4.

BEWARE OF THE CHICKENS

As I stare into my old toybox, I’m trying to figure out whether to choose a disguise or pretend I’m coming down with a fever. My phone vibrates in my pocket, but I don’t bother checking. Harriet keeps sending links to UFO articles and texts, begging me to meet her tonight in a paddock, somewhere near school. She wants to get started. Should I meet her without telling anyone? In the dark? There could be potholes, barbed wire, a risk of tetanus and who knows what else? I agreed to fake UFOs, but maybe we need a safety plan first. My hand slips into my hoodie and I’m about to text an excuse when Mum sticks her head around the door.

‘I had an idea,’ she says, arms full of laundry.

‘What’s that?’

‘Dad’s grave. If we have to leave we could take photos and make our own special memorial. I’d glue on magnets, so we could keep it on the fridge. I saw something on Pinterest … I mean, it’s an idea.’

I can’t help staring. She wants to replace Dad’s grave with a homemade fridge magnet? Mum stares back and then shakes her head. ‘Yeah, you’re right. I’ll think of something better. Sorry, it’s been a long day.’

I take a deep breath. Every day’s a long one for Mum and the lines around her eyes look deep. Ever since Dad died she’s been working longer hours at the poultry farm and there’s no one to help with budgeting, or with fixing the TV aerial, which keeps falling off the roof before important football matches. That’s a lot of pressure on one grown-up.

‘No worries. Hey, Mum, is it okay if I hang out at Alex’s until dinner?’

Mum blinks. ‘Alex’s house? You haven’t visited there for ages.’ She watches my face like she expects me to say something else, but I’m not sure what. Guess she’s noticed I don’t get invited anywhere, much. Has she been worried? I hope not, because I don’t care. I’ve been sorting out more important stuff than playdates, like cataloguing my first aid kit and researching ways to sterilise our family’s toothbrushes.

When it’s obvious I’m not going to answer, Mum clears her throat. ‘Okay, dinner should be ready by seven-thirty; we’re eating late because Ellie has netball practice. Oh and I’ll give you a clue for tonight — famous kings in history. For extra ice cream, guess whose face is on the most mugs in Britain?’

It’s not hard. Mum’s BA in History specialised in one person. I think her professor had an unhealthy obsession with royalty.

‘Henry the Eighth. All your questions on royals are about Henry the Eighth.’

‘Correct.’ She grins and heads back down the hallway, humming an eighties rock song about a saint called Elmo who started a fire. Taking a deep breath, I bend over the toybox and search for a disguise. Poor Mum, she can’t fix everything. She’s busy trying to feed us, pay the bills and teach me history.

If I want to save the school, I need to sort this problem on my own.

Alex and I stand in the dark behind Mrs Jones’s old milking shed, streetlights throwing shadows across the fences. Harriet’s looking at me like I’ve landed from Mars, which is technically appropriate but makes me feel awkward. Harriet folds her arms and says, ‘Your shoes are glowing and … seriously? What’re you wearing?’

I stare down at my old Halloween costume. ‘It’s a disguise, of course. I don’t want to be seen. If I get caught Mum will kill me.’

Harriet snorts. ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’

‘What?’

‘Lucas, you’re dressed as a teenage mutant ninja turtle.’

‘So? I didn’t want anyone recognising me.’ My cheeks burn under the green mask: it was all I could find in my old toybox. ‘Well, what about you guys? You’re both dressed in black footie gear, so what’re you? Trained ninjas?’

Alex shakes his head. ‘Wearing black helps us blend into the night. You look like you’re going trick or treating! Still, at least you’re not wearing that fluoro safety vest or reflective knee straps.’

Truth is I couldn’t fit the vest over my fake shell and I shrug. ‘What’s wrong with wearing my vest? It’s dark on the roads.’

Alex sighs through his teeth and shakes his head. What did I say? Lately, I’ve noticed weird moments when Alex seems angry and then, two seconds later, he’s fine again. Dunno why. We’ve never had an argument, so maybe I’m imagining it. I hope so.

