4.

THE CLOUDS ARE DARK OVER US

In Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, the Battle of Murfreesboro produced bitter recriminations about missed opportunities that turned initial success into a retreat. After the Confederate attack on December 31 drove the enemy right back three miles, Union resistance stiffened and stopped the Southern onslaught. Bragg nevertheless telegraphed a report of victory to Richmond, where it caused “great exaltation.” He added that the enemy “is falling back.”1 But the enemy was not. Rejecting the advice of subordinates, Bragg ordered another attack on January 2, which was shredded by Union artillery on high ground across the Stones River. With supplies running short and Union reinforcements arriving, Bragg decided to withdraw south thirty miles to a new base at Tullahoma.

Twice in three months the Army of Tennessee had apparently snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. And twice Bragg and his senior generals blamed one another. So divisive and open did the contention become that Davis ordered Joseph Johnston to visit the army, “decide what the best interests of the service require, and give me the advice which I need at this juncture.”2 The disaffected generals led by Davis’s friend Leonidas Polk wanted Johnston to replace Bragg. Bragg himself hinted at a willingness to accept this solution.3

Davis had good reason to believe that Johnston would jump at the chance. He had continued to complain about his anomalous status as a theater commander with responsibility but no authority and to express a desire for a real army command. “I cannot help repining at this position,” which was “little, if any, better than being laid on the shelf,” he told Senator Louis T. Wigfall.4 With no chance of obtaining what he really “repined” for, a return to the Army of Northern Virginia, Johnston nevertheless refused to consider taking command of Bragg’s army. Instead, after inspecting the troops and talking with corps and division commanders, he reported to Davis that the army was in good shape and the disaffection was a tempest in a teapot that was subsiding. The army’s operations under Bragg “evince great vigor & skill,” Johnston assured Davis. “I can find no record of more effective fighting in modern battles than that of this army in december. . . . The interest of the service requires that General Bragg should not be removed,” especially after “he has just earned if not won the gratitude of the country.” Johnston refused to acknowledge that there might have been some reason why Bragg had not won that gratitude. In any event, Johnston insisted that he would be dishonored by accusations of conflict of interest if, after investigating the army’s condition, he were then to take command of it.5

A stickler for the fine points of honor himself, Davis nevertheless could not see how Johnston would violate that code by replacing Bragg. After all, Johnston’s original assignment as theater commander authorized him to take field command of any of the armies under his jurisdiction when the good of the service required it.6 Davis soon realized that Johnston’s report of reduced tensions within the army was inaccurate. The tempest did not subside. On March 9 the president had Secretary of War Seddon order Johnston to take over the army and send Bragg to Richmond for reassignment.7 But Johnston managed once again to avoid obedience to his commander in chief’s wishes. When he arrived at Tullahoma, Johnston learned that Bragg’s wife was seriously ill, so he could not be sent away. Then Johnston himself fell ill. On April 10 he reported that he was “not now able to serve in the field.”8 For weal or woe, Bragg would remain in command of the Army of Tennessee. And Davis’s main attention shifted to Virginia and Mississippi, where Union armies were once more on the move.

• • •

UNION MAJ. GEN. JOSEPH HOOKER LAUNCHED THE FOURTH “On to Richmond” campaign in April 1863. Outnumbering the Army of Northern Virginia by almost two to one (Longstreet was absent with two divisions on a separate campaign south of the James River), Hooker left part of his army at Fredericksburg and crossed the Rappahannock upriver with the rest to come in on Lee’s rear. The Confederate commander daringly divided his army, sent Jackson on a long march to attack the Union flank, caved it in, and drove the befuddled Hooker back across the river by May 6.

Although ill and abed, Davis was elated by this victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville. He sent official congratulations to Lee “and the troops under your command for this addition to the unprecedented series of great victories which your army has achieved,” although regretting “the good and the brave who are numbered among the killed and wounded.” The most important of these was Stonewall Jackson, who died on May 10 of pneumonia that set in after he was wounded by friendly fire at Chancellorsville. Nevertheless, Lee’s success caused Davis to hope that “we will destroy Hooker’s army and then perform that same operation on the army sent to sustain him.”9

