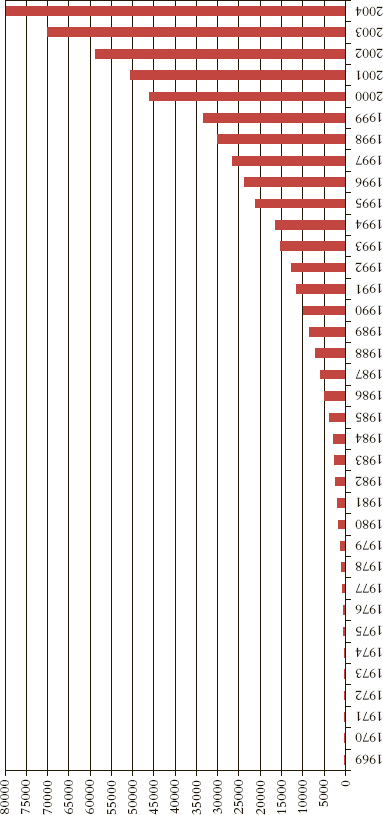

Figure 12.1 AIG’s Net Income (1969 to 2004) (in millions)

AIG’s founding corporate board in 1967 included luminaries who made AIG into the largest insurance company in the world: insurance industry Hall-of-Famer Jimmy Manton; the old Asia hand Buck Freeman; the quintessential MOP John Roberts; the life insurance builder Ernie Stempel; and Starr’s loyal long-time confidant, K. K. Tse. In the ensuing decades, AIG enlisted some of its most distinguished corporate officers to serve on its board of directors. Those traditional officer-directors not only knew the company and the insurance business well but were world travelers who understood the demands of building a global financial services company.

The early board appreciated the appeal of nominating some directors from outside AIG for election by shareholders. Such nonemployee directors offered fresh perspectives, opened doors to business opportunities and made decisions when employee directors faced conflicts of interest. Among early outside directors was Greenberg’s first mentor, Mil Smith (1969–1984), who brought years of valuable experience and connections as an innovative industry leader with a broad worldview.1 Outside directors who served during the 1970s through the 1980s included former cabinet officials,2 international business executives,3 foreign service officers,4 central bankers5 and financial accountants.6 In general, these outside directors served as senior advisors, without tending to second-guess managerial judgments, particularly concerning arcane insurance industry matters beyond their expertise. Outside director Dean P. Phypers (1979–1999), chief financial officer of IBM, noted that this was the standard corporate governance model of the period, at AIG and elsewhere: a collegial body operating in an atmosphere of trust and informality.7

That model began to change in the 1970s—just as American Home launched its thriving directors and officers (D&O) insurance business. Routinely ever since, in response to national scandals involving corporate misconduct, Congress passed new legislation and the New York Stock Exchange—where AIG listed its shares in 1984—adopted rules that increasingly required corporations to add outside directors to the board. The authorities also first suggested and later required increasing numbers of committees whose membership was limited to outside directors. These changes were aimed at checking management shirking and enhancing corporate performance, though empirical research never provided much support that such reforms achieved such objectives.8 Legislators, regulators, and judges seemed to believe that, at the very least, outside directors would be able to exercise independent judgment. On that basis, as a “reform” to respond to crisis, elevating the number and power of outside directors helped forge political consensus. It did not matter whether directors had knowledge of a company’s operations or industry or any other expertise.

Letting political expediency dictate business practice is always dangerous and such universal regulation necessarily overlooked variation among companies. Concerning AIG, its roots as a private company, its long-standing entrepreneurial culture and engagement in the complex field of international insurance all pointed in favor of an inside board. Nevertheless, throughout this period of increased enthusiasm for outside directors on corporate boards, AIG successfully recruited capable people who added the value of their business judgment and experience and put the interests of AIG and shareholder prosperity first.

