For centuries coal was rarely Britain’s fuel of choice.

There were some places where people chose to burn coal from early on. In Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire, where the highest-quality ‘stone coal’, or anthracite, is found, it was in regular use when the traveller and chronicler John Leland visited in the 1540s. To his surprise, people were burning coal ‘though there be plenty wood’. Sixty years later, the Welsh lawyer and antiquarian George Owen, in his Description of Pembrokeshire, described the local coal as ‘very good’. Unlike other types of coal, he claimed, it ‘made a ready fire’ that was ‘voyde of smoake’ and produced ‘greater heate than light’. He also noted how it ‘burneth apart and clyngeth not together’ rather than smothering the fire in ash as some coals did.

In addition to its ease in burning, the coal in this corner of Wales was incredibly convenient to source. Sometimes also known as ‘peacock coal’, it had an almost oily, darkly iridescent surface and was often found in easy-to-access surface outcroppings. Gathering it was less onerous than chopping down trees for firewood. It ‘doth not require man’s labour to cleve wood and feede the fiere continually’, wrote Owen. Better yet, it was sufficiently clean-burning that ‘fyne camericke or lawne’ cloth could be dried in front of it ‘without any staine or blemish’. It was even considered as suitable ‘to rost and boyle meate’. Here – and for centuries, here alone – coal was considered to be the superior fuel, with few of the drawbacks people everywhere else associated with it.

Leland’s bewilderment was more typical of the experience most people across Britain had with coal than was Owen’s gushing endorsement. From Northumberland to Kent, most English coal did not make ‘a ready fire’ that was ‘voyde of smoake’. Quite the opposite. The coal in the rest of Wales was equally poor. Owen himself wrote that other Welsh coal was ‘noysome for smoake and loathsome for the smell’. He moaned how ‘ring coal’ from the more easterly areas of Wales ‘melteth and runneth as waxe and growth into one clodde’. The same was said of the coal then being used in Scotland.

Three hundred years of experimentation and technical development would turn domestic coal-burning into a homely art that is looked back upon with a degree of nostalgia. But it did not start out that way. Coal was not an easy fuel to use without the tools, techniques and appliances that were to come later.

Stoking the coal fire

The first problem was getting coal to burn at all. Tip out a pile of the stuff onto the ground and attempt to set fire to it without an accelerant and you will begin to see the problem. Now have a go at lighting a small wood fire directly on the same ground – a much easier proposition – and then add the coal on top; there’s a strong possibility the coal will still fail to take. It requires a fairly substantial and long-lasting wood blaze to get coal started. And once it has caught, your problems are not necessarily over.

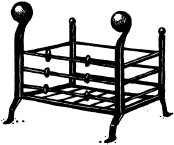

A coal fire flat on the ground can be a sluggish thing whose vigour is sapped by the build-up of its ash and clinker. Oxygen is the key factor here. Modern coal fires are burnt in a grate that exposes coal surfaces to the air by lifting the pile of fuel up off the ground and letting the ash and clinker fall away. Cold air is actively drawn up through the grate by the very act of combustion, with the rising heat creating a vacuum, or ‘draw’. This draught is transformative. Coal with and without the use of a grate is almost unrecognizable as the same fuel.

A simple basket grate is essential for coal-fire management. The grate lifts the coals off the ground, ensuring good airflow to the fire.

The people of Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire, provided as they were with high-quality, hard anthracite, probably managed to burn coal without a grate, but it was still hard work. It would have required a combination of adjusting the size and shape of the coal lumps and forming the wood of the initial fire into an open and supportive framework – akin to building a grate out of firewood. As the wood burnt away, discrete lumps of smouldering anthracite would maintain their shape, including the integrity of the air gaps between the lumps, allowing oxygen in to feed the fire. Most other coal would smother itself. George Owen sang his praise for the coal of west Wales, saying it ‘clyngeth not together’. For everyone else, dependent on the many varying grades and types of coal in the rest of the British Isles, burning coal without a grate was a frustrating business.

Now, people had long been aware that wood burnt better when lifted off the ground to encourage this draw. The simplest method was to use two ‘sacrificial’ logs set flat upon the hearth across which you balanced other firewood. As the fire burnt, the upper logs combusted merrily away, while the two base logs slowly smouldered or charred. New fuel was dropped regularly on top to sustain the blaze, while the base logs needed only infrequent replacement. Fire management involved keeping an eye on the overall shape of the fire and being ready to slot in a new base log when required.

One of the great innovations and status symbols of the Iron Age was to replace these two base logs with an iron fire support, or a pair of them. Archaeologists believe the earliest surviving examples of such iron supports were typically placed in the centre of a roughly circular open fire. These early irons were shaped something like a capital H. A cross bar was supported about 4 inches (10 cm) off the ground, with the firewood propped up and held at an angle in the middle of the fire circle. With pieces of wood propped up on both sides, a sort of tunnel was formed beneath the bar that encouraged cold air to be drawn in from both ends; the upright bars at the sides prevented the wood from rolling off.

This Iron Age firedog, discovered on a farm near Capel Garmon, in Conwy, Wales, must have been the property of a powerful chieftain; archaeologists estimate that it may have taken the smith about three years to construct it.

