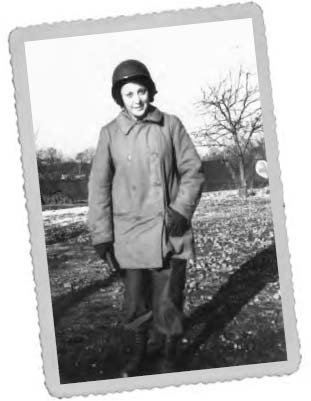

Muriel Phillips during the Battle of the Bulge, holding a blackjack in her right hand and a switchblade in her left pocket, both gifts from wounded GIs in case she was captured by the Germans.

Muriel Phillips Engelman

WHEN MURIEL PHILLIPS heard the news, on December 7, 1941, that the United States Navy had been bombed by the Empire of Japan, she was in her final year of nurse’s training at Cambridge Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The following day, all the nurses on her floor gathered around the radio in the doctor’s office to hear President Roosevelt give his “Date of Infamy” speech, which informed the American people that the United States had declared war on Japan.

DATE OF INFAMY SPEECH

DATE OF INFAMY SPEECH

President Roosevelt’s Date of Infamy Speech, broadcast on the day following the attack on Pearl Harbor, is one of the most famous speeches of the 20th century and was instrumental in stirring thousands of young Americans to enlist in the armed services during WW II. The following are excerpts from the speech:

Yesterday, Dec. 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan….

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. Very many American lives have been lost….

No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory….

With confidence in our armed forces—with the unbounding determination of our people—we will gain the inevitable triumph—so help us God.

There was no question in Muriel’s mind what she would do: right after she finished her nurse’s training, she would enlist in the armed services as an army nurse. As difficult as nursing school had been, her army training at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, was even more difficult. It included hours and hours of various drills, 15-mile hikes, climbing up and down rope ladders, classroom study of various diseases, and even crawling under live ammunition.

When Muriel finished her army training and set off for Great Britain, she and the other nurses took along many things that had been given to them during their training, including K-rations (packets of canned and dried food), special clothing, gas masks, and helmets. The helmets caused more complaint than the K-rations did. They might as well have weighed a ton for how uncomfortably heavy they were. Why did the helmets have to weigh so much? Muriel would find out soon enough.

Muriel worked in Wales for six months, caring for the everyday illnesses of some of the thousands of U.S. soldiers stationed in Great Britain. For their next assignment, she and her entire hospital unit—500 enlisted men; 50 medical, dental, and administrative officers; and 100 nurses—were going to cross the English Channel to nurse the wounded of the Normandy invasion (which had taken place several weeks earlier) and await orders for their final destination.

Muriel and the other American nurses of her hospital unit with whom she trained in Fort Devens, marching in a parade in Chester, England, 1944. Muriel is the platoon leader, in front, saluting the “brass” (superior officers).

Muriel P. Engelman

The nurses decided to sleep on the ship’s deck as the rooms below were infested with bedbugs. Muriel could hear the German planes flying overhead as she lay in the darkness; she had learned the difference between the sound of a German plane and an Allied one. But because a blackout had been ordered on the ship, all the lights had been extinguished. Muriel and the other nurses were not visible to the enemy planes as their transport ship crossed silently through the dark waters of the English Channel.

A trip across the Channel usually took only two or three hours, but all the debris in the water—remnants of airplanes and ships—had slowed the trip down substantially so that it took them three days. Finally, the coast of Normandy came into view. Muriel packed the heavy equipment onto her back and descended the rope ladder with the others in the hospital unit onto the flat-bottomed LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel), which took them closer to the beach. When they were about 100 feet from land, they got off the LCVP and waded ashore, where they were loaded onto trucks.

As their trucks approached the nearest village, Muriel and the others became silent. The sights—and smells—of war were everywhere. Homes and farms lay in ruins. Piles of rubble lay where buildings had once stood. The smell of death and decay hung in the air.

Because their trucks got lost in the dark, the nurses spent their first night in Normandy sleeping under the stars in a cow pasture. It was very smelly, but they knew if the cows were still alive, the field must be free of German mines. Although they worked for some time in Normandy, the ultimate destination of Muriel’s hospital unit was an apple orchard just outside the city of Liége, Belgium. Their mission was to set up and operate a tent hospital, which would be used to nurse the many soldiers who were being wounded in the Allied push against the Nazis.

TENT HOSPITALS

TENT HOSPITALS

During World War II, any type of hospital, whether evacuation, field, or general, could be set up in tents. Muriel’s hospital was a general hospital and contained almost everything a regular hospital would. Because tent hospitals were outdoors, on ground level, it was much easier to transport patients in and out than it would have been in a storied building. Each individual tent in Muriel’s hospital held 30 beds and was heated by a pot-bellied stove. Liége was a coal-mining center, so it was easy to keep the stoves fueled. Muriel’s hospital was spread out over several acres of an apple orchard and contained a total of 1,000 beds.

For the first few weeks, most of the tent hospital floors were dirt, which quickly turned into mud during the constant rain. During these first weeks, Muriel and the other nurses cared for their patients without the benefit of electricity or running water, working by the light of flashlights and kerosene-fueled lanterns.

After Muriel and her unit had been near Liége for about a month, the Germans began sending buzz bombs (the V-1 bomb, or the robot bomb) all over the area. A single buzz bomb contained nearly 2,000 pounds of explosives and made a “putt-putt” sound before plunging to the earth at a 45-degree angle with a loud, horrible, whining whistle. It would destroy everything within a few hundred feet, and the explosion could be felt miles away.

