CHAPTER 5: CHINA AND THE WORLD

'Therefore one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the most skillful. Seizing the enemy without fighting is the most skillful.'

Sun Tzu, The Art of War [6th century BCE]

In November 2006, Beijing underwent a sudden transformation. Factories were closed down to ensure the air was clear. Half a million cars were banned from the city centre to ensure traffic flowed smoothly. Giant hoardings were put up to hide the worst eyesores, and were painted with vast pictures of animals – zebras, giraffes, elephants. Flowerbeds were rolled out. Trees were planted. Huge slogans were painted saying, 'Friendship, peace, co-operation and development.' In some ways, it seemed like a dress rehearsal for the 2008 Olympics, yet this was far more than a rehearsal. Although it received scant attention in the western media, this was a huge even tin China. Beijing was playing host to the heads of 48 African governments.

For all the well-publicised statements of intent of the western governments to free Africa from poverty, none of them had ever given African leaders this much attention and put them so clearly in the spotlight for people at home to see. It is no wonder that the Chinese are winning many African hearts and minds. While the western world is busy talking, and treating them like poor children who need nurturing, it seems to some Africans, the Chinese are actually doing something, and treating them, at least superficially, like adults. At the Beijing summit, President Hu promised to double aid to Africa by 2009 and provide US$5 billion in loans and credits, to train fifteen thousand African professionals and set up a fund for building schools and hospitals. More importantly, the Beijing summit focused on two thousand trade deals with Africa, to boost China–Africa trade. With US$42 billion-worth of trade in 2006, China has already replaced the USA as Africa's leading trading partner.

On the surface at least, China's courting of Africa has a clear intent. China needs resources to sustain its economic growth and Africa has them. Their main target has been oil from the Sudan, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Nigeria, but they also want platinum from Zimbabwe, copper from Zambia, tropical timber from Congo-Brazzaville and iron ore from South Africa. And it's not just Africa that China has been courting. Through the whole of his presidency, George W Bush has not spent more than about a week in neighbouring South America. Yet in 2004, President Hu Jintao spent over two weeks there, assiduously talking with South American governments and pledging billions of dollars of investment in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, Bolivia and Cuba. This pattern has continued and the Chinese leaders, once thought of as being somewhat isolationist, have gone on a charm offensive around the world. In 2006, for instance, Premier Wen Jiabao went to fifteen different countries, while President Hu visited Russia, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Nigeria, Kenya, India and Pakistan, not to mention Vietnam where he met most Asian leaders, the Beijing African summit and a major visit to the USA.

Almost unnoticed, too, by the western world, which has had its attention focused firmly on the Middle East, China has been extending its trading links with its neighbours in such a way that it is set to replace the USA as the dominant force in South-east Asia. While American trade with the region has stayed pretty static for most of the twenty-first century so far, China's has been racing away. And it's not simply money that is being exchanged. In northern Thailand, Chinese engineers have blasted away the rapids on the Mekong River so that large boats can gain access to Chinese factories there. Chinese construction companies are building motorways to link Kunming in China to Hanoi in Vietnam, Mandalay in Burma and Bangkok in Thailand.

Of course, it is resources that are the driving force behind these overtures, which is why Australia, too, is being drawn into China's expanding friendship circle. But in 2006, Hu made a friendly visit to India, a country it went to war with in 1962, and pledged to double trade and to bid jointly for oil developments on which both nations had previously been competing. Then in spring 2007, Premier Wen paid a remarkably cordial visit to China's bête noire, Japan, and the real possibility of some kind of detente between these two old enemies seemed possible (see Chapter 8, China and Japan).

Peaceful rise?

All of this seems to fit with China's intention of keeping its prosperity growing to lift its people out of poverty without making any ripples in the world – an intention famously described by Zheng Bijian, chair of the China Reform Forum as a 'peaceful rise'. After Tiananmen (see pages 63–66), Deng Xiaoping advised that China should 'observe developments soberly, maintain our position, meet challenges calmly, hide our capacities and bide our time, remain free of ambition, never claim leadership.' Deng felt that China should never throw its weight around, threaten its neighbours nor disturb world peace. All the signs are that this is the policy that China has pursued in relation to the world over the last decade. When the Americans accidentally bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in the former Yugoslavia in 1999, the Chinese allowed a brief upsurge of public protest, but quickly damped it down. They did the same in 2001, when an American spy plane collided with a Chinese fighter over Chinese territory, killing the pilot.

