Armand Baltazar, Digital, 2009.

“We don’t green light ideas, we green light directors who have a passion for an idea. It has nothing to do with whether it’s an original or a sequel. What matters is that they have an idea they fall in love with. This is something we can make.”

— ED CATMULL, president and co-founder

The prints for Cars had barely been struck in May 2006 when John Lasseter began to devise the idea for what would become his fifth feature film as director. Traveling around the world for the Cars publicity blitz, he had “vehicles as characters” on the brain: “I’m really into racing,” says Lasseter. “Formula racing, rally, touring car, twenty-four-hour endurance racing—there are so many different kinds, and each one is so different from NASCAR. So this idea of an international race began percolating in my head, a race where Lightning McQueen would compete, and where we would get to see our characters in other countries.”

Co-director Brad Lewis saw the potential immediately: “From America’s standpoint, after Cars, Lightning McQueen’s the best race car in the world. So the question was, ‘Is he really?’”

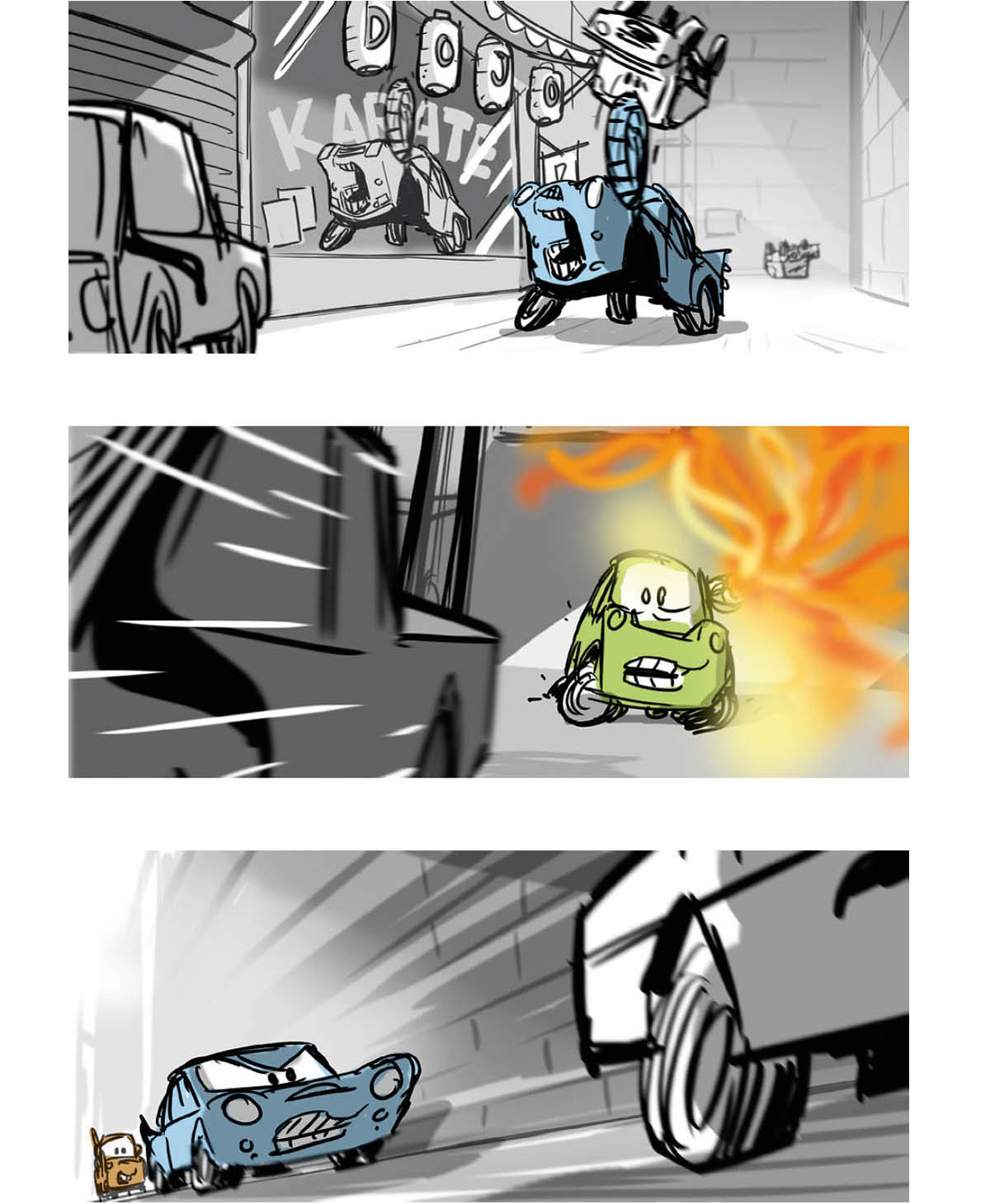

“As we started developing this idea,” Lasseter continues, “I thought about having the story become like an Alfred Hitchcock film, like The Man Who Knew Too Much or North by Northwest, where the innocent gets caught up in this spy world.” The impetus for this idea—adding a spy-thriller element to the movie—originated even earlier in a discarded scene from the first film in which Sally and McQueen go on a date to a drive-in movie theater. Rob Gibbs (story artist on Cars) and the late Joe Ranft (head of story and co-director on Cars) created the “movie within a movie”: a spy film with an ultracool car named Finn McMissile who dispatches bad-guy “Taxis of Death” with high-tech gadgetry and copious amounts of aplomb. “We just had fun designing this spy character,” Lasseter says, “and we named him Finn McMissile, because, well, he’s got missiles hidden all over him!”

Having found himself on the story-room floor in the first film, Finn McMissile was given a central role in Cars 2—this time not as an intertextual piece of background on a drive-in movie screen, but as a major character living and breathing in the Cars world.

Changing genres for a follow-up might be unusual in Hollywood, where sequel development seems to consist solely of repeating a formula over and over. At Pixar, though, genre shifting is the norm in the sequels they have tackled to date. Although tonally similar, Toy Story was a buddy film, Toy Story 2 a rescue film, and Toy Story 3 a prison break film. Cars was a mix of coming-of-age drama and slice-of-life comedy. It celebrated the values of community through the prism of small-town life off Route 66. Cars 2, although very comedic at its heart, is a fast-paced spy thriller.

