Gilleleje harbor, where many Danish Jews began their escape to Sweden.

The Museum of Danish Resistance

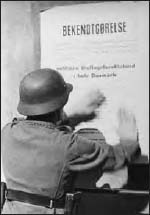

IT WAS AUGUST 1943. Twenty-year-old Ebba Lund read the words on the poster. It stated that, due to the increased acts of violence against the occupying German forces in Denmark, the Danish government was now dissolved. Germany was taking complete control of Denmark. After three-plus years, Germany had had enough of Danish rebellion.

Ebba could remember clearly the day that Denmark had been invaded. She had been woken by a heavy, humming sound, but since she had no idea what it was and it was too early to get up for school, she had gone back to sleep. Riding her bike to school hours later through the streets of Copenhagen, Ebba saw a crowd of Danes formed around a smaller group of German soldiers who were holding weapons. She stopped to see what was going on.

A young man standing next to her said, “I just can’t believe it.”

“What’s happened?” Ebba asked.

“We’ve been occupied!” he answered.

Ebba didn’t quite understand. Was Denmark at war? She kept riding until she came to the British embassy. Trucks pulled up in front of the building. German soldiers got out, entered the building, and came out with people whom they forced into the trucks. They were British diplomats, now under arrest, since Germany and Great Britain had declared war on each other months before.

The sympathetic Danes standing by began to chant, “Hurrah for the Britons!” Suddenly, a German shouted, “Anyone attempting to escape will be shot.” His grim warning temporarily silenced the encouraging chants. Then, they began again, “Hurrah for the Britons!”

The Germans didn’t want the Danes to think that the British were their friends. Part of the reason the Germans had invaded Denmark was so that Denmark might serve as a geographical buffer between Germany and Great Britain in case of a British invasion. But the Germans told the Danes the lie that they were protecting the Danes from a possible invasion of their tiny country by Great Britain.

Many Danes were content with the polite German occupation, but others were deeply offended and joined Resistance organizations. Some of these organizations were involved with explosives, weapons, and acts of sabotage and assassination. Others, like the ones Ebba Lund and her sister, Ulla, joined, published illegal underground newspapers. By 1942, two years after the invasion, there were 48 different underground papers in Denmark (and by the end of the war there were 166). Frit Danmark (Free Denmark), the paper for which Ebba Lund worked, was the most popular of all Denmark’s underground presses because of its lively writing style and its inclusion of many different political opinions, both liberal and conservative. By the end of the war, over six million copies of Frit Danmark had been published.

Frit Danmark. “Events Draw Closer to Denmark: Parliament Must Act Now.”

The Museum of Danish Resistance

The debate over the necessity for illegal groups and newspapers ended with the publication of another paper, the public one that Ebba had just read. It stated that because of the rise of sabotage activities, the Danish government had lost its ability to maintain order and was being shut down.

The Danish government had resigned the day before the edict, on August 28, rather than cooperate with the Germans any longer. The Danes were finally united and not a moment too soon; shortly afterward plans for a roundup of all Danish Jews became known. The Germans ran Denmark now, and nothing was going to stop them in their quest to destroy all of Europe’s Jews.

Nothing except the Danes. They quickly took action. Sweden had promised to accept any and all Danish Jews who could be brought there. All over Denmark, rescue plans were set in motion.

THE EDICT OF AUGUST 29, 1943

THE EDICT OF AUGUST 29, 1943

Recent events have shown that the Danish Government is no longer in a position to maintain Law and Order in the country…. I am ordering the following to take place with immediate effect:

Crowds and meetings involving more than five persons on the street or in a public place are prohibited, as are all assemblies, even in private.

Closing time is decreed to occur at sundown. From this point onwards, traffic on the streets will also cease.

All the use of the Post, Telegraph, and Telephone is prohibited until further notice.

All strikes are prohibited. Fomenting strike action which causes damage to the German Wehrmacht assists the enemy and will normally be punished by death.

Any encroachment of the above edicts will be punished according to standard German law. Any acts of violence, assembly of crowds, etc., will be ruthlessly suppressed by force of arms …

A German soldier posts the Edict of August 29, 1943.

The Museum of Danish Resistance

Ebba joined the sabotage-oriented Resistance group Holger Danske (named for a legendary Danish hero), which was planning to work its rescue operation out of Copenhagen. Members of Holger Danske planned to secure as many fishing boats as possible, raise money to pay the fishermen, then take the Jews to Sweden in these boats.