Politically, China's attitude seems to be to keep itself to itself – and it expects other countries to do likewise. That is why it brooks no interference on the issue of Tibet, which it regards as a purely internal matter. The same goes for Taiwan (see Chapter 6). For the same reason, China was quietly disturbed by the NATO intervention in Yugoslavia in 1999. It was also dead against foreign intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan.

African strings

It is this non-interventionist stance that has allowed China to enter into trading links with African countries, for instance, without looking too closely at their internal politics. The problem with this is that it is beginning to bring it into, perhaps unanticipated, conflict. While the West often extends aid or loans in Africa only to regimes it is happy with, or providing certain conditions are met, China appears to offer money with no questions asked and no strings attached – which is very appealing to some African leaders, but causes anxiety in the West, especially among human rights organisations. In 2004, when the International Monetary Fund held up a loan to Angola because of suspected corruption, the Chinese stumped up US$2 billion instead. Similarly, while the West has been trying to isolate President Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, the Chinese have stepped in with US$2 billion dollars worth of loans, not to mention Chinese arms. And when the African Union expelled François Bozizé of the Central African Republic after a violent coup, China gave him a huge loan and invited him to China.

It is the Sudan, however, that has been the biggest bone of contention. Sudan has become a focus of international concern because of the ethnic slaughter in the Darfur region, where 200,000 people have died and 2.5 million have been forced out of their homes. Yet apparently heedless of the Darfur situation and the moves in the rest of the world to impose sanctions, China helped build a pipeline to develop Sudan's oil resources and now takes two-thirds of the country's oil. Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir's fabulous new palace is being built courtesy of an interest-free loan from China. What upset critics most, though, was that China used its position on the UN Security Council to dilute resolutions pressuring the Sudan government to allow a UN force in to protect the people of Darfur. When questioned about China's attitude in 2006, Foreign Minister Zhou Wenzhong said, 'Business is business. We try to separate politics from business, and in any case the internal position of Sudan is an internal affair, and we are not in a position to influence them' (quoted in Will Hutton's The Writing on the Wall (2007)).

China yields

The chorus of international pressure on China over Darfur has grown more intense, and there are signs that the Chinese are responding. In April 2007, the Chinese sent a special envoy to persuade Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir to accept the UN peacekeeping force, and by June the pressure had worked. This is not enough for some, however, since it is Chinese weapons that are being used against victims in Darfur. Pressure from US politicians, Hollywood stars such as Mia Farrow and human-rights groups has pushed China to go further, but China argues that its softly, softly approach is working – and that it is more than willing to cooperate. At a news conference in May 2007, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu insisted, 'I can say that on the Darfur issue, China and the United States have the same goal. We hope to solve the issue by political means, so we are ready to make joint efforts with the international community, including the US.' Yet the negative publicity over Darfur continued in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics, as film director Steven Spielberg resigned as the Games' artistic director.

As China is beginning to learn, it cannot engage economically with the rest of the world without engaging politically. In Africa, moreover, they are coming up against criticism not just for the unsavoury governments they are willing to deal with, but also their own behaviour. On the one side is the trading pattern in which, some say, China takes Africa's resources, then floods it with cheap products and even food that make it impossible for Africans to compete. In December 2006, South African president Thabo Mbeki warned Africa that it must not allow China to become like one of the old colonial powers. On the other, Chinese rigs and mining operations in Africa are acquiring a reputation for poor safety, exploitative wages and job insecurity.

International alignment

So far, under Hu and Wen, China has been playing its hand remarkably well, and allaying many of the fears people had about the country in the Mao era. Indeed, an international poll in 2005 of opinions of the public around the world by the US- based Pew Research Center found that China is far more popular and trusted around the world than the USA is. Despite the criticism over its dealings with unsavoury regimes, and its trading practices, China has successfully kept a low profile, and has generally done the 'right thing' when necessary. In the 1950s, China went to war against the USA to protect North Korea and lost millions of soldiers, but when North Korea conducted its nuclear test in autumn 2006, China not only joined the USA in condemning Kim Jong-il, but supported the UN resolution imposing sanctions on North Korea.

