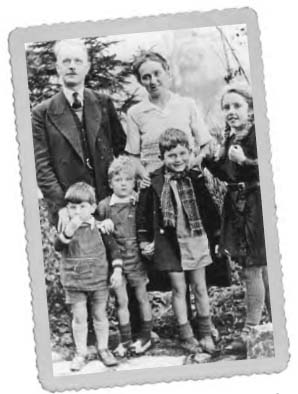

Andre and Magda Trocme with their children in the late 1930s.

Trocme family collection

MAGDA TROCMÉ, the wife of the Protestant pastor André Trocmé, lived with her family in the small French village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. She was cooking dinner one evening when she heard a knock at the door. Who could it be at that time of day? When she opened the door, she saw a woman covered with snow, shivering with fear and cold. The woman asked if she could come in. Magda guessed that the woman must be a Jew. She also knew that it was illegal to hide or help Jews.

It was the winter of 1940. Just months before, German troops had victoriously entered France, occupying the northern and western section and allowing the southern section, known as Vichy France, to govern itself under German authority. Vichy France was very anti-Semitic, and the swift laws enacted against the Jews proved that point painfully. French Vichy officials aggressively began to round up all Jews in France, beginning with Jews of other nationalities and then moving on to Jewish French citizens, placing them all in internment camps (temporary camps) before eventually transferring them permanently to concentration camps where they were sure to die.

This horrible news quickly spread, reaching all 12 villages of the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau in southern France, including the little village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. The two Protestant pastors of that village, André Trocmé and Edouard Theis, began a series of sermons, preaching from the Bible stories of the Good Samaritan and the Sermon on the Mount. They strongly encouraged their congregation to make Le Chambon-sur-Lignon a “city of refuge” (based on the biblical Israelite cities of refuge) for any Jews. The Resistance work of the village was to be civil disobedience only, distinctly nonviolent, in keeping with the pacifism (a philosophy of opposition to any type of violent action) embraced by both Trocmé and Theis.

Most of the villagers living on the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau, including those in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, were naturally empathetic to the endangered Jews. Most of them were descended from the Huguenots, the first Protestants in Catholic France who had been cruelly persecuted for their faith. Pastor Trocmé’s congregation listened to his sermons and heartily believed that they could make Le Chambon a haven for the Jews.

And so, when a freezing, frightened woman appeared at Magda Trocmé’s door, Magda’s response was quick and firm: “Well, come in!” She didn’t need her husband’s sermons to convince her to help this woman, but because she supported his work in every way, it gave her even more of a reason to help. Her own religious convictions were quite different from André’s. Her beliefs focused not so much on devotion to God as much as a dedication to assist anyone in need. She’d always had a passion for helping people, a passion that had led her to attend the New York School of Social Work as a young woman.

When André first met Magda while he was attending Union Theological Seminary in New York, he was struck not so much by her beauty or intelligence, both of which she had in abundance, but by her simple concern for others. When a group of students was leaving for an outing in Washington, D.C., André heard Magda tell one of the young men to take his sweater so he wouldn’t get sick from the cold weather.

Whether it was protecting a college friend from the cold or attending to this German Jew who was shivering and fleeing for her life, Magda wanted to help people. She sat the woman down by the fire, gave her some food, dried her wet shoes in the oven, and then went out to try to get the woman some help.

VIVARAIS-LIGNON PLATEAU

VIVARAIS-LIGNON PLATEAU

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon was not the only village on the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau to hide Jews, and André Trocmé was not the only pastor in the area who strongly encouraged his congregation to do so. There were 11 other pastors and thousands of individuals living on the plateau who were involved with Jewish rescue and who made the area one of the most successful rescue operations of Word War II. But André Trocmé was certainly a leader of the movement and the catalyst who initiated much of the rescue operation for the entire plateau.

But when she asked the town’s mayor for assistance, he strongly discouraged Magda from protecting the woman. Magda was too concerned about doing right to be worried about her own danger, and she also knew that many of the other villagers were probably hiding Jews. But she realized that by telling the unsympathetic mayor about the woman, she had just jeopardized the woman’s life. The woman must, unfortunately, leave for her own safety.

Magda returned to the parsonage, horrified to see that the woman’s shoes were now burnt. After scouring the village for another pair, she gave the woman directions to another refuge outside of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon where she was sure there was shelter. Then Magda sent her on her way.

Although she did all she could do for the woman, the destiny of that first refugee who had knocked on her doorstep haunted Magda for the rest of her life. How could she possibly know if the woman had made it to safety?