Thus the idea that raising a fire off the ground improves the rate of combustion was neither strange nor new. It may well have seemed an obvious thing to try. But it’s much harder to raise up burning coal than it is to raise up flaming logs. You need an extensive structure, one that is more complicated to manufacture, and which utilizes a lot more metal. For a long time it was probably not worth the effort or the expense to burn coal.

The problem with smoke

Once you got your coal burning, the next great technical problem to overcome was the smoke. Recall George Owen’s frustration with how ‘noysome for smoake’ most coal was. He was not alone in his ill opinion; coal smoke was universally detested. In the 1660s, John Evelyn called it a ‘feluginous and filthy vapour’. Other commentators said it was ‘noxious’, ‘unwholesome’, ‘unsavoury’, ‘offensive’ and ‘sulphurous’, an ‘arsenical vehicle’ with ‘corrosive particles’ that ‘annoyed’ and ‘corrupted’.

Peat smoke, wood smoke and coal smoke can all be difficult to live with and all are harmful to your health. But experience tells me that wood smoke is the least unpleasant and difficult to live with, while coal smoke is the most problematic. Peat, as mentioned earlier, produces large volumes of smoke that are particularly high in harmful fine particulates because it burns at lower temperatures. Peat smoke tends to create a much bigger if more diffuse cloud than does wood. The smoke is less visible and less distinct. One lives in a fine haze. Wood is more likely to burn with a hotter, clean flame producing fewer emissions, although this is partly dependent on how well the fire is managed. When the air is still, wood smoke rises with ease, leaving clean air at head height. Coal, in contrast, burns hot but produces a collection of chemicals that are particularly liable to hang low, gathering in places where people need to breathe. The high sulphur content of coal smoke affects the eyes as well as the lungs. When it mixes with water, a mild sulphuric acid is formed – what, on an atmospheric level, we call ‘acid rain’. The more immediate human experience is stinging eyes as the smoke makes contact with the wetness of the eyeball. When your eyes try to flush out the irritant by producing tears, the stinging gets worse.

The solution to the problem of smoke is the chimney, but most homes prior to about 1550 rarely had one. Domestic fires typically sat upon an open hearth in the middle of the room. All the heat generated by such a blaze was trapped within the living space while the smoke rose, cooled and slowly drifted up and out through any gap it could. Since windows were largely unglazed and roofs were generally thatched, a special opening in the roof was not always necessary. Smoke simply hung in the roof space until it could gently percolate out of the structure.

The quality and behaviour of smoke within domestic environments was no small matter. In the relatively still milieu of an interior space, wood smoke creates a distinct and visible horizon, below which the air is fairly clear and above which asphyxiation is a real possibility. The height of this horizon line is critical to living without a chimney. The exact dynamics vary from building to building and from hour to hour as the weather outside changes. Winds can cause cross-draughts that stir things up; doors and shutters opening and closing can buffet smoke in various directions.

Coal smoke is more like peat smoke in some respects and like wood smoke in others. Initially, when the exhaust from a coal fire is hot, the smoke is dark and distinct, rising and roiling like wood smoke but far more visible. Then as it begins to cool, it spreads out and drops somewhat, creating a more diffused atmosphere, present at all levels but becoming denser further up, like the smoke from a peat fire. Smoke management is one of those unspoken daily realities that we have next to no written record of, and yet it must have been a very pressing issue and life skill. From my experiences managing fires in a multitude of buildings in many different weather conditions, I can attest to the annoyance of a small change in the angle of a propped-open door, the opening of a shutter or the shifting of a piece of furniture that you had placed just so to quiet the air. And as for people standing in doorways, don’t get me started.

Over time households would have developed strategies for dealing with the prevailing winds, planting or removing trees around the house, blocking up old doors and windows and opening new ones in more suitable spots. They might even, where possible, adjust the angle and position of new buildings to take into account the local wind patterns.

But it’s not just about the wind. Temperature, air pressure and humidity levels have an impact as well. On cold, damp mornings, smoke hangs low to the ground, quickly losing the heat that helps it rise. Hot sunny afternoons, in contrast, help speed smoke up and away. Damp air acts like a lid, holding the smoke down. A rainy day means the smoke horizon drops; a clear frosty morning means it lifts. A well-managed wood fire in a well-managed home can produce a virtually smoke-free living experience so long as you are burning well-seasoned wood and are content to live life at ground level. No rooms above the ground floor was the norm during the era of open hearths. Naturally, there were moments when it didn’t go as planned, when gusts of wind blew the smoke into every corner of the room, or a bad batch of wood and a change in the weather pulled the smoke horizon uncomfortably – and dangerously – low. But in general, the situation was tolerable. People lived like this for millennia.

Replacing wood with coal, with no other adaptations to the home, made life a lot harder. Coal meant more smoke within the living area, and it meant smoke that stung the eyes and affected breathing. People burning coal upon open hearths probably coughed a great deal more and had to deal with running noses too. In short, until they came up with a new way of organizing their living structures, their lives became quite a bit more miserable.

