3.

WAR SO GIGANTIC

Although Confederate armies were driven back on all fronts in the spring of 1862, some voices continued to call for an invasion of the North. Even as the War Department and Treasury Department packed archives and gold reserves for possible evacuation, the Richmond Dispatch declared that the public favored “an advance into the enemy’s territory. Will the voice of the people again be denied?” The Charleston Mercury denounced the government’s “defensive policy” and urged that “two powerful columns . . . be put in motion toward the banks of the Ohio and the Susquehanna.”1 Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, normally insistent on retaining troops for local protection, unexpectedly offered Davis men from the state’s coastal defenses to help form an army “to liberate Tennessee, penetrate Kentucky, and menace Cincinnati. . . . Let us invade their Territory, and fight where there are plenty of provisions.” Virtually besieged in Richmond, Davis no doubt considered these entreaties delusional. But he thanked Brown for the offer, assured him that “such campaign as you suggest has long been desired,” and that “its adoption is a question of power, not of will.”2

With a like-minded general now in command of the newly named Army of Northern Virginia, Davis could contemplate at least a limited offensive to relieve the threat to Richmond. Stonewall Jackson’s operations in the Shenandoah Valley had temporarily reduced enemy pressure from that direction. Lee proposed to reinforce Jackson for a raid into Maryland and possibly even Pennsylvania, which he hoped “would call all the enemy from our Southern coast & liberate those states.” Davis concurred, and sent three brigades toward the valley. But even with these reinforcements Jackson would not be strong enough for a real invasion. Lee decided instead to carry out a plan originally suggested by Davis to bring Jackson from the valley to combine with Lee in a strike against the Union flank and rear north of the Chickahominy—similar to Johnston’s aborted maneuvers on May 22 and 29, with the added factor of Jackson’s cooperation.3

Brig. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart’s famous cavalry expedition that resulted in a ride completely around the Army of the Potomac (June 12–15) revealed that McClellan’s right flank was vulnerable to such an attack. To enable part of the Army of Northern Virginia to hold the line south of the Chickahominy so that the rest could take part in the flank attack, Lee ordered his troops to dig miles of trenches and build formidable earthworks. Complaining that they had enlisted to fight and not to work like slaves (in fact, actual slaves did much of this work), many soldiers and their allies in the press derisively labeled Lee the “King of Spades.”

Davis fully backed his general. He deplored the “politicians, newspapers, and uneducated officers” who “created such a prejudice in our army against labor that it will be difficult until taught by sad experience to induce our troops to work efficiently. ” McClellan was digging his way toward Richmond, noted Davis, and Confederates must neutralize his works. “If we succeed in rendering his works useless,” Davis explained to his wife, who was in North Carolina, “I will endeavor by movements which are not without great hazard to countervail the Enemys policy” by attacking his open flank. “I have much confidence in our ability to give him a complete defeat, and then it may be possible to teach him the pains of invasion and to feed our army on his territory.”4

A skirmish south of the Chickahominy provoked by a Union reconnaissance on June 25 became, in retrospect, the first of what was subsequently named the Seven Days’ Battles. The following day Lee put in motion the operations north of the river to attack the enemy flank at Beaver Dam Creek. Once again the commander in chief rode out to observe his army in battle; once again it began to appear that there would be no battle. Lee’s plan called for Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill’s division to attack when Jackson notified Hill that he was in position on the Union flank. As the hours ticked away, the silence grew oppressive among the Confederate officers with Lee and Davis waiting for the action to begin. In late afternoon Hill’s guns finally opened up, but Lee soon learned that Jackson was nowhere to be found, and Hill had grown tired of waiting. Slowed by felled trees over the roads, faulty maps, and the fatigue of his men and himself, Jackson was miles away.

Once Hill went in, it was too late to call off an attack that seemed headed toward bloody failure. Irritated and embarrassed, Lee noticed that Davis and an entourage that included aides, assorted politicians, and the secretaries of war and the navy had come under enemy artillery fire. Lee rode over to Davis and asked, with an edge to his voice, “Who are all this army of people, and what are they doing here?” Taken aback, Davis replied: “It is not my army, General.” “It is certainly not my army, Mr. President,” Lee responded, “and this is no place for it. . . . Any exposure of a life like yours is wrong.” Davis said meekly, “Well General, if I withdraw, perhaps they will follow me.” Suiting action to words, Davis turned his horse and moved away. As he did so, a soldier nearby was killed by an enemy shell. Davis rode only as far as a line of bushes along a stream that concealed him from Lee, then stopped, still within range of Union guns, to watch the backwash of Hill’s attack, which was repulsed with heavy loss by Federals dug in behind Beaver Dam Creek.5

Having won this round, McClellan decided to pull back his thirty thousand men north of the Chickahominy several miles to a new line behind Boatswain’s Swamp near Gaines’ Mill. Lee followed and launched a full-scale attack with fifty-five thousand men on June 27, this time including Jackson’s troops. After a series of failed assaults, the Confederates finally broke the enemy line toward dusk. The Federals again retreated, this time heading for a new base on the James River. Lee attacked repeatedly, at Savage’s Station on June 29, Glendale on June 30, and Malvern Hill on July 1, losing twice as many killed and wounded as the enemy but achieving a strategic victory by lifting the threat to Richmond.

