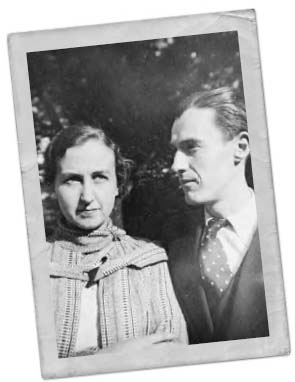

Pearl Witherington and Henri Cornioley.

Hervé Larroque

THE ALLIED INVASION of Nazi-occupied France—D-day—had finally come. Urgent orders had come from London to obstruct the roads to hinder German troops from getting to the Normandy coast, where the Allies had just landed. Pearl Witherington, an SOE agent, and the rural French maquis fighters she was working with had been very busy for two days following these orders, blocking the roads in their area with felled trees and large pieces of debris.

A young man who had just bicycled in from Paris, 120 miles to the north, was outside the gatehouse of the chateau property where Pearl and her team of maquis were living. Pearl questioned him about the condition of the roads to the north.

She was shocked by what he told her: the only obstructions he had seen were in their immediate area. None of the other networks had obeyed the order. The Germans, always trying to weed out bands of maquis, would certainly come looking for whoever had created these obstructions.

Two days later a low-flying reconnaissance plane (referred to by the maquis as the Snoop) flew over Pearl’s area. Had the pilot seen them?

Apparently so. At 5:00 A.M. on June 11, 1944, five days after D-day, a group of maquis leaders in a truck near their headquarters ran right into a group of Germans. They were able to get away, with German bullets flying after them.

About 2,000 German troops moved in, attacking both Pearl’s maquis network and a Communist one to the south. Pearl grabbed her small sack of personal items and a cocoa box in which she kept the network’s money. With bullets whizzing by her ears, she biked to where the weapons and explosives were kept. She began to assemble the guns, fill them with ammunition, and put fuses on the grenades.

A young maquisard suddenly rushed in and told Pearl to get out because the Germans were already there. Pearl dropped the weapons, took her sack of personal items and the cocoa box—which contained approximately 500,000 francs—and ran into a wheat field, where she hid for the rest of the day.

Were these the actions of a hero? Why didn’t she stay and fight?

Pearl always had good reasons for her choices, and no wonder: decision making had been forced upon her very early. Her English father, who brought his family to Paris for his work, was an alcoholic who wasted his family’s money. Because of this, and the fact that she spoke French well, certain responsibilities fell on Pearl’s young shoulders. Even at the age of 12, she often had to speak to creditors and landlords on behalf of her family.

When Pearl was 17, her father left. Pearl then went to work to support her three younger sisters and her mother, who was in poor health and could barely speak French. Pearl held various secretarial jobs and also taught English in the evenings. Eventually, she obtained a very good desk job at the British Embassy with the Air Ministry.

Then, in June 1940, the Germans invaded France. All embassy employees were boarded on a train and sent to Normandy to catch a boat to England. But at the last minute it was announced that only employees who had been brought over from England would be shipped out. No provision was made for employees who had been hired locally, like Pearl. She and her family were stranded in Normandy without money or even a place to go. Pearl went to the American embassy in Normandy and through her connections with her former embassy job, she was given some financial help to allow her and her family to get back to Paris, now occupied by the Germans. Then, a few months later, when they heard rumors that Germans were rounding up English people in Paris, Pearl guided her family through a seven-and-a-half-month exodus from France, managing all the tedious customs and embassy details herself.

When they finally arrived in England, Pearl and her sisters joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), where they worked as office staff and secretaries. But Pearl was not content with her desk job. Memories of German-occupied Paris—the swastika banners flying in the streets, the posters announcing the murders of innocent Parisians—filled her with anger. She wanted to take a more active role in fighting the Germans.

Pearl had heard that there were people, fluent in French, who were being trained in England to work with the French Resistance. She asked her superior at the WAAF about it, but he said this organization was composed of “amateurs,” and he forbade her to apply. However, when Pearl related her frustration to a friend, she discovered that this friend worked for the head of the secret operation. He contacted Pearl, and she was in.

What Pearl had joined was the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization that trained agents to work in Nazi-occupied countries. Pearl was a good candidate for the F (French)-Section, but some of her instructors thought she lacked leadership qualities, suggesting she would do well only under the guidance of a strong leader. She was assigned to work as a courier under Maurice Southgate, a man whose code name was Hector Stationer. The Stationer network was collecting intelligence (information) regarding German activities, training local French fighters—the maquis—in the use of weapons and explosives, and conducting selective acts of sabotage.

She parachuted into France on the night of September 22, 1943, after being forced back to England on two previous occasions due to bad weather. Her suitcases ended up in the bottom of a lake, and she didn’t get them back for weeks. Then, from September 1943 until May 1944, posing as a cosmetics representative, Pearl functioned as a courier for the Stationer network, delivering important messages from place to place.

The area covered by the Stationer network was very large, so Pearl spent most of her time on night trains, using a special pass that precluded her from most Gestapo searches. French railways at that time didn’t have private sleeping cars—men and women were thrown together haphazardly—so Pearl often chose to sleep in her seat, in the unheated cars. This took a toll on her health, and early in 1944 she became ill for several weeks.

