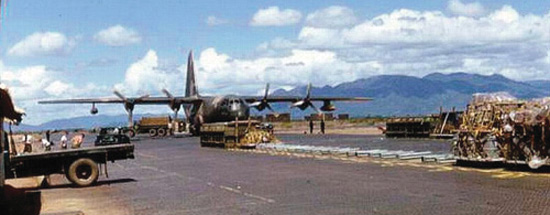

US soldiers at Đà Nẵng Air Base in 1965.

I believe the term ‘hauling trash’ predated the Viêtnam War. The first time I ever heard anyone use it was in the spring of 1965 when I was on temporary duty at Ubon, Thailand on the flare mission. Willy Donovan, one of the other loadmasters, had come to Okinawa from C-135s in MATS. Willie was a big Beatles fan. One day he sang a little ditty to the tune of Yellow Submarine that went ‘We all live in a green garbage can’ etc and etc. It was about that time that I first heard the term ‘trash hauler’. I have an idea the term may have originated in MATS. I started out in TAC at Pope and never heard it there. However, we rarely carried cargo except when we were TDY overseas or were on training exercises with the Army. In Viêtnam, that was pretty much all we did. We had scheduled passenger missions every day but most of our missions carried general cargo mostly ammunition and fuel, usually in barrels although some airplanes were loaded with bladders and pumps to haul it in bulk. Some missions were into forward airfields in the field and some were from the major supply bases to other facilities around the country. During my second overseas tour in 69-70, the common term for C-130s and C-123s was ‘mortar magnet.’

Sam McGowan, loadmaster/flare kicker in the 35th TCS, 6315th Operations Group at Naha Air Base on Okinawa. He is the author of Anything Anywhere Anytime and Trash Haulers and The Cave; an exciting novel about a C-130 flareship crewmember who is shot down over Laos and declares his own personal war on the anti-aircraft gunners who shot him down.

US soldiers at Đà Nẵng Air Base in 1965.

Việtnam was formerly part of French Indo-China, together with Laos and Cambodia which lie along its western border and is bounded in the North by China. After the defeat of the French forces in July 1954 it was split into two countries, the Republic of South Việtnam and the Communist North, using the 17th Parallel as the dividing line. The victors were the Communist Việt Minh (‘League for the Independence of Việtnam)1 forces led by General Võ Nguyên Giáp and they planned to take control of the South using a new Communist guerrilla force called the Việt Công (VC) or the National Liberation Front (NLF). The VC campaign increased in intensity in 1957 until finally, in 1960, Premier Ngô Đình Diệm appealed to the United States for help. Special ‘advisers’ were sent in and in 1961 President Lyndon B. Johnson began the negotiations which led to total American involvement. In February 1965 the Việt Công stepped up its guerrilla war and the first American casualties in Việtnam occurred when the VC attacked US installations in the South. The US retaliated with strikes by US naval aircraft from carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin against VC installations at Đồng Hới and Vit Thu Lu. The guerrilla war escalated until in 1965, the South Việtnamese administration was on the point of collapse. The US responded with a continued build-up of military might, beginning with Operation ‘Rolling Thunder’, as the air offensive against North Việtnam was called.

The first C-130 tactical transports were introduced in the Southeast Asia theatre in 1961 during the crisis in Laos. As at the outbreak of the Korean War fourteen years earlier, America was largely ill-prepared for ‘conventional’ warfare on the Asian mainland. PACAF was a nucleardeterrent force, like the majority of US commands at this time, a third of its 600 aircraft being made up of F-100D/F tactical fighters. Only fifty-three C-54 and C-130A aircraft comprised its transport fleet, the majority of units being stationed in Japan, the Philippines and Taiwan. In Japan C-130As of the 815th TCS, 315th Air Division were based at Tachikawa Air Base or ‘Tachi’ as it quickly became known, northwest of Tokyo and those of the 35th and 817th TCS, 384th TCW, at Naha Air Base, Okinawa; a few aircraft of the 315th Air Division were also detached at Naha. In the Philippines, three squadrons operated in the 463td TCW at Clark Air Base and two others operated from Mactan Air Base. In Formosa (Taiwan) three C-130 squadrons in the 374th TCW operated from Kung Kuan Air Base.2

Before total US intervention in Việtnam, the PACAF Hercules had been used mainly for logistic support between the home bases and bases in Thailand and South Việtnam. After the spring of 1965 however, the Hercules became the prime transport aircraft in the Pacific theatre. Its first task was to airlift troops and equipment to South Việtnam from Okinawa: thus from 8-12 March 1965 C-130s deployed a Marine battalion landing team to Đà Nẵng; and on 4-7 May, they carried the Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade to South Việtnam in 140 lifts. Casualties were numerous and the Hercules carried out many air evacuations.

A line up of USAF C-130As sits on the Lockheed-Georgia Company production flight line in Marietta, Georgia, in 1957 prior to delivery. One of the first Hercules built, complete with the original Roman nose, sits at the far left. The Hercules in the middle (55-0005) would eventually be left behind at Tân Sơn Nhứt AB, South Việtnam, as that country fell to Communist forces in 1975. The aircraft to its left (55-0007) was transferred to the Bolivian Air Force in 1988. The C-130A in the foreground (55-0009) was destroyed in a rocket attack at Đà Nẵng AB, South Việtnam in 1967. (Lockheed)

Paratroops of the 1st Brigade, 101st US Airborne Division during the airlift from Kontum to Phan Rang, South Viêtnam. During the spring and summer of 1966 the Brigade was transported on five occasions by the C-130s. Each deployment involved 200 Hercules lifts and each operation was mainly re-supplied by air. C-130B (58-0752) in the 463rd TCW, in the background, survived the war in SE Asia and was modified to WC-130B; later it reverted to C-130B and finally was sold to the Chilean Air Force in 1992. (USAF)

From early 1965 C-130s from the PACAF and MATS wings were regularly rotated into South Việtnam. More than any other aircraft, the Hercules was destined to become the workhorse of the Việtnam War, just as the Dakota had proved itself to be in World War II. Beginning in the spring of 1965, Fairchild C-123 Providers and de Havilland Canada C-7 Caribous were stationed permanently in-country, but the transport-dedicated versions of the Hercules were rotated in and out of strips nearest the combat zones in South Việtnam from bases in the Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) region. Based mainly at the major airfields of Đà Nẵng, Tuy Hòa, Cam Ranh Bay and Tân Sơn Nhứt, the C-130 tactical transports were deployed to South Việtnam on a temporary duty basis.

It soon became obvious that transports and their crews would be needed in large numbers to support US intervention in southeast Asia. The primary function of the Hercules was aerial transportation but they would have to perform many other roles besides; for infra-theatre aeromedical evacuation, as ‘airborne battlefield command and control centres’ (ABCCCs), AC-130 gunships, rescue aircraft, flare-dropping aircraft and even ‘bombers’. In South-East Asia the Hercules was to see widespread service, not only with the USAF, but with the US Navy, the USMC (as the KC-130F), the Coast Guard and the VNAF (Việtnamese Air Force), in what was to become a long and bloody conflict against a very determined and implacable enemy. Beginning in 1972 Project ‘Enhance Plus’ gave the VNAF over 900 badly needed helicopters, fighters, gunships and transports, including thirtytwo hastily withdrawn C-130As from ANG units in the US. In addition, the RAAF operated C-130Es on airlift duties between Australia and South Việtnam. These were from 36 Squadron and from 1966, 37 Squadron. From 1965 to 1975 40 Squadron RNZAF operated five C-130Hs on logistic flights between New Zealand and Saïgon and Vũng Tàu, South Việtnam.

The only Hercules aircraft based permanently in Southeast Asia were the special mission aircraft such as flare ships, SAR aircraft, special operations aircraft and later, gunships. Starting in January 1965, C-130As and crews drawn from the squadrons at Naha, Okinawa, were attached to the 6315th Operations Group (TAC) control for use as flare ships in South-East Asia. Operating from Đà Nẵng, the flare-dropping C-130As and their crews were used mostly for the interdiction of the Việt Công infiltration routes through Laos. The C-130As were designed to operate in conjunction with the ‘fast movers’ (fighter-bombers) such as the F-4 Phantom, in night strikes against VC convoys using the Hồ Chi Minh Trail. Two code-names accompanied the start of the flare-dropping project. Operations which were carried out over the ‘Barrel Roll’ interdiction area in northern Laos were termed ‘Lamplighter’, while those flown against targets in the ‘Steel Tiger’ and ‘Tiger Hound’ areas of southern Laos were known as ‘Blind Bat’. (Eventually the two operational areas in Laos were merged into one and ‘Blind Bat’ was normally used to describe flare-dropping missions generally).

