WHEN HITLER’S TANKS rolled into Poland on September 1, 1939, the reaction in the United States was largely one of upholding the same isolationist policy that had made the country initially hesitant to become involved in the previous world war. The America First Committee (AFC), whose spokesman was aviation hero Charles Lindbergh, believed that getting involved with a European war would destroy, not strengthen, the American way of life.

But when the Axis powers began to conquer country after country—Germany in Europe, Italy in North Africa, Japan in the Far East—many isolationist Americans began to change their thinking: the Axis was creating a very lopsided world.

The U.S. Congress, which in the 1930s had passed many Neutrality Acts to prevent President Franklin D. Roosevelt from allowing the United States to contribute money and arms to the growing European conflict, finally relented in 1941. In March of that year Roosevelt was able to aid Great Britain in its fight against Germany by passing the Lend-Lease Act, which supplied Great Britain with billions of dollars’ worth of war equipment.

Americans became largely unified on December 7, 1941, when Japan bombed the U.S. naval base stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (part of a massive Japanese assault on American, British, Dutch, and Australian territories throughout the Pacific Ocean). Americans, especially those who lived in Hawaii and on the West Coast, became terrified that Japan would now begin a ground invasion. That terror faded when the invasion didn’t occur, but it was replaced with a fervent patriotism and desire to fight the Axis powers.

The United States declared war on Japan, and then Germany, Japan’s ally, declared war on the States. American men and women signed up for the armed services by the hundreds of thousands. For the first time in U.S. history, women had their own branches of the armed services. The first—and largest—of these divisions was the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which had approximately 140,000 women in its membership. The female branch of the navy was called Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the female coast guard branch was called SPAR (Semper Paratus, Always Ready), and the female marines were simply called the female marines; they had no special designation.

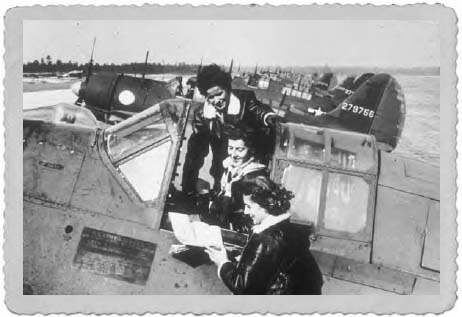

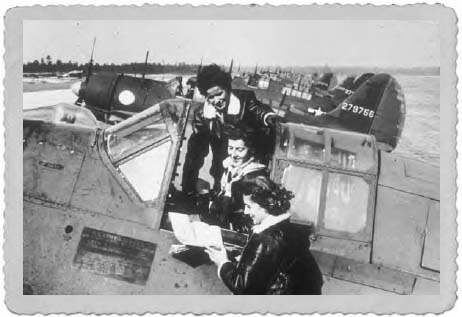

Two female pilots, Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Love, began two different pilot training programs for women that eventually merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). The WASPs’ main job was to fly newly manufactured planes to military bases within the United States, where air force men would then fly them out of the country into combat zones. WASPs also helped train antiaircraft crews by flying back and forth with a target trailing 25 feet behind the plane. Yet the WASP organization was not technically part of the armed forces—its members received no armed service benefits aside from pay, and the program was shut down in 1944, before the war ended.

Many civilian women also supported the war effort. When American men left farms and factories to join the armed services, there was a huge labor shortage. The Women’s Land Army hired thousands of women—from the cities and the country—to work U.S. farms to prevent a national famine. And manufacturing companies, given government money to produce airplanes, ships, and weapons, encouraged American women to work in factories to help the war effort. American women responded enthusiastically to the call for well-paying factory jobs, and eventually their numbers reached into the millions. These women became associated with a fictional character named Rosie the Riveter, who was the subject of a new popular song about a patriotic girl working in a munitions factory using a riveting machine out of love for her marine boyfriend.

Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs).

National Museum of the United States Air Force

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was a U.S. organization devoted mainly to espionage, created in 1942 by World War I veteran William J. Donovan at the request of President Roosevelt. Most of the 2,000 women employed by the OSS (out of a total 16,000 employees) worked far from danger. Others, such as Virginia Hall (see page 197), were dropped into enemy territory and worked as agents, gathering vital information for the U.S. government and the Allies and helping to organize Resistance workers.

On June 6, 1944, Allied forces composed mainly of American, British, and Canadian troops landed on the beaches of Normandy under the leadership of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The German forces who met the Allied forces at Normandy (determined though greatly depleted in number from their costly battle against the Soviets) were severely hindered in their rush to the Normandy coast by numerous maquis groups and other Resistance workers, some of whom were being supplied by the OSS and the British Resistance organization, the SOE.

The Allies were eventually able to push the Germans out of France. The following year, on May 7, 1945, the German armed forces formally surrendered to the Allied forces in a schoolhouse where General Eisenhower kept his headquarters. The United States would remain in the war until Japan, the country that had gotten the States involved in the war in the first place, formally surrendered to the Allies on September 2, 1945.