12

MY EGG-CELLENT PLAN

Hey Dad — I could use a hand, right now. Do you know Saint Jude? Your funeral service was at Saint Jude’s church and I remember Nan saying he’s the patron saint of lost causes, so people pray to him when they’re desperate. Could you ask him for a favour? I mean, you must’ve met him in Heaven and he kind of hosted your funeral, so I’d say he’s the right man for the job.

You see, I dunno if my plan will work.

‘We’re here,’ gasps Harriet, interrupting my conversation as she slams on her bike’s brakes. ‘Now what?’

After several minutes of mad pedalling, we’ve reached the poultry farm again. More people have arrived and I’d say half the caravan park must be here. Tourists walk past the fences with cameras or poke their noses into recycling bins, almost like they’re hoping to find dead alien bodies. Talk about weird. Most of them look curious rather than angry, unlike Mr Winter. His face burns red around the edges like a crater ready to explode.

‘Just follow me.’

Harriet mutters, ‘I’m not sure this is a good idea.’

‘Shh,’ I whisper, as we move through the crowd. ‘It’s too late to change your mind now.’

‘But look — over there!’

Spinning around, I spot the SUV couple, pressing their fancy cameras against the wire fence. Harriet turns so pale her freckles look like cornflakes floating in milk. Clearing my throat, I ignore my thumping heart and pat Harriet’s shoulder. ‘It’s okay, we’ll stay far away from them. Remember they don’t know about us, and we’re not doing anything with aliens. We’re here to save chickens.’

‘T-true. Okay.’ She nods but keeps glancing over her shoulder. She doesn’t need to worry, no one’s watching us. They’re busy staring at the big barn.

My backpack moves against my shoulder and I take a deep breath. ‘Okay, remember, don’t do anything until I say “go”, okay?’

‘I’m not sure …’ She glances at her own backpack, banging left and right on her shoulder.

‘You can do this, Harriet. Just think of the project. Imagine getting an A.’

She curls her hands into balls and nods. Nobody notices the clucking coming from our bags. Catching Mrs Jones’s chickens wasn’t easy: luckily I was wearing two layers of rubber gloves from the poultry farm. Letting the birds go should be a piece of cake, especially as I’m wearing knee straps under my tracksuit pants.

Heads down, we sneak into the middle of the crowd, pushing past a couple of weird-looking guys with long beards and tie-dyed trousers. No one seems interested in a couple of kids. We crouch on the grass and unzip our bags.

Gently, I push out one of Mrs Jones’s chickens onto the ground and Harriet does the same with her backpack. Taking another deep breath, I remind myself that we’re not doing anything wrong. We’re just letting out two wild chickens, who will find their own way home. Harriet mutters, ‘I don’t see why we couldn’t have taken one of Mrs Jones’s chickens in the first place, instead of rescuing one from the poultry farm.’

I just shake my head. It had to be a poultry farm chicken. Ellie wants to save a chicken from captivity and Mrs Jones’s birds are already free. But now’s not the time to explain.

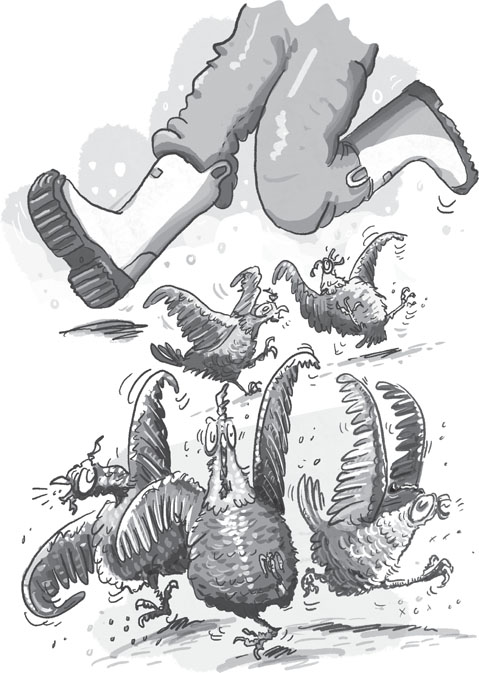

The birds stumble towards the grass. I thought they’d feel happy about being released from stuffy bags, but no — they start squawking and flapping into the air. One pecks me hard on the arm. Caught by surprise, I give a yelp. Several people turn around as Harriet shouts ‘Chickens!’