‘No, bats are not blind’ wrote Sam McGowan ‘but we might as well have been on those dark nights over the Hồ Chi Minh Trail in Laos and southern North Việtnam. It’s too bad we didn’t have the senses of a bat because if we had, we might have been able to see something on the truck routes that wound their way through the dense forest beneath the wings of our C-130A. Operation ‘Blind Bat’ was perhaps one of the most interesting if not dangerous missions of the Việtnam War in the years between 1964 and 1970, when the mission was terminated. Because the Communist infiltrators took advantage of the darkness of night to make their way south out of North Việtnam, the US Air Force worked diligently to find a way to detect the nearly illusive trucks and other means of transportation by which the North sent supplies to their troops in South Việtnam. Dropping flares from transports was nothing new in Việtnam; the technique had been used in World War II and Korea. In South Việtnam C-47s and C-123s flew nightly flare missions in support of ground installations that might find themselves under attack. But the C-130 ‘Blind Bat’ mission was different; our targets were trucks, not enemy squads and we were flying interdiction missions, not support for ground forces.

Destroyed C-130A 55-0042 21st TCS flareship in its revetment following the mortar and sapper attack on Đà Nẵng at midnight on 30 June/1 July 1965 was evidently aimed at the ramp where there were three C-130A flareships. 55-0042 was destroyed and burnt, except for the tail section. 55-0039 was also destroyed and 55-6475 was eventually repaired and returned Stateside. Air Police Staff Sergeant Terry Jensen (35th APS) was killed in action.

A dramatic LAPES drop, somewhere in Việtnam. This tactic was a low level self-contained system capable of delivering heavy loads into an area where landing was not feasible from an optimum aircraft wheel altitude of five to ten feet above the ground. Their load, which could consist of two pallets with a total weight of up to 38,000lbs were resting on roller bearing tracks in the floor of the aircraft. Small parachutes were deployed at the proper time to jerk the cargo from the aircraft to land on the runway and theoretically come to rest in a short distance. These deliveries ceased after one eight-ton load of lumber skidded into a mess hall off the end of the runway crushing three Marines to death. Another LAPES delivery of artillery rounds ploughed through a bunker, killing two Marines.

‘The C-130 flare mission had its beginnings sometime in 1964 when a detachment of C-130As was sent to Đà Nẵng Air Base, perhaps by way of Tân Sơn Nhứt, where the 6315th Operations Groups was maintaining a ‘Southeast Asia Trainer’ mission at the time. According to the late Bill Cooke, who was one of the two navigators involved, the crews went in to brief for the night’s mission and when they got back to their airplanes they discovered that they had been spray-painted black! Just when the first mission was flown is disputed. While it is known that missions were flown in November 1964 with Cat Z maintenance troops from the 21st TCS flying as kickers, the mission probably actually started many months earlier using only loadmasters who threw the flares out the paratroop doors. There is no doubt that in April 1965 the mission became semi-permanent at least and two or three C-130As were kept at Đà Nẵng until the project was cancelled and a new one was simultaneously established at Ubon AB, Thailand.

From Đà Nẵng, the C-130As of the 6315th Operations Group at Naha, Okinawa flew nightly missions out over Laos seeking out targets. The C-130s operated as part of a four-ship formation made up of the flareship, a pair of USAF B-57 Canberra attack bombers and a USMC EF-10 EWO aircraft known as ‘Willy the Whale’. With the C-130 serving as a mother ship to lead the formation to the target, the team would leave Đà Nẵng and hit west and later north, to seek out the enemy and destroy him.

‘Though automatic flare launchers were later developed (but never used by ‘Blind Bat’) the mission in the early days was very much a Rube Goldberg arrangement. The ‘flare launcher’ was actually an aluminium tray that had been manufactured in the Sheet Metal Shop back at Naha, while the flares were stored in wooden bins tied to an airdrop pallet. The crews were equipped with the ‘finest’ detection equipment - which consisted of the pilots’ and navigator’s eyeballs and a pair of binoculars!’

At peak strength, the ‘Blind Bat’ project numbered six C-130As and twelve crews, mainly derived from the 41st Troop Carrier Squadron. The first ‘Blind Bat’ loss occurred on 24 April 1965 (incidentally the first Hercules loss in Việtnam) when C-130A 57-0475 and its 817th Troop Carrier Squadron/6315th Operations Group crew at Korat RTAF Base hit a mountain during a go-around in bad weather. The aircraft had lost two engines and was low on fuel and was carrying a heavy load. Major Theodore R. Loeschner and his five crew were killed.

C-130B 61-0950 of TAC unloading a tank in Vietnam. This Hercules was finally retired from the Air Force in 1994 and was sold to Romania in 1996.

Coming in to land at Khâm Đức.

‘Even though the equipment was rudimentary at best, the mission evidently was a thorn in the Communist side, for on 1 July 1965 a mortar and sapper attack on Đà Nẵng was evidently aimed at the ramp where the three C-130 flareships were parked, waiting to go out on a mission. Two airplanes were destroyed in the attack and the third was damaged, along with an airlifter C-130B that had the misfortune to be parked nearby. The flareships were the first C-130s ever lost to enemy action.3

‘The flareship mission was seen as limited successful by the Air Force, but research was begun to develop a new weapons system with both reconnaissance and attack capability that eventually led to the AC-130 gunship and the B-57G. Most of the techniques and much of the equipment used on the gunships had been developed and/or tested by ‘Blind Bat’ crews. Though there was still a mission for ‘Blind Bat’, cost considerations led the Air Force to terminate the programme in 1970 after the gunships came on the scene. Funding for the mission transferred to a new programme using modified B -57s that had been equipped with sophisticated detection equipment.

‘In early 1966 the flare mission moved from Đà Nẵng to Ubon, Thailand and the flare mission changed somewhat. Instead of departing as part of a formation, the C-130 flareships began going out single-ship to patrol a specified area looking for targets. Each flareship was allotted a certain number of strike flights each evening and had the option of calling for more through the ‘Moonbeam’ Airborne Combat Command Centre which circled high over Laos each evening controlling airstrikes. And we received a new name as the ‘Blind Bat’ call sign came into use. Actually, ‘Blind Bat’ was one of two call signs used by the flareships with ‘Lamplighter’ being the other. ‘Blind Bat’ missions operated over Laos while the Lamplighters went north, across the Anamite Range into North Việtnam. According to some veterans of the mission flareships at one time operated as far north as the Hànôi-Hảiphòng area, but increasing enemy defences forced the C-130s to operate further south in the ‘Route Package One’ and ‘Two’ areas south of Vinh. By 1967 the threat of SAM’s in North Việtnam caused a cessation of operations over the North.

‘In the spring of 1966 shortly after I reported in to the 35th Troop Carrier Squadron at Naha, I had my introduction to the flareship mission. I was already a seasoned veteran after flying numerous airlift missions in Tactical Air Command C-130Es while on TDY from my previous base at Pope, next to Fort Bragg in North Carolina. I had even been on an airplane that took a few hits as we were landing at Đông Hà the previous November, when there was nothing there but a shack for passengers waiting to board Air Việtnam. I had flown one other mission over the north since I had reported in to my new assignment at Naha. That one had been a BS bomber missions dropping leaflets as part of Project ‘Fact Sheet’, the special mission my squadron bore sole responsibility for. Tonight would be different. While on previous missions we had sought to elude the enemy, tonight, on my orientation flight as an observer before our crew started missions the following evening, we were looking for him and there was almost a 100% chance we were going to find him; the chances were he was going to let us know he was there. I went in-country as the senior loadmaster of a 21st Troop Carrier Squadron crew commanded by Captain Bob Bartunek, with Captain Steve Taylor as co-pilot, Lieutenant Dick Herman as navigator, Staff Sergeant Cecil Hebdon as engineer and Airmen Mike Cavanaugh, Willy Donovan, Sam McCracken and myself as loadmaster/flare kickers. ‘To say that our tour at Ubon was exciting is an understatement. Every other night our crew took off sometime between just before dark and midnight and headed northeast; out over Laos and sometimes up into North Việtnam. No, we were not shot at every time we flew, at least not that we could see, but we were certainly shot at enough! My introduction to North Việtnamese anti-aircraft came about within the first five minutes after we penetrated the skies of North Việtnam. Excitement gripped the pit of my stomach as I heard the pilot say, ‘Go ahead and depressurize, so the loads can put out the chute.

