7.

THE LAST RESORT

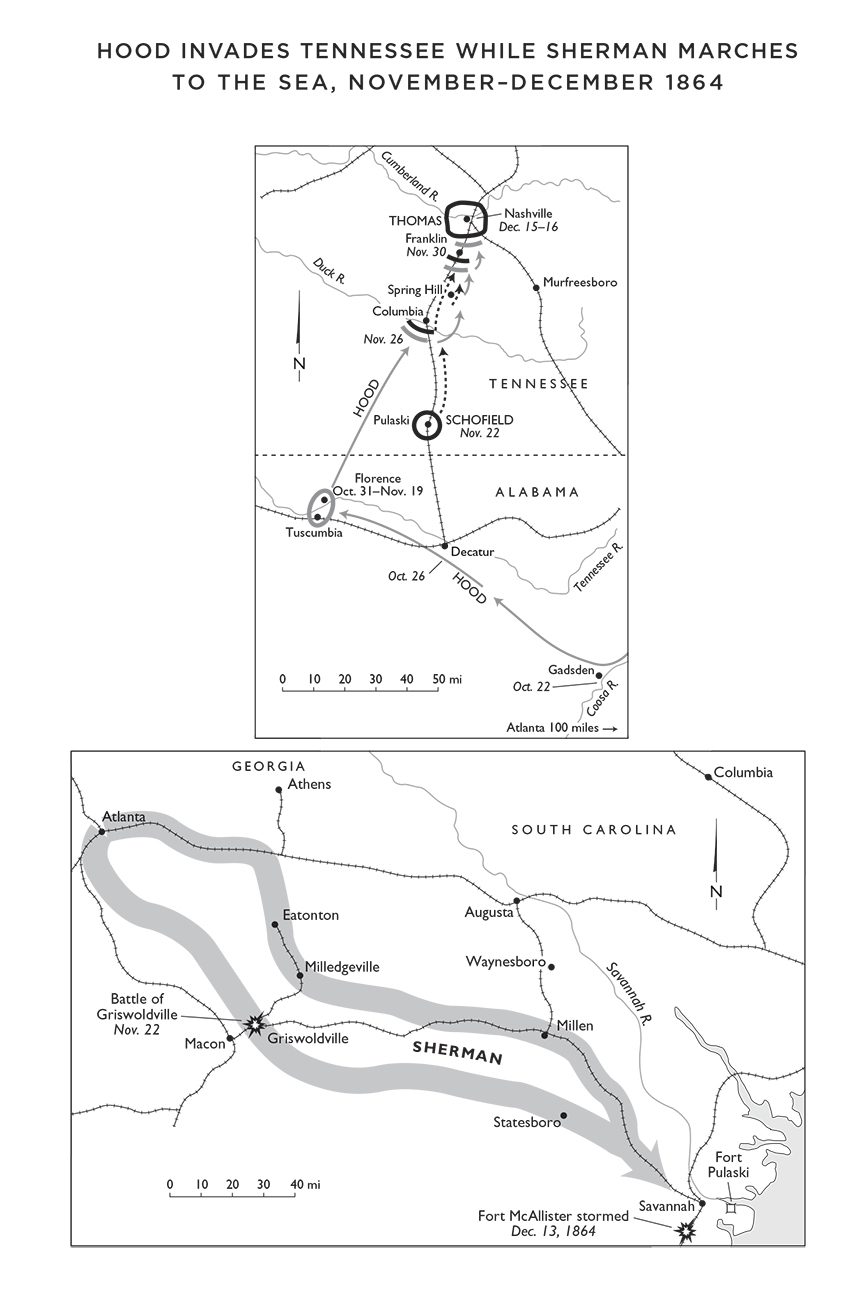

As Sherman departed Atlanta southward in the third week of November, Hood turned his back and began to move north into Tennessee. This action was contrary to the strategy agreed upon by Davis and Hood in their meeting at Hood’s headquarters on September 25, which required Hood to follow on Sherman’s heels if the Yankees moved south. But Davis’s public speeches during his trip to the Deep South had alluded to an invasion that would take Hood’s army all the way to the Ohio River. And in a letter to Hood on November 7, Davis seemed to endorse the general’s intention to do just that. An invasion of Tennessee was consistent with the president’s continued commitment to an offensive-defensive strategy, even though the Confederacy’s waning resources made such a strategy totally unrealistic.1

Hood’s campaign in Tennessee ended disastrously. In the Battle of Franklin on November 30, his army lost twelve generals killed and wounded; at the Battle of Nashville on December 15–16, the Army of Tennessee was virtually destroyed as a fighting force. Hood retreated to Mississippi with fewer than half of the forty thousand troops with whom he had started the invasion. On January 13, 1865, he resigned his command. In his memoirs, Davis claimed that he had not approved of Hood’s campaign. But contemporary evidence contradicts this effort to deny responsibility.2