Davis was present at each of these battles and even helped to rally stragglers on one occasion. At Glendale on June 30 he and Lee were both the subjects of another “Davis to the rear” incident. They were sitting on their horses under enemy artillery fire when General A. P. Hill rode up and declared: “This is no place for either of you, and, as commander of this part of the field, I order you both to the rear.” Abashed, they moved back, but not far enough to satisfy Hill. “Did I not tell you to go away from here?” he asked them with exasperation. “Why, one shell from that battery over yonder may presently deprive the Confederacy and the Army of Northern Virginia of its commander!” This time they moved out of range.6

The final Confederate assault at Malvern Hill was a costly failure. But McClellan nevertheless continued his retreat to Harrison’s Landing on the James River. Despite McClellan’s description of the retreat as a “change of base,” most people North and South alike regarded it as a humiliating defeat. Davis issued a congratulatory order to the Army of Northern Virginia that included a none-too-subtle hint of future Confederate operations. After this “series of brilliant victories” over an enemy “vastly superior to you in numbers and in the material of war, ” proclaimed the president, you will move on to “your one great object . . . to drive the invader from your soil, and carrying your standards beyond the outer bounds of the Confederacy, to wring from an unscrupulous foe the recognition of your birthright, community independence.”7

Davis gave private assurances that he meant what he said publicly. He agreed with critics who maintained that the ultimate consequence of purely defensive war was surrender. “There could be no difference of opinion as to the advantage of invading over being invaded,” he told John Forsyth, the mayor of Mobile and editor of the influential Mobile Register. However, “the time and place for invasion has been a question not of will but of power.” Davis reiterated that he had silently endured criticism of the defensive strategy during the earlier shortage of men and arms, “because to correct the error would have required the disclosure of facts which the public interest demanded should not be revealed.” But now, with a victorious army in Virginia and captures of weapons that ended the arms famine, the country could soon look for offensive operations. General Lee “is fully alive to the advantage of the present opportunity, and will, I am sure, cordially sustain and boldly execute my wishes to the full extent of his power.”8

Lee was if anything more offensive-minded than Davis. He did indeed intend to act “boldly.” Retaining part of his army to watch the idle Federals at Harrison’s Landing, Lee sent Jackson to confront the newly formed Union Army of Virginia under General John Pope moving against Richmond from the north. “We hope soon to strike another blow here,” Davis explained to one of his Western generals, “and are making every effort to increase the force so as to hold one army in check whilst we strike the other.”9 Jackson defeated part of Pope’s army at Cedar Mountain on August 9. When McClellan began to evacuate the peninsula to reinforce Pope’s army, Lee and Longstreet joined Jackson to assail Pope before McClellan’s men could join him. Davis stripped the Richmond defenses of veteran troops to bolster Lee’s force, leaving only raw recruits in the capital. “Confidence in you,” Davis telegraphed to Lee as he forwarded two full divisions to him, “overcomes the view that would otherwise be taken of the exposed condition of Richmond.”10

Robert E. Lee

Lee fully justified this confidence with a notable victory at the Battle of Second Manassas on August 29–30. Pope’s beaten army retreated into the Washington defenses, opening Maryland to the invasion that Davis had long wanted to undertake. Lee acknowledged to Davis that his army was “not properly equipped for an invasion of an enemy’s territory. It lacks much of the material of war, is feeble in transportation, the animals being much reduced, and the men poorly provided with clothes, and in thousands of instances, are destitute of shoes.” Nevertheless, “we cannot afford to be idle, and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass, if we cannot destroy them. . . . The movement is attended with much risk, yet I do not consider success impossible.”11