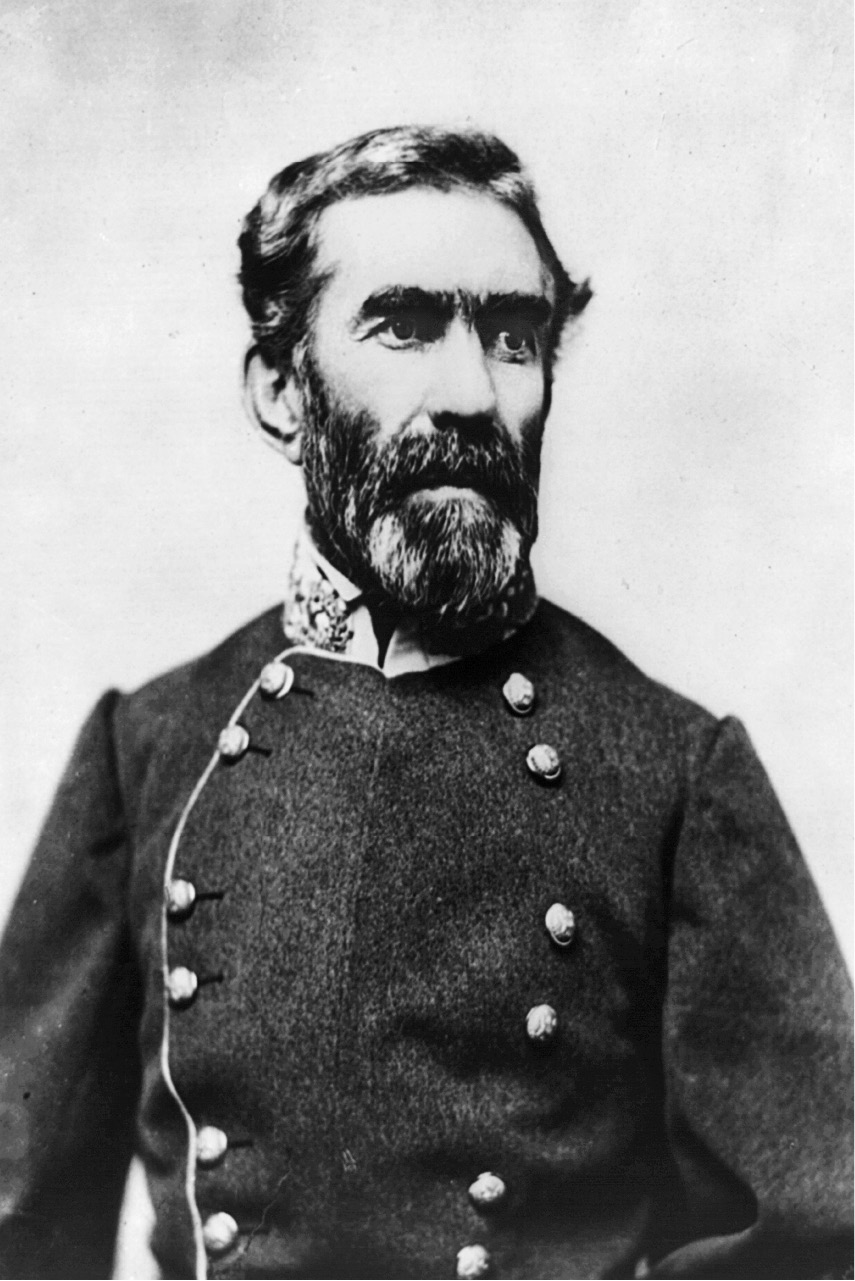

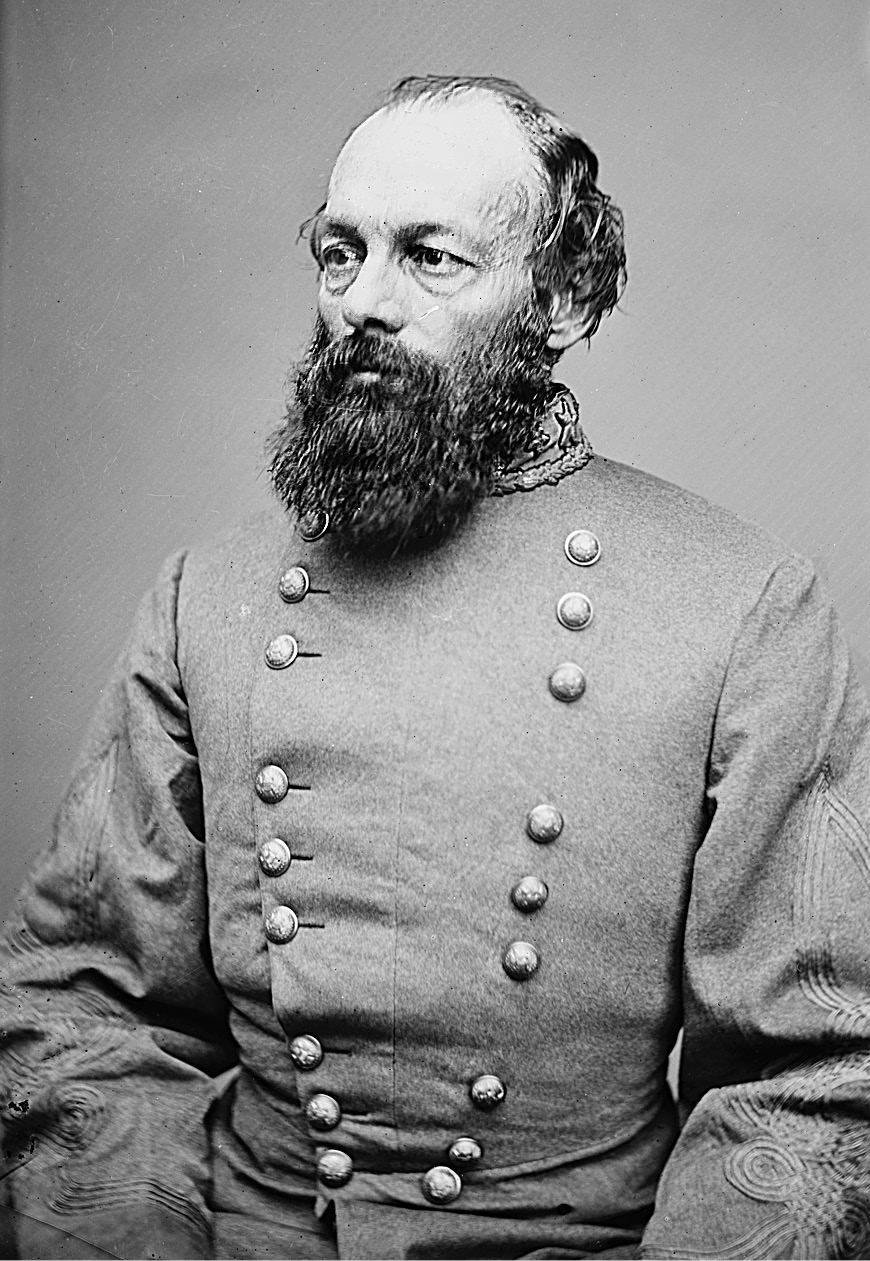

Braxton Bragg

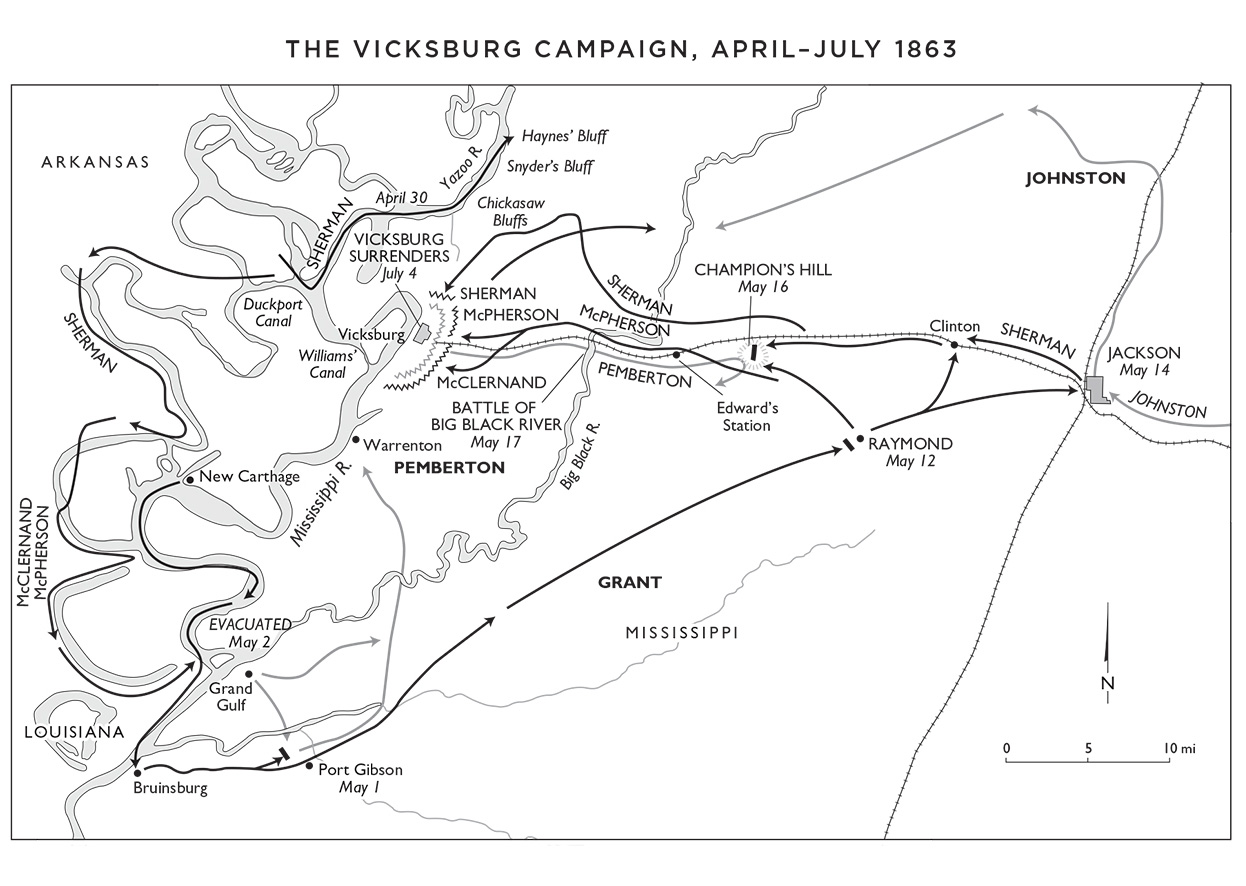

But ominous news arrived from Mississippi. Grant had crossed the river below Vicksburg and was advancing on that citadel, which constituted one of the last links between the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy, the other being Port Hudson two hundred river miles downstream. “To hold the Mississippi is vital,” Davis declared. Could Pemberton repeat his checkmate of the first Union attack in December? Davis initially hoped that cavalry raids on Grant’s supply line would stop him, as they had on the previous occasion.10 But Grant had cut loose from his communications and was living off the land this time. Concern mounted in Richmond as the news from Mississippi grew more grave in the second week of May.