From 1985 until his death in 1990, AIG’s board boasted William French Smith, President Reagan’s personal lawyer, a partner with the law firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and former attorney general of the United States.9 A similarly esteemed outside director from 1991 until his death in 2003 was Barber B. Conable Jr., a pragmatic professor and congressman for two decades, before becoming a reforming pioneer as president of the World Bank.10 Yet another impressive independent director was Lloyd Bentsen (1994–1998), former U.S. senator from Texas, secretary of the treasury, and Democratic vice-presidential candidate. In 1955, Bentsen had founded the Consolidated American Life Insurance Company, which he ran until 1967, and later created a billion-dollar private investment firm that formed global infrastructure funds, especially in Latin America.11 His obituary in the New York Times observed that none of his colleagues in government could “recall a single instance in which he let his emotions get the better of him.”12

With outside directors like these—experienced, informed professionals who understood what they could add and appreciated the limits of their expertise—the practice of nominating such directors for election by shareholders made sense. Despite such esteemed appointments, some corporate activists—from institutional investors, such as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association–College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF), to coalitions such as the National Association of Corporate Directors—campaigned in the 1990s and early 2000s to overthrow the AIG board’s traditional approach to director selection. These campaigns were part of a national mission to amplify “shareholder voice” in American boardrooms and targeted large corporations. Some campaigns sought to promote diversity or affirmative action, but many urged greater numbers of outside directors, trumpeting their unique ability to render independent judgments rather than having any particular knowledge or expertise.13

One activist AIG shareholder, the Presbyterian Church, submitted proposals to adopt a formal board nominating committee staffed by outside directors. It said this would support a public policy of “equal employment opportunity and workforce diversity.”14 It complained that AIG’s practice of having the full board screen and nominate directors “clouded” the process and that an independent nominating committee would “uncloud” it—apparently echoing the period’s perception, among corporate governance gurus, of the purity of outside director “independence.”

AIG’s board opposed such proposals, citing the company’s decades-long record of profitability and tremendous growth in shareholder value. Consider the accompanying tables (Figures 12.1 and 12.2) depicting AIG’s net income and shareholders’ equity from 1969 to 2004.15

Figure 12.1 AIG’s Net Income (1969 to 2004) (in millions)

Figure 12.2 AIG’s Stockholders’ Equity (1969 to 2004) (in millions)

AIG’s board had from 15 to 20 serve as directors in any given year, each a full-fledged member entitled to participate without distinction between inside or outside status. Every director could make, discuss and vote on nominations. Management’s views on director identity and qualifications were invaluable, and AIG’s management directors were substantial AIG shareholders, aligning their interests with those of its legions of loyal shareholders, which included a large number of public pension funds. In a 2001 response to such proposals, the board noted that management directors owned or controlled, principally through SICO, 500 million AIG shares then worth $48 billion (of 2.3 billion total shares outstanding).16 Excluding them from the nomination process seemed absurd.

An individual shareholder presented a more subtle “shareholder democracy” argument supporting an independent nominating committee.17 He posited that, regardless of the board’s strong arguments about AIG’s track record, selection criteria and management-director ownership, shareholders should get to exercise their vote, rather than have the board preempt that privilege. AIG’s board responded that its job was to propose nominees to shareholders based on qualifications. It was not its job to “create a political environment” in which “nominees compete for the available directorships.” If people knew they had to campaign for the position, such an approach would reduce the pool of candidates. Besides, such campaigns can distract the board from its duties and cause divisions within it.

Another activist targeting AIG was an AFL-CIO affiliate, which proposed that AIG adopt a policy requiring that a majority of directors be outsiders. The argument contended that a corporate board is a “mechanism for monitoring management.”18 Labor union officials argued that meeting a strict test of independence enables directors to “challenge management decisions and evaluate corporate performance from a completely free and objective perspective.” It cited a lone study arguing that “corporations with active and independent boards enjoy superior performance”19—though many more studies show that director independence has no effect on corporate performance.20 The objective in such campaigns was not always to improve performance as much as to strengthen outside directors while weakening management and the CEO.

The overwhelming majority of AIG shareholders voted such proposals down, with only about one-fourth of shares voted in favor of them, low even by the standards of activists who considered such losing votes a victory. AIG’s board and most of its shareholders favored governance that had delivered sustained long-term growth in shareholder value. AIG had thus earned a reputation as a “core stock holding” for many portfolios, including those of the proverbial “widows and orphans.”21 AIG shareholders preferred to have the existing directors and management identify directors for nomination and shareholder election, with enviable results.

