CHAPTER II

ANCIENT TOOLS

A paper that was recently read before a scientific association in England, gives interesting particulars about tools used by the artisans who worked on the ancient buildings of Egypt, and other moribund civilizations. The subject proved specially valuable in showing how skilled artisans performed their work 4,000 years ago. The great structures whose ruins are scattered all over North Africa and Asia Minor, demonstrate that great artisan and engineering skill must have been exercised in their construction, but when parties interested in mechanical manipulations tried to find out something about the ancient methods of doing work, they were always answered by vague platitudes about lost arts and stupendous mechanical powers which had passed into oblivion. A veil of mystery has always been found a convenient covering for a subject that was not understood. The average literary traveler who helped to make us the tons of books that have been written about Oriental ruins, had not the penetration or the trained skill to reason from the character and marks on work what kind of a tool was employed in fashioning it.

A trained mechanic, Flanders Petrie, happened round Egypt lately, and his common-sense observations and deductions have elucidated many of the mysteries that hung round the tools and methods of ancient workmen. From a careful collection of half finished articles with the tool marks fresh upon them—and in that dry climate there seems to be no decay in a period of four thousand years—he proves very conclusively that the hard diorite, basalt and granite, were cut with jewel-pointed tools used in the form of straight and circular saws, solid and tubular drills and graving tools, while the softer stones were picked and brought to true planes by face-plates.

That circular saws were used the proof is quite conclusive, for the recurring cut circular marks are as distinctly seen on these imperishable stones as are the saw marks from a newly cut pine plank. This proof of the existence of ancient circular saws is curious, for that form of saw is popularly believed to be of quite modern invention. That another device, supposed to be of recent origin, was in common use among Pharaoh’s workmen is proved by the same authority. We have met several mechanics who asserted that they made the first face-plate that was ever used in a machine shop, and we have read of several other persons who made the same claims, all within this century. Now this practical antiquary has gone to Egypt and reported that he found the ochre marks on stones made by face-plates that were used by these old-time workmen to bring the surfaces true.

As steel was not in use in those days the cutting points for tools must have been made of diamond or other hard amorphous stone set in a metallic base. The varied forms of specimens of work done, show that the principal cutting tools used were long straight saws, circular disc saws, solid drills, tubular drills, hand grainers and lathe cutters, all of these being made on the principle of jewel points, while metallic picks, hammers and chisels were applied where suitable. Many of the tools must have possessed intense rigidity and durability, for fragments of work were shown where the cutting was done very rapidly, one tool sinking into hard granite one-tenth inch at each revolution. A curiosity in the manner of constructing tubular drills might be worthy of the attention of modern makers of mining machinery.

The Egyptians not only set cutting jewels round the edge of the drill tube, as in modern crown drills, but they set them in the sides of the tube, both inside and outside. By this means the hole was continually reamed larger by the tool, and the cone turned down smaller as the cutting proceeded, giving the means of withdrawing the tool more readily.

As indications on the work prove that great pressure must have been required to keep the tools cutting the deep grooves they made at every sweep, the inference is that tools which could stand the hard service they were subjected to, must have been marvelously well made.

_______________

AN AFRICAN FORGE.