With the front in Virginia apparently stabilized for the time being, several officials suggested sending detachments from Lee’s army to the West. Longstreet proposed to take the two divisions that had been operating south of the James to reinforce Bragg in Middle Tennessee. They could then undertake an offensive against Rosecrans that, if successful, might force Grant to loosen his grip in Mississippi. Secretary of War Seddon wanted to send these two divisions directly to Mississippi—nearly a thousand miles away. Lee opposed this idea vigorously, noting that Hooker still outnumbered his and was being reinforced, so that to weaken the Army of Northern Virginia by Longstreet’s continued absence “is hazardous, and it becomes a question between Virginia and Mississippi.”11

Lee proposed instead to reincorporate Longstreet’s divisions into the Army of Northern Virginia. With additional reinforcements he would then invade Pennsylvania, where he hoped to win another battle on the scale of Chancellorsville. A successful invasion might drain troops away from both Rosecrans and Grant. It would strengthen the antiwar Northern Copperheads, who might force the Lincoln administration into peace negotiations. Lee came personally to Richmond for meetings with Davis and his cabinet on May 15 and 16. The president had been ill for the past month with inflammation of the throat and a recurrence of severe neuralgia, which threatened the sight of his remaining good eye. For several weeks he had been too weak to come into the office, but he had continued to work from his sickbed in the executive mansion. He roused himself for these conferences, where he wavered between the options of reinforcing Pemberton or invading Pennsylvania. But in the long discussions of these alternatives, Lee carried the day with Davis and most of the cabinet. Postmaster General John Reagan held out for the option of sending Longstreet to Vicksburg. He was from Texas and feared that the loss of the Mississippi River would doom the Confederacy. Davis shared that concern, but so strong was his confidence in Lee that he approved the invasion of Pennsylvania and planned to reinforce Pemberton from other sources.12

This decision did not mean that Davis thought the Eastern theater was more important than Mississippi. Both were crucial; and because his home (partly destroyed by Union forces) was in Mississippi, he remained preoccupied with that theater. Ordnance Chief Josiah Gorgas wrote in his diary after a conversation with the president in March 1863 that he was “wholly devoted to the defense of the Mississippi, and thinks and talks of little else.”13 After the repulse of the Union navy’s attack on the Charleston defenses on April 7, Davis ordered five thousand men from South Carolina to Mississippi. He scraped together a few thousand from elsewhere, and on May 9 he had Seddon order Johnston to Mississippi to take personal command of Confederate troops there. Johnston arrived at Jackson on May 13 to find that Grant’s army was about to capture the state capital and was preparing to turn west toward Vicksburg itself. “I am too late,” Johnston wired Richmond.14

This pessimism set the tone for Johnston’s efforts—or lack thereof—during the next seven weeks. He ordered Pemberton to evacuate Vicksburg and combine his army with Johnston’s small corps to form a mobile force to defeat Grant, after which they could reoccupy Vicksburg. Pemberton was reluctant to do so because Davis had telegraphed him a week earlier that “to hold both Vicksburg and Port Hudson is necessary to our connection with Trans-Mississippi.” Many Southerners were already skeptical of Pemberton because he was a Yankee. He feared that if he obeyed Johnston’s instructions to abandon Vicksburg, he would be accused of treason.15

In any event, Grant’s victories over most of Pemberton’s army at Champion’s Hill on May 16 and Big Black River on May 17 made the question moot. Pemberton’s remaining troops were driven back into the Vicksburg defenses, where they repulsed Union attacks on May 19 and 22. Grant settled in for a siege, while Davis continued to send dribs and drabs of reinforcements to Johnston and to urge him to break through Grant’s tightening cordon. Persistent illness added to Davis’s frustration, and stress in turn no doubt worsened his health. Almost daily he sent telegrams to Johnston imploring him to do something, messages to Bragg asking if he could spare reinforcements for Johnston, and missives to Governor John Pettus asking him to organize state militia to join Johnston.16

Little came of these efforts: Bragg could not send any more men without jeopardizing his own position at Tullahoma; Pettus had already scraped the bottom of the militia barrel; and from Johnston came very little information except that the 23,000 troops he had patched together were too few to attack the 30,000 under Sherman that Grant had put in place to protect the rear of his 40,000 besieging Pemberton’s 30,000 at Vicksburg. Davis believed that Johnston had 31,000 men; the actual number of effectives was probably fewer, but more than the 23,000 Johnston claimed.17

In Vicksburg the hope that Johnston would rescue them buoyed both soldiers and civilians. “We are certainly in a critical condition,” wrote an army surgeon in his diary, but “we can hold out until Johnston arrives with reinforcements and attacks the Yankees in the rear.” Round-the-clock artillery fire from Grant’s batteries on land and navy gunboats on the river drove Southern civilians and soldiers alike into caves carved from the soft loess soil, where they waited for rescue. The Vicksburg newspaper—now being printed on wallpaper—reported that “the undaunted Johnston is at hand. . . . Hold out a few days longer, and our lines will be opened, the enemy driven away, the siege raised.”18

But Johnston was daunted, and he was not at hand. On June 15 he wired Secretary of War Seddon: “I consider saving Vicksburg hopeless.” A War Department official reported that Davis was “furious with Johnston.” He directed Seddon to reply: “Your telegram grieves and alarms us. Vicksburg must not be lost, at least without a struggle. The interest and honor of the Confederacy forbid it. I rely on you still to avert the loss. If better resource does not offer, you must hazard attack.”19

But Johnston did not hazard attack. On the verge of starvation, the thirty thousand soldiers and three thousand civilians still in Vicksburg were surrendered on the Fourth of July. When the news reached Richmond, Davis was “bitter against Johnston,” according to Ordnance Chief Josiah Gorgas. “When I said that Vicksburg fell apparently from want alone of provisions, he remarked ‘Yes, from want of provisions inside and a general outside who wouldn’t fight.’”20

Johnston retreated to Jackson; Sherman pursued and began to surround the city. Hoping to salvage something from “the disastrous termination of the siege of Vicksburg,” Davis urged Johnston to hold the state capital if possible. “The importance of your position is apparent, and you will not fail to employ all available means to ensure success.” But Johnston feared encirclement by Sherman’s force, so he evacuated Jackson on July 16. He left so hastily that he failed to secure some four hundred railroad cars and locomotives, which the Confederacy would sorely miss.21