‘I signalled to the rest of the crew to go ahead and open the aft cargo door slightly to extend the aluminium flare chute. As soon as the chute had been placed into the narrow opening between the raised C-130 ramp and the partially open door, one of the other loadmasters used the hand pump to pressurize the system and force the door down on the chute to hold it in place. I could feel the pressure in my ears as the flight engineer opened the outflow valve and allowed pressure to escape to bring the inside of the airplane up to the 10,000 feet of elevation at which we were flying. Even though there were mountains below us that reached to within a couple of thousand of feet of where we were, it was an elevation that was high enough to keep us clear of all the small arms and .50-calibre fire that the Army helicopter crews flying in South Việtnam thought was ‘heavy’ fire. There were big guns where we were going, dozens of 37 and 57mm anti-aircraft guns, all of which could reach us at 10,000 feet and even a few 85s, the same guns that had made the skies over Germany so deadly for my father and uncle as they flew missions in their B-24s.4

‘When it was secure, one of the other guys climbed onto the door to take his place as the flare kicker while another stood by with a flare in his hand ready to put it in the chute when the pilot called for it.

‘Since I was crew loadmaster with my own crew, I was on the interphone cord which is where I would be the next evening when we went up on our own. Tonight each of the eight members of my crew was on a mission in one of the four airplanes that were flying.

C-130B-LM 61-0969 of the 29th TAS/463rd Tactical Airlift Wing at Cam Ranh Bay in July 1969. This aircraft, which was delivered to TAC in January 1962, was sold to Argentina in February 1994.

KC-130F/R BuNo149789 of VMGR-152 which served with MAG-36 and MAW-1 at Biên Hỏa Air Force Base (Ken Roy).

‘When the pilot’s words came through my headset ‘load four flares’ I held up four fingers. The other loadmasters put four flares in the chute and then set the fuses for an eight-second delay.

‘We were approaching the Mu Gia Pass where we would drop a string to see if there were any targets in what was the most heavily defended place in southern North Việtnam.

‘Drop four!’

‘As the words came through my headset the guy on the door, who was also wearing a headset let fly with the four flares he was holding in place with his feet. A few seconds later the sky behind us lit up as the four flares burst into brilliance. And just as they did, I saw brilliant white winking lights on the ground somewhere below us. I was looking out the left paratroop door at the ground. Out of the lights came cherry-red balls like those fired by Roman candles. They rose slowly at first and then quickly accelerated toward us. ‘I want my mother!’ Those are the thoughts that went through my mind as I realized for the first time in my life that someone down there was trying to kill me.

On 28 February 1968 C-130E 64-0522 of the 779th TAS, 314th TCW was hit in the port wing by intense small arms fire on take-off from Sông Bé Army Air Field ALCE and MACV Compound in South Việtnam. Major Leland R. Filmore and his co-pilot, 1st Lieutenant Caroters, turned away and flew over a village south of the airfield but received more gunfire. The port wing tanks burst into flame that quickly engulfed the aircraft but the pilots were able to land the burning aircraft back on the runway where the courageous fire crew unsuccessfully fought to extinguish the flames though all five crew and five passengers escaped with only minor injuries before the Hercules and its cargo was completely destroyed. Major Filmore was awarded a Silver Star for his part in this event.

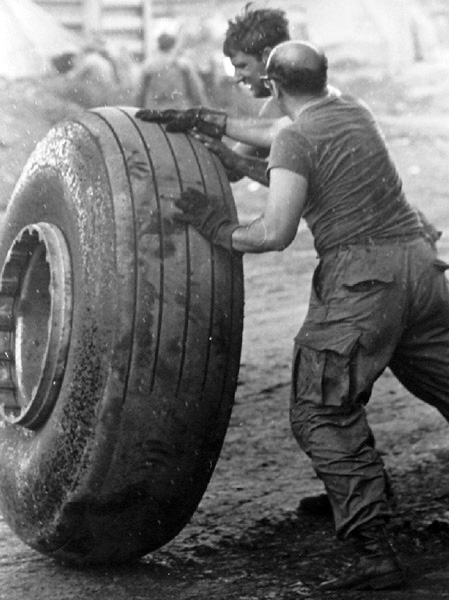

January 1967, South Việtnam. TAC C-130E 62-01841 of the 50th TCS at a forward airstrip having unloaded men of the 1st Infantry Division (the United States Army’s oldest continuously serving in the Regular Army and officially nicknamed ‘The Big Red One’). On 20 April 1974 C-130E 62-01841 departed Guam-Agana NAS on a training mission to perform touch-and-go’s. Prior to one of the landings, the no. 3 or no. 4 engine had been shut down. The aircraft experienced a blow-out of tyres on the right hand main landing gear on touchdown. It yawed right, skidded across a taxiway and parking ramp narrowly missing a parked line of A-3 fighters. It finally came to rest against an embankment where the remains of the aircraft completely burned out. All six men on board were killed.

‘Our flares had no more than popped when we were greeted by cherry-red tracers, 37mm fire, coming up somewhere far below. ‘I want my mother!’ That was my thought when I realized someone down there was trying to kill me! But the burst of 37mm rose to burst harmlessly in the sky about 100 feet or so above us. The pilot said they were off to our right by about the same distance, but I could have sworn they went right by my nose! It suddenly occurred to me that the next three months were going to be an exciting time.

‘Now that ‘Charlie’ had made his presence known, we knew what area to avoid by just the right distance to keep out of the way of his shells and we went on to a typical night of flare kicking over North Việtnam. A few minutes later a flight of fighters, F-4s from Đà Nẵng arrived on station and we sent them down after the trucks that were making their way through the narrow pass.

‘My tour started out during the dry season and we saw and attacked a lot of trucks, but then it went into the rainy season and truck traffic on the Trail became light. A lot of our missions were aimed at targets that had been identified from reconnaissance photographs taken earlier in the day. ‘Suspected’ truck parks and ammo dumps were usually the targets in such instances. Other times we would just patrol the skies looking for the lights of trucks on ground below. Since the NVA used shielded headlights, the trucks were difficult to spot. And as often as not when we did find a convoy, they would speed into the shelter of a ‘village’ where they were off-limits to air strikes. Yes, the US news media was lying when they told the country that ‘unrestricted’ air strikes were being conducted in Southeast Asia. The air strikes were very restricted, so much so that legitimate enemy targets were quite often spared.

‘One of our best nights came about strictly through a series of mistakes, all of which linked together to become a triumph. We had been told during our briefing to look for a ‘suspected’ ammunition dump along the banks of a river in North Việtnam. Our intrepid officers had spotted the ‘dump’ and had called in a flight of USAF F-4s to take it out. But just about the time the fighters arrived in our area and right after Bartunek had told us to load six flares into the chute, the pilots lost sight of the target completely. If they couldn’t see it, they couldn’t tell the fighters were it was. The fighter pilots only had a few minutes of loiter fuel and they were starting to complain. Willy Donovan was sitting on the cargo door holding the flares in place with his feet and his legs were beginning to ache. Bartunek was getting frustrated. Finally, Willy had had enough. He raised his feet and let the six flares slide out into the night, where they burst into a brilliance that turned the night beneath us into near-day. With the illumination, someone, I think it was Dick Herman, spotted the target again just as Bartunek was raking Willy over the coals for letting the flares go without being told to do so. Everyone settled down and got back to the business of trying to destroy the enemy.

‘The first F-4, a Gunfighter out of Đà Nẵng, roared in over the target and dropped his bombs. They hit close to the target, but not close enough to do any damage. His wingman came along behind him. He not only missed the target completely, his bombs fell on the opposite side of the river nearly a mile away! But through a fluke of good fortune his bombs fell smack in the middle of the real ammo dump which was cleverly concealed and had not been detected. Even though he missed his aiming point by a mile (literally!) the errant fighter pilot destroyed the real ammo dump. We heard later that the pilot was put in for a Silver Star for the mission.

‘Missing targets was a common occurrence on night missions by fighters in Southeast Asia. Every crewmember who flew the ‘Blind Bat’ or C-123 ‘Candlestick’ mission can attest to the phenomenal lack of accuracy on the part of the fighter pilots, especially the F-4s. Of all the airplanes working over the Trail at night, the WW II vintage A-26 Invader was undoubtedly the best. One afternoon we went up early and worked with an A-26 near the Plain of Jars. For nearly an hour the ‘Nimrod’ pilot worked over the target, first dropping bombs, then napalm, then firing rockets, after that his guns and finally dropping his own load of eight flares on the supply dump. It was undoubtedly the best airshow I have ever seen.

USMC KC-130 BuNo148248 of VMGR-152 leaving Subic Bay on the island of Luzon in the Philippines for Đà Nẵng in 1969. From 1967 to 1975 the bulk of VMGR-152’s missions were directly in support of action in South-East Asia. Detachments typically lasted five days and operated out of Đà Nẵng Air Base. In addition to aerial refueling and Marine Logistic (MarLog) cargo missions, VMGR 152 ‘GVs’ dropped flares in support of ground troop operations at night. At its peak the squadron was flying 900 missions a month and continued this high tempo of operations well into 1967.