Pixar’s drive for originality, its desire not to repeat itself, would seem to be the primary factor in such widely divergent sequels. But there’s also a more fundamental reason: “The most important thing in our movies is to find the underlying emotion,” Lasseter says. “It’s something you have to plan from the beginning. It’s not something you can add later. That emotion comes from the growth of the main character. And deciding how that growth happens often determines what the genre of the film will be.”

So who would provide the emotion and growth for Cars 2? To truly complete the “Hitchcockian innocent” formula, a true innocent was needed.

Lasseter, still on his creatively fertile Cars publicity tour, couldn’t help but take in the experience as a fish out of water, a self-professed “bumpkin” in glamorous cities around the world. He started to feel a little bit like Mater, the rusty old tow truck who became the unlikely best friend to superstar race car Lightning McQueen in the first film. “I started looking at each country I was in, and I found myself giggling and laughing about how Mater would react to being in places that were so different from Radiator Springs.”

Lasseter took in the confusing signage of the Tokyo overpasses, the intimidating ten-lane-wide roundabouts of Paris, the roads in Italy where it was explained to him that the traffic signals were mere suggestions (“something you might want to do”). In each situation, he just couldn’t stop asking himself the same question over and over. It was a question that would become a mantra for the Cars 2 creative team: “What Would Mater Do?”

Storyboard, Nick Sung, Enrico Casarosa, Digital, 2009.

“I think Mater resonates with people because he just is who he is; there’s no pretense to him. He wears his rust with pride.”

— JAY WARD, Cars franchise guardian

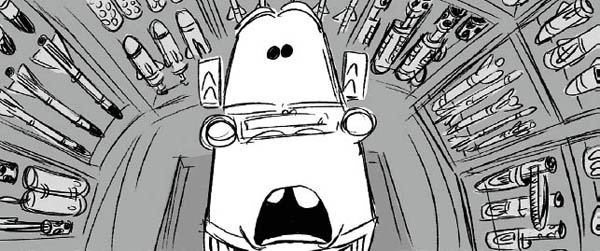

For Mater the tow truck to be a true unwitting Hitchcock hero like Roger Thornhill, Dr. Benjamin McKenna, or John Jones (North by Northwest, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Foreign Correspondent, respectively) his importance to the story could not simply end with a piece of “mistaken identity” plotting. Like Hitchcock’s protagonists, Mater is an idiosyncratic character who, though easily dismissed as an “everyman,” in fact brings a specialized skill set to bear in the film. He is savantlike in his knowledge of all things towing, salvage, and auto repair. Mater is mistaken for an American secret agent and finds himself thrust into a world of high- octane spies. Yet it’s his understanding of obscure British engines and car parts that ends up saving the day. Put simply, without Mater, the bad guys would have gotten away with it. He’s not an everyman, an idiot, or even a wise, Feste-like Shakespearean fool. He’s a simple country tow truck, nothing more, and this makes him twice the hero all the other cars with high-tech gadgets and hyperanalytic minds will ever be.