With the fall of Vicksburg, Port Hudson became untenable and surrendered on July 9. The Confederacy was cut in two: “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea” were Lincoln’s felicitous words. Davis was profoundly depressed by these events. “Your letter found me in the depth of gloom in which the disasters on the Mississippi have shrouded our cause,” he wrote to a friend in mid-July. “The clouds are truly dark over us.” But they could not think of giving up. “Can any one not fit to be a slave, and ready to become one, think of passing under the yoke of such as the Yankees have shown themselves to be by their conduct in this war?” he remonstrated. The “sacrifices of our people have been very heavy of both blood and treasure . . . but the prize for which we strive, freedom and independence, is worth whatever it may cost.”22

Davis relieved Johnston of his theater command, making Bragg independent of him and leaving Johnston in control only of the troops he had evacuated from Jackson. Davis also wrote a fifteen-page letter in his own hand charging Johnston with what amounted to dereliction of duty in the Vicksburg campaign. Johnston replied, heatedly denying the charge. This exchange inaugurated what Johnston’s biographer describes as “a paper war” between the partisans of the two men. Johnston’s ally in Congress, Senator Louis T. Wigfall, called for publication of all the correspondence related to the campaign. Once an ally and confidant of Davis’s, Wigfall had become one of his sharpest critics. He hoped to mine these documents for evidence to embarrass Davis and place the blame on Pemberton.23

Pemberton’s hundred-page report, not surprisingly, blamed Johnston. Someone in the Davis administration leaked portions of it to the Richmond Sentinel, a pro-administration paper that made its position clear: “With an army larger than won the first battle of Manassas,” Johnston “made not a motion, he struck not a blow, for the relief of Vicksburg. For nearly seven weeks he sat down in sound of the conflict, and he fired not a gun. . . . He has done no more than to sit by and see Vicksburg fall, and send us the news.” Not to be outdone, someone on Johnston’s staff apparently leaked a letter written by his medical officer that praised Johnston and excoriated Pemberton. This letter was published by several newspapers and inspired a vendetta against the general, who was all the more vulnerable because of his Pennsylvania birth.24

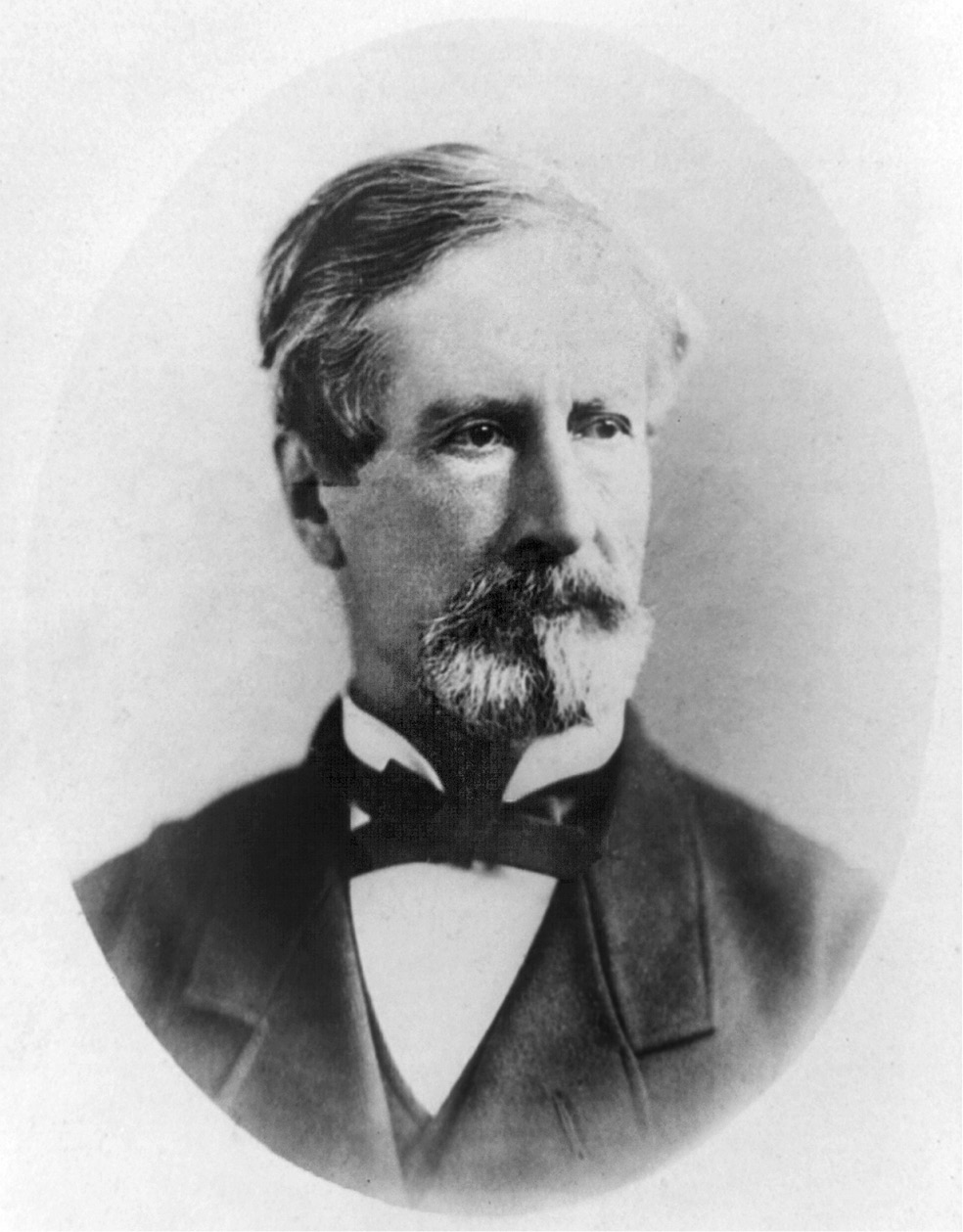

J. C. Pemberton

Davis regarded these attacks on Pemberton as an attack on himself. He continued to defend the general against the growing opprobrium from all corners of the Confederacy. One newspaper quoted the president (perhaps not with literal accuracy) as stating, “My confidence in General Pemberton has not abated in the least—he is one of the most gallant and skillful generals in the service.”25 Public sentiment and army opinion turned against Davis on this issue, however. Two friendly Mississippi congressmen warned him that Pemberton “has entirely lost the confidence of the country.” Davis failed to understand “the unhappy, disaffected, dangerous sentiment which pervades the whole people” on this matter. “You cannot uphold him. The attempt will only destroy you.”26

Davis’s opponents in Congress and the press did indeed use the Johnston-Pemberton controversy to undermine him. The vitriolic pen of John Moncure Daniel, editor of the Richmond Examiner, lashed out at Davis’s “flagrant mismanagement.” From “the frigid heights of an infallible egotism . . . wrapped in sublime self-complacency,” Davis “has alienated the hearts of the people by his stubborn follies” and “his chronic hallucinations that he is a great military genius.” Davis “prides himself on never changing his mind; and popular clamor against those who possess his favor only knits him more stubbornly to them. . . . Had the people dreamed that Mr. Davis would carry all his chronic antipathies, his bitter prejudices, his puerile partialities into the presidential chair, they would never have allowed him to fill it.”27