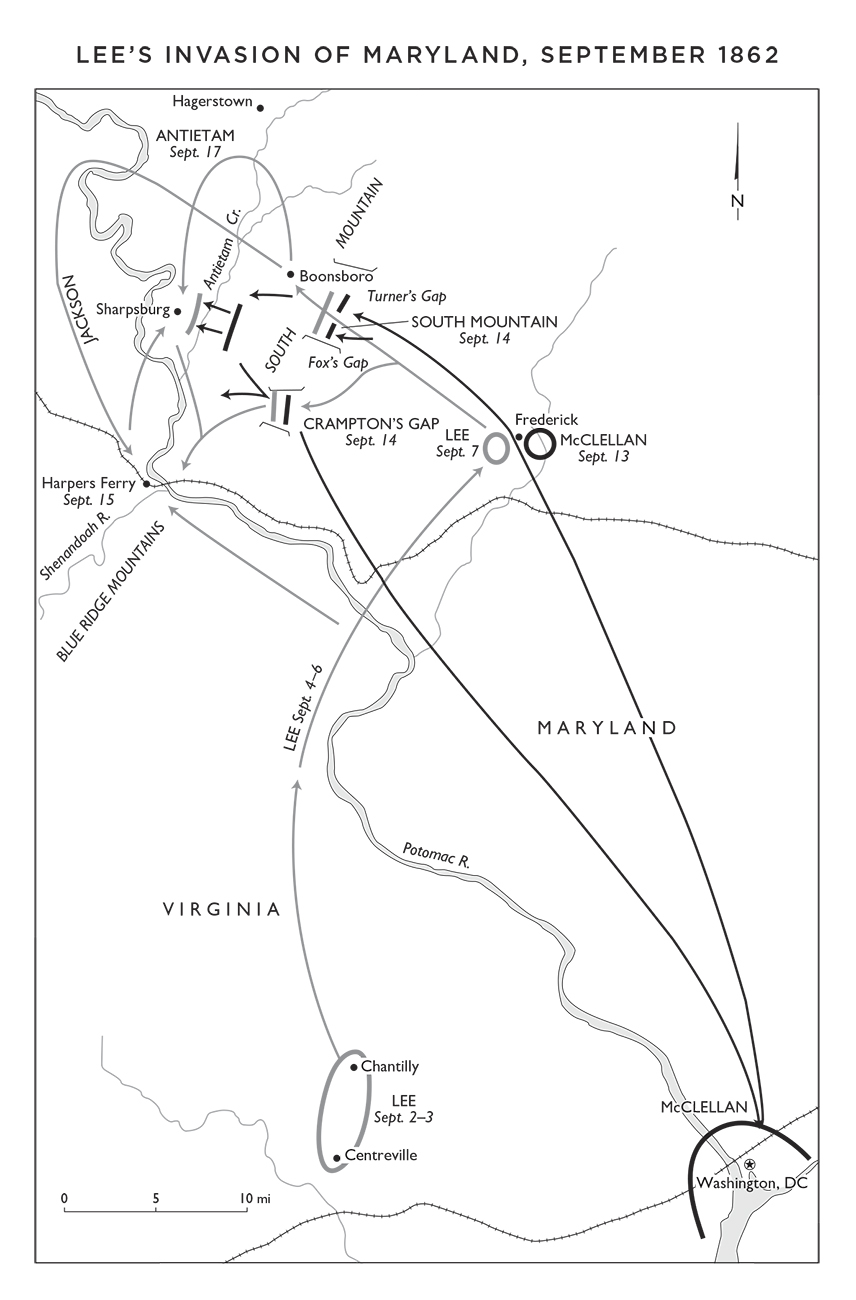

Neither did Davis, who recognized the political and diplomatic as well as military potential of the invasion. Northern “Copperhead” Democrats were denouncing the war as a failure and calling for peace negotiations. Upcoming Northern congressional elections might result in a Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives. “Liberation” of Maryland and its adherence to the Confederacy seemed possible. Davis was aware of the British and French desire for an end of the war and of the Union blockade that had drastically reduced imports of cotton and thrown thousands of their textile workers out of employment. Davis and Lee were avid readers of Northern newspapers smuggled across the lines. These papers were full of information about political unrest and diplomatic maneuvers that might lead to foreign recognition of the Confederacy. A successful invasion of Maryland and another victory over the Army of the Potomac might accomplish these ends. “The present posture of affairs,” Lee wrote to Davis on September 8, four days after he had crossed the Potomac into Maryland, “places it in our power . . . to propose [to the Union government] . . . the recognition of our independence.” Such a proposal, “coming when it is in our power to inflict injury on our adversary . . . would enable the people of the United States to determine at their coming elections whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination.”12

Davis intended to join Lee in Maryland to exploit these possibilities and to be present at the anticipated battle as he had been at those near Richmond. Fearing the danger of capture by roving Union cavalry, and probably not wanting Davis looking over his shoulder, Lee discouraged the president from coming. Davis nevertheless departed from Richmond on September 7 with a former governor of Maryland in tow, hoping to use his influence to attract Marylanders to the Confederacy. They got only as far as Warrenton, Virginia, and returned from there to Richmond the next day for reasons never explained. Davis’s fragile health had been giving him problems, which may explain his return.

As the president traveled back to his capital, Lee’s army was traveling in several directions in Maryland. Having cut the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad between Washington and the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Lee expected the Federals to evacuate that position, which lay athwart the Confederate supply route from the Shenandoah Valley. When they did not leave, Lee decided that he must capture Harpers Ferry before he could continue the invasion. He divided the army into five parts, three of them to converge on the enemy garrison. They succeeded in capturing Harpers Ferry and its twelve thousand defenders on September 15—the largest Confederate haul of Union prisoners in the war. But a copy of Lee’s orders for this operation, apparently lost by a careless Confederate courier, had been found wrapped around three cigars by two Union soldiers in a field near Frederick, Maryland, on September 13. This extraordinary stroke of luck gave Union general George B. McClellan information on the separation of the Army of Northern Virginia into several parts. Although McClellan and his subordinates did not move quickly enough to save Harpers Ferry from capture, he did attack the badly outnumbered Confederates along a stream named Antietam near the village of Sharpsburg on September 17. In a battle with the most casualties on a single day in the entire war (approximately twenty-three thousand killed, wounded, and missing in both armies), the Confederates were forced to retreat on the night of September 18–19. Davis was disappointed by the failure of the invasion to achieve its grand objectives, but with the record of the summer’s achievements in mind, he thanked Lee “and the brave men of your Army for the deeds which have covered our flag with imperishable fame.”13