Liége contained a huge network of railroad lines that fanned out in many directions and connected with many different countries. The Germans knew that if they could destroy the center of these rail lines in Liége, it would greatly hinder the Allies’ ability to transport soldiers and equipment. And so the buzz bombs bombarded Liége, sometimes three at once from three different directions, coming every 15 minutes for two solid months. Some of the bombs landed directly on sections of the large tent hospital where Muriel and her hospital unit were trying to nurse their patients.

Muriel wrote about this two-month bombing spree in a letter to her cousin, dated November 26, 1944:

Never in my year overseas have I put in such a hectic life as I have the past few weeks and I’m afraid if the buzz bombs continue annoying us the way they have, I won’t have to worry about any postwar plans. We’ve been lucky so far, having had some narrow squeaks, but it can’t last. It’s the most awful feeling in the world when you hear the motor of the bomb stop almost above you and then wait a few seconds for the explosion. I’d rather have it all at once and get it over with, but then, Hitler never consulted me. Incidentally, keep this mum, won’t you, as I wouldn’t want my mother or Ruth to worry though frankly, I’m scared silly and for the first time in my life I’ve lost my appetite.

I’m on night duty in our tent hospital which is in a sea of mud, and with the continual rain for the past 2½ weeks, it will never dry out. The work has been hard and the hours long but I really feel satisfied now because we’re doing the stuff we came overseas for, and they really need us. Our quarters are in the heart of a city, some miles from here, so we have to commute each night—leaving there at 5:00 P.M. and getting back at 10 the next morning—and we’re supposed to sleep. Sleep, however, is out of the question when buildings all around us are being bombed and each time they get it, the force practically knocks us out of bed.

Muriel had used her helmet mainly for washing her clothes and bathing herself, but now she finally understood why it was so heavy: it provided solid head protection when the bombs came too close. She often wished she could squeeze her entire body inside its protective weight.

Despite the difficulty of the work, nothing gave Muriel more satisfaction than tending to the needs of wounded GIs. They were the most uncomplaining patients she had ever nursed. They knew their nurses were busy, so they hesitated in asking for help and always told the nurses to take care of the other patient first. Muriel felt very proud to be helping such brave servicemen.

In December 1944, six months after the Normandy invasion, the buzz bombs were still falling all over Liége, but now something even worse was on the horizon. German troops launched a sudden surprise attack that managed to push U.S. troops backward, making a bulge in the troop line, in what was called the Ardennes Offensive, more commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The tent hospital became more crowded than ever with wounded GIs, and the Germans were coming closer and closer. Muriel had more to worry about than most of the other nurses. Her dog tag—the metal identification tag that every serviceman or -woman was required to wear at all times—had an H on it, for Hebrew. Muriel was Jewish, and she understood what the Nazis would do to her if they were able to capture her.

On Christmas Eve, the Germans were only 10 miles from Liége. The sickest patients were evacuated to hospitals in France or England, away from the fighting. The wounded GIs who remained in the tent hospital were concerned for the safety of their nurses and often urged the nurses to take their places in the evacuation vehicles. None of the nurses did so, of course. Muriel received two “presents” from her protective patients that week. One was a blackjack, a type of weapon made out of rubber hosing and lead sinkers, and the other was a switchblade. Muriel had no idea if she would be able to follow the instructions that accompanied her gifts if approached by a German (the blackjack was to be slapped across his eyes and the switchblade plunged into his abdomen), but she was grateful for her patients’ concern.

GI

GI

The initials GI stand for government issue, the words that were stamped on almost everything military personnel were given. Soon the initials began to stand for the servicemen, or soldiers, themselves.

That night, the fog that had enveloped Belgium for over a week suddenly cleared. Muriel heard the sound of a German plane flying overhead. She went outside to look. The pilot was flying back and forth over the tent hospital, dropping flares to light his targets. Then he began flying very low and strafing (shooting at) the tent hospital while dropping antipersonnel bombs as well. All of Muriel’s patients that night were able to walk on their own, so everyone took shelter under the beds. Many patients and hospital personnel died that night before an Allied antiaircraft gun finally shot down the German plane.

After Christmas week, Muriel could see and hear waves of U.S. planes overhead by day and British planes by night as they flew off toward the Ardennes Forest to combat the advancing German army. Muriel thought that she had never seen such a thrilling and beautiful sight.

Although the Germans broke through the Allied line in several places, the Allies eventually won the Battle of the Bulge toward the end of January 1945. A little over three months later, Germany surrendered, and the war in Europe was over.

After the war, Muriel—along with everyone in her hospital unit—was awarded a European Theatre ribbon and medal. They also each received three battle stars, one for each campaign, or battle, that they had been involved in. One of these stars was awarded for their work in nursing wounded soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge.

In 2008, Muriel published the memoirs of her eight-decade life, including 11 chapters on her war experiences. She called the book Mission Accomplished: Stop the Clock. She often gives talks about her war experiences.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

And if I Should Perish: Frontline U.S. Army Nurses in World War II by Evelyn Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee (Anchor, 2004).

11 Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge by Stanley Weintraub (NAL Trade, 2007).

Mission Accomplished: Stop the Clock by Muriel P. Engelman, World War II Army Nurse, retired RN (iUniverse, Inc., 2008).