‘Along with the A-26s, the USMC and Navy A-4s were the most accurate bombers working the Trail. Air Force F-4s were undoubtedly the worst. The F-100s and A-1Es were pretty good, but they were flying mostly in South Việtnam in support of ground forces and not working over the Trail. (Navy A-1s operating from carriers operated over both North Việtnam and Laos.) The AC-47 gunship was tried over the Trail just before I got to Ubon but this was one mission the venerable old Gooney Bird was not suited for. In less than a week Charlie shot down both of the ‘Spookies’ and AC-47s spent the rest of the war working in South Việtnam or in the lesser defended areas of Laos. It was not until the advent of the super gunship, the AC-130 that an effective truck killer came on the scene.

‘There was one area where the F-4s were good, though and that was with CBUs, or cluster bombs. The CBU had been developed for use against antiaircraft sites and the Communists were well aware that it they revealed their position, a flight of CBU-carrying F-4s would soon be on the way to take them out. Watching a CBU strike was something else. One night a particular gun made the mistake of firing on us when we were a little bit out of range. Bartunek called in a flight armed with CBUs. I watched as the F-4 drew red tracers from the enemy gun as he made his bombing run. Suddenly, tiny winking white lights erupted all over the place from which the red tracers were originating - and the red cherry balls suddenly ceased. I must admit it sort of did my heart good to witness the gun crew’s destruction.

‘Even though we were flying out of Thailand, we were not safe from enemy attack. One evening while my crew was out on a mission, an enemy team tried to probe the base - right outside the ‘Blind Bat’ enlisted men’s quarters! A Chinese Nùng guard managed to sound the alarm.5 He got off one shot with his shotgun as an NVA special ops soldier was cutting his throat. But the one shot was enough. A few shots were fired but the enemy soldier disappeared into the night.

‘One evening our crew had an unusual experience. We were called out of Laos to drop flares between Ubon and the Mekong River which constituted the border between Thailand and Laos. We were told to look for helicopters on the ground. It turned out that North Việtnamese aircraft had penetrated the area, evidently to deliver supplies to insurgents in the area or an enemy team. We did not see anything. Later we learned that an F-4 had been scrambled off of Ubon and had picked up the target on his radar, but in the rush to get him off the ground, the ordinance team had failed to pull the pins on his Sidewinders. The missiles failed to fire and the unidentified airplane - probably a helicopter - got away.

KC-130F of VMGR-152 landing at Đông Hà in 1967.

A 2nd Battalion, 503rd Regiment, 173rd Airborne Division paratrooper leaving a C-130 during Operation ‘Junction City’.

Dropping supplies during Operation ‘Junction City’.

‘Sometime in late 1966 a ‘Blind Bat’ crew from my squadron, the 35th TCS, tangled with a North Việtnamese MiG and managed to live to tell about. They were working in northern Laos when ‘Moonbeam’ diverted them to a point just inside the Laotian border about 120 miles west of Hànôi to provide flare support for friendlies on the ground who were under attack. The crew was busy dropping flares when they were alerted by ‘College Eye’, an EC-121 radar ship orbiting over Thailand that a pair of MiGs had just taken off from Giá Lam Airport and were headed their way. It takes a MiG about ten minutes to cover 120 miles and it was not long before the crew had company. No American fighters were anywhere close to their position and the ‘Blind Bat’ flareship was not armed. The crew had only one weapon at their disposal and that was the manoeuvrability of their airplane, combined with rugged terrain beneath them. They dived toward the ground, knowing they were over mountains and had no maps of the terrain on board the airplane. But they had radar and a sharp navigator. Using the radar to keep from hitting a ridge, the C-130 crew wove their way through the valleys while the MiGs searched for them with their own radar. The enemy fighters were so close that the energy from their search radar caused waves on the C-130 crew’s set. When they got back to Ubon later that evening, the fighter pilots in the officers club were disappointed that they had missed a chance at a MiG. The C-130 crew was just glad to be alive!

‘Another crew that was glad to be alive was also from the 35th TCS. Major Frank’s crew was working near the Communist stronghold of Tchepone in Laos when they took a hit from a large calibre anti-aircraft gun. This particular gun was a legend. The bad guys had it mounted on a railroad car and kept it hidden inside the mouth of either a tunnel or a large cave near the city. They would roll it inside where it was impervious to air strikes and then bring back out again to take a pot-shot at a ‘Yankee Air Pirate.’ The ‘Blind Bat’ crew thought their number was up. The round set fire to their left wing and was burning brightly fed by the hydraulic fluid in the primary system. Major Frank had rung the ‘prepare to bailout’ bell and was just about to sound the ‘bailout’ signal when the loadmasters called that the fire had gone out. After consuming all the hydraulic fluid in the system, the fire burned itself out before reaching the fuel tanks that were on either side of the dry bay in which it was burning. Still, they had problems. The airplane would still fly, but all hydraulic pressure to the ailerons had been lost. Staff Sergeant Kenney, the engineer, went in back to help the loadmasters, Airmen Benstead, Taylor, Harris and Delaney, to put the fire out. Frank and the co-pilot, Lieutenant Nelson, used all of their strength on the controls while Kenney and the loadmasters provided additional muscle pulling on tie-down straps that they had attached to the aileron bell crank. (Kenney now says they didn’t use a strap, but that was the story the crew told when they got back to Naha.) They managed to bring the airplane to a safe landing at Nakon Pha’m, Thailand where each of the crewmembers kissed the ground when they jumped out of the airplane.

‘Getting hit on a ‘Blind Bat’ mission was almost a regular occurrence, but surprisingly, casualties were fairly low. Two ‘Blind Bat’ flare ships were lost during the course of the war, along with their crews. Some crewmembers were wounded by flak on other missions. There was some bitter humour with the mission as well. McNorton, a loadmaster in the 21st TCS, was called ‘Combat McNorton’ because of his thirst for adventure. Before Seventh Air Force put a stop to it, C-130 crews frequently fired their M-16s at the ground during strikes and sometimes used flares as bombs. I set up one bombing mission myself. We dropped a load of six after setting the fuses for a long interval over the Mu Giá Pass. McNorton threw out a flare and hit a B-57 with it. As I remember, it was McNorton who came up with the ‘Blind Bat’ black beret and patch that flare ship crewmembers wore at Ubon.

C-130 56-0471 ‘Surprise Package’ ‘Blind Bat’.

C-130 performing a LAPES drop to the US Army 1st Cavalry Division ‘The Air Mobile Division’ at An Khê in Gia Lai Province in the Central Highlands region of Viêtnam in 1965

‘A navigator had an experience of rather mixed blessing sometime in 1969. By this time ‘Blind Bat’ had received some new equipment, including the ‘Black Crow’ ignition detector and other equipment, including a system that required a navigator/operator to sit in a seat mounted on the outside of one of the paratroop doors. This particular navigator was coming inside the airplane when he accidentally caught the rip cord of his parachute and extracted himself from the airplane! He made it to the ground safely where he spent an uneasy night until the helicopters came for him at dawn. He was picked up and returned to Ubon - where there was a message waiting for him that he had been passed over for promotion and was being RIF’ed out of the service!

‘Bob Bartunek reminded me of an incident that happened one night when we were - literally! upside down in a C-130! The navigator had drifted off and let us get a little bit too close to a flak trap. When the guns opened up, the pilots saw the tracers coming right at us. For years I thought Steve Taylor was flying, but Bartunek says that on this particular evening he was flying from the right seat and Taylor was in the left seat calling fighters. I know where I was - sitting on the door holding the flares in the chute with my feet. All of a sudden our A-model Herky bird was rolling all the way over onto its back! This is no shit, Sherlock! Bartunek rolled the airplane upside down and pulled through in a split-S - which probably kept us from getting shot out of the sky. And the whole thing was so smooth that not a single one of the flares came out the tray. The navigator, who was still half asleep when we went through the aerobatic manoeuvre, said there was no way we could have gone upside down - because his coffee had not even spilled!

USAF C-130 taxiing at Đông Hà.

‘There is an amazing footnote to the story of our crew’s time at Ubon on the ‘Blind Bat’ mission. Although I never connected the dots, our crew played a role in one of the most amazing events of the Việtnam War, although we had no idea that we were a part at the time. In February 1966 US Navy Lieutenant (jg) Dieter Dengler was shot down over Laos in an A-1 Skyraider. After evading the enemy for several hours, he was finally captured by Pathet Lao troops and because he was captured by them, he remained in Pathet Lao custody. Dengler was kept in a decrepit Laotian camp along with two other Americans, an Air Force lieutenant who had been shot down in a helicopter the year before and a kicker from an Air America C-46 that was shot down in 1963 and four Asian Air America employees who were on the same airplane. Although no one at Ubon had an inkling of the role we were playing, our nightly missions passed over the camp where the PoWs were being held and our presence was a key element in the escape plans they made. In late June a few weeks before our crew finished our tour, the seven men escaped. Dengler and Air Force Lieutenant Duane Martin went off together while the others went in different groups. The rainy season had begun and they were unable to signal the nightly C-130 as they had planned. Finally, after they had been in the jungle for about five days, Dengler and Martin managed to signal a C-130, but no rescue mission came to save them. Apparently, it was our crew.