• • •

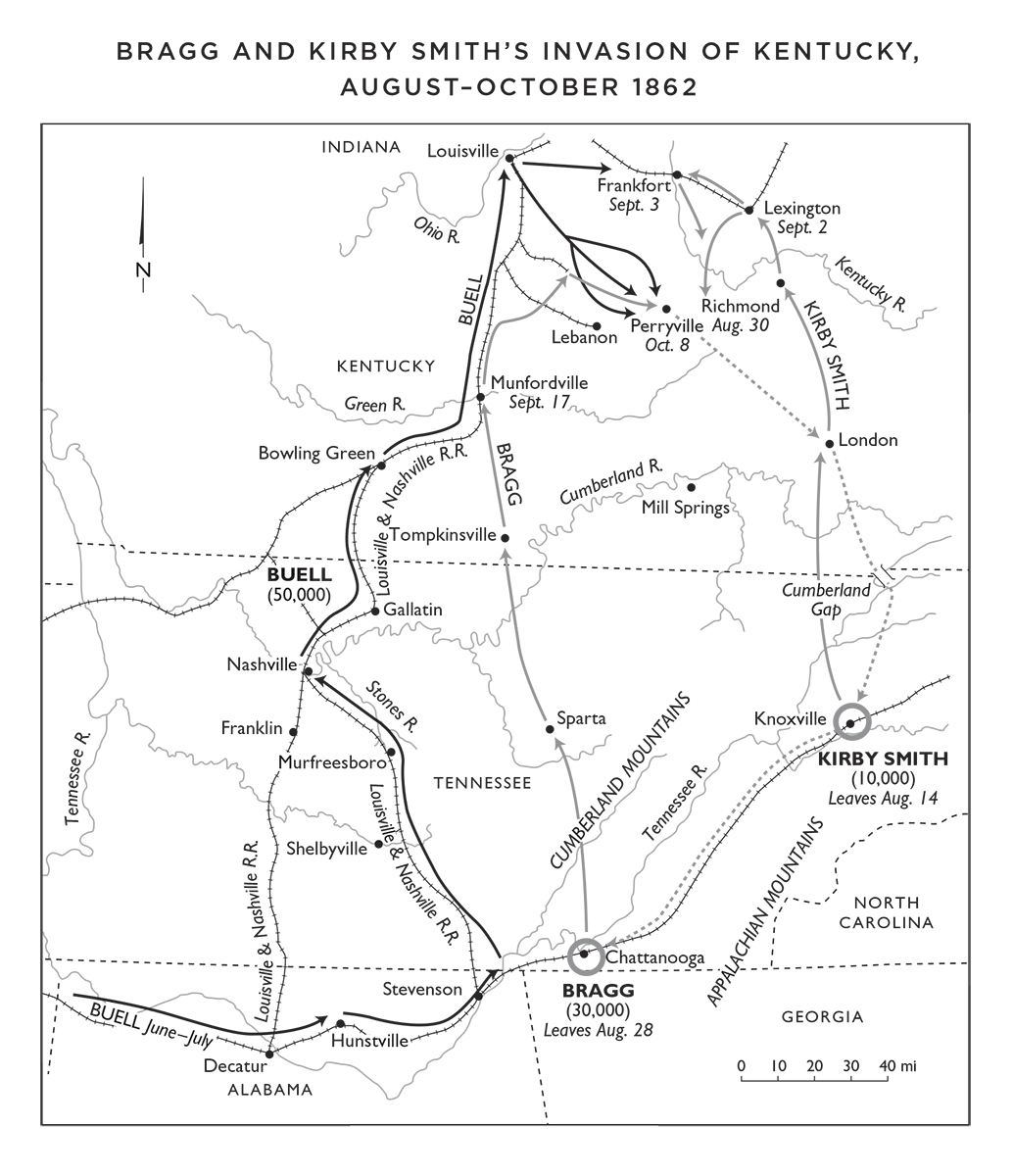

EVENTS IN TENNESSEE MAY HAVE ACCOUNTED FOR DAVIS’S decision to return to Richmond rather than continue on to Maryland to join Lee. As commander in chief, his place was in the capital rather than with a single army in the field. After Union general Henry W. Halleck’s occupation of Corinth, Mississippi, at the end of May, Lincoln called Halleck to Washington in July to become general-in-chief of all Union armies. Ulysses S. Grant took command of Union troops in northern Mississippi, while Don Carlos Buell began a glacial advance toward Chattanooga to carry out Lincoln’s cherished hope to “liberate” the Unionists of East Tennessee. Having taken command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, Braxton Bragg began making plans to counter this effort. Confederate cavalry raids on Union supply lines by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and Col. John Hunt Morgan slowed Buell’s progress. These successes encouraged Bragg to devise a more ambitious goal than merely defending Chattanooga. He moved his army over a circuitous route to that city, leaving behind about twenty-two thousand men under Generals Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price to harass Grant and if possible to recapture Corinth. Once he reached Chattanooga, Bragg proposed to move north from there and “produce [a] rapid offensive . . . following the consternation now being produced by our cavalry.” A Kentuckian, Morgan told Bragg that thousands in that state would join the Confederates as soon as a Southern army crossed the border.14

Davis was hearing the same information from his aide William Preston Johnston, also a Kentuckian and son of his late lamented friend Albert Sidney Johnston. Davis needed little persuasion. He too was convinced that Kentuckians under the iron heel of Lincoln’s hirelings were eager to join the Confederacy. He had already reinforced the small army of Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Department of East Tennessee with headquarters at Knoxville.15 Although Davis failed to create unity of command by placing Kirby Smith’s and Bragg’s armies under a single head (Bragg had seniority), he expected them to cooperate in a joint invasion of Kentucky. This cooperation, he told Kirby Smith, would “enable the two armies to crush Buells column and advance to the recovery of Tennessee and the occupation of Kentucky.” To Bragg he added: “Buell being crushed, if your means will enable you to march rapidly on Nashville, Grant will be compelled to retire to the [Mississippi] river, abandoning Middle and [West] Tennessee. . . . You may have a complete conquest over the enemy, involving the liberation of Tennessee and Kentucky.”16