The poison of this conflict seeped into the body politic of the Confederacy. Three months after the fall of Vicksburg, Mary Chesnut wrote in her diary that her husband, a member of Davis’s staff, told the president after an inspection trip “that every honest man he saw out west thought well of Joe Johnston. He knows that the president detests Joe Johnston for all the trouble he has given him. And General Joe returns the compliment with compound interest. His hatred of Jeff Davis amounts to a religion.”28

• • •

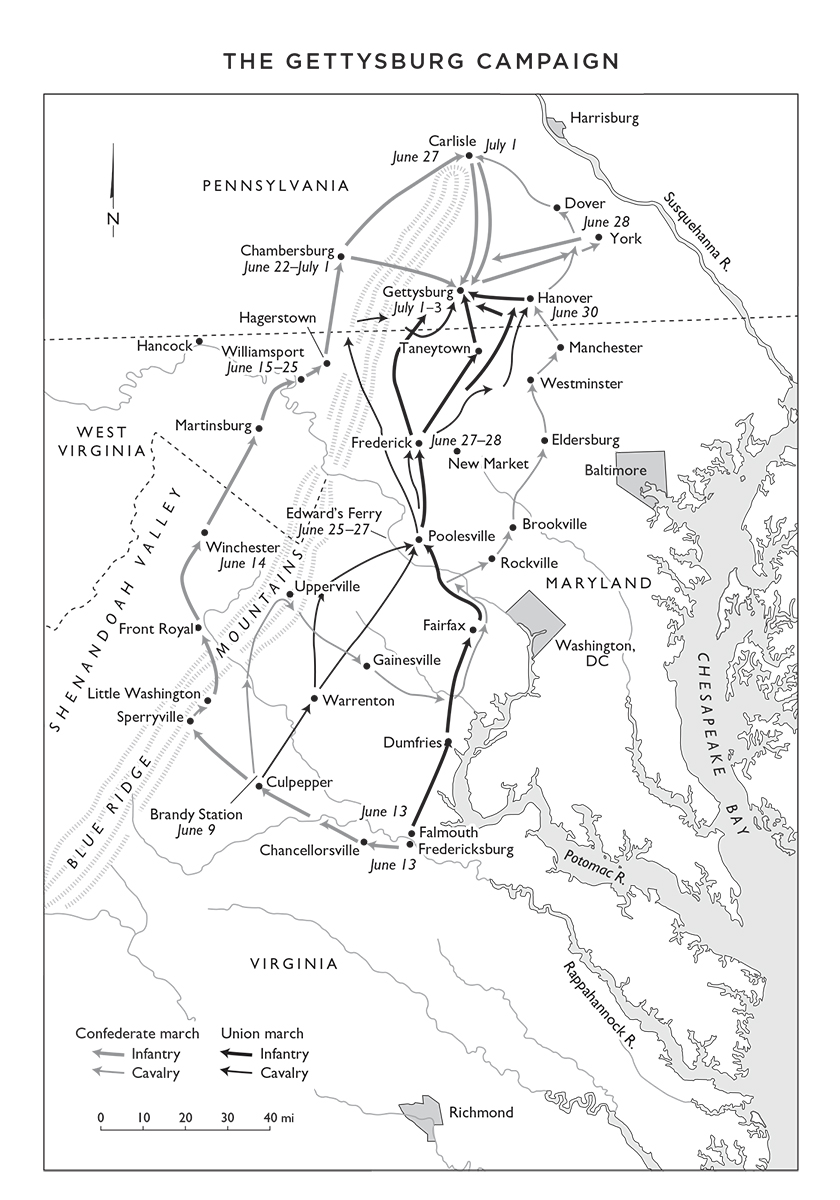

IF DAVIS HAD NOT PREVIOUSLY GRASPED THE TRUISM THAT when things go wrong in wartime the chief blame will fall on the commander in chief, he certainly realized it now. He was also taking heat for the defeat at Gettysburg and for setbacks in Tennessee and Arkansas. Most disappointing was Lee’s retreat from Pennsylvania after a failed campaign that left more than a third of his army killed, wounded, or captured.

Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania had started with great promise. With seventy-five thousand men he swept northward through the Shenandoah Valley, scattered the Union garrison at Winchester and captured almost four thousand of them, and moved into Pennsylvania during the third week of June. Confederate quartermasters gathered thousands of horses, cattle, and hogs and tons of other supplies from Pennsylvania farms. The army also captured scores of black people; claiming they were escaped slaves (many had actually been born in Pennsylvania), officers sent them back to Virginia and slavery. Initial reports of success that reached Richmond caused exultation. Even the Examiner praised “the present movement of General Lee,” which “will be of infinite value as disclosing the . . . easy susceptibility of the North to invasion. . . . Not even the Chinese are less prepared by previous habits of life and education for martial resistance than the Yankees. . . . We can carry our armies far into the enemy’s country, exacting peace by blows leveled at his vitals.”29

Lee thought so too. His reading of Northern newspapers had convinced him that “the rising peace party of the North,” as he described the Copperheads, offered the Confederacy a “means of dividing and weakening our enemies.” It was true, Lee acknowledged in a letter to Davis on June 10 as the army started north, that the Copperheads professed to favor reunion as the object of the peace negotiations they were urging, while the Confederate goal in any such parley would be independence. But it would do no harm, Lee advised Davis, to play along with such reunion sentiment to weaken Northern support for the war, which “after all is what we are interested in bringing about. When peace is proposed to us it will be time enough to discuss its terms, and it is not the part of prudence to spurn the proposition in advance, merely because those who made it believe, or affect to believe, that it will result in bringing us back to the Union.”30

Lee concluded his letter with a broad hint that Davis “will best know how to give effect” to these views. Davis did indeed think he knew a way to offer the olive branch of a victorious peace at the same time that Lee’s sword was striking Northern vitals. Not long after he received Lee’s letter, Davis also read one from Vice President Alexander H. Stephens suggesting a mission to Washington under a flag of truce to meet with his congressional colleague and friend from an earlier time, Abraham Lincoln. The ostensible purpose would be a negotiation to renew the cartel for prisoner-of-war exchanges, which had broken down because of the Confederate threat to execute the officers and reenslave the men of black Union regiments. But Stephens suggested that if Lincoln agreed to receive him, he could also propose “a general adjustment” to end the war on the basis of a Northern agreement to recognize the “Sovereignty of [a state] to determine its own destiny.” Davis immediately summoned Stephens from Georgia to undertake the mission by joining Lee in Pennsylvania and looking for an opening to proceed to Washington.31

Stephens had not previously known about Lee’s invasion. He protested that the Union government would never receive him while an enemy army was on Northern soil. On the contrary, said Davis; that was precisely the time to negotiate from a position of strength that would force concessions from the Lincoln administration. The cabinet backed Davis, so Stephens reluctantly agreed to go. It was too late to catch up with Lee in Pennsylvania, so Stephens headed down the James River under a flag of truce to Union lines at Fort Monroe, where he arrived on July 2 and had word sent to Lincoln requesting a pass to come to Washington.32