He takes a deep breath. ‘Never mind, it doesn’t matter. Look, did you remember to tell your mum you were working on the assignment at my house?’

‘Of course.’

‘Good, Harriet did, too, and I told Mum we were working in my tree house by the shearing sheds. She’s making dinner, so we’re covered for about half an hour before she comes looking.’ He glances over his shoulder into the darkness of Mrs Jones’s fields. ‘We should be fine, everyone just keep an eye out for chickens, okay? If we come home covered in peck marks and feathers it’ll look suspicious.’

Nodding, I flick my torchlight across the grass. Mrs Jones must be the oldest person in town and she doesn’t keep her property up, including her coop with the broken doors. When old people can’t take care of their chickens anymore, you call the birds ‘free range’ and ignore the fact they’re roaming through everyone’s backyard and nesting under your classroom. Trouble is, uncared-for chickens do weird stuff like chasing kids across school crossings or launching surprise attacks from under the P.E. shed. However, you can’t turn Mrs Jones’s pets into Sunday roasts because no one wants to upset an old lady, so they’re treated like protected wildlife. Most of them still live on her property, which is half the reason why I’m wearing this costume. My knees need protection from feral birds.

Come to think of it, why did Harriet pick Mrs Jones’s back fields? I’m not sure this is the best place to fly my kite, not with the risk of chicken attacks. I flash my torch along the bushes, checking for any sign of life, and ask, ‘Hey guys, are you sure this is safe?’

Nobody answers.

Alex clears his throat and asks, ‘Harriet, did you bring the big torch?’

‘Yeah, I borrowed it from our garage.’ She holds up the plastic lantern. ‘Where’s your dad’s equipment?’

That sounds weird. Before I can ask what equipment, she’s hurrying ahead and whispering, ‘I left Mum’s weed whacker behind the shed. Come on, let’s move fast, we don’t want to get caught.’

‘Hang on!’ I say, chasing after them. ‘What do we need gardening tools for?’

They’re already walking across the dark field, following the light off Harriet’s torch. Next to me, Alex mutters, ‘The corners, of course.’

‘Well, I’ve got my kite in my backpack. Guys … what’re we doing?’

Again silence, but then Alex sighs. ‘We had an idea. You can fly the kite, while we cut Mrs Jones’s grass. She grows it super-long for hay season, so … um, you’ll see.’

Is he serious? I point across the field, which is barely visible from the distant streetlight. ‘I dunno if aliens would be out mowing people’s lawns. I mean, who would travel millions of light years just to tidy someone’s backyard? It’s not like aliens need pocket money.’

They both stop and look at me. I can’t see their faces but my gut tells me something’s wrong. Harriet sucks in a deep breath. ‘Remember that stuff I emailed you about crop circles?’

Truthfully? When I saw the seventeen-page attachment arrive in my emails, I hit delete and figured she’d explain later. In my defence, I was busy reading about burn treatment, but maybe I should’ve read her message. ‘I kind of skimmed a few pages, can you remind me?’

‘Seriously? Why did I even bother?’

‘Harriet,’ says Alex. ‘Just tell him.’

‘Okay, fine. I’ll give you the short version. Scientists find crops all over the world, flattened into the shape of circles. Some people think it’s caused by disc-shaped UFOs landing in the night.’ She turns away and starts stomping across the wet grass. There’s a distant fluttering through the darkness. I’m hoping her noise scares off the chickens. ‘Anyway, we have to lift our game. No one really believes Mrs Jones saw UFOs … Well, no one except her and a farmhand. We need proof. Hey, are you guys following me or not?’

I stare at Harriet’s moving shadow. She’s the teacher’s pet and class monitor. None of this makes sense.

‘Harriet,’ I whisper loudly into the darkness. ‘We’re on private property. Aren’t you worried about getting into trouble?’

She stops for a moment, but then shrugs. ‘It’s just cutting someone’s grass. That’s not a crime and we’re not getting an A by doing nothing, are we? Come on.’

