Irena Sendler.

Yad Vashem

A PETITE POLISH woman approached the nine-foot wall of the Warsaw ghetto. The entrance was blocked with barbed wire and armed guards. The woman told the guards that she was a social worker and was there to assist the sick. That statement was true, but she was there for an additional reason, one that she dared not share with the guards. In her pocket she had the addresses of several homes. The people who lived there weren’t necessarily sick, but they all had children. She was going to get these children out if she could.

The woman was Irena Sendler, a Polish Christian who had many ties to the Jewish community. Her father had been a doctor who often cared for patients who couldn’t pay him back, including many Jews. When he died, representatives of the city’s Jewish community approached Irena’s mother and offered to pay for Irena’s education in gratitude for her father’s kindness.

Irena had grown up playing with Jewish children and had even learned to speak Yiddish, a language spoken by European Jews. One of her good friends was a Jewish woman named Ewa. They were both social workers for the Department of Social Welfare in Warsaw, providing whatever was necessary to the poorest people in the city, especially any children living in poverty.

When the Jewish ghetto was formed in Warsaw, Ewa and Irena suddenly found themselves on opposite sides of a nine-foot brick wall, a wall guarded diligently by the Germans, day and night. It wasn’t easy for Poles to get in, and it was nearly impossible for Jews to get out.

Irena and Ewa began working together to provide help for the neediest Jews in the ghetto, the children. Children were the most vulnerable to the two biggest threats associated with ghetto life: disease and hunger. The most effective way to save them was to get them out.

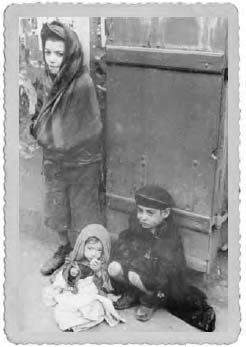

Children in the Warsaw ghetto.

Yad Vashem

The first children Irena secretly removed were those who had been orphaned and left homeless on the ghetto streets. But even the children who still had parents were at great risk for disease and undernourishment. And there was always the growing threat of deportation to camps, a dark and unknown destiny. Children, Irena knew, would be the easiest to save. The Nazi and Soviet occupation had created many orphans; the Jewish children could pretend to be Polish orphans.

Ewa had provided Irena with names and addresses of certain families. Irena carried this list in her hand as she approached the guard at the ghetto’s entrance. Once she was inside the gates, she knocked on the doors at the addresses Ewa had given her. The doors would open cautiously as Irena introduced herself and explained why she was there. Many of the parents were shocked. A complete stranger was asking them to hand over their children because she might be able to remove them from the dangers and hardships of the ghetto and might be able to place them in a convent or a private home? Some parents refused outright, some agreed quickly, while others were willing to be convinced that this was best for their children. But the one question Irena heard over and over from almost every parent was “Can you guarantee that my child will survive?” Irena was not even certain that she would make it past the guards safely. But she would do her best. That was the only promise, the only hope she could give to the desperate parents.

Irena used several routes to take the children out of the ghetto, but the one she used most often led through the courthouse building located inside the ghetto. She would take the child inside the building. Then, they would walk down a flight of stairs to the basement. One particular spot in the basement ceiling contained an opening that led to the street above, where an ambulance waited to take the child out of the ghetto and to a hiding place.

One reason many Jewish parents were hesitant to hand over their children to a Polish Christian woman was that even if Irena could actually guarantee their child’s safety, the child might be coerced into forgetting his or her Jewish identity and embrace Christianity instead. These fears were not groundless. Rescued children were each given a new Polish name to replace their Jewish one, to protect them from the Nazis. “Your name isn’t Rachel, but Roma,” Irena would say to one, and to another, “Your name isn’t Isaac, but Yacek. Repeat it 10 times, 100 times, 1,000 times.” Irena also taught them Christian prayers, so that they would appear to be Christian if tested.

But even as she was imploring children to memorize their new Christian identities so that their lives could be saved, Irena was also preserving each child’s true identity. She made up a list on small strips of tissue paper that contained each child’s false Polish name, true Jewish name, and location where he or she was currently living. She placed two identical lists into two separate bottles and buried them under an apple tree in a friend’s yard. She had to be extremely careful in hiding the lists; if the Nazis found them, they would be able to track down every single child Irena had saved.

On October 20, 1943, Irena was having a party to celebrate her name day (the date she had been baptized in the Catholic Church). She set aside the identification lists that she had been updating. Her friend, an associate in the work to hide Jewish children, stayed overnight.

Suddenly, in the early morning hours, there was a horrendous pounding at the door. It was the Gestapo!

Irena ran straight to the lists and threw them to her friend, who caught them and promptly placed them inside her bra. The Gestapo spent two destructive hours in Irena’s apartment, looking for information that would enable them to arrest other members of Zegota, the large Polish Resistance organization dedicated to helping Jews that Irena had been working with since 1942. Irena didn’t dare look at her friend, for fear the Nazis would search her as well and find the hidden lists.

When they couldn’t find anything related to Resistance work, the Nazis ordered Irena to come with them. She dressed in a hurry, forgetting to put on her shoes. The sooner they all left the apartment, the less likely the Gestapo would be to find the lists of children’s names.

The Gestapo interrogated Irena in two locations, the second time at the infamous Pawiak Prison, doing whatever they could to get her to talk. They showed her a list of informers who had betrayed her, and they advised her to do the same. They tortured her repeatedly, beating her feet and legs until they broke her bones. She refused to say anything, so the Nazis finally decided to execute her.

Just before she was to be executed, Irena was suddenly released instead. Zegota Resistance workers had bribed a Nazi official to free her. Irena actually saw posters that publicly announced her death.

THE IRENA SENDLER PROJECT

THE IRENA SENDLER PROJECT

In 1999 three female high school students from Kansas were given a year-long extracurricular project for National History Day: find information on an obscure Polish woman named Irena Sendler who was said to have rescued 2,500 Jewish children from the Warsaw ghetto. The end result was a play written and performed by these students called Life in a Jar, which, by November 2009, had more than 280 performances in the United States and Poland and brought Irena’s story to the world stage. When the girls discovered that Irena was still alive, they were able to fly to Poland and meet her in person on five separate occasions before she died in 2008. They now run the Irena Sendler Project Web site (www.irenasendler.org).

When the war was over and it was time to reunite the children with their parents, it was discovered that most of the parents had died in the Treblinka death camp. Many of these orphans were relocated to Israel, where they were able to grow up with a strong Jewish identity. Irena had directly saved, or helped to save, 2,500 of them.

Irena received the Yad Vashem Righteous Among the Nations award in 1965 and the 2003 Jan Karski Award for Valor and Courage. She was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. She died in Warsaw in 2008.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler (CBS, 2009) is a TV movie starring Anna Paquin in the title role.

Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project

www.irenasendler.org

This Web site was created and is maintained by the high school students who discovered Irena’s story and who conducted hours of personal interviews with her.

Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project by Jack Mayer (Long Trail Press, 2010) is available from the Irena Sendler Project Web site.

Life in the Warsaw Ghetto by Gail B. Stewart (Lucent Books, 1995).