The cost of wood

For reasons that historians cannot quite put a finger on, population growth in the sixteenth century was increasingly concentrated in just one place – London. Other towns and cities were growing, but at very modest rates. The imbalance became more and more marked, and the ancient city of London became both larger and more densely populated. The Domesday Book, completed in 1086 by command of William the Conqueror, reported London’s population as roughly 15,000 people. That figure rose to 80,000 before the plague struck in the mid-1300s and halved the number of Londoners. Gradually, through the first half of the sixteenth century, the city recovered, to about 50,000 residents. By the end of Elizabeth I’s reign in 1603, the population had quadrupled to 200,000. This urban population boom created unprecedented demand for fuel supplies with hardly any time for adjustments in the chains of supply. It was a crisis in the making.

Looking back at the dawn of the fourteenth century, when London’s medieval population was at its peak, we can see that problems with the fuel supply were already developing. In the decade between 1270 and 1280, for example, the price of faggots produced in the demesne of Hampstead, just five miles from London and listed among the accounts of Westminster Abbey, was 20d per hundred. Only a decade later, the same demesne was valuing them at 38d per hundred. Three manors in Surrey, all within 20 miles (32 km) of London, saw a 50 per cent rise in fuel prices between the 1280s and 1330s. The rising price of fuel is especially noticeable compared to the almost entirely stable price of wheat. Food supplies for the capital were keeping pace with demand, but fuel supplies were under pressure.

Nor was this simply a problem of haphazard and inefficient provision. A well-established and organized trade was in place, centred upstream from London Bridge around Wood Wharf, in the parish of St Peter the Less, and dominated by a group of men known as buscarii in the Latin texts – the woodmongers. These merchants had links with the owners of woodland and estates stretching far along the Thames and into surrounding counties. The closer these woods were to London, the more likely they were to specialize in short-cycle cropping.

Transport costs played a huge role in determining wood production in these areas. The bulkiest forms of firewood were bavins and faggots, both of which required a great deal of cart or barge space. Bavins, an especially small form of faggot used almost exclusively for lighting fires and composed of the smallest of twigs, could be produced in a single year; for the London market, they were produced primarily in Middlesex. Faggots arrived in the capital mostly from Middlesex, Surrey and Essex, as well as some of the more accessible parts of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Kent, not more than about 12 miles (19 km) away. There was little profit in carrying such bulky fuels any great distance but their relatively quick production cycle made them an appealing prospect to those with woodlands close to the city. Billets and tallwood held more value per load, so were worth the higher transport costs entailed in hauling them from more distant woods to market. Charcoal, being lighter and easier to transport, might come from as much as 26 miles (41 km) away. It was light enough to permit the use of a packhorse to carry the burden. To some degree, rising prices encouraged people from outside the capital’s usual wood-supplying districts to expand or redirect their business. But venture far beyond the reaches of the Thames and transport became much more difficult and costly.

By the mid-sixteenth century, when London’s population was once again nearing 80,000, problems in the supply of wood were reasserting themselves. Firewood prices were ticking up rapidly, outstripping price rises for pretty much every other commodity, and concerns were being voiced from many quarters. According to the Chronicle of the Grey Friars of 1542/3, the Lord Mayor of London was reported to have been visiting the wood wharves daily, putting pressure upon the merchants to supply wood to the poor at reasonable rates. A number of local government officials were trying to cut out the middlemen in an effort to hold down prices. Statutes were passed to address the cost and availability of both fuel and timber.

William Harrison, writing his Description of the Island of Britain in 1576, worried that firewood was running out, and that before long ‘broom, turf, gale, heath, furze, brakes, whins, ling, dies, hassocks, flags, straw, sedge, reed, rush, and also sea coal will be good merchandise even in the city of London, whereunto some of them even now have gotten ready passage and taken up their inns in the greatest merchants’ parlours’. These less desirable fuels had all been used at various times and in various places across the country. But London had grown accustomed to receiving regular commercial wood supplies via a sophisticated supply chain. The idea that Londoners might have to resort to the fuels of the rural poor was unsettling.

At this difficult and pivotal moment we get a snapshot of the capital’s fuel market from the probate inventory of Thomas West, a merchant, based in Wallingford, roughly 50 miles (80 km) from London (then in Berkshire, now in Oxfordshire), who died in 1573. The inventory includes a long list of his debts and business dealings over the last eight years of his life. West seems to have had depots upstream on the River Thames at Burcot, where he had an agent working on his behalf, and at Culham, just south of Abingdon, in Oxfordshire. Downstream, he maintained a presence at Pangbourne, in Berkshire. He moved a reasonable volume of agricultural produce (around 20 per cent of the entries that specify any particular good), a small but noticeable amount of fish (6 per cent) and a fairly sizeable volume of coal (20 per cent). But the main bulk of his business, representing 40 per cent of the entries that specify any particular good, was in transporting wood down the Thames towards London. In fact, West’s wood, and most of his agricultural produce, was sent downstream, while the fish and coal, along with a myriad of tiny quantities of various other goods, came upstream, out of London, before being distributed to settlements across the surrounding countryside.