Okay, now I understand why she’s breaking rules. Harriet will do anything to get first in class. But still, they can’t be serious? ‘Crop circles, Harriet? Who would be dumb enough to believe in those?’

Alex pulls the football scarf around his neck. ‘They’re really popular, it’s all over the internet on those conspiracy pages. We’ll show you later, but let’s hurry up. It’s freezing out here.’

I shake my head but start walking, almost breathing down their necks. ‘Guys, it doesn’t make sense. I mean, if aliens were smart enough to travel across the galaxy, why wouldn’t they use empty spaces like the airport? They’d need to preserve food sources for an invasion, not ruin perfectly good crops.’

Alex shrugs. ‘Anyone who believes in aliens can’t be that smart, right? And look, we’re not touching anyone’s crops. We’re cutting overgrown grass, it’s no big deal.’

‘Okay, but why didn’t you tell me … ? Oh. Right.’ Harriet’s torchlight stops over a rusty mower with the words ‘industrial strength’ scribbled on masking tape across the handle. No wonder neither of them mentioned their plans. ‘Harriet, these mowers have sharp blades.’

‘No kidding. How else would they cut grass?’

I fold my arms. ‘Did you know fifteen per cent of outdoor injuries are related to garden appliances, mostly because people misread the labels?’

Harriet sighs. ‘We’re more likely to die standing around listening to you moan. We’ll catch the flu or whatever we’re in danger of catching at night. Mum’s always going on about getting sick.’

Statistically speaking, she’s got a point. Also, I’m not keen on looking like a baby and I’m not about to wrestle a sharp tool off her, so I shrug and say, ‘Well, I guess it’s your choice.’

‘Yep, it is.’ Harriet reaches down for the throttle. ‘Relax, you don’t have to do anything. Keep watch and we’ll work the mower, okay?’

We’re several paddocks away from Mrs Jones’s house but sound travels far on a quiet night. The motor starts like a hacking cough and we all jump, glancing over our shoulders. Concentrating hard, Harriet starts by mowing a square which gets bigger, then she nips around the corners, turning it into a circle. I flick my torch around, whispering helpful instructions like, ‘Look out! Keep your feet well back from the guard … Don’t lose your balance, stop tilting forward.’

‘I’m not an idiot! I’ve done this before.’

Of course, most farm kids operate basic machinery by the time they’re ten. But she’s missing my point. ‘Overconfidence leads to injuries, Harriet. It says so on keepsafekids—’

Bright light slashes across my face. The words freeze in my mouth. What was that?

‘Who’s there?’ An old woman’s voice floats over the field.

My heart belly-flops into my stomach and Alex says a word which would get him banned from screens, if his mum ever heard.

‘Mrs Jones!’ hisses Harriet over her shoulder. ‘Run!’

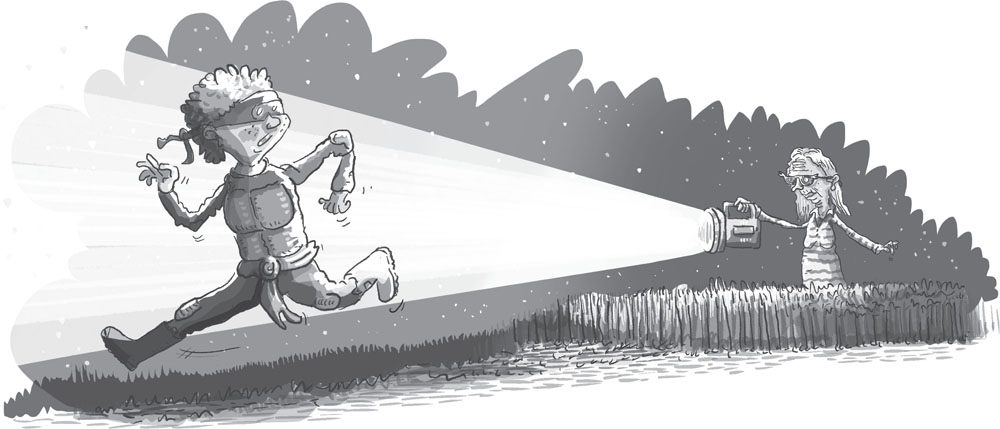

Alex gasps, dragging the mower with both hands into the darkness, probably heading for the gate. The voice comes again, calling through the long grass. A beam of light flashes sideways across the paddocks, searching for Alex and Harriet, but they’re already sprinting in different directions. Turning, I follow the squelching sound of Harriet’s sneakers through damp grass. Something bony bumps against my legs. A chicken. Feathers fly, birds shriek and — splat. I’m falling headfirst into the soft dirt.