Hood had left behind only Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry and Georgia militia to impede Sherman’s progress from Atlanta 285 miles to Savannah. From Richmond Davis sent a flurry of telegrams to Beauregard, to Howell Cobb (commander of the militia), and to William Hardee (commander at Savannah) trying to coordinate these efforts. He ordered the mining of roads with “subterranean torpedoes” and the destruction of bridges, livestock, and food crops in Sherman’s path. These actions did little to slow Sherman and much to anger him. Denouncing the use of mines as “barbarism,” Sherman forced prisoners to precede his soldiers to pry them up and defuse them. A Georgia citizen informed Davis that Wheeler’s horsemen had obeyed Davis’s instructions too literally. They burned “all the corn & fodder, [drove] off all the stock of farmers for ten miles on each side of the Rail Road,” and took most of the horses and mules. These exploits created such a backlash among the people that they “will not care one cent which army are victorious.” Davis, however, believed that his orders had not been carried out thoroughly enough. If they had been, he maintained after Sherman reached the sea and captured Savannah on December 21, “the faithful execution of those orders would have defeated his project.”3

The failure of Hood’s campaign and the fall of Savannah brought down a new torrent of censure on Davis’s head. The replacement of Johnston with Hood was the cause of the disaster, claimed the Richmond Examiner. In fact, declared the editor, “every misfortune of the country is palpably and confessedly due to the interference of Mr. Davis.” Several members of Congress echoed Senator Louis Wigfall’s denunciation of Davis as “an amalgam of malice and mediocrity.”4 One of Davis’s supporters lamented that the president “is in a sea of trouble. . . . It is the old story of the sick lion who even the jackass can kick without fear.” Ordnance Chief Josiah Gorgas, although a friend and confidant of Davis’s, deplored the plight of the Confederacy under his leadership. “Where is this to end?” Gorgas wondered. “No money in the Treasury, no food to feed General Lee’s Army, no troops to oppose Gen. Sherman. . . . Is the cause really hopeless? Is it to be abandoned and lost in this way? . . . When I see the President trifle away precious hours [in] idle discussion & discursive comment, I feel as tho’ he were not equal to his great task. And yet where could we get a better or a wiser man?”5

Many believed that a wiser and better man was available: General Robert E. Lee. Pressure mounted on Davis to appoint Lee as general-in-chief with virtually dictatorial powers that would, in effect, usurp the president’s authority as commander in chief. Davis likewise faced demands for the restoration of Johnston to command of the remnants of the Army of Tennessee. Mixed with these pressures were a welter of rumors and speculations about a wholesale reshuffling of the cabinet, the resignation of Davis, even a coup d’état to remove him from office. “There are rumors of revolution, and even of the displacement of the President by Congress, and investiture of Gen. Lee,” recorded one diarist breathlessly. “Revolution, the deposition of Mr. Davis, is openly talked of!” reported another.6

In the midst of this ferment came news of the fall of Fort Fisher on January 15, which closed Wilmington, North Carolina, as the last port for blockade runners bringing supplies for Lee’s army. As the noose tightened around the Confederacy’s neck, on January 16 the Senate overwhelmingly passed a resolution calling for the appointment of Lee as general-in-chief. The Virginia legislature sent Davis a similar resolution the following day. The president adroitly replied that he too had great confidence in Lee and was quite willing to give him command of all Confederate armies if Lee thought it compatible with his duties as field commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. The same day Davis offered Lee the position, knowing that he would decline, thus taking some of the sting out of the passage by the House that day of a bill creating the position of general- in-chief. A War Department official declared that the bill “is very distasteful to the President.” But “it is a question whether he will have the hardihood to veto it.”7 Davis signed it, however, and named Lee to the post on February 1. This time the general reluctantly accepted, with the apparent understanding that he would exercise his powers minimally, without infringing on the president’s prerogatives as commander in chief.8

• • •

THIS DENOUEMENT TEMPORARILY LANCED THE BOIL OF dissension in Richmond. At the same time, the issue of negotiations to bring the war to an end was coming to a head. Ever since Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in November, the North’s purpose to fight on to victory or exhaustion was clear. And it was also clear that the side closest to exhaustion was the Confederacy. Inflation and shortages had destroyed its economy; its armies were reeling in defeat; desertions had become epidemic; malnutrition and depressed morale prevailed among soldiers and civilians alike. A longing for peace spread over the South. A supporter of Davis told him in January that “making all proper allowances for habitual croakers, & personal dissatisfactions, I must express the deliberate conviction that there exists now an amount of conflict & despondency, which threatens to disintegrate & destroy our Government. Day by day things are growing worse.”9 The Georgia and Alabama legislatures passed resolutions calling for negotiations. Several congressmen introduced similar resolutions. Vice President Alexander Stephens once again pressed Davis to pursue any possible avenue toward peace.10

Davis had no faith in such a pursuit. He knew that Lincoln would insist on reunion and emancipation as the sine qua nons of peace. Davis continued to insist that the Confederacy could achieve independence by outlasting the North’s willingness to continue fighting. But he could not ignore the pressure for negotiations. He must at least appear willing to explore any opportunity for peace.