‘After almost a week in the jungle, the two airmen were weak from fatigue and illness and were starving. Martin, who was already near death from malaria, convinced Dengler to go with him to try to steal some food from a nearby village. They were spotted by a young boy and a villager rushed out and attacked them with a machete. Martin was killed by the blow and Dengler, who was kneeling beside him, jumped up and rushed the village then fled into the forest and eventually returned to the abandoned guerrilla camp where they had been hiding. Demoralized and to the point he was ready to die, Dengler determined that he make a signal that the damned C-130 crew couldn’t miss! He revived the small fire he had built a few days before and put torches aside to be ready to set the flimsy huts on fire. Later that night the C-130 did come over and he burned the village to the ground! The crew did, in fact, spot his fires - it was us - and when we got back to Ubon the debriefing officers were very excited about the account. Yet, for some reason, no rescue mission was sent out. Apparently the higher-ups in intelligence decided it must not be an American.

‘When no rescue force appeared, Dengler was still demoralized and he wasn’t sure if he had actually seen the C-130 or was hallucinating. He woke in another tropical thunderstorm but decided to try go find one of the parachutes from one of the flares. Just before daylight he found it and reading his account of how much that piece of cloth meant to him brought tears to my eyes when I read his account. He took the parachute and put it in his knapsack and used it a few days later to signal Air Force A-1 pilot Lieutenant Colonel Eugene Dietrich when he was finally spotted and rescued. ‘None of us had an inkling that the fires we had seen that night had been set by an escaped PoW and it wasn’t until Bob Bartunek and Dieter Dengler got in contact through the Skyraider Association that the pieces were put together. (Bartunek commanded an Air Force A-1 squadron later in the war.) Although I knew about Dieter’s book, I had never read it until after the movie about his ordeal was released in the summer of 2007. Had I read it sooner I would have known that Dengler owed his life to the parachute from the flare we dropped over him that night.’

In the period from February 1958 until 1965 about a dozen C-130s were lost worldwide. Then from 1965 to 1972 sixty-five Hercules (including gunships) were lost in South-East Asia alone. Moreover the airlift crewmen killed or MIA numbered 269. In 1966 seven Hercules were lost in South Việtnam. In 1967 thirteen were lost. In 1968 operations intensified and the heaviest losses among Hercules in South Việtnam were recorded, with a total of sixteen C-130s being lost.

At first the US Army and the USAF held opposite views on how best to deploy troops to the combat zones. The Army considered that air mobile operations using helicopters to deploy troops was a more efficient method than the paratroop landing method initially favoured by the Air Force; moreover the USAF were convinced that fixed-wing air-landed operations would deploy more troops to a given area than a paradrop ever would. From then on, airlift aircraft were used to deposit troops, cargo, equipment and supplies, except of course on a larger scale than the Army’s air mobile helicopter force, which it complemented. In the assault role the Hercules was almost as versatile as the air mobile, since the one hundred rudimentary landing strips capable of accommodating C-l 30s rarely proved an obstacle to the aircraft’s excellent short field performance.

PACAF was not designed for counterinsurgency (COIN) operations and so at the outset, the first aircraft to deploy to Việtnam were mostly provided by Tactical Air Command on a rotational basis. After April 1965 four Tactical Air Command squadrons, deployed from the US on ninety-day tours of temporary duty (TDY) backed up PACAF’s own four C-130 squadrons; by the end of 1965 there were thirty-two Hercules operating incountry, positioned at four bases. All came under the unified control of the Common Service Airlift System (CSAS) and its Airlift Control Center (ALCC) which were subordinate to 834th Air Division, organized on 25 October 1966 at Tân Sơn Nhứt AB in the suburbs of Saïgon and responsible to the Seventh Air Force for tactical airlift within South Việtnam. ALCC functioned countrywide through local airlift control elements, liaison officers, field mission commanders and mobile combat control teams. ALCC also controlled the C-130s that were rotated into South Việtnam on one- and two-week cycles from the 315th Air Division in Japan.

C-130B 60-0301 turns at the end of the short runway at Bam Bleh, Việtnam on 23 November 1966. The transport was one of several taking troops of the First Cavalry Division back to their base camp at Ăn Khê after an operation. Air Force aircraft made daily flights to fields like this one carrying troops and supplies to front line units. This aircraft was delivered to TAC in May 1961 and ended its days in 3 Squadron, Royal Jordanian Air Force from December 1973 to June 1979.

Supplies being dropped to ground troops during Operation ‘Junction City’ in Tây Ninh Province in February 1967.

In 1965 two US Army paratroop brigades were held in Việtnam as a central reserve force quickly available for offensive or reaction operations. In August the 173rd Airborne Brigade was airlifted from Biên Hòa to Pleiku in central Việtnam in 150 Hercules flights. During ‘Operation New Life-65’, which began on 21 November the 173rd made a helicopter assault into an improvised airstrip forty miles east of Biên Hòa; seventy-one C-130s arrived over the next thirty-six hours to resupply them, the first landing within an hour of the initial assault. Meanwhile, for twenty-nine days beginning on 29 October the C-130s kept the 1st Cavalry Division supplied during operations against Piel Me, a small Special Forces camp about halfway between Buôn Ma Thuột (Ban Me Thout) and Pleiku.6 The Việt Công had laid siege to the camp and the US, South Việtnamese and Montagnard native allies fought them in daily firefights with air support by helicopters and fighter bombers. Using a rough airstrip at Catecka Tea Plantation near the battle area the C-130s delivered on average 180 tons of supplies and munitions per day.7

On 20 November Captain John Dunn’s crew in the 774th TAS, 463rd Tactical Airlift Wing made another in their series of flights, to Pleiku, Đà Nẵng and then Tân Sơn Nhứt. First Lieutenant (later Lieutenant Colonel) Bill Barry, a native of Scranton, Pennsylvania and a fully fledged Tactical Airlift navigator on his second tour8 recalled:

‘We were making our last airlift stop of the day. As we pulled into the cargo area at Đà Nẵng. ALCE (Airlift Control Element) told us we’d be going from there to Tan Son Nhut (Tân Sơn Nhứt) but there would be a longer than usual delay to reload because some higher priority missions were coming in just behind us.

‘Captain John Dunn was an ex-fighter pilot (F-100s), new to airlift and having to look after a crew rather than just himself for the first time; but he was a good pilot and a nice guy. Married, he was in his thirties and had a wife and two boys. Hal Thorson, an ex-farm boy and college wrestler, was the co-pilot. Like me, he was a totally new trainee. Quiet and good natured, Hal was married and had a son. Hal was my age, mid-twenties. John, Hal and I were commissioned officers. Then there were the enlisted men (also known comically as the ‘enlisted swine’). Ed Frame was our flight engineer. A sergeant with several years of experience as an aircraft mechanic, he was new to flying and being a crew member. His job was to monitor the cockpit instruments and watch for and correct, when possible, any mechanical problems, instrument errors, or engine fluxes which took place in flight. Finally, our loadmaster was a young airman, Carl Gross. He was about 20, big and lively and a novice like Hal, Ed and me. His job was to move the cargo, tie it down so it wouldn’t move in flight, or roll on takeoff or landing. He also monitored the rear of the airplane in the air and threw the switches and locks that held the palletized cargo in place during airdrops. Most crews were a mix of new guys and veterans. Ours was less experienced than most of the others. Dunn’s hands were going to be fuller than most. Though he was a good, experienced pilot, he had no experience in TAC airlift and that was a big factor. The other four of us on the crew were all inexperienced in numerous ways, as we were soon to find out. There were a lot of young aviators mixed in with veteran flyers to make up the 24 crews the squadron had. Usually, all 24 were never present at any one time, someone always being TDY. The crews, together with a small number of personnel from Wing, flew all our assigned missions in the twelve aircraft the squadron had. The crews also performed all the planning, alert and administrative functions of the squadron. Everyone had one or more other tasks in addition to flying the line.