By the early 2000s, AIG’s board included a combination of inside and outside directors who respected each other and worked well together with Greenberg. Besides Greenberg, management directors were the long-serving Edward Matthews, who had been with the company from its inception and advised it on many transactions through his retirement in 2003,22 and Howard Smith, the second chief accounting officer in AIG’s history, having succeeded Peter Dalia in 1984. Other insiders included two younger executives being groomed as successors to Greenberg: Martin J. Sullivan and Donald P. Kanak.23

The board included 10 outside directors—a majority of the 18-person group as stock exchange rules by then required. The most senior was M. Bernard Aidinoff, the partner in the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell who had represented AIG in its initial public offering, the establishment of Starr International Company (SICO), and many other transactions.24 Some held impressive internationalist credentials, such as Carla Hills, former U.S. trade representative with whom AIG had worked on trade in services.25 Ambassador Hills is a trained lawyer and Washington-based international consultant, with expertise that includes risk management. From that same walk of life, and also a trained lawyer, was William S. Cohen, former U.S. senator from Maine and secretary of defense, a committed internationalist with sound business judgment and expertise in Asia.26

Others brought a diverse range of viewpoints. Ellen V. Futter, elected in 1999, ran the American Museum of Natural History and had been president of Barnard College. Futter, yet another lawyer, had chaired the Federal Reserve Bank of New York during a term when Greenberg was vice chair before succeeding her as chair. Elected in 2001 was the internationalist Richard C. Holbrooke, a senior U.S. diplomat who served in the Carter and Clinton administrations, including as ambassador to Germany, where AIG was eager to expand. Greenberg believed that Holbrooke’s knowledge of Germany would prove useful to AIG. Also elected in 2001 was Frank G. Zarb, who had significant experience in international matters and the financial sector, having led both Smith Barney and the Nasdaq stock market—although Greenberg would later discover that he had not distinguished himself in those roles. Greenberg had several years earlier assisted Zarb in becoming president of an insurance brokerage firm, Alexander & Alexander, in which AIG had taken a minority interest.

Throughout any given year, board members coordinated informally as issues arose and met at scheduled meetings four times annually. An executive committee was formed to make official decisions between regular meetings. It kept the large company nimble in a dynamic world where opportunities come and go quickly. If senior officials in Malaysia or Shanghai needed a prompt response on an extraordinary matter, AIG could provide it. Besides Greenberg, the 2004 executive committee members consisted of outside directors Aidinoff; Hills; Frank Hoenemeyer, a retired vice chairman of Prudential Insurance Company; and Zarb.

The audit committee, which AIG established in the early 1970s, oversaw internal controls and accounting processes to assure accountability and accuracy. To maintain management discipline, Greenberg and Matthews held weekly AIG-wide management meetings with 15 senior officers. Each reported on respective areas of operations, keeping everyone accountable and current on what was happening. AIG also held monthly meetings with all the company’s divisional and subsidiary presidents, 30 in all, to conduct the same exercise on a different scale. Members of AIG’s board were invited to join these monthly meetings and most did so often.

A corporate board’s primary task is appointing senior officers. In keeping with longstanding corporate policy that Greenberg had established at the founding of AIG, no officers had employment contracts. The board likewise endorsed the long-standing corporate policy Greenberg started that individual compensation be modest, certainly by prevailing American corporate standards. Officers earned a salary—never more than $1 million annually for anyone—and pension benefits along with stock options for performance. The steadily rising AIG share value increased the worth of SICO’s holding substantially, and SICO paid AIG managers additional compensation under the program that the “band of brothers” had begun in the 1970s. The upshot was that virtually all executive compensation at AIG was performance based, and there was little need for a board compensation committee.

AIG’s senior officers maintained a comprehensive worldwide program to enable them to identify, promote and reward the most promising AIG employees across all businesses in every country. The system dated to the late 1980s, when one afternoon Greenberg summoned to his office the head of human resources, Axel Freudmann.27

“How many people do you know at AIG?” Greenberg asked.

“I’m not sure, maybe between 500 and 1,000?”

“Exactly. That’s a problem. We don’t know enough people. We need to know more of them and to know them better.”

Freudmann established a program that involved a global search and communication protocol to identify outstanding employees in all fields, such as those who excelled at earning an underwriting profit. The human resources staff coordinated with profit center managers across the company to compare notes on employees, consult other managers with whom employees had worked for verification, and bring results to the attention of senior officers. Overcoming the corporation’s vast scale, senior managers got to know the employees and were able to reward them for stellar performance.