Such an opportunity opened up in the form of a letter from Francis Preston Blair at the beginning of 1865. A prominent Jacksonian Democrat during the 1830s and 1840s, Blair had been a political ally and friend of Davis’s. They had parted company when Blair helped found the Republican Party and became a sort of elder statesman in the Lincoln administration. He persuaded Lincoln to allow him to go to Richmond under a flag of truce as a “wholly unaccredited” agent to seek an interview with his old friend in the Confederate White House. The ostensible purpose was to obtain the return of papers looted by Confederate soldiers from Blair’s home in Silver Spring, Maryland, when Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederate troops raided to the outskirts of Washington the previous July. The real purpose, conveyed in a private letter to Davis, was to see if they could find common ground to end the war.11

Davis and Blair met for several hours in Richmond on January 12. Blair presented his personal plan for peace: a cease-fire between Union and Confederate forces followed by an alliance to drive the French out of Mexico, where Louis Napoleon had installed Austrian archduke Ferdinand Maximilian as emperor. Davis was skeptical about this audacious scheme, but he did not rule it out. The two men agreed to disagree, however, on the nature of such an alliance: Blair saw it as a step toward the return of the South to the Union; Davis perceived it as an agreement between two nations. Davis gave Blair a letter for Lincoln in which he agreed to appoint commissioners to a meeting with Union commissioners “with a view to secure peace to the two countries.”12

Blair went back to Washington with this message. Lincoln had no interest in Blair’s Mexican adventure. But he too wanted to keep alive the chance for peace. He authorized Blair to return to Richmond with a letter offering to receive any agents Davis “may informally send to me, with the view of securing peace to the people of our one common country.”13 After meetings with his cabinet and with Vice President Stephens, Davis decided to send a commission despite the difference between “the two countries” and “our one common country.”

Stephens had been one of the president’s most persistent critics, and to get him off his back Davis named him one of the three commissioners. The others were Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell, a former U.S. Supreme Court justice, and Senator Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia. All three had urged negotiations; Davis was sure that the process would founder on the one country/two countries impasse, so he wanted his commissioners to be personal witnesses to Lincoln’s “intransigence” as a way to convince the Southern people that independence could be achieved only by military victory.14

