Richmond without a battle? he asked. Johnston’s reply was equivocal. The president responded with asperity. He told Johnston, according to one of Davis’s aides who was present, “that if he was not going to give battle, he would appoint someone to the command who would.”42

Davis rode back to Richmond and summoned his cabinet and General Lee to a meeting the following day. He also asked Johnston to attend, so that everyone could learn his intentions. The afternoon of the meeting, Davis wrote to his wife: “I have been waiting all day for [Johnston] to communicate his plans. . . . We are uncertain of everything except that a battle must be near at hand.”43 Johnston never showed up, but Davis went ahead with the conference, where he expressed his anxiety about the fate of Richmond. According to Postmaster General John Reagan, Lee became emotional. “Richmond must not be given up,” he declared. “It shall not be given up.” As Lee spoke, Reagan recalled, “tears ran down his cheeks. I have seen him on many occasions and at times when the very fate of the Confederacy hung in the balance, but I never saw him show equally deep emotion.”44

The next day Davis assured a delegation from the Virginia legislature that Richmond would indeed be defended. “A thrill of joy electrifies every heart,” wrote the diary-keeping War Department clerk John B. Jones. “A smile of triumph is on every lip.”45 Johnston finally seemed to get the message. He discovered that McClellan had crossed to the southwest bank of the Chickahominy with part of his army, leaving the rest on the other side. Johnston informed Lee that he intended to cross the stream with three divisions and attack the force on the northeast bank on May 22. Davis had earlier discussed precisely such a tactical operation with Lee, so he approved Johnston’s plan. On the twenty-second the president rode out to the bluff overlooking the Chickahominy, then down to the river itself, to “see the action commence,” as he wrote to his wife. But he found nothing happening and no one to tell him why the attack had been called off. Only later did General Gustavus Smith, whose division was to lead the attack, tell Davis that a local citizen had informed him that the enemy was strongly posted behind Beaver Dam Creek, so he had decided not to attack. This was not the first time that Smith had frozen under pressure. Davis was disconsolate. “Thus ended the offensive-defensive programme,” he wrote, “from which Lee expected much, and of which I was hopeful.”46

Almost the same scenario repeated itself exactly a week later, on May 29. Once again Johnston planned to attack McClellan’s right flank north of the Chickahominy, and once again he called it off without informing Davis. The president discovered the cancellation only after riding out to the river on another futile mission.47 Johnston had changed his mind and decided to assault the two corps south of the Chickahominy and nearest Richmond. The general later explained that he did not tell Davis of this change “because it seemed to me that to do so would be to transfer my responsibilities to his shoulders. I could not consult him without adopting the course he might advise, so that to ask his advice would have been, in my opinion, to ask him to command for me.”48

Johnston’s peculiar notion of the correct relationship with his commander in chief meant that Davis first learned of the general’s changed plan of attack when he heard artillery firing on the afternoon of May 31. He quickly left his office, mounted his horse, and rode toward the sound of the guns. When he arrived near the village of Seven Pines (which gave its name to the battle), he saw Johnston riding away toward the front. Davis’s aides were convinced that the general left to avoid the president. The battle was going badly for the Confederates. Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s division had taken the wrong road and blocked the advance of other divisions. The attack started late, and although it initially succeeded in routing one Union corps, reinforcements streamed across an almost flooded bridge over the Chickahominy and drove the Confederates back.

Davis came under artillery and musket fire as he and his aides tried to rally retreating soldiers. A reporter for a Memphis newspaper described the president “sitting on his ‘battle horse’ immediately behind our line of battle. . . . I was much struck with the calm, impassive expression of his countenance and his proud bearing as he sat erect and motionless, intently gazing at the enemy. . . . Bullets whistled plentifully around, but he never bootled his eye for them.”49

Davis issued orders and sent couriers for reinforcements, but as dusk approached it was clear that the Confederate attack had ground to a halt. At that moment, stretcher bearers passed the president’s party carrying a seriously wounded Johnston to the rear. All animosity forgotten, Davis rushed to Johnston’s side and spoke to him with genuine concern. “The old fellow bore his suffering most heroically,” Davis wrote to his wife. It was obvious that Johnston would be out of action for several months. As Davis and Lee rode together back to Richmond that night, the president told him that he was now the commander of what Lee would soon designate the Army of Northern Virginia. A new era would dawn with that army’s new name and new commander. “God will I trust give us wisdom to see and valor to execute the measures necessary to vindicate the just cause,” wrote Davis as he entered into his new command relationship with Lee.50