Another distinctive feature of AIG’s corporate governance: the board did not believe it was their prerogative to use corporate assets to make charitable donations. At most corporations, the CEO and board make discretionary allocations of the corporation’s assets to charities of their choosing, at a cost to shareholders, who may not support the chosen charities. That was not the practice at AIG, where the board believed that if shareholders wished to allocate their wealth to charitable causes, they should be able to do so and not have the board or CEO usurp that right.

Many AIG directors endowed private foundations dedicated to causes they valued. Starr had begun that practice, endowing a foundation of modest size that was concentrated in AIG stock. The Starr Foundation would grow over three decades after his death to a value of several billion dollars. Other directors, including Freeman, Greenberg, Manton, and Stempel, followed suit by establishing private foundations to make charitable gifts, which aggregated to billions of dollars.28 For his philanthropy, particularly toward the Tate Britain Museum, Manton was knighted by the Queen of England.29

Despite impressive people, policies and performance at AIG, its board did not pass muster with the corporate governance gurus of the day and their national campaign for “shareholder democracy.” A 2000 report published in a trade magazine suggested as much, along with how misguided this campaign was. It listed what it called corporate America’s “five worst boards” and “five best boards.”30 The report stressed that it was not interested in a company’s financial performance, such as growth or profitability, but only in a dozen board attributes that then defined “good governance,” such as size, ratio of insiders to outsiders, women, minorities, and committee processes.

This approach is akin to a ship captain stressing the arrangement of deck chairs while ignoring leaks that could sink it. Using this approach, after noting that AIG “enjoyed enviable profitability and growth,” these “experts” listed AIG as having the “third worst board.” The “third best board,” under this approach, was that of Enron Corporation, which the next year was revealed to be a multibillion-dollar fraudulent cypher, with scarcely any assets, income, or substance.

In response to such debacles as Enron, in 2002, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. It adopted a one-size-fits-all regime of governance and auditing—including yet more power for outside directors.31 The New York Stock Exchange marched in lockstep with an additional set of homogenous requirements. The new regime’s added roles for outside directors led AIG’s board to have a “Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee,” which Aidinoff chaired and on which Futter, Hills, and Zarb served. The committee met often and quickly produced newly required governance guidelines, committee charters and ethics codes, and stricter conceptions of “independence.” The latter had the effect of stripping Futter’s “independent” status because the Starr Foundation had made substantial donations to the American Museum of Natural History that she ran, though the foundation would have supported the museum whether Futter or someone else headed it, as it had since 1973 when it made its first gift to the museum.32

A related novel requirement was an “executive session” of the board, a separate meeting to occur around regular board meetings but solely for outside directors. No management directors were permitted, under the theory that they wield too much power in the boardroom, resulting in the “structural bias” of the outside directors, compromising their capacity for “independent judgment.” Another fashion begun in corporate America during this period was the “lead director,” chosen from among the outside directors. At AIG, this job would go to Zarb.33

These changes and devices—enacting into law what activists had sought for a decade and AIG shareholders had rejected—upset the unity that AIG’s single board historically demonstrated. It effectively incubated a group of outside directors with newfound inspiration to challenge insiders. Some of AIG’s outside directors became more assertive, many beginning to ask questions on matters beyond their competence. Some questions struck Greenberg as naïve, uninformed, or worse, and he would say so. They might call for a tutorial on the ABCs of insurance, international trade, or corporate structure that was an inappropriate use of board time. The traditional mutually supportive and respectful relationship among board members frayed.

The era of Enron and Sarbanes-Oxley stoked such media and regulatory hyperbole about corporate malfeasance that law enforcement authorities became emboldened. President George W. Bush in 2002 formed the President’s Corporate Fraud Task Force within the Department of Justice to intensify this area of law enforcement.34 Eager to police corporations and ferret out offenders, officials added pressure on outside directors, as well as independent auditors. These new government priorities motivated corporate officials to surrender employees in exchange for prosecutorial promises of leniency toward them or the corporation. The government’s rationale was famously outlined in a series of Justice Department memos about “getting tough” on corporate malfeasance, a 2003 version of which stressed “vigorous enforcement” of law against “corporate wrongdoers.”35 It contained at least one provision—restricting employer reimbursement of employee legal defense costs—that a federal court later declared to be unconstitutional overreaching by the government.36