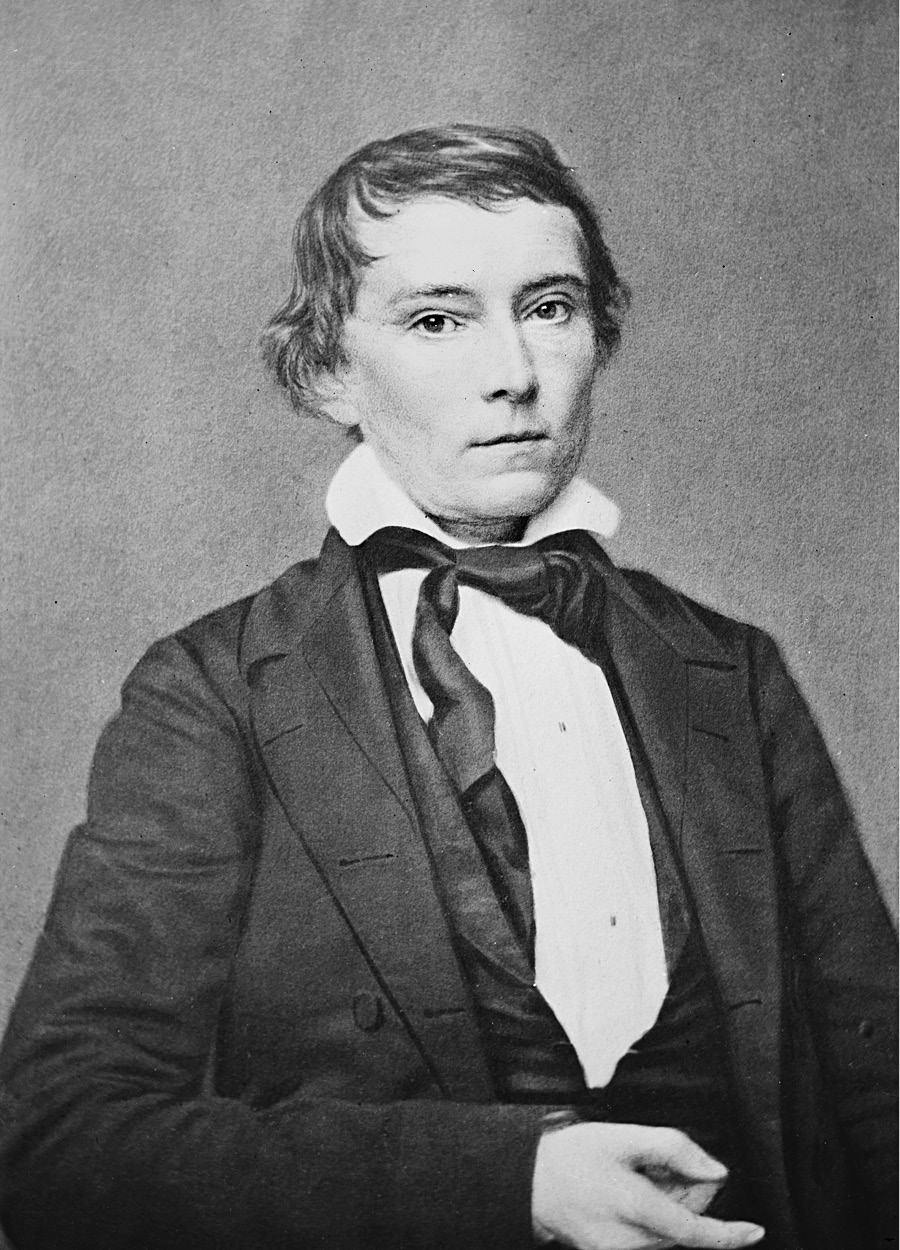

Alexander H. Stephens

Davis asked Secretary of State Judah Benjamin to draft instructions to the commissioners. Benjamin fudged the difference between one country and two countries by referring to Davis’s offer to negotiate and instructing them to seek a conference with Union agents “upon the subject to which it relates.” That would never do, said Davis. He restored “the two countries” language in the instructions. Benjamin shook his head and predicted that “the whole thing will break down on that very point.”15

If it had not been for the intervention of General Ulysses S. Grant, it would indeed have broken down. Lincoln had ordered Union officers not to allow the commissioners to cross the lines unless they agreed to his “one common country” letter as the basis for a meeting. Davis’s “two countries” instructions seemed to preclude a conference. By this time, however, the press in both North and South was full of speculation about the prospect of peace. The failure of the commissioners at least to meet would produce a huge letdown. Grant talked informally with Stephens and Hunter and telegraphed the War Department that he believed “their intentions are good and their desire sincere to restore peace and union. . . . I am sorry however that Mr. Lincoln cannot have an interview with [them]. . . . I fear now their going back without any expression from anyone in authority will have a bad influence.”16

This telegram caused Lincoln to come personally to Fort Monroe, where he joined Secretary of State William H. Seward for a meeting with the three Confederate commissioners on February 3. The four-hour meeting on a boat at Hampton Roads produced just what Davis expected—and probably wanted. Lincoln insisted on three conditions for peace: “1 The restoration of the National authority throughout all the States. 2 No receding by the Executive of the United States, on the Slavery question. . . . 3 No cessation of hostilities short of an end of the war, and the disbanding of all forces hostile to the government.”17 Three days earlier the United States Congress had passed—and Lincoln had signed—the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery, so condition number 2 would mean the end of the South’s peculiar institution.

The commissioners had no authority to accept any of these conditions, so they went home empty-handed. Their report to Davis contained only a bare-bones summary of the discussion. Davis, in order to fire up Southern resentment and determination to resist, wanted them to add some words about Lincoln’s insistence on humiliating terms. They refused, so on February 6 Davis provided such language in his message sending the report to Congress, which he also released to the press. Lincoln offered only the terms of a “conqueror,” he declared, demanding “unconditional submission to their rule.”18

That evening and three nights later Davis rose from a sickbed to give defiant speeches at mass meetings called to rally Southern morale. The Confederacy must fight on and prevail, he declared. It could never submit to the “disgrace of surrender” to “His Majesty Abraham the First.” Instead, Lincoln and Seward would find that “they had been speaking to their masters,” for Southern armies would yet “compel the Yankees, in less than twelve months, to petition us for peace on our own terms.”19 Even Davis’s critics praised these speeches. The editor of the Richmond Examiner admitted that he had never been “so much moved by the power of words.” Alexander Stephens thought Davis’s performance was “brilliant,” though he regarded the president’s forecast of military victory as “the emanation of a demented brain.”20

These meetings succeeded in reviving enthusiasm for the war, at least in Richmond. “Never before has the war spirit burned so fiercely and steadily,” exclaimed the Richmond Dispatch, while Josiah Gorgas echoed: “The war spirit has blazed out afresh.” The War Department clerk John B. Jones recorded that “every one thinks that the Confederacy will at once gather up its military strength and strike such blows as will astonish the world.”21

Several changes in the management of the war reinforced this optimism. Lee became general-in-chief at this time. James Seddon, worn out and in ill health, resigned as secretary of war and was replaced by John C. Breckinridge, who infused new energy into the War Department. One of Breckinridge’s first actions was to persuade Davis to accept the resignation of the much-maligned Lucius Northrop as commissary general and to appoint the able Isaac St. John in his place. The meager flow of rations to Lee’s army soon improved.22

But the euphoria in Richmond wore off as Sherman headed north from Savannah with the obvious purpose of cutting a destructive swath through the Carolinas and coming up on Lee’s rear in Virginia while Grant held him in a viselike grip in front. Charleston fell on February 18, when Sherman cut its communications with the interior. These developments increased the already intense pressure on Davis to restore Johnston to command of the forces concentrating in North Carolina to try to stop Sherman. Howell Cobb implored the president to “respond to the urgent—overwhelming public feeling in favor of the restoration of Genl Johnston. . . . Better that you put him in command—admitting him to be as deficient in the qualities of a General—as you or anyone else may suppose—than to resist a public sentiment—which is weakening your strength—and destroying your powers of usefulness.” Another Davis supporter acknowledged that the president had been justified in removing Johnston, but now it was necessary to reappoint him. “It would be equal to [the addition of] more than ten thousand effective men to the army. I entreat you, Mr. President, refuse no longer.”23