This hopeful scenario seemed to be coming true in late August and early September. Kirby Smith’s force captured Richmond, Kentucky, along with more than four thousand Northern soldiers on August 30. On September 3 they occupied the state capital at Frankfort and prepared to inaugurate a Confederate governor. When this news reached Robert E. Lee just days after his army entered Maryland, he issued a general order to his troops announcing “this great victory” that was “simultaneous with your own at Manassas. Soldiers, press onward! . . . Let the armies of the East and West vie with each other in discipline, bravery, and activity, and our brethren of our sister States [Maryland and Kentucky] will soon be released from tyranny, and our independence be established on a sure and abiding basis.” Lee also issued a proclamation to the people of Maryland declaring that his army had come to help a state linked to the South “by the strongest social, political, and commercial ties” throw off “this foreign yoke” of Yankee occupation.17

Not to be outdone in the matter of proclamations, Davis issued his own to the people of Kentucky and Maryland explaining why Confederate armies had invaded their states. The South was “waging this war solely for self-defence,” Davis declared, and “it has no design of conquest or any other purpose than to secure peace and the abandonment by the United States of its pretensions to govern [our] people.” Confederate armies were in Kentucky and Maryland “to protect our own country by transferring the seat of war to that of an enemy who pursues us with a relentless . . . hostility.” Davis appealed to the people of these states to “secure immunity from the desolating effects of warfare on the soil of the State by a separate treaty of peace” with the Confederacy.18

The responses of people in Maryland and Kentucky were disappointing. Western Maryland was mostly Unionist in sentiment and few men from there joined the Army of Northern Virginia. Bragg wrote to Davis from Kentucky that “our prospects here . . . are not what I expected” from Colonel Morgan’s promise of thousands of recruits. Bragg had brought along some fifteen thousand muskets to arm Kentuckians, but only fifteen hundred joined up. “Enthusiasm runs high, but exhausts itself in words,” said Bragg in disgust.19

Bragg did achieve one success in Kentucky: the capture of the Union garrison of four thousand men at Munfordville on September 17. His continued advance northward threw a scare into Union forces at Louisville and created a panic in Cincinnati. But September 17 was also the day of the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, which forced Lee to retreat to Virginia. Three weeks later, Bragg’s Army of Tennessee fought to a draw with Buell’s Army of the Ohio at Perryville, Kentucky. Short of supplies, irked by the Kentuckians, and outnumbered by Buell, Bragg and Kirby Smith began the long retreat to Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Four days before the Battle of Perryville, a third leg of the Confederacy’s offensive-defensive bid for victory had also collapsed when Van Dorn’s and Price’s effort to recapture Corinth had been bloodily repulsed.

Davis confessed himself “sadly disappointed” with the outcome of these campaigns. The chief administrative officer in the War Department said that the president “considers this the darkest and most dangerous period we have yet had.” He was “very low down after the battle of Sharpsburg” (the Confederate name for Antietam). “He said our maximum strength had been laid out, while the enemy was but beginning to put forth his.”20

Confederate armies were forced to go over to the defensive again. The three main Union armies, two of them under new commanders, launched new offensives in November and December. In Mississippi, Grant moved against Vicksburg; in Tennessee, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, who renamed his command the Army of the Cumberland when he replaced Buell, marched out of Nashville against Bragg at Murfreesboro. And Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who replaced McClellan, aimed his army at the Confederate defenses on the hills above the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg.

Davis also faced renewed pressures from governors around the Confederate periphery who resented the concentration of troops from their states in the main Confederate armies in Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi. North Carolinians, including newly elected Governor Zebulon Vance, complained of neglect of the state’s coastal defenses and asked for the return of North Carolina troops from Virginia. Davis responded that the best defense of North Carolina consisted of a strong army in Virginia “at a point where they can offer the most effective resistance.” To the commander of Charleston’s defenses, Davis explained that his call for South Carolina regiments to come to Virginia “was the result of pressing necessity. . . . You can estimate the consequences to the common cause which depend upon success here.”21 When the governors of Florida and Alabama lamented “disaster after disaster” to scattered coastal areas that enabled the enemy to make numerous lodgments along their shores, Davis commiserated with them but noted that “the enemy greatly outnumber us and have many advantages in moving their forces [by water] so that we must often be compelled to hold positions and fight battles with the chances against us. Our only alternatives are to abandon important points or to use our limited resources as effectively as the circumstances will permit.”22

Davis’s ambiguous explanation provided cold comfort to these governors, who nevertheless remained loyal supporters of the Confederate government. More troubling were the protests and threats from Louisiana and Arkansas, largely cut off from the rest of the Confederacy by Union control of most of the Mississippi River. Nearly all Confederate troops still in Louisiana had been transferred to northern Mississippi after the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, enabling the enemy to occupy New Orleans and most of southern Louisiana. The governor bewailed “the calamity that has deprived us of our metropolis, severed the State, and rendered all the banks of our navigable rivers . . . vulnerable to the enemy’s armed vessels.” All thirty Louisiana regiments were serving outside the state, he reminded Davis, and “knowing the necessity of massing the Confederate troops at vital points, I do not ask or expect soldiers to be withdrawn from our great armies” to defend what remained of Confederate Louisiana. But “no more men or arms should be spared for distant service until the yet uninvaded part of the State is guarded against marauders.”23