Enforcement intensity, combined with shifting boardroom power from management directors to nonemployee directors, made it difficult to sustain AIG’s traditional employee-centric culture. Respecting that culture, Greenberg had zero tolerance for employees he knew to have violated any law or withheld information from him about pending investigations. In an incident well known among AIG insiders, Greenberg learned that a senior executive had improperly interfered with an investigation by French authorities that jeopardized AIG’s license and had not informed Greenberg. Greenberg summoned the executive to his office at 70 Pine and, with Manton present, asked the executive to explain. The executive lied about the existence of the investigation and its merits, so Greenberg excoriated and summarily fired the man, apparently ending his career. On the flip side, if an AIG employee was unjustly prosecuted, AIG mounted a vigorous defense.

One example came to a head in 2003 after the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had been hunting companies that falsified their financial statements by abusing sophisticated insurance products. The target was Brightpoint, Inc., a small provider of services to the telecommunications industry. The SEC said Brightpoint had used an AIG insurance policy to disguise $12 million in business losses. After cracking down on Brightpoint and three of its executives, the SEC went after AIG. Matters involving such relatively small amounts in a subsidiary of a much larger company were not usually the basis for an SEC fraud prosecution of the parent company. But given the period’s regulatory environment, the SEC aggressively pursued this case, and some of AIG’s outside directors were inclined to capitulate.

During the proceedings, disputes arose between the SEC and AIG about whether certain documents had been deliberately or innocently withheld. AIG’s outside counsel, Sullivan & Cromwell, acknowledged full responsibility for whatever objections the SEC had to the document production but the episode intensified the SEC’s charges and caused some AIG board members to push AIG’s management to settle. As a result, in September 2003, AIG agreed to pay a $10 million fine and provide SEC-appointed monitors to wander through the records of all its subsidiaries to look for other negligent action.37 Greenberg was not happy with this result. The crevice between management and some outside board directors was widening.

The gap grew in a second case that began in September 2004 after the SEC raised questions about a transaction between AIG’s Financial Products division (FP) and PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. To help PNC manage the volatility of some of its assets, FP arranged a deal in which PNC agreed to transfer nonperforming assets to an entity that FP created and controlled. Gains or losses on the assets would belong to FP, so PNC could remove them from its balance sheet. In exchange, FP charged PNC a fee. PNC transferred $762 million of such assets, removed them from its balance sheet, and paid FP fees of $40 million. FP vetted this concept with accountants, lawyers, and some AIG directors, and concluded that it was valid.

The SEC disagreed. To remove the assets from PNC’s balance sheet, accounting rules required AIG to stake a minimum amount of capital in the deal. It did stake that minimum, the SEC acknowledged. But, it said, the fees FP received should count as a reduction in that amount. Under that approach, AIG’s investment fell below the minimum. AIG and its advisers had been in many conversations over the years with SEC officials about complex deals like this and had never heard of this purported requirement. AIG’s outside counsel advised that it had a strong case but, again, several outside directors were more inclined to settle. AIG paid $126 million and agreed to various corporate governance reforms, including appointing another monitor, this time to oversee FP’s products to assure they could not be used by other parties to massage accounting results.38

Greenberg found this resolution disagreeable, though his objection was not whether the transaction was in fact correctly executed and accounted for by PNC. Nor was the issue what responsibility AIG should have for assuring that its products are not misused—matters about which people differ vigorously, as many Supreme Court opinions addressing the scope of “aiding and abetting” liability attest.39 The question was a matter of corporate governance: how a board should evaluate and respond to governmental assertions of corporate and employee misconduct. The gradual capitulation of several outside directors was an important and regrettable sign that members of AIG’s board were prepared to defer to government authorities. They might have presumptively believed the authorities, regarded mounting a defense as too costly, or simply disagreed with management and wanted to make that point. The rights and protections of employees were correspondingly diminished as outside directors at many American companies increasingly surrendered them in the name of cooperating with prosecutors.40