War Department clerk John Jones succinctly expressed Davis’s dilemma in the face of this pressure: “What will the President do, after saying [Johnston] should never have another command?” What Davis did was to produce a long memorandum, dated February 18, detailing his perception of all of Johnston’s failures and deficiencies. He intended to send it to Congress in response to resolutions by both houses calling for Johnston’s reappointment.24 But he did not send it. Instead, four days later he swallowed the bitter pill and named Johnston to the command. It was Lee who persuaded him to do so, by suggesting the fig leaf that Johnston be ordered “to report to me.” This was Lee’s one real exercise of authority as general-in-chief. “I know of no one who has so much the confidence of the troops & people as Genl Johnston,” Lee told Davis, “and I shall do all in my power to strengthen him.”25

• • •

IT WAS BEYOND LEE’S POWER TO STRENGTHEN JOHNSTON with significant reinforcements. Johnston could scrape together scarcely 20,000 effective men to confront Sherman’s 60,000, while in Virginia Lee had fewer than 60,000 to challenge Grant’s 125,000. Both Confederate armies were suffering an epidemic of desertions and absences without leave. Davis deplored this leakage, which was draining the Confederacy’s lifeblood. But many generals blamed the president himself for failing to uphold the summary executions of deserters that would discourage others from taking off. Like Lincoln, Davis pardoned or commuted the death sentences of many deserters. He hoped that clemency and an appeal to patriotism would work better than savage discipline in making men willing to fight. But this strategy did not seem to be working. And it led to one of Davis’s rare conflicts with Lee, who complained of the laxity that encouraged desertion. “I think a rigid execution of the law is mercy in the end,” wrote Lee. “The great want in our army is firm discipline.” Davis penned a biting commentary on Lee’s complaint. If the commander in chief saw fit to exercise clemency, he wrote, “that is not a proper subject for the criticism of a military commander.”26

The fact remained, however, that the Confederacy faced an acute manpower crisis in early 1865. Its armies had only 126,000 men present for duty of a total of 359,000 on its rolls. (At the same time, Union armies had 621,000 present of a total of 959,000 on the rolls.)27 In this dire state of affairs, many were prepared to consider what had previously been unthinkable—the freeing and enlisting of slaves as soldiers in the Confederate army.

Of course, slaves had always been an essential part of Confederate armies as laborers, teamsters, hospital attendants, laundresses, servants, cooks, and so on. In a message to Congress on November 27, 1863, Davis had recommended legislation to increase their number in order to release for combat many white soldiers serving in those capacities. Congress had complied; it had also repealed the draftee’s privilege of hiring a substitute and ended many occupational exemptions.28

These measures, however, failed to live up to their potential for increasing the number of combat soldiers. As early as July 1863, Davis began hearing from constituents suggesting the use of slaves as soldiers.29 A few Southern newspapers urged consideration of this radical idea. “We are forced by the necessity of our condition . . . to take a step which is revolting to every sentiment of pride, and to every principle that governed our institutions before the war,” declared an editor in Montgomery, Alabama, in the fall of 1863. An editor in Mobile, Alabama, concurred: “It is better for us to use the negroes for our defense than that the Yankees should use them against us. . . . We can make them fight better than the Yankees are able to do. Masters and overseers can marshal them for battle by the same authority and habit of obedience with which they are marshalled to labor.”30

Such ideas were anathema to most Confederates at that time, including Davis. When the proposal came from a significant source within the army itself, the president suppressed it. In January 1864 the best division commander in the Army of Tennessee, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, presented a paper to his fellow officers at the army’s winter camp in Dalton, Georgia. The North was winning the war, wrote Cleburne, because of its greater resources and manpower, including the freed slaves it was recruiting into the Union army. “Slavery, from being one of our chief sources of strength at the commencement of the war, has now become, in a military point of view, one of our chief sources of weakness.” Thus the Confederacy was threatened with “the loss of all we now hold most sacred—slaves and all other personal property, lands, homesteads, liberty, justice, safety, pride, manhood.” To avoid this disaster, said Cleburne, the Confederacy should enlist its own slave soldiers and “guarantee freedom within a reasonable time to every slave in the South who shall remain true to the Confederacy.”31

Thirteen brigadier generals and other officers in Cleburne’s division signed this paper. But officers in other units condemned the “monstrous proposition” as “revolting to Southern sentiment, Southern pride, and Southern honor.”32 One division commander was so upset that he went out of channels and sent a copy to Davis with a request that he crack down on “the further agitation of such sentiments and propositions,” which “would ruin the efficiency of our Army and involve our cause in ruin and disgrace.” The governor-in-exile of Tennessee urged Davis to “smother” the proposal so that it did not “gain publicity.”33 Davis agreed, and ordered Johnston to destroy all copies. “If it be kept out of the public journals,” he wrote, “its ill effects will be much lessened.” So successful was the “smothering” that Cleburne’s paper remained unknown outside a small circle until 1890, when one copy saved by a member of Cleburne’s staff turned up during the publication of the official records of the war.34