The governor of Arkansas went even further and threatened to secede from the Confederacy if the state was left undefended. Most troops in Arkansas had been ordered east of the Mississippi in April 1862 to help defend Corinth, and remained there even after that city fell. Union forces occupied northern Arkansas. The angry governor issued a proclamation deploring “Arkansas lost, abandoned, subjugated.” She “is not Arkansas as she entered the confederate government. Nor will she remain Arkansas a confederate State desolated as a wilderness.”24

Davis responded not by returning the troops but by sending Arkansan Thomas Hindman to command the Trans-Mississippi Department with his headquarters at Little Rock. A dynamo only five feet tall, Hindman declared martial law and ruthlessly enforced conscription. His methods aroused howls of protest, but he did create a new army in the state. The complaints caused Davis to send his old friend Theophilus Holmes, a North Carolinian who had proved ineffective as a division commander during the Seven Days’ Battles, to replace Hindman.25

A genial but mediocre administrator, handicapped by near deafness, Holmes was soon whipsawed between the pressures of local defense and the demands for troops to help defend Vicksburg. In a command reshuffle to provide General Beauregard with a new position, Davis had promoted John C. Pemberton to lieutenant general and given him command at Vicksburg. Beauregard succeeded Pemberton in charge of the Charleston defenses. Pemberton had been unpopular in Charleston, in part because of his Pennsylvania birth. He had married a Virginian and had chosen to side with his wife’s state instead of his own. This allegiance by choice rather than nativity was proof to Davis of the firmness of his convictions, but not to the prideful Carolinians—nor to the Mississippians, who were suspicious of this “Yankee general” from the outset.

Pemberton faced a two-pronged Union campaign against Vicksburg in December 1862: Grant with forty thousand men was advancing overland from West Tennessee, while William T. Sherman with thirty thousand moved down the Mississippi River supported by a powerful naval squadron. Outnumbered two to one, Pemberton needed all the help he could get. Davis repeatedly urged Holmes to send him reinforcements—ten thousand men or more if he could spare them. But the president did not put this request in the form of an order, and was reduced to pleading with his Trans-Mississippi commander. The best defense of Arkansas, Davis told Holmes, was to maintain control of the Mississippi River between Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana. If Vicksburg was lost, the enemy “will be then free to concentrate his forces against your Dept., and ’though your valor may be relied upon to do all that human power can effect, it is not to be expected that you could make either long or successful resistance.”26

Holmes resisted Davis’s logic. He responded that he did not have the number of troops in Arkansas that Davis thought he had; many of those he did have were on the sick list; others were hundreds of miles away and could not get to Vicksburg in time; and—most important—they would desert if sent east of the Mississippi, and the people of Arkansas would revolt. The governor backed Holmes’s arguments. “Soldiers do not enter the service to maintain the Southern Confederacy alone,” he lectured Davis, “but also to protect their property and defend their homes and families.”27

In the end the matter became moot. A raid by Van Dorn’s cavalry on the Union supply depot at Holly Springs, Mississippi, forced Grant to turn back, and Pemberton’s troops repulsed Sherman’s attack at Chickasaw Bluffs on December 29. Davis acceded to Holmes’s resistance to his entreaties. “If you are correct as to the consequences which would follow,” the president acknowledged, “you have properly exercised the discretion which was intrusted to you.”28

• • •

THIS AFFAIR BECAME INTERTWINED WITH ANOTHER DEVELOPMENT that exposed flaws in Davis's leadership style. He buried himself in paperwork, spending long hours reviewing every kind of document that came into the War Department as well as his own office, sometimes as many as two hundred in a single day. Many of these papers concerned minutiae like the promotion of junior officers, bake ovens for soldiers in camp, details of army administration, and similar “little trash which ought to be dispatched by clerks in the adjutant general’s office,” according to the chief administrator of the War Department. One of those clerks noted that “the President sent a hundred papers to the department to-day, which he has been diligently poring over, as his pencil marks bear ample evidence. They were nearly all applications for office, and this business constitutes much of his labor. . . . He works incessantly, sick or well.”29

As an administrator, Davis simply could not bring himself to delegate authority. His obsessive concern with military matters “induces his desire to mingle in them all and to control them,” complained Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory. “This desire is augmented by the fear that details may be wrongly managed, without his constant supervision.” This same absorption in details spilled over into meetings with his generals, which occasionally lasted late into the night. He met with individual cabinet members almost daily, and held two or three sessions weekly with the full cabinet. “These meetings occupied from two to five hours, far longer than was required,” wrote Mallory. “From his uncontrollable tendency to digression,—to slide away from the chief points to episodical questions, the amount of business accomplished bore but little relation to the time consumed; and frequently a Cabinet meeting would exhaust four or five hours without determining anything, while the desk of every chief of a Department was covered with papers demanding his attention.”30

Davis was far more preoccupied with army matters than with the navy; consequently, he granted much greater autonomy to Mallory than to the secretary of war. Mallory served during the entire conflict; five different men (not including one brief interim appointment) occupied the office of secretary of war. In effect, Davis was his own secretary of war much of the time. George Wythe Randolph became increasingly restive under these circumstances. In almost identical language, two War Department officials wrote that Davis reduced Randolph to the “humble capacity” of “a mere clerk.” The president “issued orders, planning campaigns, as in East Tennessee, which he neither consulted the Secretary about nor apprised him of. He appointed general officers, sending their names to the A[djutant] G[eneral]’s office without consultation, the first information the Secretary received being that the commissions were brought to him to sign.”31