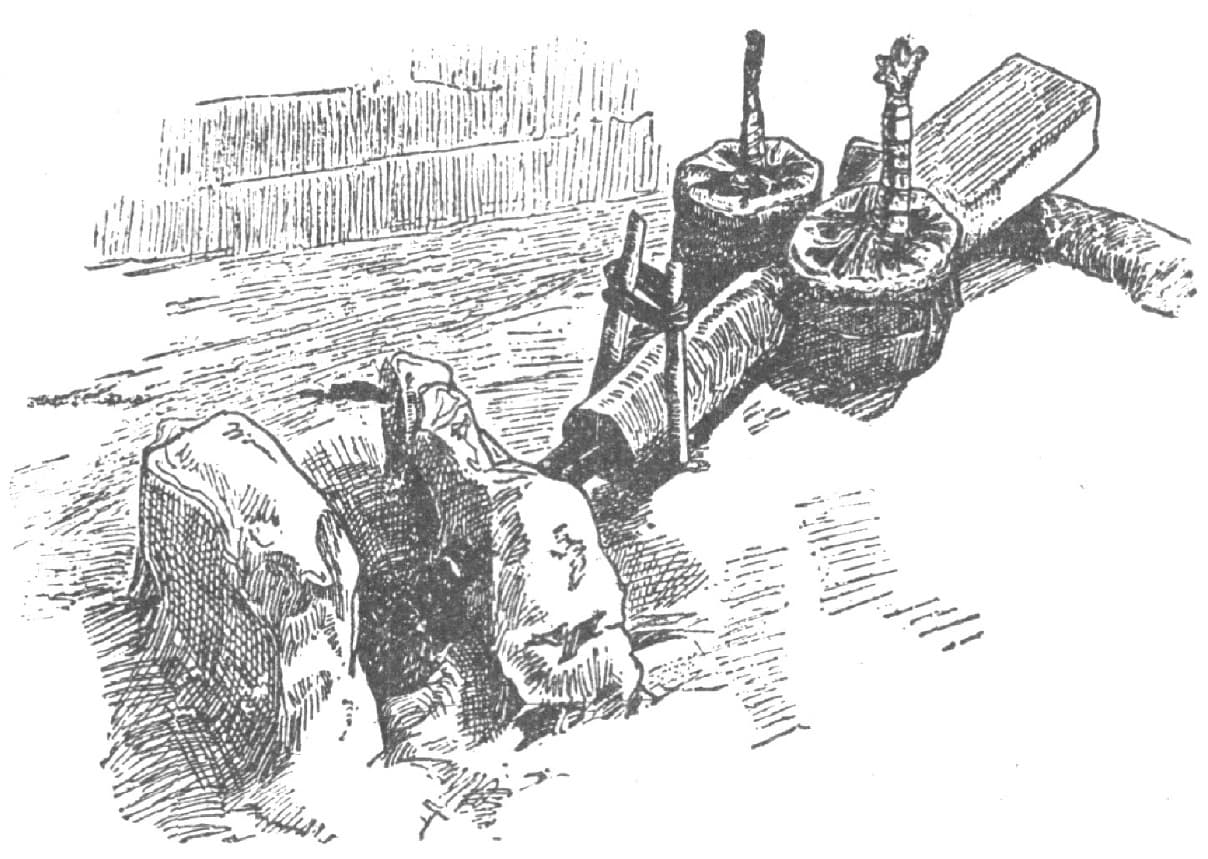

In describing his African journey up the Cameroons River from Bell Town to Budiman, Mr. H. H. Johnston refers to a small smithy, visited at the latter town, in which he came across a curious-looking forge. Many varieties of African forges had been noted by him, but this differed markedly from any he had seen. Ordinarily, he says, the bellows are made of leather—usually a goat’s skin, but in this case they are ingeniously manufactured from the broad, pliable leaves of the banana. A man sits astride on the sloping, wooden block behind the bellows, and works up and down their upright handles, thus driving a current of air through the hollow cone of wood and the double barreled iron pipes (fitted with a stone muzzle) into the furnace, which is a glowing mass of charcoal, between two huge slabs of stone. Fig. 10 is an illustration of this remarkable specimen of the African smith’s ingenuity.

FIG. 10—AN AFRICAN FORGE

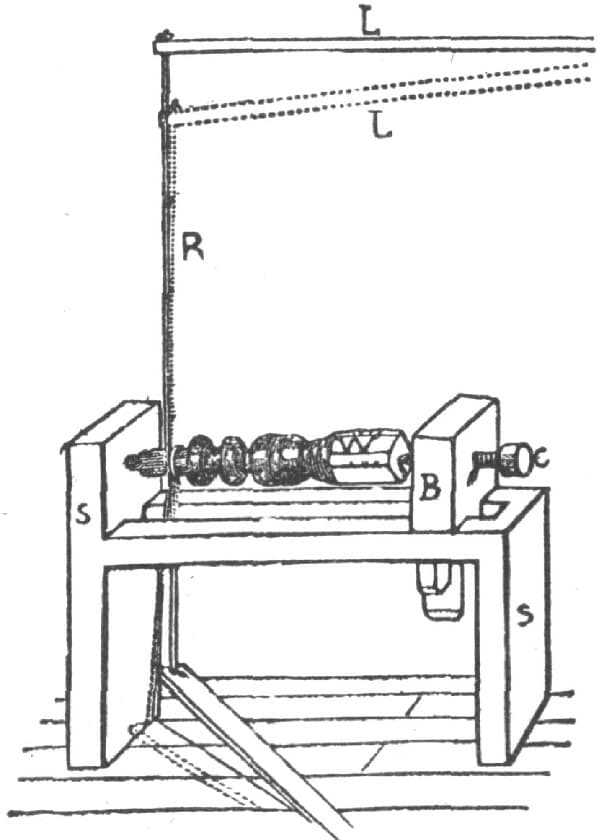

FIG. 11—A PRIMITIVE LATHE

ANCIENT AND MODERN WORK AND WORKMEN.