‘Now we sat in the cockpit of our plane and watched another of our Wing’s C-130s pull into the Đà Nẵng cargo area next to us. We recognized the call sign and even the co-pilot’s voice as he asked the ALCE for offload instructions as the plane taxied in after landing. They parked off to our left and slightly behind us. From our cockpit windows we could see the unusual number of fire trucks and ambulances which were following them as they shut down their engines and prepared to offload. We weren’t paying too much attention until Carl Gross came over our rear interphone system and said, ‘Look at the crew scatter from that plane!’ As soon as their propellers had stopped spinning and they were clear to come out of the cockpit, the entire crew ran from the stopped aircraft as if they were evading a cockpit fire. They then stood away from the plane at a distance of thirty yards. Now our interest was up.

USAF C-130As and E’s of the 817th TAS/374th TAW (YU) and 776th TAS/314th TAW (DL) and a C-123 on the line in Việtnam.

South Việtnamese civilians assist with construction of an airbase in South Việtnam.

‘Since our on-load was going to be delayed, we had nothing better to do than walk over to see what the problem was with the other aircraft. We knew the entire crew, who were part of our temporary duty unit back at Clark and from another squadron in our Wing at Langley. We walked up to them and asked what the problem was that had caused their rapid and unorthodox departure from the cockpit. No one answered directly. They only told us to go take a look. They all appeared somewhat antagonized and hostile to our approach and questions.

‘I mounted the steps leading to the cockpit and forward cargo area of the aircraft. The plane had been rigged for Personnel Air Evacuation. In this procedure, the C-130 had a series of metal stanchions which clipped into the floor and ceiling and created a U-shaped aisle formation inside the cargo compartment. Using the stanchions for support, a web of heavy nylon straps clipped into them and intermeshed into triple tiered levels of stretcher supports in the manner of the old Pullman railroad bunks. In the aircraft there were 50 or 60 individual stretchers, three levels high, in four aisles around the cargo compartment.

‘Slowly and silently, together with the rest of our crew, I walked down the aisle on the right side of the cargo compartment between the two rows of three stretcher tiers. I took a left turn at the end of the aisle and walked forward to the flight station wall down the second aisle on the other side of the plane, also bounded on both sides by three high stretcher tiers. I noted that the plane was almost at the maximum number of stretchers that it could carry in this rigging assembly. Each stretcher contained one green body bag. In some of the bags the outline of a soldier could be traced horizontally from the feet to the head. In others, the occupant appeared contorted. Some were clearly less than a complete body. One, about the size of a basketball, sat alone on its stretcher, taking up little more than a quarter of the stretcher space. It was held in place by a seat strap. Most of the stretchers had a pair of boots and a dog tag fastened to them.

‘They Were Dead. They Were All Dead! This Was an Airplane Full of Dead Men.’

‘My walk through the darkened aircraft took less than five minutes. During that time I smelled the sickening sweet odour that permeated the entire craft. I noticed it as soon as I entered the cargo hold, but it wasn’t initially overwhelming or disturbing. The longer I stayed in the compartment, the stronger a contaminated sweet portion of the overall odour came to the fore. This smell had driven the aircrew from the plane as soon as the doors were opened after their fifty minute flight. The build-up of this nauseous aroma within the sealed aircraft had made them all nearly airsick. In carrying only a very limited number of bodies in the past, such a smell had never before permeated an entire aircraft as this load did. It was a smell never to be forgotten, but one we would become increasingly familiar with.

‘I exited the aircraft and exchanged words with the flight crew. The bodies were the results of the recent Ia Drang battle in the Central Highlands. All of the dead men were Americans. They had been loaded on the C-130 at Pleiku, the closest main airbase to the battle site and had been sent to Đà Nẵng since it held the only US mortuary in Việtnam at the time. There were two more similarly configured and loaded C-130s coming in to land behind this one. We returned to our airplane where a load of palletized cargo bound for Tân Sơn Nhứt was now ready to be put on. At the other C-130, the rear cargo door had been opened and the body laden stretchers were being put into waiting ambulances. As we took off for Saïgon, we heard the other two planes from Pleiku call in for landing and parking instructions.’9

‘The C-130 was very accommodating to the Tactical Airlift role. It was ugly, slow and not jet propelled. Mounting four turboprop engines, it was capable of carrying 40,000lbs of cargo 2,500 miles. It had floor mounted cargo rails which allowed palletized cargo to be quickly slid in and out directly through the rear door and ramp. In an hour, the five man crew could pull up the cargo rails and put down seats or litter bearing straps. The plane could then take fifty paratroops on an airdrop or carry seventy passengers to a distant destination. In similar fashion, it could also carry fifty hospital patients, each in his litter. The C-130 was fully pressurized and cruised at 20,000 feet at 300 knots. It could take off in 1,500 feet or in 2,000 with a sizable load. It could land and come to a complete stop in less than 2,000 feet and operated easily from 3,500 and 5,000 foot airstrips. It was an allweather, 24 hour a day machine with its own airborne radar and navigation equipment. Ugly, but practical and relatively cheap, the 130 was ahead of its time and a wonderful combination of ‘50s technology suited to the Tactical Airlift mission. Normally it had a crew of five, including a pilot, co-pilot, navigator, flight engineer and loadmaster.’ In March 1966 the ‘Blind Bat’ project relocated to Ubon, Thailand and that same year the 6315th Operations Group control was replaced by the 374th Troop Carrier Wing, later designated a Tactical Airlift Wing. Ronald Edward Dudley, born 28 January 1934, from Roanoke, Alabama flew the C-130A on three tours in Viêtnam. Much of the time, from 1966 to 1969, he served with the 41st Tactical Airlift Squadron, 345th Air Wing flying out of Okinawa in the Japanese home islands.

Lieutenant Colonel Ron Dudley’s C-130A transport crew when he (centre squatting with dark hair) was flying secret missions from Korat Royal Thai Air Force base in Thailand in 1967 during one of his three deployments to Việtnam.

‘Twenty-one days a month my five man crew and I would fly into Southeast Asia in my C-130A. It was the best airplane I ever flew; it was superb. Our general mission was to resupply and support our ground troops. We could handle 100 paratroopers combat loaded or 74 people if you put them in seats. Sometimes I’d fly in small tanks or armoured personnel carriers. I put one personnel carrier into a 1,900-foot strip and three months later I went back in and flew it out. I had some missions over North Viêtnam, but most of my missions were over Laos as a forward air controller. We flew in at night dropping flares at 1,500 feet so out bombers could see the targets. We took part in some secret missions in Laos flying out of the Royal Thai Air Base. At night we’d fly down Highway 1 in Laos and North Việtnam looking for targets of opportunity to bomb. If we found a target we’d call in an air strike. On an average night you would take 100 rounds of 37mm anti-aircraft fire from VC gunners. On the worst night we took just short of 1,000 rounds. Our loadmaster, Sergeant Don Brant, came up with a name for our plane: Super Dud and the Dolighters. This became our call sign until the VC caught on. The fighter planes we worked with would call in and I’d say Good Evening. You’re about to be entertained by Super Dud and the Dolighters. I had to stop using that call sign because the VC, the bad guys, would call on our frequency and say: Super Dud, good to see you. We’re gonna have fun tonight.

During one secret mission over Laos one night the VC antiaircraft unit set up a flak trap. They were waiting specifically for Dudley and his C-130 to arrive. The enemy somehow already had the secret frequency he was given just before taking off from the base in Thailand.

‘When we flew into the area the VC radio welcomed us by saying, Super Dud you have just moved to the top of the money chart. There is now a $250,000 bounty on your heads. We have imported several Number-10 (top) gunners. Tonight is your last night. I’m gonna be rich tomorrow. We had a little problem at the original sight so we moved it eight clicks up the road.

Dudley flew over the designated area and was beginning his decent to 1,500 feet where he would begin to patrol the area for the next six hours. ‘All of a sudden there was a flicker on the ground. I realized immediately what had happened. The VC had lured me into a trap. They opened up on us with five 37mm guns. Lucky for me I was at 8,000 feet when they started shooting at us. If they had waited until I got down to 1,500 feet I would have been a dead duck. I only had to climb 5,000 to 6,000 feet to get out of the range of their guns. It seemed like it took us twenty hours to get out of range. In reality it was only two or three minutes. But during those minutes we could hear stuff from what the enemy was firing at us hitting our plane. We finally made it back to base at 0300. I had just gotten to bed when an aide to Colonel Drummond, our squadron commander, knocked on my door and said he wanted to see me right away. I got dressed and the aide drove me out to the flight line where the commander was waiting.

C-130s being loaded at Phan Rang Air Base in June 1967.

On 13 April 1968 C-130B 61-0967 of the 774th TAS, 463rd TAW with seven crew was landing at Khê Sanh when it suffered an engine failure and suddenly veered off the runway. The aircraft hit six recently dropped pallets, still containing cargo and then continued into a truck and a forklift vehicle before coming to a halt and bursting into flames. The aircraft was damaged beyond repair but all the crew were rescued, although a civilian who was on board later died of his injuries.