In this new environment, outside directors at companies across the United States began to further strengthen their hand and protect themselves by retaining their own lawyers to represent them. Outside directors had not historically hired their own lawyers, but Sarbanes-Oxley authorized audit committees to do so.41 A specialty legal practice emerged: representing outside directors, especially advising them on disagreements with chief executives.42 Experts on corporate governance and legal ethics saw this development as perilous, as it would cleave boards into factions, inject lawyers deeply into corporate deliberations and compromise the independence of directors. It was clear that at some point directors would be forced to choose between acting in the best interests of the corporation and acting to protect themselves.43 So it was difficult to stem the flow of lawyers into the boardroom

In late 2004, AIG’s outside directors, led by Zarb, opted for this form of empowerment and self-protection. They considered two prospective lawyers. Republicans among AIG’s outside directors suggested Richard Thornburgh, former Republican Pennsylvania governor and U.S. attorney general during the administration of George H. W. Bush. But Thornburgh’s firm, K&L Gates, had a conflict of interest that, under canons of legal ethics, prevented him from accepting the assignment. Democrats on the outside board supported Richard I. Beattie, chairman of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, who had served in the Carter and Clinton administrations and represented one of the directors, Holbrooke, during Senate hearings on his nomination to be United Nations ambassador. The outside directors chose Beattie, and Zarb charged him with strengthening the outside directors’ hand in succession planning.44

Succession is a challenging planning process for the board and CEO of any corporation, particularly one in which the leader has invested his entire career and identity. Nevertheless, knowing it was in the best interests of the company, Greenberg wrestled with succession in the early 2000s. AIG’s board had focused on Kanak and Sullivan. As of late 2004, an understanding was reached that one of them would become CEO for a trial period beginning in June 2005, while Greenberg remained chairman. Greenberg planned to vacate the executive floor at 70 Pine while staying involved as needed.

Throughout his tenure, Greenberg adhered to the presumption of innocence for AIG employees, preferring to defend them vigorously, and expected the board to do so, too. He believed that firm defenses would have been mounted in cases such as Brightpoint and PNC by boards from earlier AIG eras, certainly the board comprised of inside directors—Freeman, Manton, Roberts, and Stempel—stalwarts who had all retired by 1997 (Manton in 1988) as well as the valiant outside directors of the earlier era, such as Lloyd Bentsen, Barber Conable, Dean Phypers, and William French Smith. Greenberg was growing impatient with the new universal regime in corporate America where outside directors came to rule over territory they did not always understand. He knew his corporate world had changed and believed it was not for the better. But the worst was yet to come.

Notes

1. Another was John I. Howell (1969–1995), retired chairman of the executive committee at J. Henry Schroder Bank & Trust Company, whose global financial perspective added considerable value to AIG’s corporate board.

2. Henry Kearns (1974–1984), head of the Export-Import Bank in the Nixon administration and assistant secretary of commerce for international affairs in the Eisenhower administration. See “Henry Kearns Is Dead; Headed Export Bank,” New York Times (June 1, 1985).

3. Pierre Gousseland (1977–1993), the international mining company executive who ran AMAX Inc.

4. Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II (1972–1988) was a particularly distinguished member of AIG’s board drawn from outside the company’s executive ranks. A prominent Washington-based consultant on international affairs and nephew of General MacArthur, the ambassador served with distinction in many U.S. foreign-service posts from 1935 to 1972, including as ambassador to Austria, Belgium, Iran, and Japan.

5. Scott E. Pardee, a senior vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in charge of foreign exchange operations.

6. Michael N. Chetkovich, a prominent accountant and former managing partner of Deloitte Haskins & Sells, one of the “big eight” international accounting firms of the period. See “Michael N. Chetkovich, 81, Top Accountant” New York Times (April 30, 1998).

7. Cunningham telephone interview with Dean P. Phypers, November 28, 2011.

8. See Lawrence A. Cunningham, “Rediscovering Board Expertise: Legal Implications of the Empirical Literature,” Cincinnati Law Review 77 (2008): 465–499.

9. Richard D. Lyons, “William French Smith Dies at 73; Reagan’s First Attorney General,” New York Times (October 30, 1990).

10. Conable had also served on AIG’s board during 1985–1986, the period between his service in Congress and becoming president of the World Bank. See “Conable Elected to AIG Board,” Contact (October/November 1991): 8; see also Wolfgang Saxon, “Barber B. Conable, 81, Congressman and Bank Chief, Dies,” New York Times (December 2, 2003).