Stephen R. Mallory

In September 1862, Randolph told a friend that he had made up his mind to resign “because of the arrogance to which he was constantly subjected by the President.”32 A dispute concerning General Holmes’s troops in Arkansas provided the occasion for his resignation in mid-November. Without consulting the president, Randolph authorized Holmes to cross the Mississippi and join Pemberton for a campaign against Grant. This plan was different from Davis’s own efforts to persuade Holmes to send part of his force to Pemberton but to remain personally in Arkansas with the rest of them. Davis rebuked Randolph for not checking with him before issuing the orders to Holmes. Randolph immediately submitted his resignation. With an expression of irritation, Davis accepted it.33

“A profound sensation has been produced in the outside world” by Randolph’s resignation, wrote the diary-keeping War Department clerk John B. Jones. “Most of the people and the press seem inclined to denounce the President, for they know not what.”34 Some editors and politicians who professed to resent what they considered Davis’s hauteur seized on the Randolph case to condemn the president. Too busy—and disdainful—to reply to his critics, Davis appointed another Virginian, James Seddon, as secretary of war. The two men were acquaintances of long standing. Although Seddon once complained that Davis was “the most difficult man to get along with he had ever seen,” the secretary usually managed the relationship with tact and patience.35 Seddon remained in his job for more than two years, the longest tenure of any of the five secretaries of war.

James Seddon

• • •

DAVIS CONFRONTED ADDITIONAL AWKWARD PERSONNEL issues in November 1862. Having recovered from his wounds, General Joseph E. Johnston reported himself fit for duty. But what duty? Johnston would have preferred reassignment to his old command, now the Army of Northern Virginia. But Robert E. Lee had made that army his own, and even Johnston recognized that reality. More problematic than what to do with Johnston were the loud rumblings of discontent with Braxton Bragg in the Army of Tennessee. Two of Bragg’s principal subordinates—Generals Leonidas Polk and William Hardee—plus General Edmund Kirby Smith, whose Army of East Tennessee had operated jointly with Bragg’s army in the invasion of Kentucky, blamed Bragg for the failure of that campaign. In truth, they were motivated in part by a desire to deflect well-deserved blame from themselves.

These early signs of dysfunctional command relations in the Army of Tennessee had deep roots. Part of the problem was Bragg’s personality, which contemporaries described with a remarkable litany of adjectives: disputatious, cantankerous, irascible, austere, severe, stern, saturnine. But Davis had admired Bragg ever since his volunteer Mississippi regiment had fought beside Bragg’s artillery regulars at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican War. Bragg’s organizational and disciplinary skills had molded the best corps in the army that fought at Shiloh. When Davis decided to relieve Beauregard for taking an unauthorized leave after Shiloh, Bragg was a natural choice to replace him. Almost immediately, however, Beauregard’s supporters in the press and Congress, who formed the beginnings of an anti-Davis faction, began beating the drums for Beauregard’s reappointment—which required them to denigrate Bragg. “You have the misfortune of being regarded as my personal friend,” Davis wrote to the general in August 1862, “and are pursued therefore with malignant censure, by men regardless of truth and whose want of principle to guide their conduct renders them incapable of conceiving that you are trusted because of your known fitness for command.”36

Davis was therefore predisposed to take Bragg’s side in the finger-pointing about who was responsible for the failure of the Kentucky campaign. But that position was complicated by his long-standing friendship with Polk, who was the main figure in the anti-Bragg cabal. The Kentucky lobby in Richmond, which included Davis’s aide William Preston Johnston, also resented Bragg because of his outspoken criticism of the Kentuckians’ reluctance to come to his support during the invasion. Davis summoned Bragg, Polk, and Kirby Smith separately to Richmond and tried to smooth over their conflicts. He acknowledged that “another Genl. might excite more enthusiasm, but as all have their defects I have not seen how to make a change with advantage.” Beauregard would not do. He “was tried as commander of the Army of the West and left it without leave when the troops were demoralized and the country he was sent to protect was threatened with conquest.”37 Davis urged Polk and Kirby Smith to give Bragg their cordial support for the good of the cause, and rewarded (bribed?) them in advance with promotions to lieutenant general.

Recognizing that these moves might not accomplish the purpose, Davis attempted to resolve both of his personnel problems by appointing Johnston commander of the new Department of the West embracing all of the territory between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Johnston’s mission would be to coordinate the actions of the three main Confederate armies in this vast region: Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, Kirby Smith’s Army of East Tennesee, and Pemberton’s Army of Mississippi. Johnston thought that this command should also include Holmes’s Trans-Mississippi Department so that Holmes could be ordered to cooperate with Pemberton in the defense of Vicksburg. Although Davis favored such cooperation, he decided—perhaps unwisely—to keep the Trans-Mississippi separate.