The issue of slave soldiers remained muted during most of 1864. But the manpower crisis in the collapsing Confederacy revived it by November. Davis approached the matter gingerly in a message to Congress on November 7. He recommended the appropriation of funds (where the money would come from he did not say) for the purchase of forty thousand slaves to be employed in noncombat roles by the army and freed after “service faithfully rendered.” He did not think it “wise or advantageous” to arm them as soldiers, he said before inserting a bombshell sentence: “But should the alternative ever be presented of subjugation or of the employment of the slave as a soldier, there seems no reason to doubt what should then be our decision.”35

No one missed the import of these words. “Can one credit it?” wrote a North Carolina woman who opposed the emancipation feature as well as the implied endorsement of black soldiers. “That a Southern man, one who knows the evils of free negro-ism, can be found willing to inflict such a curse on his country? . . . I consider such conduct undignified & unworthy of Mr. Davis, for that he really advocates the measure I cannot and will not believe.”36 The usual suspects among Davis’s most bitter critics, the Richmond Examiner and the Charleston Mercury, weighed in against the president’s proposal. “It adopts the whole theory of the abolitionist,” declared the Examiner. “The existence of a negro soldier is totally inconsistent with our political aim and with our social as well as political system. . . . If a negro is fit to be a soldier he is not fit to be a slave. . . . It would be a confession, not only of weakness, but of absolute inability to secure the object for which we undertook the war.” The Mercury branded Davis’s proposition as “inconsistent, unsound, and suicidal. . . . It would give the lie to our professions and surrender the strength and power of our position.”37

Congress did not act on Davis’s recommendation to buy and free 40,000 slaves “after service faithfully rendered.” But as the Confederacy’s prospects grew worse over the winter of 1864–65, the idea of arming the slaves would not die. A planter in North Carolina who owned 125 slaves offered 50 of them to Davis for the army. “I will pledge my word and judgment they will fight as well as the neg[ro] in the northern army. . . . We are on the verge of ruin unless this last resort is brought to bear.” A Georgia planter who had lost two sons in the war believed the time had come to enlist black soldiers. “We should away with pride of opinion—away with false pride,” he wrote to Davis. “The enemy fights us with the negro—and they will do very well to fight the yankees. . . . We are reduced to the last resort.”38

By February 1865 Davis was willing to commit openly to the last resort. In a letter to the editor of the influential Mobile Advertiser and Register, which supported this policy, the president expressed approval of “employing for the defence of our Country all the able-bodied men we have without distinction of color. . . . We are reduced to choosing whether the negroes shall fight for or against us.”39