Fifty miles – the actual journey following the course of the river is actually considerably longer – is an awfully long way to be shipping firewood, yet that was what the majority of West’s wood cargoes seem to have consisted of. Reference was made in some cases to ‘timber’, meaning the much higher value, large straight pieces of wood used by the construction industry, but much of the wood was described as billet or tallwood. An important part of his trade involved supplying the royal court in London with firewood. While this may well have involved some gratifyingly large orders, it did come with its own difficulties. A significant number of the debts listed in his probate inventory were from the Board of Green Cloth and its assignees. One of these debts, incurred by John Manwood on behalf of the royal household, had been outstanding for two years and was recorded as having been partly paid off in cheese!

The vigour and extent of Thomas West’s trade in firewood in a region so far from the city centre mirrored contemporary records of rising prices and elite concerns. London was looking to augment its fuel supplies by reaching further out, and as a result, was forced to pay the higher transport costs involved. But what of the coal that West was also shipping? This coal was travelling out of London and being delivered to a variety of landings and stagings along the river’s banks. Most of the coal debts in West’s inventory were from blacksmiths. It was the smithies’ trade that he was supplying, and he was doing so with coal purchased in London.

Coal had certainly arrived in London by the turn of the thirteenth century. Several records mentioned it being used by lime burners in 1180. Within fifty to seventy-five years, London smiths were using coal sufficiently regularly for it to become the specialist cargo of a few wharves downstream of London Bridge – and for it to attract the attention of the tax collectors. It came in the main from the outcroppings of surface coal in and around the Tyne and Wear estuaries.

By sea or by land

Britain is very well endowed with coal deposits. There are the easily accessible anthracites of south-west Wales; large deposits of differing types of coal running in broad bands across much of south Wales; and another, smaller deposit in the north, on the coast in Flintshire. Scotland has coalfields that stretch in a belt from Ayr to Glasgow, Stirling, Kirkcaldy and Edinburgh. Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire are blessed with their own swathe of accessible coal, while smaller coalfields are scattered throughout the Midlands at Wolverhampton and Stoke-on-Trent and to the north of Manchester. On the north-west coast of England lies the small coalfield around Whitehaven, while the area around Bath and Frome and that around Coventry are the two sources of coal that are geographically closest to the capital.

But in the early days of the trade, London drew its coal almost exclusively from Newcastle. For all that Newcastle seems remote from London, it had the closest of the outcroppings by the sea route to London. In some places near Newcastle, the coal was right on the water’s edge, eroding out of the cliffs and riverbanks to be gathered on the beaches. Simple and cheap to extract, sea coal was also simple and cheap to load onto boats and carry to other ports.

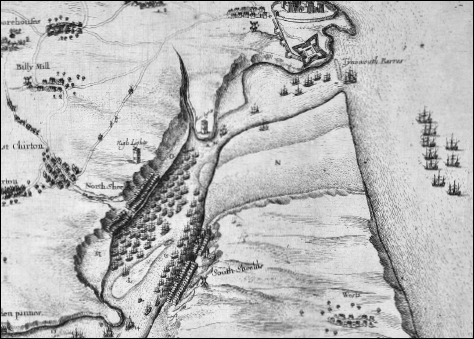

The River of Tyne Leading from the Sea (c. 1651) by Wenceslaus Hollar, showing ships waiting to be loaded with ‘sea coal’ for the journey to London.

Scotland was three days’ sail further north and, as a separate country then under its own king, it was often politically at odds with England and Wales. So, very little Scottish coal made its way to London in these early years. The Welsh coalfields, despite fewer political and trading difficulties, were nearly twice as far from London by sea than Newcastle, and the voyage involved piloting the dangerous seas around Land’s End. Overland transport meanwhile was extortionately expensive in comparison to transport over water. If you spent £1 on coal at the Newcastle pithead, it would cost you a further £3 to ship it to London, 250 miles (402 km) away. If you asked a carter to transport your £1’s worth of coal overland, £3 would get it less than 10 miles (16 km) from your starting point. In other words, London was lucky. Coal could be had in the heart of the city at the same sort of cost that would have prevailed if a great surface outcropping had naturally occurred within a 10-mile radius. To all intents and purposes, there was an untapped fuel resource sitting on the capital’s doorstep.

This was not the high-quality anthracite of Pembrokeshire, but a softer, more sulphurous version that caked when burnt and gave off a plentiful supply of stinging black smoke. Still, it suited the needs of the lime burners and the blacksmiths very well, despite the plentiful complaints about the smoke from their neighbours in local records.

London’s lime burners, who supplied lime mortar for the building trade and limewash for paint, liked the sea coal from Newcastle because it was a more concentrated form of fuel than wood and was cheaper than charcoal. Limekilns work best with large batches of fuel. The fuel is stuffed into the bottom of the kiln with limestone packed on top, followed by more fuel and limestone, in alternating layers. Once the kiln has been filled, the fire is lit. The heat initiates a reaction with the limestone (calcium carbonate), producing both carbon dioxide and lumps of calcium oxide. After the fuel has burnt away and the carbon dioxide has wafted into the atmosphere, the limestone has, hopefully, been converted into pure quicklime (calcium oxide). Coal neatly packed into a kiln takes up far less space than does wood, and it burns long and steady, releasing more heat and thus ensuring more limestone is converted to quicklime in each campaign of burning. It also allows for near continuous production, since more layers can be added to the top of a burn as the finished material is removed from the bottom.