‘What happened to you all tonight?’ the colonel inquired.

‘I told him, I got stuck in a flak trap and got shot up.

‘You got 97 holes in the airplane, the commander said incredulously.

‘Yea, but nobody got hurt, I replied.

‘The next night I was right back up their flying.

When I checked in on the radio the same oriental VC voice on the ground said to me, Did you have fun last night?

‘I told him You can take your radio and stick it where the sun won’t hit it.’

In 1967 Dudley and his C-130 was taking part in a test programme in Viêtnam to perfect a low altitude extraction system for equipment they were trying to drop off while under fire or in areas where there was insufficient landing space. ‘I dropped the first extraction under fire at a little Army outpost along the Cambodian Border called Cam Duc. Another plane had flown into the base before me and got all shot up by quad .50 calibre machine guns the VC had at the end of the runway. I came down through a hole in the clouds too steep to escape the enemy machine-guns. Because I was too steep the balled up parachute that was suppose to pull the loaded pallet out the back of the airplane dropped back inside the plane. I had to come around a second time. On the second pass Sgt Brant, my loadmaster, went back behind the hot load that was ready to go, picked up the parachute and tossed it out. Then he stood in the wall of the plane when the pallet was dragged out after the chute opened. The skid went out the back of the plane that was flying 180 mph just above the ground and skidded to a stop within a few feet of the waiting soldiers.’10

The 41st TAS lost two more ‘Blind Bat’ C-130As to enemy action over Laos in 1968-1969. On 22 May 1968 C-130A 56-0477 with a crew of nine captained by Lieutenant Colonel William Henderson Mason was shot down on a flare mission to southern Laos near Muang Nong about twenty miles southwest of the A Shau Valley (thung lũng A Sầu) in Thừa Thiên-Huế Province west of the coastal city of Huế, where another aircraft had reported a large fire on the ground. On 24 November 1969 C-130A 56-0533 a ‘Blind Bat’ Forward air control aircraft flown by Captain Earl Carlyle Brown was orbiting at 9,000 feet in the Ban Bak area to the east of Saravan in southern Laos. The aircraft was above a 4,000 feet cloud base when it was hit by several rounds of 37mm flak and burst into flames, crashing about fifteen miles east of Bạn Talan. All eight men on board were killed. A third ‘Blind Bat’ - C-130A 56-0499 crashed on an attempted three-engine take-off from the small airstrip at Bu Dop near the South Việtnamese border with Cambodia on 13 December 1969. The strip often suffered from enemy mortar attacks and three-engined departures were not uncommon as they were preferable to staying on the ground overnight until spares could be flown in. Three successful three-engined take offs had been made by C-130s from Bu Dop in recent months but the fourth attempt failed.11 The flare-dropping missions continued until 15 June 1970 when AC-130 hunter-killer gunships took over: with electronic detection and imageintensifying night observation equipment and a 1.5 million candlepower searchlight. They were by now better equipped than the ‘Blind Bat’s for the task of identifying and destroying enemy troop and transport convoys using the Hồ Chi Minh Trail.

A C-130E comes in for a landing in January 1968 at the airstrip at Đông Hà combat base, South Việtnam where men of US Naval Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit 301 are repairing the runway. (USN)

On 19 June 1966 after a week of not flying, Captain John Dunn’s crew left Mactan at 9:00 in the morning on their return to the shuttle. ‘We passed through Clark, as usual’ wrote Bill Barry ‘and picked up a load of cargo and passengers for Đà Nẵng and Tân Sơn Nhứt. We landed in Saïgon as the daily replacement aircraft at 6:30 in the evening. We left Tân Sơn Nhứt and checked into the Globe. Unfortunately, the hotel was all but full for the first time and since rooms were short, our crew checked into just two suites rather than three rooms. The two enlisted members stayed in one suite and we three officers checked into another. It was a time for real togetherness. The next day, we headed out to the base about noon but found that our aircraft was being worked on by maintenance. We drew a version of the passenger run as our first mission, but it was four in the afternoon before we got off the ground. We flew clockwise to An Khê, then Chu Lai, Đà Nẵng, then back to Chu Lai because there was a large marine influx in that area all of a sudden. Then we went to Đà Nẵng to pick up a cargo load, which we took back to Saïgon. It was fifteen minutes after midnight when we finally landed and shut down the engines.

‘The next day, we left the hotel at noon and ate on base at the officers’ club. We checked into 130 Ops and were scheduled for a cargo hauling mission with a 4:30 takeoff. Our first stop was the army base at An Khê, where we picked up cargo and passengers. We flew from An Khê in the Central Highlands due east to the coast and then south to a new army base which was being established at Tuy Hòa, a large plain on the coast. To the north of it was a river clearly identifiable on my radar. The base itself, however, was not a good radar target, as the runway blended into the coastal plain and, other than distance from the river, there was nothing to distinguish it from the plain itself. We quickly offloaded the cargo and troops through the back door and ramp with our engines running and were airborne again in five minutes. It was still daylight, but the sun was setting and the field had a low cloud cover over it which appeared to be decreasing in height. It was also lightly raining.

‘It was only a twenty minute flight back to An Khê and we returned there to pick up another similar mixed load also bound for Tuy Hòa. It took forty minutes to get the new load onboard and we again set off for Tuy Hòa. When we got abeam Tuy Hòa this time, it was beginning to get dark due to a combination of the time of day and the steadily increasing cloud build-up and rain around the base. Again, we landed visually, offloaded quickly and got airborne in less than five minutes.

‘Now, with an empty aircraft, we flew 25 minutes down the coast to Cam Ranh Bay, where we were supposed to pick up cargo and take it to Tân Sơn Nhứt. It took us nearly an hour to get offloaded and put a pallet on at Cam Ranh Bay. We then took off and proceeded east for a return to Saïgon. Just after we were airborne, the Cam Ranh Bay ALCE called and told us that things had taken a turn for the worst back at Tuy Hòa and we were to turn around and go back to An Khê for another load to take into Tuy Hòa. As directed, we turned around and flew back to An Khê.

‘It was now dark in the An Khê valley and the base’s approach radar was again out of commission. There was a low cloud layer over the base just a hundred or so feet above our minimums. We first attempted a prescribed letdown, flying with the base radio antenna as our guidance; but when we hit our minimums the runway was not in sight. My radar was working, so we next attempted another radio approach with me giving final guidance and altitude levels using the radar as the primary aid. The base runway showed up well on the radar, but the valley was not all that big and had a 3,000 foot mountain less than ten miles south of the runway. Right next to the runway was a 500 foot high karst hill. We made our approach in a southerly direction, staying to the east of the hill just as we had earlier when I was flying with John Dunn and we evacuated a medical case. In the event of a missed approach, the pilot was to immediately climb to 1,500 feet, thus keeping us above the hill while circling counter-clockwise to avoid the mountain.

‘On our second radar assisted approach, we broke out just in time to see the lighted runway, but we were not lined up with it so we climbed back into the clouds and circled for another attempt. The third attempt was successful. We were on the ground after an hour of shooting approaches to get down in the weather and black night. The flight would usually have taken 25 minutes. It took an hour for the army to load us up with pallets of ammunition and then we were off again for Tuy Hòa.

Quảng Trị US Marine Corps, US Army and ARVN Combat Base on Highway 1 about 8 kilometres southeast of Đông Hà in April 1967.

One of the RAAF C-130 Hercules in 1966 that beat a regular path to Việtnam, transporting troops and supplies and taking the wounded home. (Bert Lane)

‘We were inbound to Tuy Hòa in twenty minutes, but now it was also night over the South China Sea. It was still raining and the cloud layer had thickened. Just as at An Khê, we were just 100 or 200 feet above our minimum approach altitude. Tuy Hòa did not yet have radar or even an approach radio to use for a landing aid. We were cleared for an approach, again using the radar and me as our main aids. The radar, however, did not paint the field at Tuy Hòa; so the approach was planned as a turn so many seconds after we came abeam of the river, which sat a half mile to the north of the Base. The river did give a strong radar return. Tuy Hòa sat just inland from the coast and the nearest mountains were ten or fifteen miles east of the runway. Our missed approach plan was to climb straight ahead to 1,000 feet and then circle to the south and back out over the ocean for another attempt.