While this effort was being planned, Lee tried to pry as many troops out of the Carolinas as he could to strengthen his invasion force. Davis did order three brigades from North Carolina to join Lee. But he denied the general’s request for a large number of Beauregard’s troops from South Carolina, plus Beauregard himself, to come to Virginia as a diversionary threat to occupy Union forces that would otherwise confront Lee in Pennsylvania. Davis had already sent two of Beauregard’s brigades to Johnston in Mississippi, and renewed Federal operations against Charleston made it impossible to strip its defenses any more. Lee also urged that some of the troops defending Richmond be added to his invasion force. But threatening movements against the capital by the small Union army on the peninsula forced Davis regretfully to refuse this request. “It has been an effort with me,” the president told Lee, “to answer the clamor to have troops [already sent] stopped or recalled to protect the city.”33

Whether any of these requested reinforcements would have enabled Lee to win the Battle of Gettysburg is impossible to say. After three days of repeated attacks that cost the Army of Northern Virginia at least twenty-four thousand casualties, the Confederates began their nightmare retreat from Gettysburg in a drenching rainstorm on July 4 at almost the same hour that Pemberton surrendered thirty thousand men to Grant at Vicksburg. Alexander Stephens’s message asking for a pass to see Lincoln in Washington also arrived in the U.S. capital on July 4. Having just learned the news from Gettysburg, Lincoln replied curtly that Stephens’s request was “inadmissible.”34

The defeat at Gettysburg did not impair Davis’s confidence in Lee—in sharp contrast with his loss of what little faith he had left in Johnston. In late July Davis wrote to Lee, “I have felt more than ever the want of your advice during the recent period of disaster.” Louis Wigfall reported that Davis was “almost frantic with rage if the slightest doubt was expressed as to [Lee’s] capacity and conduct. . . . He was at the same time denouncing Johnston in the most violent . . . manner & attributing the fall of Vicksburg to him and him alone.”35

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Confederate dead gathered for burial at the edge of the Rose Woods, July 5, 1863

Some newspapers, especially the Charleston Mercury, did express more than slight doubts about Lee’s capacity and conduct in the Gettysburg campaign. Perhaps stung by this criticism, and experiencing health problems, Lee offered his resignation in a letter to Davis on August 8. “I cannot even accomplish what I myself desire,” wrote the general. “How can I fulfill the expectations of others?” Without naming anyone, Lee stated that “a younger and abler man than myself can readily be attained” for the command. “My dear friend,” Davis replied. “There has been nothing which I have found to require a greater effort of patience than to bear the criticisms of the ignorant,” so he could empathize with Lee’s feelings. But “to ask me to substitute you by someone in my judgment more fit to command, or one who would possess more of the confidence of the army, or of the reflecting men in the country is to demand an impossibility. . . . Our country could not bear to lose you.”36

Yet another defeat on the Fourth of July added to the Southern cup of woe. Unaware of the surrender at Vicksburg, the Confederate commander in Arkansas, Theophilus Holmes, ordered an attack that day on the Union garrison at Helena as a diversion to aid Pemberton. The defenders easily repelled the assault, inflicting six times as many casualties on the attackers as they suffered themselves. This victory opened Arkansas to a Union offensive that captured Little Rock on September 10.

The situation in Arkansas had been a headache for Davis ever since he had promoted his West Point classmate Holmes to lieutenant general and appointed him commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department in 1862. Davis had a higher regard for Holmes’s abilities than almost anyone else in the Confederacy—including Holmes himself. Complaints from Arkansas political leaders and Confederate Missourians about the general’s incompetence scarcely dented Davis’s confidence in him. One Missourian denounced the president as someone “who stubbornly refuses to hear or regard the universal voice of the people.” Davis did go so far as to replace Holmes with Edmund Kirby Smith as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department in February 1863. But he kept Holmes in place as head of the subdistrict of Arkansas. “I have an abiding faith that under the blessing of Providence, you will yet convince all fair minded men, as well of your zeal and ability, as of your integrity and patriotism,” Davis told Holmes.37 But Davis convinced no one, and he finally yielded to Kirby Smith’s recommendation in March 1864 that Maj. Gen. Sterling Price replace Holmes.

Edmund Kirby Smith

After the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, the Union navy patrolled the whole length of the Mississippi River. Gunboats effectively sealed off the two parts of the Confederacy from each other. Communications between Richmond and General Kirby Smith took weeks via a roundabout route by blockade runner through Galveston or even Matamoros, Mexico, or by smuggling across the Mississippi at night. Kirby Smith became the head of a semi-independent fiefdom with quasi-dictatorial powers. He maintained good relations with the governors of Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas (the latter two in temporary state capitals because Baton Rouge and Little Rock were occupied by the enemy). He established mines, factories, shipyards, and other facilities to supply and carry out military operations separate from those in the rest of the Confederacy, financed by cotton exports through Matamoros. “As far as the constitution permits,” Davis told Kirby Smith, “full authority has been given to you to administer to the wants of Your Dept., civil as well as military.”38 In effect, Kirby Smith rather than Davis became commander in chief of the Trans-Mississippi theater. For the next two years “Kirby Smith’s Confederacy” fought its own war pretty much independently of what was happening elsewhere.39