As far as the early lime burners were concerned, the ideal coal was a so-called ‘nutty slack’ – some of the cheaper, more broken-up loads of coal from Newcastle. The ‘slack’ was essentially coal dust, while the ‘nutty’ elements were small lumps of coal mixed in. For each 5 inches (12 cm) of depth of nutty slack shovelled into a kiln, around 10 inches (25 cm) of limestone was loaded on top of it. Many builders considered the quicklime produced with nutty slack to be a superior product to that produced with wood.

For blacksmiths, the caking qualities of Newcastle sea coal were invaluable. Recall how smiths can create different shapes of fire, including a sort of cavern or oven shape. Watered and tamped down, fires of sea coal could be shaped very accurately to provide particular areas with precise temperatures. The ash and clinker could also be manipulated within the forge to a smith’s advantage, creating cooler areas to rest the work, or acting as insulators around hot spots. And most importantly, coal didn’t burn away as rapidly as its main historical rival, charcoal.

By the time of Elizabeth’s reign, word had spread across the country of the technical advantages of burning coal in these two industries. As a result, wherever a supply could be had at not too great a cost, coal was finding a market. Thomas West’s customers in Berkshire and Oxfordshire were among the lime burners and blacksmiths who had heard about the wonders of coal. His coal was certainly well-travelled, having been gathered near Newcastle, loaded onto a barge and carried down the Tyne, reloaded onto coastal vessels for the journey down to London, then transferred back onto a barge and sailed up the Thames.

Chimneys and their cousins

Two key technological developments were needed to transform domestic coal-burning from a difficult, horribly smoky experience into a daily ritual that could be not only tolerated but adopted across the city: the iron grate and the chimney. Of these, it was the chimney that involved the biggest and most immediate investment and upheaval in living arrangements. And again, a certain serendipity came into play.

Castles, monasteries and other great houses began to have chimneys not long after the Norman Conquest. But building in stone, even just the stone for a chimney stack, was supremely expensive, and for centuries, chimneys were restricted to the super elite. There were very few people living in stone dwellings, with the majority of even the aristocracy living in more traditionally British wooden abodes.

These earliest chimneys were perhaps viewed more as status symbols, following imported patterns rather than developing organically to solve a domestic problem. A fire on the floor in the centre of the room is very heat efficient. All of the energy released by the fire radiates out evenly into the living space. Chimneys, on the other hand, channel around 70 per cent of the heat of a fire straight up and out of the building. Moreover, these structures are typically located at the edge of the room, creating an unevenly heated space. They also produce a draw, which sucks cold air in at the base, creating a cold draught at floor level. With so much inefficiency built into the design, those who built chimneys needed considerable means to contend with the original capital investment of building and the significantly higher ongoing fuel costs. It came down to a choice of burning considerably more fuel or accepting a much colder home.

London may well have been at the very forefront of the development of the chimney in more modest homes. Chimneys began to be mentioned in London with some frequency in documentary evidence from the fifteenth century. Regulations gathered together and copied out in the Liber Albus of 1419 by John Carpenter, the town clerk of London, insisted that chimneys should no longer be made of wood. Instead they were to be constructed of stone, tiles or plaster. It’s not clear if these were chimneys in the modern sense, or one of a myriad of ‘interim’ chimney forms being experimented with. There is less ambiguity in the will left in 1488 by a London mason called Stephen Burton. It included a stock of pre-made stone fire surrounds, known as ‘parells’, that were meant to be inserted into the chimneys of his wealthy customers. Images from the mid-sixteenth century – including the famous Wyngaerde Panorama of 1543/4, another panorama of London by an unknown artist made c. 1550 and held by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Agas map of 1561 – clearly depict a considerable number of chimneys on the city’s skyline. However, a certain, very inconvenient fire in 1666 destroyed the vast majority of the physical evidence of them.

Detail from the map of London, drawn by surveyor Ralph Agas in 1561, showing the area around Southwark, London Bridge and the Tower of London. Already, a number of buildings had chimneys.

Domestic chimneys did not sprout up all at once, although it may have sometimes seemed that way to contemporaries. For instance, in 1577 William Harrison of Essex reported fussily on the ‘multitude of chimneys lately erected’. The old men in his village remembered ‘in their young days there were not above two or three, if so many, in most uplands towns of the realm (the religious houses and manor places of their lords always excepted, and peradventure some great personages)’. Instead, Harrison wrote, ‘each one made his fire against a reredos in the hall, where he dined and dressed his meat’.

Not everyone made the switch from open hearth in the middle of the room to a chimney set against a wall in one fell swoop. There were a range of considerably cheaper ‘transitional’ forms that were much less disruptive to instal. Harrison’s reredos were a sort of fireback, generally chest high and 4–6 feet (1.2–1.8 m) long. In some places it was a large flat upright stone, but it could also be a short section of fire-resistant wall, even one of wattle and thick daub, against which the fire was built. The short wall helped channel air around the fire and was particularly useful in counteracting the sudden changes in draught caused by opening and closing a door.

Central hearth with reredos in a croft on Birsay, Orkney (photograph c. 1900).