Since Ebba’s family regularly vacationed on the island of Christianso, and she knew many fishing families from that island, she was given the task of securing the boats. She contacted the son of a fisherman who knew of an eccentric Danish fisherman called “the American” (because he had once spent some time in the United States). She found him by his fishing nets outside the hut where he lived near a Copenhagen harbor. She approached him and offered to pay him well if he would take some Jews to Sweden. He agreed. Then she asked him if he knew of any other fishermen who would be willing to transport Jews. He did, and soon Ebba and her group had almost a dozen boats at their disposal.

Now they needed money. Most of the fishermen who agreed to rescue the Jews were very willing to help, but they needed money to participate in the rescue operation. If they were caught by the Germans or if anything else happened to their ship during the trip to Sweden, they would lose their livelihood. Ebba and the others working with her managed to find enough money in a matter of days. Wealthy landowners were asked for donations, and most gave generously. Ebba also helped raise money from people in Copenhagen.

They had the boats. They had the money. Now they needed the refugees. Again, word got out quickly, and safe houses were set up in Copenhagen—including Ebba Lund’s home—where the Jews could hide until they could be taken safely to the harbor.

Soon hundreds of Jews were flocking to Copenhagen and being sent to Sweden in the group of boats that Ebba had organized. Most of the other Danish rescue missions operated only under cover of darkness, but Ebba did her work by the light of day. Her reasoning was that the Germans had established a sundown curfew and she didn’t want to invite extra trouble. Plus, who would suspect an illegal rescue operation to be occurring in broad daylight?

During the rescue operations, Ebba became known as the Girl with the Red Cap, Red Cap, or Red Riding Hood because she would wear a red cap as a silent signal to the Jews who would be escorted to the port with directions to look for her. Ebba would then walk them down to the boats, pay the fishermen, and make sure the Jews got away safely. The boats used in Ebba’s operation could hide approximately 25 to 35 people at one time below the deck in the passenger cabins.

One day, after Ebba had helped a group of Jews into a boat and had already taken off her red cap, she was standing on the pier about to pay the fishermen when five Germans in grey Wehrmacht uniforms began walking toward her. If they asked to search Ebba’s bag, they would find a large amount of money there—10,000 kro-ner—which was enough to raise serious suspicions about what Ebba was doing on the pier. She had to think fast.

The fishermen looked up at the approaching Germans. Ebba quickly walked up to one of the fishermen, hooked her arm into his, and smiled at him lovingly. The fisherman took the hint and smiled right back at Ebba. The Germans stared at the loving couple for a moment, then turned and walked away.

There were many reasons why Ebba didn’t have more close calls. One reason was that members of the Holger Danske group and the Danish coast guard kept an armed patrol on the rescue operations out of the port where Ebba was working. The Germans, many of them Wehrmacht soldiers and not the Jew-hating SS, knew this and apparently didn’t want to get killed over a rescue operation. Others had been bribed to look the other way. Some of them would even tell the Danish coast guard exactly when they were going to patrol the port and when they would be gone.

But still, Ebba was taking a great personal risk in helping the Jews. One day it became graphically clear to her what fate she had been rescuing them from. A passenger who had escaped from Germany showed Ebba a photo of piles of dead bodies from a Polish concentration camp. Ebba was extremely disturbed by the images—in her wildest imagination, she could not have pictured such horror when she set out with her friends to rescue the Jews.

Ebba felt compelled to become involved in the Jewish rescue before she knew the particulars because, as she said many years later, “For me it was not a Jewish problem, it was a simple humanity problem.” The Holger Danske group helped approximately 700 to 800 Jews escape from German-occupied Denmark in just a few weeks.

After the war, Ebba studied chemical engineering and immunology (the study of how the body fights disease) and did important research regarding the polio virus. She later became the head of the Department of Virology and Immunology at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University in Copenhagen. She was heavily involved in scientific research and served on many science-related committees all her adult life. She died in 1999.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

Darkness over Denmark: The Danish Resistance and the Rescue of the Jews by Ellen Levine (Holiday House, 2000) includes the story of Ebba Lund’s rescuing activities.

“‘Girl in Red Cap’ Saved Hundreds of Jews”

San Diego Jewish Press-Heritage

www.jewishsightseeing.com/denmark/copenhagen/1994-01-14_red_cap_girl.htm

An interview with Ebba Lund dated January 14, 1994.