On the other hand, China's interests in maintaining stability in the region are clear with North Korea. That isn't the case with Iran. China has refused to back the tough sanctions against Iran that Europe and America want to use to halt Iran's nuclear programme. It may be that the Chinese believe the Iranians should be left to develop nuclear power in peace, as it is, but there is no doubt that China wants Iranian oil and gas, and has signed a US$16 billion contract for it.

As China's economy expands, and it extends its global reach, it will find itself not only exposed to more and more pressures like those it has faced over Darfur and Zimbabwe. It will also find that its impact on the world may bring animosity in places it doesn't always expect.

Trade wars?

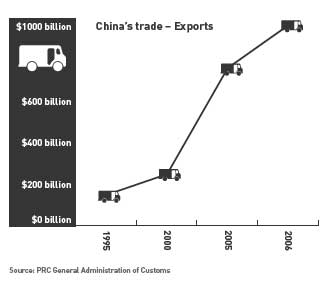

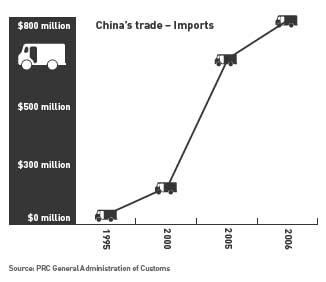

One area of potential conflict is trade and finance. The USA already has a massive trade imbalance with China – in fact, the biggest in history. In 2005, the USA imported US$240 billion of goods from China and exported back just US$40 billion. Over the next few years, that trading deficit is likely to increase. The only reason it is sustainable is that China is happy to put its entire surplus into dollars.

American manufacturers, and many American workers, are unhappy with this surplus, as are politicians who worry about this dependence. They complain that they are being unfairly undercut by Chinese factories and that the American market is being continually swamped by the dumping of cheap Chinese products. Six American industries – textiles, clothes, wooden furniture, colour TVs, semiconductors and shrimping – have already won special tariff protections against China. The pressure for more is building up, with Democrats making a noise about both the loss of American jobs and China's record on human rights. More and more Congressmen are drafting anti-China legislation, from putting up trade barriers to getting China suspended from the World Trade Organization.

If any of the more severe measures actually gets through, it is likely to have dramatic impact. At the very least, China will turn its economic power on Europe instead, where the China effect has so far been small – though there has already been opposition in Europe to any increase in Chinese imports – with potentially devastating effects on jobs and businesses in Europe. At worst, it could provoke the Chinese to give up on the dollar for their vast foreign reserves, provoking an economic meltdown worse than the 1930s, as America's finances collapse.