Another option was the smoke bay, which the people of Kent seem to have found particularly congenial based on the number of homes sporting them between the end of the fifteenth century (when wood was still king) and the mid-seventeenth century (when coal began to arrive). A smoke bay was created by the addition of rooms within part of the roof space, leaving a smaller, more constricted but still open passage for smoke to rise up from the fire to the rafters.

Sketch of the layout of the interior of the Weaver’s House at Spon End, near Coventry, with the smoke bay above the main hearth and a first-floor room to the side, providing a smoke-free living space that also helps to channel smoke up into the rafters.

An especially good survivor of this sort of domestic arrangement, in an unusually ordinary and modest home at that, can be found in the Weaver’s House in Spon End, near Coventry. The house was built in 1455 by Coventry Priory as a speculative investment, one of six in a continuous row, or terrace, intended to be rented out to local craftspeople. On the ground floor at the front there is a reasonably sized room that would have been the hall or ‘houseplace’. This room would have contained the home’s hearth, either located in the middle of the room or, given the modest space, pushed to the room’s side with a reredos behind. The other ground-floor room is the size of a small bedroom. It is presented today with a small bed in situ, but it may have been used as a buttery, a storage area for foodstuffs and household equipment like tubs and churns. From this room a steep staircase – more a ladder, really – ascends to the only room on the first ‘floor’. This room is a little larger than the room below it and overhangs part of the hall. It currently houses a loom and may well have been a dedicated working area. The timber frame indicates this was the building’s original configuration, with one upstairs room perched in the traditional smoke space, usable because the walls seal it off from the area over the fire. The smoke from the hearth was left free to waft about and percolate its way out through the roof, untrammelled by any sort of chimney.

Another urban model can be found in Tewkesbury among the Abbey Lawn Cottages. Managed by the John Moore Museum, the Merchant’s House is one of a row of late-fifteenth-century buildings. Open to the public, it is presented with its original room layout, including a large hall open to the roof but partially subdivided by an upstairs room.

I have been lucky enough to spend time in buildings with a smoke bay, cooking, brewing, baking and generally hanging out doing historic stuff. The effects of these structures for managing smoke are intriguing. The areas beneath the jettied-out upstairs rooms were considerably less smoky than those areas open to the rafters. The smoke bay changed the normal flow of air within the space. The upstairs room acted as a lid, preventing the air beneath the jetty from rising, and causing it to become really still, so that very little smoke gathered there. The air in the open area could rise freely and move out through the roof, which ensured the smoke-laden air was usually drawn up and away from the fire. Despite there being no physical barrier between the two areas up to first-floor level, the two bodies of air barely commingled. One created a gentle, upwards-moving, smoke-laden current, the other a static, smoke-free volume.

Differing more in degree than in fundamentals was the smoke hood, another halfway-house smoke management system. A fine one can be found in the Avoncroft Museum of Historic Buildings in Bromsgrove. The fifteenth-century town house has a hall with a hearth located in one corner. Over it sits a large wattle-and-daub hood, roughly 6 sq. feet (2 sq. m), which ushers smoke up and away. Though the hall remained open to the rafters, the hood reduced the amount of smoke that gathered in the room, and because there was no constriction around the fire itself, no great draw was created. Like the smoke bay, the smoke hood was more of a smoke collection and channelling apparatus.

Constructed of wattle and daub, lath and plaster or wood, a smoke hood could be easily inserted into the home, at much less cost than a true chimney.

Those smoke hoods which have survived are generally constructed of wattle and daub, lath and plaster or wood – the sort of chimneys described in the Liber Albus regulations. They were typically sited about 6 feet (2 m) above the fire, or at ceiling height, and continued up through the building to an opening in the roof, much like a primitive chimney. The fairly wide funnel they create – usually between 4–6 sq. feet (1.2–2 sq. m) – allowed the smoke to cool as it ascended, meaning that the smoke hood was much less likely to catch fire than people today often expect.

If you are burning wood, a hood offers distinct smoke management advantages over an open fire, without costing too much in terms of construction or ongoing fuel costs. It is also relatively easy to insert one into an existing building. Without a draw, the majority of your fire’s heat remains within the room, and with no ground-level side walls, your access to the fire for cooking is fairly free. A hood is less of a help in controlling coal smoke, which is much less eager to rise once cool, nonetheless there is something to be gained from one.

That simple smoke hoods were often called ‘chimneys’ in period sources is made clear by the accounts for the construction of a ‘chimney in widdowe Cox her house in Saltisford’ to provide separate accommodation for ‘Widdoe Whood’ in the same building. A carpenter was employed for four days, along with two sawyers for one day, and a load of rods and laths was bought in order to insert this new ‘chimney’. Once the chimney had been built, a tiler by the name of Barnes was paid to ‘tear’ the chimney and make the hearth. Constructed of a combination of sawn wooden planks as well as the rods and laths, and then plastered, with a hearth that was probably lined with tiles, the whole accommodation could be inserted into an existing building quite quickly.