11. David E. Rosenbaum, “Lloyd Bentsen Dies at 85; Senator Ran with Dukakis,” New York Times (May 24, 2006).

12. Ibid.

13. See Joseph B. Treaster, “Some A.I.G. Shareholders to Press for More Independent Board,” New York Times (May 15, 2000); Joseph B. Treaster, “A.I.G. Head Will Consider Altering Board,” New York Times (May 18, 2000).

14. AIG Proxy Statement (March 23, 2000), 18–20.

15. Cunningham e-mail from Howard I. Smith, July 19, 2012; “A Short History of AIG: 1919 to the Present” (March 2001), 23. The figures include the effects of the restatement of 2005 discussed in Chapter 14. Thanks to Sara Westfall, George Washington University, for creating the images from the raw data.

16. AIG proxy statement (2001), 8.

17. AIG proxy statement (March 23, 2000), 23–24.

18. Ibid., 22–23.

19. Citing Ira Millstein and Paul MacAvoy, “The Active Board of Directors and Improved Performance of the Large Publicly-Traded Corporation,” Yale School of Management Working Paper No. 49 (1997).

20. A sampling of studies, conducted after the proxy statement in question, include Sanjai Bhagat and Bernard Black, “The Uncertain Relationship between Board Composition and Firm Performance,” Business Lawyer 54 (1999): 921; Sanjai Bhagat and Bernard Black, “The Non-Correlation between Board Independence and Long-Term Firm Performance,” Journal of Corporation Law 27 (2002): 231; Benjamin E. Hermalin and Michael S. Weisbach, “Boards of Directors as an Endogenously Determined Institution: A Survey of the Economic Literature,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review (April 2003): 7.

21. See Roddy Boyd, Fatal Risk (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 45.

22. Matthews retired as an AIG officer at the end of 2002 and as an AIG director at the 2003 annual meeting.

23. The business press, some shareholders, and many directors, including Greenberg, began mulling a succession plan for the helm of AIG. See, for example, Joseph B. Treaster, “Still Secretive, A.I.G.’s Chief Promises Hints on a Successor,” New York Times (April 25, 2002); Joseph B. Treaster, “A.I.G. Makes Plans for Post-Greenberg Era,” New York Times (May 2, 2002); Joseph B. Treaster, “Market Place; When A.I.G.’s Longtime Chief Mentions a Successor, Wall Street Talks, and Keeps Talking,” New York Times (January 29, 2003); Joseph B. Treaster, “Top-Level Reordering at A.I.G. May Set Up Succession,” New York Times (December 5, 2003).

24. Other veteran outside directors were Marshall Cohen, former executive at Molson Companies Ltd., the Canadian beer company; Martin S. Feldstein, the Harvard professor, former economic adviser to President Reagan and president and chief executive officer of the National Bureau for Economic Research; and Frank J. Hoenemeyer, a retired vice chairman of Prudential Insurance Co. More recent appointees included Pei-yuan Chia, former vice chairman of Citicorp.

25. Hills was an AIG director from 1992 to 2006.

26. William Cohen was an AIG director from 2004 to 2006.

27. Cunningham telephone interview with Axel Freudmann, April 10, 2012.

28. Some activities of the Starr Foundation are noted in Chapter 16.

29. See E.A.G. Manton, “Knighted for ‘Charitable Services,’” Contact (October/November 1994); see also Manton, Contact (November 1969): 5–6; Nicholas Serote, “Sir Edwin Manton: Businessman and Art Benefactor Who Donated Millions to the Tate Gallery,” The Guardian (Oct. 16, 2005).

30. Robert W. Lear, “Boards on Trial,” Chief Executive (October 31, 2000).

31. See Donald C. Langevoort, “The Human Nature of Corporate Boards: Law, Norms and the Unintended Consequences of Independence and Accountability,” Georgetown Law Journal 89 (2001): 797; Jill E. Fisch, “Taking Boards Seriously,” Cardozo Law Review 19 (1997): 265.

32. The committee did not declare nonindependent several other directors who had relationships with other beneficiaries of the Starr Foundation, including Feldstein, Holbrooke, and Zarb.