Magda quickly learned whom she could and could not trust, and slowly but surely the parsonage—and the entire village—was buzzing with refugee work. A number of refugees lived at the parsonage, some longer than others, and Magda was also part of the busy network that continually sought hiding places for the steady stream of refugees pouring into Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. She had four of her own children to care for, plus four student boarders who were attending the school that her husband and Edouard Theis had founded in 1938. She was also a full-time teacher of Italian at the school, which was providing an education for the many refugee children now in the village.

Magda was often so exhausted that she was unable to sit down and eat. Her daughter Nelly recalls that she would occasionally perforate the shell of a raw egg and suck the egg out, just to keep from fainting. But Magda’s stress was self-imposed; she willingly accepted her many duties and would have done nothing different. She explained it this way: “I never close my door, never refuse to help somebody who comes to me and asks for something. This I think is my kind of religion. When things happen, not things that I plan, but things sent by God or by chance, when people come to my door, I [feel] responsible.”

If the activities of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon were becoming well known to outside rescue organizations, they couldn’t possibly be hidden from the local Vichy police. One day a Vichy official demanded from André Trocmé the names of all the Jews he knew were hidden in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. André refused, telling him that the Jews were his brothers. He said, “We don’t know Jews, we only know men.” The official then threatened André with imprisonment.

A few months later, in the late afternoon, there was a knock on the door of Magda and André’s home, the parsonage. Visitors were far from unusual at the busy parsonage, but the two adult Jews living in the house went to hide before Magda answered the door, most likely on Magda’s orders. When she opened it, she saw two gendarmes (French local police officers) standing there. They asked her if André was at home. He was not, but she invited them to sit down and wait for his return. Since it was dinnertime, she invited the gendarmes to eat dinner with the family, as was customary in the parsonage.

How could Magda bear to be so hospitable to two men who were certainly there to take her husband to prison, perhaps to his death? Her answer is this: “We always said, ‘sit down’ when somebody came [at mealtime]. Why not say it to the gendarmes?” In this surprising gesture, Magda was embodying the Christian ideals that André had preached the day after France signed the armistice with Germany years before: “The duty of Christians is to use the weapons of the Spirit to resist … violence … without fear, but also without pride and without hatred.”

When André arrived home, the gendarmes allowed him to pack a suitcase and then led him away with Edouard Theis and Roger Darcissac, the head of the public school. Many people from the village came to bid them good-bye, singing the Protestant hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” André might have been filled with many worries as he drove off with the gendarmes that night, but he was unshakably confident of one thing: he knew that the rescue operation of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon would continue without him—that his wife and each villager would continue the work that he and Edouard had started, even if they both died in prison. The work did continue, and in the end the little village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the neighboring communities on the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau managed to rescue approximately 5,000 refugees, including approximately 3,500 Jews.

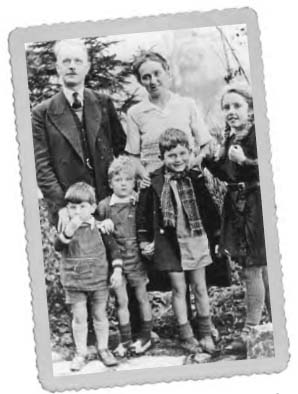

A postcard from a photograph taken during the war of the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau.

Trocmé family collection

André and Magda both survived the war. They became co-secretaries of the Mouvement International de la Réconciliation, the European branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation—a pacifist organization they had both belonged to for years—lecturing and traveling extensively for the Fellowship. Later, they moved to Geneva, Switzerland, where Magda taught high school Italian and Italian-French translations at the School of Interpreters at the University of Geneva, and where André again became a pastor.

Decades after the war, members of Yad Vashem became aware of the rescue operation in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and wanted to honor André Trocmé with their Righteous Among the Nations award. André didn’t understand why he would be singled out when so many other people, including Magda, had been responsible for the rescue operation on the plateau. “Why me?” he asked, “and why not my wife, whose behavior was much more heroic than mine?” Yad Vashem responded several years later by granting Magda the designation too, as well as many other individual villagers from the Vivarais-Lignon Plateau. Yad Vashem also recognized all who had participated in the rescuing activities on the plateau by erecting in their honor an engraved stone in Jerusalem. Former refugees placed a bronze memorial plaque on a public building near the village church in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

Angels and Donkeys: Tales for Christmas and Other Times by André Trocmé, translated by Nelly Trocmé Hewitt (Good Books, 1969). André Trocmé told these stories to the children in his and Magda’s home village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.

Hidden on the Mountain: Stories of Children Sheltered from the Nazis in Le Chambon by Karen Gray Ruelle and Deborah Durland Desaix (Holiday House, 2006).

I Will Never Be Fourteen Years Old: Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and My Second Life by Francois Lecomte, translated by Jaques P. Trocmé (Beach-Lloyd Publishers, 2009).