When I think about these changes in the home, and the uneven and ad hoc nature of the solutions people were devising to address common domestic problems, I am reminded of the great double glazing and central heating installation frenzy of my own youth. Central heating systems had been in use in churches and grand houses in Britain for nearly a century, but in the 1960s, most people’s homes still relied on coal, gas or electric fires that essentially heated only one room. Then, suddenly, things began to change. By 1970, 30 per cent of homes in Britain had some form of central heating. Double glazing, originally a Scottish idea, became quite popular in the 1970s and really took off with the introduction of a uPVC version in the 1980s. Within a couple of decades both had become widespread. Central heating take-up was particularly quick: by 1990 around 95 per cent of homes had a system, a proportion that has remained pretty stable to the present day.

Many families went through a stage of having partial central heating systems, which didn’t reach all areas of the home, or of having ‘secondary’ double glazing, which involved fitting a relatively cheap extra layer of window over the top of your existing panes. It didn’t look as neat, or have quite the thermal efficiency of true double glazing, but it involved much less expense and disruption to instal. New builds, however, soon came to include both central heating and double glazing – initially as much vaunted and advertised selling points, and later as standard features.

These changes had a profound impact upon the way homes are utilized. When heat was available in just one room, there was a distinct pressure on families to spend time together communally in this single space. As the heat spread out, so did the inhabitants. The rise of games consoles and on-demand entertainment systems, for example, probably owes as much to the rise of central heating as it does to any other technology. There have been a whole host of other indirect responses. Larger houses with more bedrooms and other separate spaces became more attractive propositions when all of those spaces could be heated, fuelling a boom in construction. Meanwhile, bathrooms have become much more desirable places, ones in which people are willing to spend more time, helping to stimulate the personal care industry.

With the benefit of hindsight, these overhauls of living spaces and lifestyles appear to be obvious, perhaps inevitable improvements, part of the great forward march of technology. Living through such a transformation, however, feels much less obvious, inevitable or even all that beneficial. The changes were costly; people vacillated over whether or not to make the improvements, unconvinced that they would see any long-term pay-off. Early adopters struggled to learn how to use the new systems. Others held on to the traditional ways out of emotional attachment. But once the ball started rolling, neighbour followed example of neighbour, and homes and home life were reconfigured.

Back in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a similar pattern held. Architectural surveys of the old housing stock of the British Isles show an enormous volume of adaptation and remodelling of homes in order to include chimneys where once there had been none, particularly between 1550 and 1650. In the more prosperous south-east of England, including William Harrison’s village in Essex, where reredos were being lamented, such changes came early. In remoter and poorer districts further from London, the changes came a little later.

People adapted their homes in fits and starts, as they could afford, especially within the urban environment. Reredos were cheap and easy to instal. Smoke bays required much more investment and greater upheaval but were undoubtedly more desirable, since they increased the amount of living space with the insertion of the upstairs room. Both the Weaver’s House at Spon End and the Merchant’s House in Tewkesbury were built as speculative ventures. They were designed to attract rent-paying tenants and offered with the ‘new’ smoke bay layout as standard – much as builders of the early 1980s included central heating and double glazing in their developments. The speculators knew that more and more people would want these features in their home.

First movers (and furnishers)

Already the most densely populated city in Britain, the pressure to maximize living space was always strongest in London. Smoke bays and smoke hoods, including those ‘wooden chimneys’ banned in the Liber Albus, were steadily being replaced by substantial true chimneys built of stone or brick. As early as 1370, a row of eighteen shops built by the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s next to their brewery boasted a chimney on each unit. The contract for the mason specified ten chimney stacks, eight of which were attached to doubled, back-to-back fireplaces facing into two separate retail units, thus serving all of the properties. The fireplace surrounds were to be lined with Flemish tiles and the hearths were to be of stone and tile shards.

In homes where chimneys had been installed during the wood-burning era, the desire for more heating may have been a spur to switch to coal. A fireplace was fixed in size by the brick- or stonework and its chimney. A roaring blaze could be expanded only up to a point. There was a very real limit to the amount of fuel you could add to your fire. If you wanted more heat to compensate for the 70 per cent that was escaping straight up the chimney, you needed to burn something that produced a hotter flame. Coal delivered more heat.

Another complementary response to the heating problem was to subdivide your space. If you could no longer afford to heat the whole of your living accommodations with a single central hearth in an open hall, you could at least heat one portion of it around a fireplace, walling the immediate area in to trap the heat. The rest of the house might well be freezing, but you had somewhere to thaw out at the end of a hard day.

There was also the issue of furniture to consider. With an open central hearth the most comfortable area within the home is close to the floor. Sitting in a tall chair on a rainy day, when the cooler, damp air pulled the smoke horizon down low in the hall to below your chin, ensured bouts of coughing and spluttering and general discomfort. It was much better to furnish your home with low stools, or better yet, to cover the floor with a warm, insulating layer of soft rushes and sit directly upon them. The same approach was taken to sleeping arrangements, with your ‘bed’ (what we would call a mattress or pallet) placed directly on the floor.