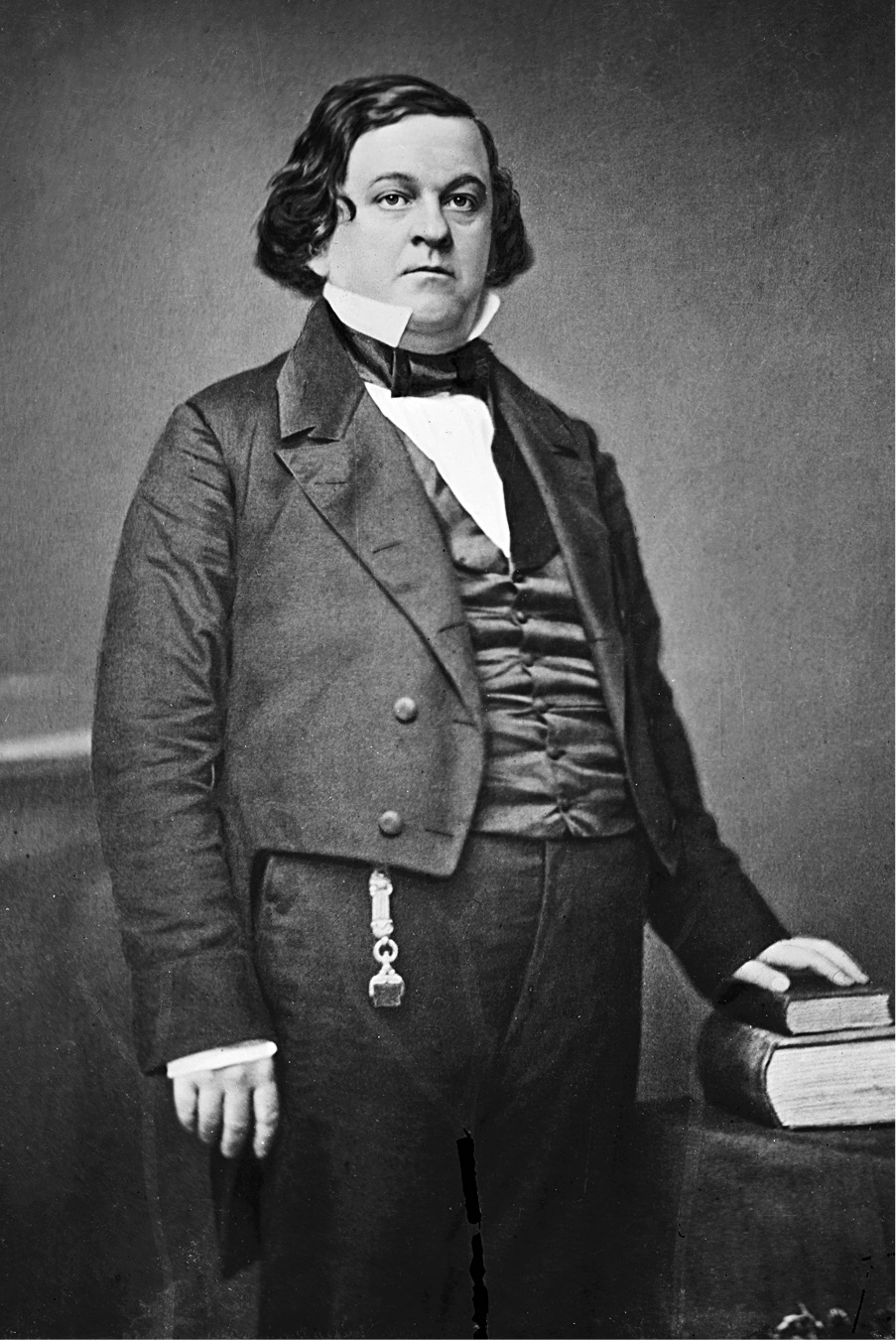

Howell Cobb

As the balance of opinion seemed to shift toward this position, the opposition became more shrill. “No question has arisen during the war that has given me so much concern,” Senator David Yulee of Florida told Davis. “This is a White Man’s government. To associate the colors in camp is to unsettle castes; and when thereby the distinction of color and caste is so far obliterated that the relation of fellow soldier is accepted, the mixture of races, and toleration of equality, is commenced.” Howell Cobb let the president know his opinion that “the proposition to make soldiers of our slaves [is] the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. . . . If slaves will make good soldiers—our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”40 Some white Southerners apparently preferred to lose the war than to win it with the help of black men. “Victory itself would be robbed of its glory if shared with slaves,” declared a Mississippi congressman. President Davis’s chief nemesis, Senator Louis Wigfall, said that he “wanted to live in no country in which the man who blacked his boots and curried his horse was his equal.”41

A bill introduced in Congress on February 10 for black enlistments therefore faced rough sledding in spite of Davis’s support—perhaps in part because of that support. Sponsored by Representative Ethelbert Barksdale of Mississippi (whose brother had been killed at Gettysburg), it authorized the president to requisition a quota of black soldiers from each state, with consent of their owners, but said nothing about freeing them. The House passed this measure by a vote of 40–37, but the Senate defeated it by one vote, 11–10, with both Virginia senators voting no. Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee came out publicly for the bill. Lee had earlier told a Virginia state senator in private that he favored the use of slaves as soldiers. On February 18 he made public his belief that such a policy was “not only expedient but necessary. . . . The negroes, under proper circumstances, will make efficient soldiers. I think we could do at least as well with them as the enemy, and he attaches great importance to their assistance. . . . Those who are employed should be freed. It would be neither just nor wise . . . to require them to serve as slaves.”42

Lee’s intervention proved decisive. The Virginia legislature instructed the state’s senators to change their votes to yes. They did so reluctantly, enabling the bill to pass by a vote of 9–8 (with nine abstentions and absences). Davis quickly signed it into law on March 13. The measure did not confer freedom on those who enlisted. But Davis ordered the War Department to issue regulations that ensured them “the rights of a freedman.”43 The president tried to jump-start the recruitment of black regiments. But the effort was too little and too late. Two companies began organizing in Richmond, but before this process got very far, the city fell on April 2 and the war was soon over.44

While the glare of publicity focused on the controversy over black soldiers, Davis and Secretary of State Judah Benjamin inaugurated a secret diplomatic mission to offer gradual abolition of slavery in return for British and French recognition of the Confederacy. The initiative for this mission came from Duncan F. Kenner, a wealthy sugar planter from Louisiana and a prominent member of the Confederate Congress. Kenner had been convinced since the fall of New Orleans in 1862 that slavery was a millstone around the Confederacy’s neck. He had urged Davis to consider an emancipationist diplomacy, but he made no headway until December 1864, when the president asked him to undertake such a mission. Davis of course could not commit Congress to an abolition policy, nor could Congress commit the states. But perhaps the Europeans would overlook these technicalities. Judah Benjamin convinced Davis that he could invoke his war powers to proclaim emancipation as a military necessity for national survival. When Lincoln had justified his Emancipation Proclamation on similar grounds in January 1863, Davis had denounced it as “the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man.” But that was then, and this was now.45

Kenner’s difficulties in getting to Europe foretokened the failure of his mission. Because of the fall of Fort Fisher, he could not take a blockade runner from Wilmington. He traveled incognito to New York and boarded a ship to France, where Louis Napoleon gave him a cold shoulder. His experience in Britain was no better. On March 14 Lord Palmerston informed Kenner and the Confederate envoy James Mason, who had accompanied him to London, that the British government could not recognize a nation that had not firmly established its existence. “As affairs now stood,” Mason reported to Benjamin, “our seaports given up, the comparatively unobstructed march of Sherman, etc., rather increased than diminished previous objections.”46