“The first film was definitely a car’s world,” says Bob Pauley, production designer on Cars (2006), “though you saw a blimp and an airplane or two. In Cars 2 you’re seeing a lot more of the other elements of that world. There are boats, and more planes, and cranes.”

This process starts with the “car-ification” of each location. “One of the ideas we developed in the original Cars was that, in the same way we see humans and human faces in rock formations and clouds and things like that, cars see cars and car parts in their natural surroundings,” says Lasseter. Production designer Harley Jessup took this idea one step further for the sets for Cars 2, designing buildings that use car parts—grilles, lights, and other car elements—in their architecture. “That made it so special,” Lasseter says. “You see all these icons that we’re familiar with, but they’re fresh and different because they’re from a car’s point of view.” Art manager Becky Neiman agrees: “It’s exciting to see all of these iconic landmarks ‘car-ified,’ like the Tokyo Tower or Arc de Triomphe made up of different car parts. All of these monuments, upon closer look—you’re like, wow, that window is a car grille, or the top of the Eiffel Tower is a spark plug.”

The hard work of the Cars creative team, which clearly defined the rules of the Cars world, allowed the Cars 2 crew to focus on expanding the world’s scope, something they felt was necessary. And this went beyond simply dropping into new countries.

Environments art director Nat McLaughlin says, “Early on we’ll ask what we can build to make sure we have the essential bits of dressing that provide the character of these countries: classic London phone booths, those light poles that you see in Tokyo all over the place—just the seasoning that you see in those countries that will provide the flavor of the production design of these sets.”

Harley Jessup and the Cars 2 art department started by listing the iconic aspects of each new location. “One of our major goals has been to caricature the design and spirit of each of those countries [Japan, France, Italy, and England],” says Jessup. “And by caricaturing, I think of it as celebrating. Our approach is to show those locations in the most beautiful way we can. So we’re building a design structure based on the most significant features of each location.” In this regard, the Cars 2 team found another corollary to the Master of Suspense. Alfred Hitchcock’s approach to building narrative was not limited to his characters. In choosing locations for Secret Agent: “I [Hitchcock] said to myself, ‘What do they have in Switzerland?’ They have milk chocolate, the Alps, village dances, and lakes . . . [so] we used lakes for drownings, the Alps to have characters fall into crevasses, and a chocolate factory for the chase. All of these national ingredients were woven into the picture.”

Armand Baltazar, Digital, 2009.

Grant Alexander, Pencil, 2009.

Bill Zahn, Digital paint over character render, 2009.

Armand Baltazar, Pencil/Digital, 2009.

Model Packet, John Nevarez, Digital, 2009.

For Jessup, though, he hopes the design strategy can, at its simplest, evoke a feeling—to “show each culture in a way that is appealing, and unforgettable.”

The overall look of the movie has evolved from the original, along with the story. The analogy, used by Brad Lewis and others on the crew is “NASCAR is to Cars as Formula racing is to Cars 2.” Formula racing, along with the spy world, has added a dimension of glamour not common along the dusty roads of Carburetor County. It’s a look that flows cleanly out of the story. “We’re taking a genre leap to this international spy conspiracy movie set in Europe,” says Sharon Calahan, director of photography-lighting. “So I think that we want to represent that genre leap visually as well.”

This idea—the symbiosis of form and content—is something that the art department aspires to every day. “The visual structure of the film grows out of the story structure,” says Jessup, “and in the spy film genre each of the locations has to be exotically different from each other. When you combine that idea with a whole world designed for and by cars you get a really exciting mix of settings and characters.”

Model Packet, Nat McLaughlin, Pencil/Digital, 2010.