| China's Top Export Destinations 2006 ($ billion) | |||

| Rank | Country | Volume | % Change* |

| 01 | United States | 203.5 | 24.9 |

| 02 | Hong Kong | 155.4 | 24.8 |

| 03 | Japan | 91.6 | 9.1 |

| 04 | South Korea | 44.5 | 26.8 |

| 05 | Germany | 40.3 | 23.9 |

| 06 | The Netherlands | 30.9 | 19.3 |

| 07 | United Kingdom | 24.2 | 27.3 |

| 08 | Singapore | 23.2 | 39.4 |

| 09 | Taiwan | 20.7 | 25.3 |

| 10 | Italy | 16.0 | 36.7 |

*Per cent change over 2005

Source: PRC General Administration of Customs, China's Customs Statistics

| China's Top Import Suppliers 2006 ($ billion) | |||

| Rank | Country | Volume | % Change* |

| 01 | Japan | 115.7 | 15.2 |

| 02 | South Korea | 89.8 | 16.9 |

| 03 | Taiwan | 87.1 | 16.6 |

| 04 | United States | 59.2 | 21.8 |

| 05 | Germany | 37.9 | 23.3 |

| 06 | Malaysia | 23.6 | 17.3 |

| 07 | Australia | 19.3 | 19.3 |

| 08 | Thailand | 18.0 | 28.4 |

| 09 | Russia | 17.7 | 37.3 |

| 10 | Singapore | 17.7 | 7.0 |

*Per cent change over 2005

Source: PRC General Administration of Customs, China's Customs Statistics

INFO: BRITAIN'S CHINA BOOM

Britain has not suffered much from the China effect, yet. Indeed, if anything, China's boom has given Britain quite a comfortable ride in the last decade. Some jobs have been lost to cheap Chinese competition, such as those at Rover cars, but often these were in industries that were close to the edge anyway. On the other hand, wages at the bottom of the scale have been kept low, and so too has the price of manufactured goods. This means that inflation and interest rates have stayed low, fuelling soaring property prices. With interest rates low and property prices rising, British consumers have felt comfortable borrowing against the equity in their homes or simply on credit to spend at an unprecedented level. All this spending has created more jobs in retail, services and a whole raft of industries that rely on personal consumption.

Oil wars

Many people believe that oil production is now at a peak – as high as it will ever be. Although new oilfields are still being found and developed, they cannot compensate for the fall-off in production from existing fields as they begin to run out. Not everyone agrees, but oil consumption around the world is still climbing, and in China it is rising faster than anywhere else. In 2003, China shot past Japan to become the world's second largest oil consumer after the USA, and since then it has accounted for 40 per cent of the total growth in global demand for oil. If current trends continue, China will overtake the USA in 209 years – even though the USA's consumption is still rising. So just where is all this oil going to come from?

On the whole, China has been remarkably careful to avoid competing with the western world too strongly. That's why it's willing to take Iranian oil, and has played a key part in developing fields away from the Middle East in Africa, especially Sudan and Angola, and South America. These may not prove sufficient, and if the USA gets into hostilities with Iran, China may be forced to take sides, or lose a vital source of oil.

Military build-up

Over the last decade, according to London's International Institute for Strategic Studies, China's military spending has tripled, and seems to be accelerating. In 2006 alone, Chinese spending on arms grew by 15 per cent. For a country that insists that it is rising peacefully, this seems an odd contradiction, and people have begun to wonder just what this arms build-up is for. Some believe it is aimed at Taiwan, and begin to ask the question, what would America do if China attacked Taiwan? Could this be the start of a superpower war? Most believe this is unlikely since it is in both China's and the USA's interests to maintain the status quo in Taiwan (see Chapter 6).

It could just be, though, that China is building up its forces to the point where the USA will decide the cost of intervention to save Taiwan is simply too high. That's what some American hawks say. The aim of the spending has turned the mass numbers of the PLA (People's Liberation Army) into a smaller, nimbler but technologically advanced force that can operate at the same level as American forces. Its navy also has cruise and other anti-ship missiles designed to pierce the electronic defences of US ships. All the same, Chinese military spending is just a tenth of American spending, and even less than British spending, so it seems unlikely to be able to sustain a serious war against the USA, even if it wanted to. So a war over Taiwan seems unlikely.

If the Chinese weapons are not for Taiwan, what else could they be for? It may be simply defensive security. Twice in the twentieth century, China was invaded – the last time with devastating effects. It also has land frontiers 22,000 kilometres (13,670 miles) long and a coast 18,000 kilometres (11,185 miles) long, which need protecting. It may also be that China is anticipating a conflict over resources. It has already sent its navy out in a war of wills with Japan over disputed oilfields.

Democratic future?

At the moment, China seems to be content to play a low- key role in the world. A poll conducted in China in 2006 showed that 87 per cent of Chinese people thought their country should take a greater role in world affairs and should soon match that of the USA. The Chinese were probably thinking of pride in their country, and their growing belief that they should occupy their 'rightful place' in the world rather than seeking to dominate the world in any imperialistic sense. The problem is that their rightful place could be at other people's expense. Moreover, China remains a one-party state, which often suppresses dissidence, and so far it has not been choosy about the states with which it fraternises. Over the last twenty years the number of democracies in the world has doubled so that two-thirds of the world's nations are now democracies. It is just possible that China's rise may see this swing towards democracy slow or even decline – unless, of course, China itself moves towards democracy.