Courier work was often dangerous, sometimes in surprising ways. Once Pearl was sent to collect money from a certain maquis leader, but she had been given no password with which to identify herself. She was greeted coldly. She tried to give code names of other agents. This did nothing. The leader became more hostile. Pearl sensed she was in serious danger. Finally, she mentioned the name of the farmer on whose property she had landed the night she parachuted into France.

THE MILICE

THE MILICE

The Milice Française (French militia) was established in Vichy, France, to locate and arrest French Resistance workers and Jews. Members of the Milice had a particularly brutal reputation and, in a way, posed more danger to Resistance workers than the Germans did, since as French natives they could detect small differences in French accents that the Germans could not. Members of the Milice were also expert at recruiting local informers. By the beginning of 1944, the Milice had spread from Vichy to the entire country.

Suddenly, several large men came into the room. They had been listening and were under orders to strangle Pearl if it turned out that she was an agent of the Milice, the traitorous French militia. They were now convinced that she wasn’t. She was safe, but she thought later, “If I had not managed to convince him with the last name, I don’t know how I would have got out of it…. Being killed by another Resister, that would have been the end!”

Just a month before D-day, Pearl’s leader, Maurice Southgate, along with his radio operator, was captured by the Gestapo at his residence in Montluçon. The Gestapo found the radio in the house, along with lists of the various drop fields and the network’s money. Germans surrounded Montluçon the next day. Pearl, her fiancé Henri Cornioley (who had joined the network), and some others escaped the area by small back roads before splitting up. Pearl, Henri, and a radio operator fled to the chateau, several miles to the northwest, where they established a new base of operations.

With Maurice Southgate gone, who would take over the leadership of the Stationer network? Pearl, now using the code name Pauline, was the obvious choice. She was SOE-trained, she had expertise in all the weapons and explosives, and she had communication with London.

The Stationer network was split in two. Pearl directed the northern half, which was now called Marie-Wrestler. She further divided Marie-Wrestler into four parts, each led by its own lieutenant who answered to her. They reestablished contact with London and received fresh shipments of arms. They were just beginning an escalated campaign of harassing German troops, cutting German communication lines, and causing damage to a major railroad line that ran through their area when the Germans attacked the area on June 11. Pearl escaped into the field with the box of money.

The battle lasted for 14 hours. Two small maquis groups—100 people in a different (Communist) group and 30 in Pearl’s—put up quite a fight, killing over 80 Germans. But the Germans killed over 30 of them. By nightfall, when the trucks had all left, Pearl emerged from the wheat field to find that they had no radio and no weapons, and the Marie-Wrestler group was now down to about 20 people (including—happily—her fiancé, Henri).

Pearl and her group had been trying to recruit more fighters to their ranks before the Germans attacked. When she had run into the field with the cocoa box, Pearl had this thought: with the money she had saved, she could pay each new recruit a small salary and feed them until more money could be dropped from England. By late July the Marie-Wrestler network had grown to almost 1,500 maquis and had received drops from 60 planes totaling over 150 tons of arms.

From late June 1944 to the end of August, when France was liberated, the Marie-Wrestler network staged 80 acts of sabotage on the rail line, frequently attacked German convoys on the road, and killed about 1,000 Germans. They provided information to London that enabled the Royal Air Force to attack a 60-tank train of gasoline bound for Normandy (after D-day). And at one point, a column of 18,000 Germans surrendered to the Allies as a direct result of being harassed by the maquis in Pearl’s area.

She went to France with the misgivings of her SOE instructors, and her efforts there were plagued with setbacks. Yet Pearl emerged from her difficulties to become one of the only women to lead a maquis group during the war. And in the end, it was clear-headed thinking—such as leaving the guns and grabbing the money—that enabled Pearl to succeed. The maquis of her network loved her and called her “our mother” and “our National Pauline.”

In September 1944, Pearl and Henri went to London, where Pearl concluded her service with the SOE, turned over reports of her activities, and returned all the remaining money with a detailed accounting of how the rest had been spent. (She seems to be one of the few agents to have done this.) A few weeks later, practically penniless and unemployed, Pearl and Henri were married in London. Then they returned to Paris at the end of the year to begin civilian life.

Pearl was granted numerous awards by the governments of Great Britain and France, and in her later years she was approached by many writers who wanted to help write her memoir. She always refused because she didn’t want to see her life story transformed into a dramatic fiction. But in 1994, French journalist Hervé Larroque convinced Pearl to grant him an interview that would be published. She agreed because she realized her story might encourage young people to persevere in difficult circumstances; she knew that her own hardships had prepared her for successful Resistance work. The result was the French-language memoir, Pauline.

Pearl died in February 2008.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

Translated English extracts from Pauline: The Life of an Agent of the SOE by Pearl Witherington Cornioley and Hervé Larroque (Editions par exemple, 2008; in French, though a full English translation is being prepared).

http://herve.larroque.free.fr/pauline_uk.htm.

“Pearl Witherington: SOE Officer Whose Leadership of French Resistance Fighters Was a Thorn in the Side of the Germans Before and After D-day.”

Times Online

www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/obituaries/article3432757.ece An obituary of Pearl Witherington.