No one looks very interested. After all, we’re outside a chicken barn. People expect that sort of thing.

So I start waving my arms and shouting, ‘Look! Someone’s let the chickens out!’

Voices start muttering across the crowd. ‘Did I hear right? Is someone selling chicken sandwiches? I wouldn’t mind one.’

‘No, someone said the chickens were out.’

‘Out? Did you hear that? Someone said the aliens are OUT!’

‘Does that chicken look like an alien to you?’

Clearly they’re not getting the message. Neither are the poultry farm workers. So Harriet and I push through the crowd towards the fence, shouting ‘Chickens! Some protestors let out the chickens — they’re everywhere!’

Some people look confused, no one can tell how many chickens are loose. A few people stand on their toes, maybe hoping to catch a glimpse of bird-shaped aliens strolling past the fences. But Mr Winter flings open the gate, rushing into the crowd and shouting ‘GET AWAY FROM MY CHICKENS!’

Mrs Irvine yells into her phone and the barn doors swing open as workers race out. Trouble is, wild chickens aren’t keen on people running towards them. As the first staff members run into crowd, one of the hens darts between an old lady’s legs and she falls over, straight into the arms of Mr Winter. The other chicken screeches and flies up into the air, then lands on the head of a girl with long braids. She screams and dances around the carpark with a chicken on her head, shrieking ‘Get it off! I’m a vegetarian!’

Which makes no sense, ’cause no one asked her to eat it.

‘Harriet!’ I grab her arm, pointing at the side gates. ‘I’ve gotta get back inside. Make a run for it and I’ll meet you by the bus, okay?’

Harriet nods, already sprinting in the opposite direction and shouting, ‘Somebody call security! There’s more chickens over here!’

Everyone starts diving and pushing, trying to avoid birds they can’t see, while more factory staff run into the crowd. Taking advantage of the confusion, several protestors rush through the open gate, hurrying towards the main barn.

Mr Winter doesn’t seem to notice. Instead he’s hollering and chasing the nearest chicken. Mrs Irvine follows but she only supervises the workers and does the accounts and you can tell she’s not sure how to catch birds. She runs after them, holding out her arms like she hopes they’ll leap into her hands.

Mum races past the fence, waving at me. ‘Lucas, I don’t know what’s happening! Get Alex and go home! I’ll call you later!’

‘Uh, okay!’

Running towards the side gate again, I punch in the code and sprint across the courtyard. Flinging open the barn door, I almost slam into a group of strange men wearing The X-Files T-shirts. They’re staring at the cages with wide-eyed expressions and holding up camera phones. Behind them I spot Alex, who throws me worried looks.

‘Uh, over there!’ I say, pointing towards the sanitisation room, which looks interesting with its padlocks and humming generator. I guess it’s the kind of place you’d hide aliens, if they existed. One of the men, with a ponytail like a ferret sneaking down his collar, throws me an awkward look, then wanders towards the room as if he were on a farm tour. His friends follow close behind, disappearing into the doorway.

Alex appears from behind the cages, looking pale. ‘Where’ve you been? I’ve cleaned the same cage three times. The manager started asking me to leave when everyone started shouting about escaped chickens. The next thing I know, those weirdos run in and demand to know where the staff are hiding the bodies! I mean, what bodies?’

‘Yeah, it’s weird … no time to explain! Quick, let’s get these birds into my bag.’

He sighs and flicks open the nearest cage, but it’s not easy. You can’t tell chickens you’re rescuing them from a life of imprisonment. Good thing I’m still wearing gloves because they claw and fight. I’m wondering if Mum gets paid danger money, when footsteps echo around the cages. Gasping, I grab the nearest bird and ignore the sharp pecks, knowing I can soak my arm in Dettol later.

I push the flapping chicken into my backpack, sliding the zip into place just as one of Mum’s workmates races past. Mrs Thornton blinks at us, only pausing for a second as she puffs, ‘You kids better get out of here, right now. There’s a bunch of weird tourists running around, we’ve called the police but they’ll be miles away. You’re safer at home, off you go!’

‘Okay!’ I sprint for the door, hoping that running will disguise the fact my backpack jumps by itself. ‘We’re outta here.’

No one seems to notice us leaving. I don’t think they’ll miss one chicken and if they do, I doubt they’ll be able to prove anything. They’ll just blame the protestors.

Hey, Dad? Give Saint Jude a high-five from me.