Forging is a subject of interest to all smiths. Excellent work was made in the olden days, when stamps, dies and trip hammers were unknown.

FIG. 12—A LATHE NOW IN ACTUAL USE IN ASIA

I saw some examples of ancient forging in the exhibition of 1851, made in 1700, that were simply beautiful, both in design and execution. They were a pair of gates in the scroll and running vein class of design. The leaves were beautifully marked and not a weld was to be seen. Now I am not one of those who think we cannot produce such work nowadays, for I feel sure we can if we could spare the time and stand the cost, but undoubtedly blacksmithing as an art has not advanced in modern times, and in this respect the blacksmiths are in good company, as was shown in the ancient Japanese bronze vases (in the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia), which brought such marvelous prices. Some of the turned works of the last century were simply elegant, and in this connection I send you two sketches of ancient lathes. Figure 11 is that from which the lathe took its name. A simple wood frame, S and S, carried a tail stock, B, and center screw, C, carrying the work, W. The motion was obtained from a lathe L (from which the word lathe comes), R is a cord attached to L, wound once around the work and attached to the treadle, T. Depressing T caused the lathe L to descend to L while the work rotated forward. On releasing the pressure on T the lathe rotates the work backward so that cutting occurs on the downward motion of T only.

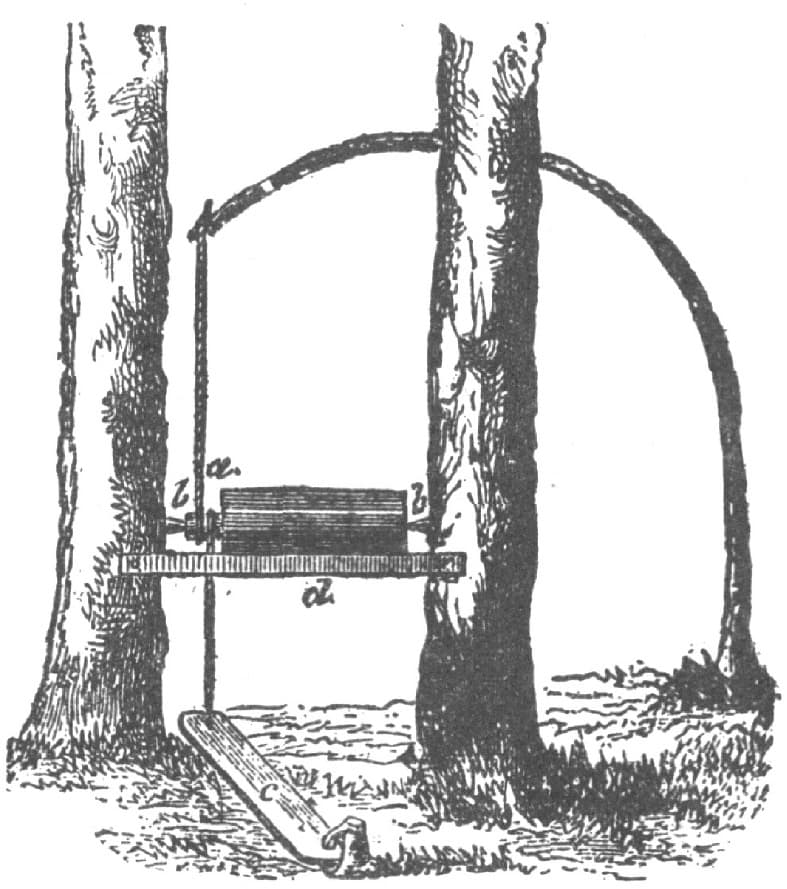

A very ancient device you may think. But what do you think of Fig. 12, a lathe actually in use today in Asia, and work from which was exhibited at the Vienna exhibition. Of this lathe, London Engineering said:

“Among the exhibits were wood glasses, bottles, vases, etc., made by the Hercules, the remnants of an old Asiatic nation which had settled at the time of the general migration of nations in the remotest parts of Galicia, in the dense forests of the Carpathian Mountains. Their lathe (Fig. 12) has been employed by them from time immemorial.”

We must certainly give them credit for producing any work at all on such a lathe; but are they not a little thick-headed to use such a lathe when they can get, down East, lathes for almost nothing; and if they know enough of the outside barbarian world to exhibit at an exhibition, they surely must have heard of the Yankee lathe.—By F. F.