My heart slams into my ribs. I’m busted. My chin hurts but … where’s the chicken gone? Visions of being pecked to death by feral guard chickens rush through my head as I drag myself off the ground. Too late: Mrs Jones’s torchlight moves towards me, floating over the grass like a tiny ghost. I back away towards the fence, but the torchlight moves faster, freezing against my face.

I’m blinded.

Mrs Jones gives a small scream.

Is she hurt? Did she trip over some machinery? Did wild chickens attack her knees? Mrs Jones calls out, her voice wobbling on the night air, ‘Who’s there? What do you want?’

For some reason, she’s not coming any closer, maybe because she thinks I’m a dangerous criminal, so I shout, ‘We don’t want anything! I know we’re not supposed to be here, so we’re going! I’m really sorry!’

Her torch stays aimed at my face. ‘But what are you doing here?’

Just in time, I remember her awesome apple trees, down by the gate. Everyone raids those trees, it won’t sound odd and she can’t eat much fruit — she must be nearly ninety. ‘We’re here for the apples. Hope you don’t mind. We just got really hungry.’

No reply. Maybe she’s thinking my answer over, trying to decide if it’s worth prosecuting underage fruit thieves. Wish I’d come up with a better reason, but it sounds heaps better than telling her we’re faking crop circles without permission. Again, Mrs Jones’s voice trembles across the paddock. ‘Don’t you have apples on your planet?’

Wait a minute.

Is she serious? Mrs Jones’s ancient and can’t see well. I’ll also bet she’s never watched an episode of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in her life. It’s crazy, totally impossible, but … does she think I’m an alien?

Well, I can’t say ‘No, it’s Lucas O’Brien from St Michael’s Lane — you know my mum ’cause she delivers your Meals on Wheels every Friday.’ We’d all get into serious trouble. Swallowing hard, I take a step backwards and shout, ‘You’re right, we don’t have any fruit … not where I come from.’

Well, that’s sort of true. Our apple tree never recovered after the last frost and Mum won’t buy groceries until Thursday. Holding my breath, I’m hoping Mrs Jones can’t recognise my voice, when she calls back, ‘Quality manure, that’s what you need. We’ve got plenty here, so help yourself. You can’t grow decent fruit trees without the proper nutrients.’

‘Um, thanks. We might take some with us. I’ve gotta go.’

Wow, this is ten different kinds of strange. Everyone says Mrs Jones should be in a retirement village. She definitely shouldn’t walk through fields at night, risking potholes and talking to imaginary aliens. I need to go home, right now.

‘Wait!’ she calls.

Something flutters in the darkness, probably another killer chicken. Stumbling, I start hurrying towards the fences. Behind me, she calls again, ‘I don’t suppose you could take me with you? I’ve never travelled much and well — look at me — I’m not getting any younger. If I don’t go now, when’s a good time?’

‘Errr, no, sorry!’ I shout over my shoulder. ‘The spaceship isn’t kitted out for old people. No ramps or magnifying glasses.’ My mind runs faster than my feet, trying to think of excuses. ‘Seriously, there’s no bingo or chocolate biscuits. Nothing you’d like.’

Was that a squawk, somewhere on my left? Didn’t I read something about chickens carrying bird flu? Bet it’s contagious.

She sighs. ‘Well, fair enough. I suppose you come in peace?’

‘Yes,’ I call back. ‘That’s it, we want world peace, apples … and your manure.’