• • •

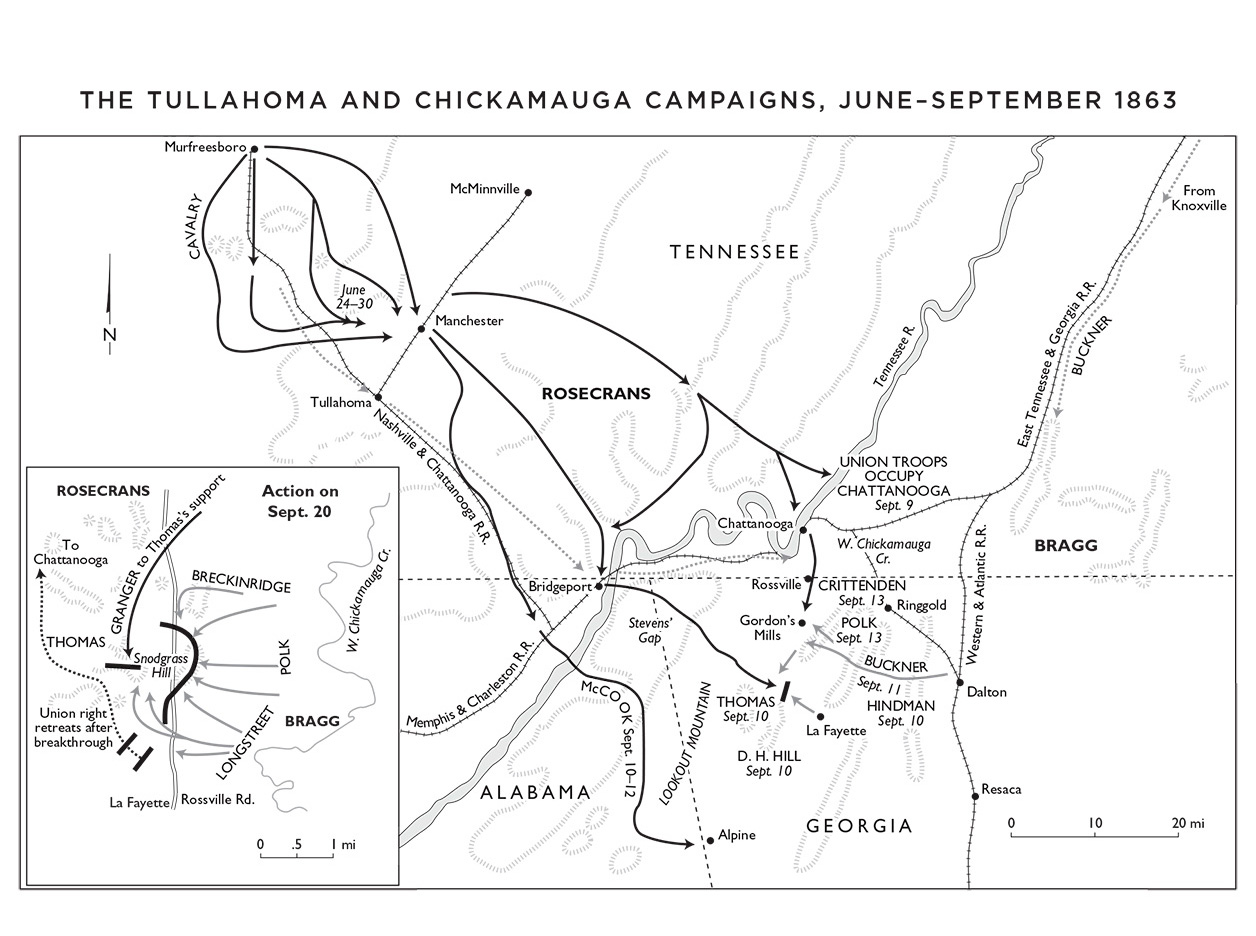

DESPITE ALL HIS OTHER PROBLEMS IN 1863, DAVIS’S BIGGEST command headache remained Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee. For almost five months after the Battle of Murfreesboro, this army and General William S. Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland had licked their wounds and confronted each other twenty miles apart. Neither army undertook any major initiatives except cavalry raids on each other’s communications. Bragg held a strong defensive position behind four gaps in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains. In the last week of June 1863, Rosecrans, after much prodding by Lincoln, finally began an offensive. Feinting toward the western gaps, he moved so swiftly through the others that the Confederates were flanked or knocked aside almost before they knew what had hit them. A Union brigade of mounted infantry armed with Spencer repeating rifles penetrated deeply behind the Confederate position and threatened to cut Bragg’s rail lifeline, forcing him to retreat all the way to Chattanooga by July 3. In little more than a week, the Confederacy lost control of Middle Tennessee—the same week that climaxed with the Battle of Gettysburg and the surrender of Vicksburg.

Bragg was unwell during this lightning campaign, and several of his principal subordinates performed poorly—especially Leonidas Polk and William Hardee. The same two renewed the backroom intrigues against Bragg that had long plagued this dysfunctional army.40 The infighting could not have come at a worse time. The Confederate grip on Chattanooga appeared endangered. The city had great strategic importance. It was located at the junction of the Confederacy’s two east-west railroads and formed the gateway to the war industries of Georgia. Having already split the Confederacy in two with the capture of Vicksburg, Northern armies could split it almost in three by a penetration into Georgia via Chattanooga. In mid-August Rosecrans began a new advance with the intention of doing just that.

Davis was fully alive to the significance of this threat. He instructed Johnston to send nine thousand troops to Bragg from his idle army in Mississippi. On August 24 the president summoned Lee to Richmond for extended consultations. The front in Virginia was quiet, and Davis asked Lee if he would be willing to go to Chattanooga and take command of the Army of Tennessee. Lee demurred; Davis did not press the issue. Longstreet proposed that he take two divisions of his corps to reinforce Bragg. Lee initially opposed this plan as well. In a reprise of his argument before the invasion of Pennsylvania, he suggested that an offensive against the Federals in Virginia would relieve the pressure on Bragg. Davis leaned toward approval, but then changed his mind. Instead, he secured Lee’s reluctant acceptance of the detachment of Longstreet. On September 7 Lee returned to his headquarters and set that process in motion.41

Events in Tennessee moved so quickly that it appeared Longstreet would not get there in time. Rosecrans feinted a crossing of the Tennessee River above Chattanooga but instead went across at several places below the city. As his troops moved through mountain passes toward the railroad that connected Chattanooga and Atlanta, Bragg evacuated Chattanooga on September 9. But then the Confederate general reached into his bag of tricks. He sent fake deserters into Union lines with planted stories of Confederate demoralization and headlong retreat. Rosecrans swallowed the bait. He sent each of his three corps through separate mountain gaps beyond supporting distance of one another to cut off the supposed retreat. Bragg intended to trap fragments of the enemy’s separated forces and defeat them in detail. So corrosive were the relationships among Bragg and several of his corps and division commanders, however, that the effort broke down. Three times from September 10 to 13 Bragg ordered various subordinates to attack an isolated enemy corps or division; three times they found reasons to disobey Bragg’s distrusted orders. Belatedly recognizing the danger, Rosecrans consolidated his army, and Bragg’s “golden opportunity” to defeat the enemy in detail was gone.42

With the arrival of Longstreet’s divisions beginning on September 18, the Confederates would have a rare numerical superiority over the Federals. Crossing Chickamauga Creek a dozen miles south of Chattanooga, Bragg launched an attack on September 19 in an attempt to cut the enemy off from their base in the city. The results that day were indecisive. Longstreet arrived that night with the rest of his troops. Bragg gave him command of the army’s left wing and Polk the right. He ordered Polk to attack at dawn, leading with Lt. Gen. D. H. Hill’s corps. Longstreet’s wing was to go forward once Polk’s assault was in full stride. Dawn came, but no attack. As the hours ticked by, it became clear that the army’s command system had again foundered. Polk and Hill seemed to act with little urgency; only Bragg’s personal supervision got the attack started—four hours late. Because of a mixup in orders on the Union side, however, Longstreet’s advance encountered a gap in the enemy line and broke through, sending one-third of Rosecrans’s army—including Rosecrans himself—fleeing to the rear. Only the determined stand by the remainder, under Maj. Gen. George Thomas, prevented a complete Union collapse. That night the Federals pulled back to Chattanooga.

Despite the bungling, Bragg had won what appeared to be a remarkable victory. The news elated Richmond. The War Department clerk John B. Jones wrote in his diary that “the effects of this great victory will be electrical. The whole South will be filled again with patriotic fervor, and in the North there will be a corresponding depression. . . . Surely the Government of the United States must now see the impossibility of subjugating the Southern people, spread over such a vast extent of territory.”43

This optimism turned out to be wishful thinking. The Army of the Cumberland still held Chattanooga. The Battle of Chickamauga had cost the Confederates heavy casualties, so instead of renewing the attack Bragg settled down for a siege, hoping to starve the Yankees out. Instead of caving in, however, the United States government redoubled its efforts. Washington sent twenty thousand men from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce Rosecrans. It also sent Grant to Chattanooga. He replaced the discomfited Rosecrans with George Thomas, opened a new supply line, and summoned Sherman to Chattanooga with four more divisions. The Federals were clearly preparing a counteroffensive to reverse the results of Chickamauga and drive the Confederates deep into Georgia.