On September 24, 2008, it was announced that Cars 2 would be released a full year ahead of schedule, jolting the production with a dose of much-needed reality. As with all Pixar films, the Cars 2 team members were focusing much of their energy on getting the story “right.” Many major issues had yet to be resolved, including landing what Pixar considers to be the key ingredient of every great film: its heart. “That’s always one of the challenges in creating a new story with a sequel,” says Lasseter. “Where can you mine the heart again? You can’t have Lightning McQueen unlearn everything he learned in the first film.”

The pace of the production picked up dramatically. But, though it became the first Pixar film to be completed in a three-year production schedule, on twelve-week screening turnarounds, the quality of work was not diminished. “Everyone’s still designing to a high level of detail,” says Brad Lewis. “Instead of getting push-back from our technical directors, all we’re hearing is . . . ‘we can do it.’” Producer Denise Ream: “Far and away, Cars 2 has more locations and environments than any other Pixar film to date. We’ve got seasoned veterans in all twelve departments and everyone’s standards are very high.” Harley Jessup concurs: “The strength of our creative and technical teams is inspiring. Nobody’s overwhelmed by the scope of the movie. The people I’m working with are at the top of their game and this, along with the new technology, is making it possible to do things that have never been done before.”

For example, the climactic car chase through London essentially required the construction of a complete city. While the sets team built Tokyo and Porta Corsa from scratch, London required over fifty miles of city streets lined with complex period architecture. Starting from an accurate road map of London, the sets team built a detailed kit of modular building parts based on Georgian, Queen Anne, Victorian, and Edwardian architectural styles. These building sets were combined in an infinite variety of sizes and shapes, growing up out of the London city blocks. With the addition of certain custom featured buildings and set dressings, the result was an astonishingly detailed, “car-ified” version of London that blended seamlessly with the earlier work done on Tokyo and Porto Corsa.

“With every Pixar film,” says Brad Lewis, “there’s an attempt to do something that hasn’t technically been done before. With Cars 2 the most noticeable thing is the massive scope of the production. Scope and scale.” Jessup agrees: “For an interior set, cars work best in a huge space. It helps that the cities we’re showing were built on a grand scale. We’ve further enlarged landmarks like Big Ben (actually ‘Big Bentley’) and Buckingham Palace in London, the Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe in Paris, along with the Rainbow Bridge and the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.”

Storyboards, Scott Morse, Digital, 2010.

“The daunting part about this movie was that we essentially had to design for five movies: four countries, plus the spy and race worlds. On top of that, we’re a film of ‘one-offs’—almost every set is only used once. So we had to be extremely clever about how to build and populate our environments.”

—DENISE REAM, producer

Storyboard, Bill Presing, Digital, 2010.

Storyboard, Josh Cooley, Digital, 2010.

In much the same way that a movie’s story can help form the visual style, the production’s speed became a clear correlative to the style of the movie itself, something that was felt strongly in every department. The first film (the theme of which was about slowing down and enjoying life) purposely used a shooting style more akin to a Western or a small-town movie.

According to director of photography-camera Jeremy Lasky, Cars 2 “moves quickly through different sets and locations. It’s more of a travelogue style, where you get glimpses of things in one location or one country, and then you’re off.” Or, as character supervisor Bob Moyer describes, each task on Cars 2 is approached with the desire to be “better, faster, awesomer.”

“We’re going to four different countries in the film, so there are four completely different worlds to research, design, and then ‘car-ify!’ And still, the artists’ attention to detail was always there—every detail, down to the lugnut in the center of the ‘car-ified’ flowers.”

—BECKY NEIMAN, art manager

And what of the film’s heart? Ultimately, the friendship between Mater and McQueen that was created in Cars is put to the test in Cars 2. “Once we started exploring the idea of a flaw in their friendship, an imbalance, the door seemed to finally open up for us,” says head of story Nate Stanton. “McQueen and Mater are best friends, of course, but how would their friendship do when they left their comfort zone of Radiator Springs?” Mater’s behavior, which is fine in Radiator Springs, becomes embarrassing and uncomfortable for McQueen when exported internationally. After Mater’s seemingly cavalier actions cause McQueen to lose the first race, the two friends have a fight in which the imbalance in their relationship is exposed. Over the course of the movie, both Mater and McQueen realize in their own way what is broken, and what they both need to do to fix it. “Everything else in the story hopefully services this fractured, then fixed, friendship,” says Stanton.

Lighting Study, Sharon Calahan, Digital paint over set render, 2010.