‘You sound like those Miss World contestants, always banging on about wanting to solve wars but never actually getting into politics.’ Her voice grows nearer and I hear a faint sniff. ‘Come to think of it, they’re probably aliens, too. I mean, they’re all very tall. It’s not natural.’

Is she following me? She’s quick, for an old lady. What should I do?

‘Look, you need to stay back because …’ Why do people keep their distance from each other? What’s a good reason? Oh, I know! ‘I might be contagious. You know, we have different germs on our planet. You won’t have any immunity.’

‘Oh.’ She stops moving. ‘I never thought of that. I’ve got to be careful at my age. One good dose of the flu and I’m on antibiotics for weeks.’

‘Right, good point. Well, it was nice talking but I’d better go.’

‘All right. Well, thanks for coming. No one’s going to believe me. Actually would you mind waiting here?’

Before she asks for a photo, I sprint towards the fences, holding my breath and hoping there’s no chickens in the way. I throw myself at the wooden posts, one foot on the railing while the other pushes me off the ground like a rocket. Tumbling forward, I almost flip over the fence and land with a thud on the clay ground. A torchlight flashes over my head. Gasping, I leap to my feet.

‘Relax, it’s me.’ Alex’s voice makes me jump, but then I suck in a deep breath of relief. He flicks his torch downward, showing me his bike with the trailer already hooked onto the back. Harriet’s weed whacker pokes out the side.

Harriet peels up beside him on her mountain bike, snapping, ‘Where’ve you been, Lucas?’

‘I — I almost got caught. She’s not far behind.’ I grab my own bike off the fence and leap onto it, my heart still bouncing against my ribs like a basketball. Trying to stuff my helmet over the mask, I push against the brake.

Harriet whispers loudly, ‘Good thing you’re wearing a mask.’

‘Um, I’m not so sure about that.’

‘What? Why not?’

But there’s no time for explaining, so I lean forward and pedal off into the darkness. I just hope Mum never finds out. She’ll kill me, for sure.

‘You’ve got to be kidding,’ says Mum, passing the chicken and mushroom pie around the table. She waves a large spoon at Ellie, slopping gravy onto the placemats. ‘It’s bad enough that Lucas was late for dinner, I’m not taking any nonsense from you, too. Now eat up quickly. The Chase starts in fifteen minutes and I don’t want to miss the start.’

Ellie sighs and looks up at the roof. ‘Mum, I’m sorry but I’ve made up my mind.’

‘You’re not becoming a vegetarian. End of story.’

‘Yes, I am.’

Uh-oh, Dad? Did you see that? Mum’s cheeks changed colour — we’ve gone to red alert on both sides, and you know what that means. A nuclear meltdown fast approaching. Everyone save yourselves!

But Ellie sits there, arms folded and staring at the ceiling like she doesn’t know the code.

Mum’s voice grows quieter. ‘Do I need to remind you that I work in a chicken farm? When you leave home you can get a job and put whatever food you like on the table. Until then you’ll eat what I cook.’

Ellie stares at her plate. ‘But what about those poor birds?’ Steam rises up from the plate, fogging her glasses and Ellie pulls them off. Drying them on her T-shirt, she shakes her head. ‘And since you started doing longer hours I’ve been cooking way more, so—’

‘Don’t start.’

Ellie takes a deep breath, like she’s about to go under water.

Mum shoves the pie at me. Digging my spoon into the bowl, I scrape the bottom and it comes up black. ‘Actually, Mum, maybe you should cook a little more. Seriously. Food poisoning causes hundreds of deaths every year and keepsafekids.com says—’

Ellie points her knife at me, cutting off my sentence ‘No one’s talking to you.’ She waves the knife back at Mum. ‘It’s all that trivia stuff you do with him. He’s become good at memorising boring facts like one million ways to cover us all with bubble wrap.’

I pull a face at the knife. ‘You know nearly forty per cent of lacerations are caused by household appliances and half of those involve cutlery.’

Ellie lowers her knife, but she’s still watching Mum. ‘See? What’ve I been telling you? He’s not getting any better.’