On paper, Johnston’s new assignment appeared to be the largest and most important of the war. But he began to complain almost from the first that his real authority was minimal. Davis’s requirement that all three army commanders should continue to report directly to Richmond as well as to Johnston seemed to lend substance to this complaint. Nevertheless, Johnston could have made more of this command if he had chosen resolutely to do so.38

To sort out some of these issues and to rally flagging Southern spirits, Davis decided to make a trip to Johnston’s new theater, accompanied part of the time by the general. Leaving Richmond on December 9, Davis went first to Bragg’s headquarters at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He reviewed the army and found it in better condition and less threatened by the enemy than he expected. Indeed, Davis thought that Pemberton was more vulnerable than Bragg, and wanted to send a large division of nine thousand men from Murfreesboro to reinforce Pemberton. Both Bragg and Johnston protested that this detachment might fatally weaken Bragg and that Pemberton should be reinforced by troops from Holmes in Arkansas. Davis had of course already tried to get Holmes to send some of his men across the river, but without success. He overruled Johnston’s objections and ordered the division to Vicksburg. Part of it arrived in time to help repel Sherman’s attack at Chickasaw Bluffs on December 29. But Bragg would sorely miss the division in the Battle of Murfreesboro (called Stones River by the Federals) December 31–January 2, when its absence may have made the difference between victory and defeat.39

Davis’s rejection of Johnston’s advice in this matter of reinforcing Pemberton seemed to confirm the general’s belief that his theater command was merely nominal. In any event, the two men went on to Mississippi to inspect Vicksburg’s defenses. At several places during this trip and during his return journey to Richmond, where he arrived January 4, Davis gave speeches intended to lift morale and support for the war effort. One of the purposes of the trip, as he had explained to General Lee before he departed, was “to arouse all classes to united and desperate resistance.”40

The best way to do this, Davis believed, was to recite a long list of Yankee atrocities. He had used this rhetorical device since almost the beginning of the war. As early as July 1861 he had informed the Confederate Congress that the Federals were acting “with a savage ferocity unknown to modern civilization . . . committing arson and rapine, the destruction of private houses and property. . . . Mankind will shudder to hear the tales of outrages committed on defenseless females by soldiers of the United States” and of whispered words in the ears of slaves “to incite a servile insurrection in our midst.”41 In the war’s first year, however, Davis more often focused on themes of constitutional liberty, state sovereignty, and self-government as motives for fighting. But when his own government was compelled to enact conscription, suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and arrest opponents of the war, Davis came under attack for violating the very principles he professed to be fighting for. In consequence, his rhetoric shifted toward an emphasis on enemy atrocities as “a means to unite the southern people, strengthen their determination to resist, and prove the justice of the Confederate cause.”42

This emphasis was much in evidence in Davis’s speeches during the western trip. In response to an invitation from the Mississippi legislature, he spoke to an overflow crowd in Jackson the day after Christmas. “The dirty Yankee invaders” were a “traditionless and homeless race” descended from English Puritans “gathered together by Cromwell from the bogs and fens” of Britain, Davis declared. “They persecuted Catholics in England, and they hung Quakers and witches in America.” Now they were waging a war “for conquest and your subjugation, with a malignant ferocity and with a disregard and a contempt for the usages of civilization.” Davis was just getting warmed up. When he arrived back in Richmond, he told a crowd gathered to greet him that “you fight against the offscourings of the earth.—(Applause.) . . . By showing themselves so utterly disgraced that if the question was proposed to you whether you would combine with hyenas or Yankees, I trust every Virginian would say, give us the hyenas.—(Cries of ‘Good! good!’ and applause.)”43

While in Mississippi, Davis had taken time out from his consultations with Johnston and Pemberton to issue a proclamation branding Union general Benjamin Butler “an outlaw” and a “felon deserving capital punishment.” Butler had commanded the Union troops occupying New Orleans and southern Louisiana. He executed a Southern civilian for tearing down the American flag from the U.S. Mint, plundered property, seized slaves, and even armed them “for servile war—a war in its nature far exceeding in horrors the most merciless atrocities of the savages.” If captured, Butler should be “immediately executed by hanging” and all commissioned officers serving under him should be treated as “robbers and criminals, deserving death; and that they and each of them be, whenever captured, reserved for execution.”44

By the time Davis returned to Richmond, Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which included a provision stating that freed slaves would be accepted into the armed services of the United States. In a message to his Congress, Davis denounced Lincoln’s proclamation as “the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man.” It was the last straw among every conceivable atrocity committed by the armed forces of the United States. It was the “fullest vindication” of the South’s decision to secede in 1861, because it provided “the complete and crowning proof of the true nature” of Northern designs to abolish slavery. Davis announced an intention to “deliver to the several State authorities all commissioned officers of the United States that may hereafter be captured by our forces in any of the States embraced by the proclamation” to be punished as “criminals engaged in exciting servile insurrection”—for which the punishment was death.45

Davis was particularly incensed by the Union plan to recruit former slaves as soldiers. When a raid by Confederate troops on Union-occupied St. Catherines Island off the coast of Georgia in November 1862 captured six black soldiers, the commanding general telegraphed Richmond for instructions on what to do with them. The new secretary of war, James Seddon, consulted Davis, who told him to make the following reply: “They cannot be recognized in any way as soldiers subject to the rules of war and to trial by military courts. . . . Summary execution must therefore be inflicted on those taken.”46

Whether the six black men were actually executed is not known. And whether the Confederacy would carry out such a draconian policy remained to be seen. Perhaps the war would soon be over and the question would remain moot. Confederate victories at the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chickasaw Bluffs, and the drawn Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro), which Davis considered a victory, had produced demoralization in the North. The antiwar Copperhead movement mushroomed in strength, giving rise to hope in the South that the Lincoln administration would be forced to negotiate peace. Davis faced the new year with reviving confidence. “It is not possible,” he told Mississippians at the end of 1862, “that a war of the dimensions that this one has assumed, of proportions so gigantic, can be very long protracted. The combatants must be soon exhausted. But it is impossible, with a cause like ours, we can be the first to cry, ‘Hold, enough.’”47