‘On the first approach, we let down over the ocean in the dark and flew south, 90 degrees off the heading of the Tuy Hòa runway. At 1,000 feet, we couldn’t see anything on shore because the rain and cloud layer had blocked out all light. Twenty-five seconds after the radar showed me that we were abeam the river we turned to the runway heading. I corrected the heading to make up for drift, which read out on the Doppler above my desk. We then descended at 150 feet per mile, hoping to break out of the clouds in time to see and line up with the runway. On the first attempt, we didn’t break out by the time we hit our minimums at 500 feet. We began our go-around turn and suddenly, off to the right, we could see three lights or flare pots set up on the extremities of a barely visible runway. Two lights marked the approach end and the last light sat in the middle of the runway’s far end.

‘We climbed back up to 1,000 feet and proceeded out over the ocean and repeated our approach pattern. This time we turned twenty seconds after passing the river on radar. We hit 600 feet altitude and suddenly broke out of the clouds and rain. In front of us, in good visibility were the three lights perfectly aligned but as we moved in closer, the lights begin to shift. Suddenly the three evenly spaced lights were now bunched to the right. We weren’t lined up and the light at the far end moved toward the light at the right front. We now initiated another missed approach. Three lights of approximately equal size and intensity can take on numerous designs and undergo rapid shifts if you are not lined up exactly with them. We all knew this from having practiced numerous night paradrops where the drop zone was marked by the same light pattern as the Tuy Hòa airbase. But we had just learned the lesson again in the rain and fog.

‘Our next approach followed the same pattern, except we turned at 23 seconds past the river. Now we broke out again at 600 feet, but this time we could clearly see that we had lined up with the runway. Again we were on the ground after an hour in the air on what would normally have been a 20 minute flight. The army rapidly unloaded the ammunition pallets. Artillery was firing just off to the side of the parking area as we turned back on the runway and proceeded back to An Khê. It again took two tries to get on the runway at An Khê due to the low cloud base and the lack of any nighttime approach aid except our own radar.

‘At 1:15 in the morning, we took off with another load of ammunition. As we approached Tuy Hòa from over the ocean, we could see that the rain had stopped and the cloud layer had thinned out and lifted. We proceeded in and landed visually with no further problems, using the three marking lights as our landing reference. The army was still firing artillery off as we unloaded, but the pace was much reduced from the previous landing. After fifteen minutes on the ground, we were unloaded and back in the air.

‘An hour later we landed at Tân Sơn Nhứt and called it a night at 2:30 in the morning. The combination of the bad weather at both landing sites and the lack of any reliable approach aid other than our own radar made this an interesting and hairy night of flying. Each night-time approach was hazardous. We could have all used a drink before turning in; but the club was closed, so it was back to the Globe for an attempt at a night’s sleep. ‘That evening we were again airborne at 9:30 and shuttled with cargo between An Khê, Đà Nẵng and Chu Lai. We got back into Saïgon at 5:00 in the morning. On landing we were told that our crew had been submitted for a medal citation to each receive a DFC for the previous night’s flights into An Khê and Tuy Hòa.

‘That was the second DFC I was recommended for. I never got either one.’12

By the summer of 1966 PACAF’s permanently assigned C-130 strength stood at twelve squadrons and this reached a peak of fifteen units early in 1968 with three deployed TAC squadrons on TDY tours. Thus in February 1968 a total of ninety-six C-130s were stationed in Việtnam: the huge port complex at Cam Ranh Bay was home to fifty-one C-130As and -Es; Tân Sơn Nhứt accommodated twenty-seven C-130Bs; Tuy Hòa had ten C-130Es; and Nha Trang, eight C-130Es. By the end of 1971 only five C-130 squadrons remained in the Pacific, although the VNAF airlift force operated two squadrons. Two squadrons were equipped with C-130As just before the 1973 ceasefire.

KC-130F BuNo148892 of VMGR-152. This Hercules was delivered to the USMC in May 1961. In around 1975 it was transferred to VMGR-234 at NAS Glenview, Illinois. In January 1994 it was transferred to VMGRT-253 at MCAS Cherry Point, North Carolina. In October 1997 it was permanently withdrawn from use and in November it went to the Fort Worth Joint Reserve Base at Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas and used as a maintenance trainer.

During the spring and summer of 1966 the 1st Brigade, 101st ‘Screaming Eagles’ Airborne Division, was transported on five occasions by the C-130s; each deployment involved 200 Hercules lifts and each operation was mainly resupplied by air. Operation ‘Birmingham’ was a four-week air deployment into Tây Ninh province beginning on 24 April in which the C-130s flew fifty-six sorties into the 4,600 feet airstrip, delivering supplies and munitions around the clock. (At the same time they also supplier, the airborne brigade at Nhơn Co.) By the time ‘Birmingham’ ended on 17 May, the C-130s and C-123s had flown almost 1,001 sorties and delivered nearly 10,000 tons of cargo for the 1st Cavalry Division.

The USMC also played a part in airlift operations. By July 1966 the road network north of Đà Nẵng was in a state of disrepair - though in any event, Communist activity had made transport by convoy extremely hazardous, while port facilities and ail fields near the DMZ were poor. Therefore the only way to resupply the marines in country was by air. USMC KC-130Fs backed up by USAF Hercules, flew more than 250 lifts into a red dirt strip at Đông Hà . Further C-130 flights to the area delivered large quantities of materials and PSP steel matting and the airstrip was later resurfaced; a second all-weather strip we opened at Quảng Tri.

In late June 1966 Captain John Dunn’s crew were nearly halfway through their assigned thirteen month tour. ‘On 27 June’ wrote navigator Bill Barry ‘we were up at 3:00 in the morning and again took the crew vehicle to the base. Same routine as the day before, but this time the airplane worked and we were off to the small runway at Sông Bé and another Army ‘search-and-destroy’ operation. Sông Bé is forty miles North of Saïgon. The bare runway with no parking area sat just adjacent to a 200 foot mountain in an otherwise flat plain. Lộc Ninh is fifteen miles due west of Sông Bé and both sit within ten miles of the Cambodian border.

South Việtnamese troops leaving a battle zone after landing in C-130E 63-7883. This aircraft was delivered to MAC in June 1964.

South Việtnamese troops milling around C-130A 56-0489. This Hercules was delivered in May 1957 and after service in TAC was allocated to the SVAF in November 1972. It was one of many aircraft captured by the NVA in April 1975.

‘All day we made seven shuttles between the two sites, hauling army troops and equipment in rapid onload/offload operations where the troops and vehicles rolled on and off through the rear ramp and door while our engines were running. It was hot and dusty and the aircraft’s broken air conditioner would not have been of any use on the short flights anyway. Halfway through the day we returned to Tân Sơn Nhứt for fuel and an hour on the ground. We finally landed back at Tân Sơn Nhứt for good at 10:30 that night. We logged five and a half hours of flying time in an eighteen and a half hour day with twelve separate individual sorties flown.

‘The variety of loads that we were carrying was in some ways funny and in others amazing. Probably only the C-130 could safely accommodate them all and that is in spite of the many errors and miscalculations that kept them from having any kind of ‘ordinary.’ Largely for these reasons, the Tactical Airlift mission and its crews became known as ‘trash hauls and trash haulers’ since, like garbage men in the states, they would haul anyone and anything.

‘When we picked up a load from the army, it was their responsibility to identify the load and correctly indicate its weight and contents. Many army loads included large metal Conex containers, which they used to store everything from ammunition to the personal belongings of units which were moving or going into the field. We were used to moving the containers to storage areas or to the deploying unit’s next location.

‘Many, many times the loading data for the containers gave an incorrect weight for them. On other occasions the weight was given for an empty container when in fact the container was loaded to the fullest with something or other. Sometimes it became apparent that the container was mislabelled when the forklift putting it on the aircraft had trouble lifting the listed weight. At other times, several palletized containers might be loaded and each of them would weigh more than listed, but not enough to, individually, indicate that something was wrong.

‘The same could be said for many of the army trucks, jeeps and trailers that we loaded and carried. Our loadmaster planned each load according to the listed weights so that the airplane maintained the best centre of gravity for performing according to standards for both flying and takeoff and landing. When the actual load was widely off from what was listed, the aircraft would either tilt on its tail or give indications of sinking on its front nose wheel. Many times we had to raise our legs to get in the crew door on the steps which should have been resting comfortably on the ground. On occasion I’ve even had to physically climb up the steps to get in the door. Thank God the C-130 handled so well and was so forgiving. ‘One load that we had was a five pallet shipment of army boots packed in large cardboard boxes. The boxes were oversize commercial moving containers about four feet square by five feet high. They were stacked two high and tied down so that twenty or so boxes were on each pallet. The pallets had been sitting in the Tân Sơn Nhứt cargo storage hangar for some time. Once we were in-flight carrying the boots to an army base, several of the boxes collapsed inward or caved in. Some were completely empty and others had half a load of boots in them. Between their original destination and our flight to their final one, they had been looted. I doubt if the whole load had more than one-quarter of the number of boots in it that we cited on the loading document.