While these preparations went forward, renewed internecine warfare racked the Army of Tennessee’s officer corps. Bragg demanded an explanation from Polk for the delay in his attack on September 20. Before replying, Polk met with Hill and Longstreet and concluded that Bragg should be removed from command. Polk wrote to Davis that Bragg must go. He even had the effrontery, in view of his own culpability, to claim that Bragg had the enemy “twice at his mercy, and has allowed it to escape both times.”44

Meanwhile, Polk responded to Bragg’s request for an explanation of his tardy attack by shifting the blame to D. H. Hill. Bragg considered this reply specious, and suspended Polk from command of his corps. He explained to Davis that although Polk was “gallant and patriotic,” he was “luxurious in his habits, rises late, moves slowly, and always conceives his plans the best—He has proved an injury to us on every field where I have been associated with him.” Davis telegraphed Bragg deprecating his action against Polk. The president was torn between his sympathy for Bragg and his long friendship with Polk, which caused Davis to estimate the latter’s military acumen too highly. He resolved his conflicting feelings by telling Bragg that Polk should be restored to his post in order to avoid “a controversy which could not heal the injury sustained” and “would entail further evil. . . . The opposition to you both in the army and out of it has been a public calamity in so far as it impairs your capacity for usefulness.”45

Before Bragg received this letter, ten generals and a colonel in the Army of Tennessee, including corps commanders Longstreet, Hill, and Simon B. Buckner, signed a petition to Davis calling for Bragg’s removal. “Whatever may have been accomplished heretofore, it is certain that the fruits of the victory of Chickamauga have now exceeded our grasp,” the petition stated. Bragg’s personality “totally unfits him” for command. If he remained, the signers “can render you no assurance of the success which your Excellency may reasonably expect.”46

James Longstreet

Before he saw this petition, Davis had concluded that he must make the long trip to Tennessee to deal personally with the imbroglio. He stopped first in Atlanta to meet with Polk. The general asked for a court of inquiry, which he believed would exonerate him. Davis wanted no such exhibition of the army’s dirty laundry. He decided to transfer Polk to Mississippi to serve with the remnant of Johnston’s army. Davis then visited Bragg’s headquarters at Marietta, Georgia. Bragg offered to resign—may even have urged Davis to accept his resignation to resolve the discord. But Davis rejected this idea. The logical replacement for Bragg would have been Beauregard or Johnston. Davis wanted no part of either. Instead, he hoped that he could persuade the malcontents to put aside their prejudices and act together for the good of the cause.

Davis held a meeting with Longstreet, Hill, Buckner, and Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham (who had taken over Polk’s corps). Bragg was also present. Contrary to Davis’s hopes for harmony, the generals one after another (starting with Longstreet) expressed their lack of confidence in Bragg. Davis was startled, and Bragg must have been mortified. The president may have suspected that Longstreet was angling for the command, and was offended by his forwardness. In any event, despite this clear evidence of disaffection, Davis decided that “no change for the better could be made,” and kept Bragg in command.47

Davis had brought John C. Pemberton with him from Richmond, apparently with the idea of giving him a corps under Bragg. But he changed his mind when he discovered that such an appointment would probably provoke a mutiny in the army. (Pemberton subsequently resigned his lieutenant generalship and loyally accepted an assignment as lieutenant colonel of artillery in the Richmond defenses.) Davis authorized Bragg to relieve Hill of corps command and to demote Buckner to division command. Bragg also reorganized other divisions and brigades in an effort to minimize dissension. Longstreet eventually took his two divisions on what turned out to be a failed campaign to drive the Federals out of Knoxville, which they had occupied since early September.48

With these departures and reorganizations, Davis and Bragg hoped for a de-escalation of the army’s internal strife. The president urged Bragg to put the whole painful experience behind him and work with his subordinates toward a common goal despite lingering personal animosity. Davis’s own military experience had convinced him, he told Bragg, that it was not “necessary that there should be kind personal relations between officers to secure their effective co-operation in all which is official.” The recent crisis “should lift men above all personal considerations and devote them wholly to their country’s cause.”49

Davis continued his trip through the Deep South after leaving Bragg. He traveled to Alabama, Mississippi, back to Georgia, and then to South Carolina. He visited several towns and cities where he consulted with political leaders and military commanders, toured defenses, and gave public speeches praising troops from those areas, urging audiences to renew their efforts for victory, and predicting success for these efforts. He finally headed for home through North Carolina and arrived in Richmond on November 7, a month and a day after he had departed.50

Back in the capital the observant War Department clerk John Jones noted that Davis’s decision to retain Bragg in command “in spite of the tremendous prejudice against him in and out of the army” was extremely unpopular. “Unless Gen. Bragg does something more for the cause before Congress meets a month hence, we shall have more clamor against the government than ever.”51

Bad news followed Davis to Richmond. A Confederate attempt to capture the reopened Union supply line across the Tennessee River below Lookout Mountain was a fiasco. Grant continued to build up a powerful force in Chattanooga. On November 24 he struck. Northern troops under Joseph Hooker (who had come south with the reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac) drove the Confederates off Lookout Mountain. The next day George Thomas’s soldiers in the Army of the Cumberland broke through the main Confederate line on Missionary Ridge with an attack that seemed to have no chance to succeed—until it did. The demoralized soldiers of the Army of Tennessee fled in panic, defying all of Bragg’s efforts to stop them. Most of them did not stop until they reached Ringgold, Georgia, fifteen miles to the south.

The position where the breakthrough occurred was held mainly by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s corps. His dispositions were faulty and he appeared to have been drunk during the battle. Nevertheless, the chief blame came to rest as usual on Bragg’s slumping shoulders. The general manfully accepted responsibility. “The disaster admits of no palliation,” he told Davis, “and is justly disparaging to me as a commander.” But the cabal against him must share the blame, he added. “I fear we both erred in the conclusion for me to retain command here after the clamor raised against me—The warfare has been carried on successfully, and the fruits are bitter.” Bragg submitted his resignation; this time Davis promptly accepted it and appointed William Hardee as his successor.52

Public condemnation did not stop with Bragg; it went right up to the top. The fire-eating secessionist Edmund Ruffin declared that “the President is the first and main cause of this great disaster and panic, by his obstinately retaining Gen. Bragg in command.” A North Carolina woman whose diary revealed close attention to wartime events had been a supporter of Davis until now. But “it is sad to myself to realize how my admiration has lessened for Mr. Davis,” she wrote in December 1863, “since the loss of Vicksburg, a calamity brought on us by his obstinacy in retaining Pemberton in command, & now still further diminished by his indomitable pride of opinion in upholding Bragg.”53

Davis had no time for regrets. He had to find a new commander for the Confederacy’s second most important army, for Hardee had turned down the post because he did not feel up to the task of leading that troubled organization. The president again tried to persuade Lee to take the job. Lee responded that he would go “if ordered,” but made clear his preference to remain where he was. He suggested Beauregard, but that officer remained in Davis’s bad graces. The president asked Lee to come to Richmond “for full conference” on the problem. Lee assumed that Davis intended to order him to Georgia. If so, Lee talked him out of it. Instead, he urged Davis to appoint Joseph Johnston, even though Lee was fully aware of the president’s distaste for the prospect. Similar pressures in support of Johnston came from Congress, from several high-ranking officers including Polk and Hardee, and from Secretary of War Seddon. Most other cabinet members shared Davis’s distrust of Johnston’s capacity. But the president finally recognized that he had no alternative. On December 16 he ordered Johnston to take command.54 The die was cast; only time would tell if it would prove to be true metal.