I’ve no idea what she’s talking about; I haven’t been sick since last winter. But Mum gives me a long look, glancing up and down my face like she’s checking for signs of a rash. Then she takes a deep breath, her cheeks start fading and I almost hear Dad whispering, ‘We’re downgrading our threat to Code Pink. All personnel stand down.’

‘No one’s getting hurt with knives, okay? Lucas, please, stop worrying, it’s getting exhausting. Nothing bad will happen, in fact the biggest health risk around here is that vest you’re wearing. When did you last clean it?’

Ellie mutters, ‘I think he’s sleeping in it.’

Now that’s spectacularly unfair. For a start, I sponge my jacket every night, though I can’t get out every stain, and I don’t sleep in it. Well, not on purpose, sometimes I forget to take it off before bed. Secondly, thinking of possible disasters prepares me for anything. I wouldn’t call that worrying, I’m being organised.

‘Seriously though, Mum, we could make our house safer. Our back step’s got a huge crack and wobbles when we stand on it. There’s some great tips for danger proofing your house on keepsafekids.com.’

Mum shakes her head. ‘There’s nothing wrong with our back step, your dad made it himself.’

I glance at Ellie and her fingers tighten around the knife. Dad made lots of stuff which keeps falling apart, but Mum insists the doorframe will fit when ‘the damp season passes’, she’s happy with the painting which hangs lopsided, and the bush Dad planted by the back door isn’t dying, it’s just ‘fading around the edges’.

Ellie glares at Mum and then bursts out, ‘Mum, we can’t keep everything the same forever!’

Mum just stares at Ellie, until my sister takes a deep breath like she’s trying to suck back her words. ‘Look, can we please talk about food again? Vegetarianism, remember? It’s going to happen, so you can all get used to it.’

Mum sighs and leans forward, silver strands falling over her face. She blinks before tucking a handful behind her ears. Mum wears hair nets at work so she always looks surprised when hair slips in front of her face. It’s like she’s forgotten she has any.

‘Okay,’ Mum says, her voice quiet again. ‘Ellie, I hear you, but I’ve had a long day. I just can’t take this right now. Let’s talk about this vegetarianism another time.’

‘I’m sorry, Mum, but I can’t wait. It’s my school project.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I said it’s for my school project, we’re supposed to be protesting something for topic studies. No, I’m not making stuff up, so don’t look at me like I’ve done something wrong. Ask Lucas, it was his idea.’

‘Mine?’ My voice squeaks. ‘No, it wasn’t! We were just talking about saving the school and writing letters … Honest, Mum! I didn’t know she was going to give up meat.’

Ellie shrugs. ‘Fine. Who started this isn’t the point. What matters is I’m not eating any more chickens. End of story, okay?’

Mum’s head swings between us and then she throws up her hands. ‘Fine, Ellie, you can eat soup until you’re eighteen, because that’s all we can afford. I’m not buying fancy tofu burgers when we get half-price chickens and that’s final.’

Ellie pulls a face but reaches for the boiled beans with both hands, like she can’t wait to try more. ‘Okay by me.’

Mum turns towards me. ‘And as for you—’

She just shakes her head and I can’t stand seeing her unhappy, so I say, ‘I won’t do the school project, Mum. Not if you don’t want me to do it.’

‘Of course you can do schoolwork.’ She sighs again. ‘But when you get an idea in your head there’s no stopping you, Lucas. Look, I don’t want to sound unfair. It’s been ages since you did anything over the top and these days you’re very …’ for a second, Mum seems lost for words, but then she settles on — ‘safety conscious. But this family has had all the drama it can take. I mean it, Lucas, I don’t want to hear about anything dangerous. Understand me?’

‘I hear you, Mum.’

Which isn’t really lying because I did hear her. But I didn’t say ‘yes’ because I can’t make promises about not getting into trouble. Still, if I’m saving our school, keeping us near Dad’s grave and promoting tourism for the town, isn’t that being responsible? If you ask me, my project group is taking responsibility for everyone.

But somehow, I don’t think Mum will see it that way.