• • •

BY MARCH 1865 THE CONFEDERACY WAS FALLING APART. The railroads had broken down and could scarcely move the little freight that the inflation-ravaged economy produced. Deserters roamed the countryside and robbed civilians of what little sustenance they had preserved. Government officials, including President Davis, sent their families away from Richmond because of the prospect of its imminent fall. A clerical worker in the War Department wrote in her diary on March 10: “Fearful orders have been given in the offices to keep the papers packed, except such as we are working on. The packed boxes remain in the front room. . . . As we walk in every morning, all eyes are turned to the boxes to see if any have been removed, and we breathe more freely when we find them still there.”47

J. C. Breckinridge

When John C. Breckinridge became secretary of war in February, he ordered a survey of Confederate resources available to carry on the war. The results were shocking: no money; no credit; shortages of food, clothing, forage, munitions, animals, and men; no more foreign imports because of the fall of Wilmington. Breckinridge and Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell were convinced that the war was lost and that the government should negotiate a peace even with reunion while it still had leverage to salvage something from the ruin. They approached Lee, who agreed that matters were almost hopeless. But Lee—and for that matter Breckinridge—refused to defy the president so long as Davis was determined to fight on. Lee emerged from a meeting with Davis impressed by his “remarkable faith” in the cause and his “unconquerable will power.” The general told a Virginia congressman that as long as the war continued he would fight “to the last extremity.”48

In Davis’s mind, that last extremity had not arrived. “There are no vital points on the preservation of which the continued existence of the Confederacy depends,” he had told Congress in November 1864. “Not the fall of Richmond, nor Wilmington, nor Charleston, nor Savannah, nor Mobile, nor of all combined, can save the enemy from the constant and exhaustive drain of blood and treasure which must continue until he shall discover that no peace is attainable unless based on the recognition of our indefeasible rights.”49

By the beginning of March 1865 three of those cities had fallen and the other two would soon follow. A Senate committee asked Davis what he intended to do. According to the committee’s report, the president told them that he meant “to continue the war as long as we were able to maintain it. . . . The existence of the Confederate Government was a fact, and that he was placed in office to defend and preserve it, that he had power to negotiate for the continued existence of the Government, but none whatever for its destruction.”50

Davis liked to cite the example of Frederick the Great, who faced a powerful coalition that greatly outnumbered him in the Seven Years’ War but attacked and defeated his enemies in detail and saved Silesia for Prussia. He had this example in mind when he wrote to Braxton Bragg on April 1 that “our condition is that in which great Generals have shown their value to a struggling state. Boldness of conception and rapidity of execution has often rendered the smaller force victorious. To fight the Enemy in detail it is necessary to outmarch him and to surprise him.”51

It was not to be. While attending Sunday service at St. Paul’s Church the next day, Davis was handed an urgent message from Lee. The enemy had broken the lines at Petersburg, and the capital must be evacuated. That night Davis and his cabinet boarded the last train from Richmond as the city, its warehouses set afire by departing Confederate troops, began to burn behind them. Davis’s destination was Danville, Virginia, the new Confederate capital. From there on April 4 he issued a proclamation to the Southern people urging them to continue the struggle. “Relieved from the necessity of guarding cities and particular points,” he declared, the army would be “free to move from point to point, and strike in detail the detachments and garrisons of the enemy, operating in the interior of our own country, where supplies are accessible. . . . Nothing is now needed to render our triumph certain, but the exhibition of our own unquenchable resolve. Let us but will it, and we are free.”52

Petersburg, Virginia: Dead Confederate soldiers in the trenches of Fort Mahone

Because of the breakdown in communications, few people read this appeal and fewer heeded it. After a week in Danville the cabinet learned of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. They hastily fled south to Greensboro, North Carolina. Joseph Johnston’s small army was still in the field, near Raleigh, and Davis hoped to use it as a nucleus to build up a larger force to continue the war. “We must redouble our efforts to meet present disaster,” he told North Carolina’s governor, Zebulon Vance. “An army holding its position with determination to fight on and manifest ability to maintain the struggle will attract all the scattered soldiers and daily and rapidly gather strength.”53

Richmond, Virginia: Ruins on Carey Street

Davis had gone from a state of unreality to one of fantasy. “Poor President,” commented a Confederate soldier. “He is unwilling to see what all around him see. He cannot bring himself to believe that after four years of glorious struggle we are to be crushed into submission.”54 Johnston’s army surrendered to Sherman on April 26. Davis continued south, two steps ahead of Union cavalry scouring the countryside looking for him. One by one his cabinet members resigned, but he hoped to make his way across the Mississippi River to join Edmund Kirby Smith’s troops, who had not yet surrendered. On May 10, however, Union cavalry caught up with his small party, including his family, near Irwinville, Georgia.

The long ordeal of civil war was over. For Davis there began a new ordeal of imprisonment for two years awaiting a trial for treason that never came. Twenty-four years of a long life remained during which he never recanted the cause for which he had fought and lost.