33. Zarb’s designation as lead director was formalized at an AIG board meeting of April 21, 2005, though his role was widely recognized to precede that formal designation.

34. Executive Order 13271, 67 Federal Register 46091 (2002), available at www.justice.gov/archive/dag/cftf/. President Obama replaced this with a Financial Fraud Enforcement Task Force. Executive Order 13519, 74 Federal Register 60123 (2009), available at www.sec.gov/news/press/2009/2009-249-exec-order.pdf.

35. The memos were written by successive deputy attorneys general of the United States. See Memorandum from Eric Holder, Deputy Attorney General, U.S. Dept. of Justice, to Heads of Department Components and United States Attorneys, Bringing Criminal Charges Against Corporations (June 16, 1999); Memorandum from Larry D. Thompson, Deputy Attorney General, U.S. Dept. of Justice, to Heads of Department Components and United States Attorneys, Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations (January 20, 2003), www.justice.gov/dag/cftf/corporate_guidelines.htm; Memorandum from Paul J. McNulty, Deputy Attorney General, U.S. Dept. of Justice, to Heads of Department Components and United States Attorneys, Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations (December 12, 2006), www.usdoj.gov.dag/speeches/2--6/mcnulty_memo.pdf; Memorandum from Mark Filip, Deputy Attorney General, U.S. Dept. of Justice, to Heads of Department Components and United States Attorneys Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations (August 28, 2008), www.usdoj.gov.dag/readingroom/dag/dag-memo-08282008.pdf.

36. United States v. Stein, 541 F.3d 130 (2nd Cir. 2008).

37. See Securities and Exchange Commission v. American International Group, Litigation Release No. 18,340 (Sept. 11, 2003).

38. Securities and Exchange Commission v. American International Group, Litigation Release No. 18,985 (November 30, 2004); Deferred Prosecution Agreement between the U.S. Department of Justice and AIG-FP (November 30, 2004), available at http://lib.law.virginia.edu/Garrett/prosecution_agreements/pdf/AIG-FP_PAGIC.pdf.

39. See Central Bank of Denver v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, 511 U.S. 164 (1994); Stoneridge Investment Partners, LLC v. Scientific-Atlanta, Inc., 552 U.S. 148 (2008). In 2007, Joseph Cassano, then heading FP, reportedly acknowledged at an investors’ conference that FP had made mistakes in creating the PNC deal, which he regretted. See Brady Dennis & Robert O’Harrow, Jr., “A Crack in the System,” Washington Post (December 30, 2008).

40. See Lisa Kern Griffin, “Compelled Cooperation and the New Corporate Criminal Procedure,” New York University Law Review 82 (2007): 311.

41. Proposals to equip outside directors with power to retain independent advisors remained rare even after being ordained in 1994 by the American Law Institute. ALI, Principles of Corporate Governance § 3.04 (1994); see also James D. Cox, “Managing and Monitoring Conflicts of Interest: Empowering the Outside Directors with Independent Counsel,” Villanova Law Review 48 (2003): 1077 (making a “modest” proposal that outside directors asked to approve interested transactions of other directors retain their own lawyer).

42. Among the earliest and most prominent examples of outside lawyers exerting power in the boardroom to oust a chief executive occurred when Ira Millstein, of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, played that role in 1992’s dismissal of General Motors CEO Robert Stempel. See John A. Byrne, “The Guru of Good Governance,” BusinessWeek (April 28, 1997): 100; Alison Leigh Cowan, “The High-Energy Board Room,” New York Times (October 28, 1992).

43. See, for example, Report of the American Bar Association Task Force on Corporate Responsibility (March 31, 2003), 24, n. 54; E. Norman Veasey, “Separate and Continuing Counsel for Independent Directors: An Idea Whose Time Has Not Come as a General Practice,” Business Lawyer 59 (2004): 1413; see also Geoffrey C. Hazard Jr. and Edward B. Rock, “A New Player in the Boardroom: The Emergence of the Independent Directors’ Counsel,” Business Lawyer 59 (2004): 1389 (offering tepid acceptance of the concept).

44. Beattie’s biography on the Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP web site says he “specializes in counseling boards of directors and non-management directors on governance issues, investigations and litigation involving corporate officers and other crisis situations.” www.stblaw.com/bios/RBeattie.htm (accessed February 28, 2012).