Surviving probate inventories hint (but no more than hint) at these practical realities. It is extremely hard to tell from a list of someone’s possessions at the time of their death whether they were living in a house with or without a chimney. The buildings were rarely described in detail. That was not, after all, the purpose of the document; it was not a bill of sale. You can make a reasonable guess about how many separate rooms there were by the way items were grouped together and many, but not all, inventories did name some of the separate spaces. References to ‘upper chambers’ are particularly suggestive. In a few, very rare cases, it’s possible to link an inventory with a surviving building. There does, however, seem to be a loose relationship between central hearths and small, low furniture in regions where the surviving houses show that chimneys were only adopted late in history. Similarly, there seems to be a relationship between chimneys and rather more substantial volumes and styles of furniture in regions where the still extant buildings show earlier chimney adoption.

It wasn’t just that central hearths discouraged tall, substantial furniture; chimneys actively called for it. The floor-level draught that a chimney produced was no pleasant thing if you had to sit and sleep on the floor. Once you had installed a chimney, you were subject to a cold insinuating incentive to visit the carpenter and invest in some furniture that could raise you up a few inches. Bedsteads that lifted your mattress or pallet up off the newly draughty floor significantly improved your comfort.

These everyday practicalities actively slowed the adoption of chimneys when wood and peat remained the dominant domestic fuels. Building a chimney alone entailed a large initial outlay in building works. With new furniture added to the costs, a chimney more than doubled people’s bills. Chimneys were worth this financial burden for the Norman monarchy, upper aristocracy and religious houses, all of which sought to make a statement about their superior cultural heritage through the sophistication of their buildings. These elite were naturally more likely to invest their wealth in large ‘statement’ pieces of furniture such as thrones and banqueting tables. They used their rooms for ceremonies and other large gatherings of people. A chimney, housing the fire at the side of a room rather than in the centre, was an asset in such spaces if only for snob value. The reduced heat could be easily mitigated by burning enormous quantities of wood and, later, coal.

But if these were the practical issues surrounding chimney installation there were also more nebulous cultural questions. Take, for example, Penshurst Place, the home of Sir John de Pulteney, a very wealthy Londoner who was elected mayor of the city on four separate occasions. Built in 1341 on a grand scale with no expense spared, it is a stone-walled building whose great hall measures 60 x 40 feet (18 x 12 m). The hall is capped by a magnificent 60-foot-high chestnut beamed roof. High tracery windows provide a lovely light. At one end of the hall lies the ‘solar’, or private family wing. Here Sir John and his family could retire from the public congregating in the hall itself. At the other end of the hall are the remains of a service wing, now comprised of a buttery and pantry along with a passage that once led to the kitchens (sadly demolished). Despite very ample financial resources, and the example of a couple of centuries of chimney experimentation around Britain in buildings of a similar status, the Pulteney family chose to erect a central hearth in their brand-new, statement-piece hall. Hearths were ancient symbols of home and hospitality, stability and tradition. They harked back to the days of chieftains and feasting. Good fellowship, open and honest dealing and strong community values were all embodied by gathering around an open central hearth. There may even have been a feeling that a fire in a chimney was an indication of a withdrawal from the common good, a selfish layout that restricted warmth – literal and proverbial – to a small group clustered in front of it, leaving everyone else out in the cold.

The Pulteneys were an exception among the elite, but their choice reflected the status quo. For most people across wood-burning Britain, warmth produced cheaply was much more valuable than stone cold status. Affordable heating throughout the living quarters of a home was worth the unpleasantness of the handful of smoky days to be expected from a central hearth.

There were, however, several rather powerful and practical points in favour of chimney technology. A chimney reduced the amount of smoke at ground level, where people were used to living, but even more radically, it did so higher up in the room, lifting the smoke horizon. With a chimney it was possible to make use of the space above head height. A full upstairs area could be employed in the home, doubling or trebling the size of your living space within the same four walls. This was a very attractive prospect for families packed cheek by jowl in tight, often awkward urban plots. Chimneys also offered improved fire safety – a boon after the Great Fire.

So, near the end of the sixteenth century, the pace of chimney building began to accelerate. It began, as we have seen, in the prosperous south-east, where more people could afford to invest in a status symbol, and in London, where population pressures were changing the economics of housing. With more and more people living in the capital, rents were rising and more people were squeezing onto each and every piece of land. The only option left was to build upwards. A three- or four-storey building was increasingly the norm in London. With rooms stacked upon rooms, smoke control became essential.

Perhaps these two factors – a mixture of social aspiration and fashion in the countryside with the population pressure upon urban living spaces – would have been enough to usher in chimneys right across the country. But there was a third driver: coal. While coal cannot be blamed or lauded as the originator of the move over to chimneys, it was central to the spread of this new approach to inhabiting the indoor realm. If you wanted to burn coal in your home, you were going to have to find a way of dealing with the sulphurous and particularly low-hanging smoke. Chimneys were the answer.

Once a household made the switch to coal, they quickly found many good reasons to build, maintain and upgrade chimneys. Because coal burns hotter than wood, the resultant smoke is hotter too. The smuts get sticky in a way that wood smuts and ash do not. Coal smoke also lays down a thick black coating upon the surfaces of any flue that it passes through. Hot and clogged with combustible soot and coal tar, the chimneys used while burning coal are therefore at higher risk of catching fire than those used while burning wood. The makeshift wood-and-plaster smoke bays and smoke hoods were much more vulnerable to catching ablaze once people adopted coal in the home. Experiments in smoke management like the smoke bay and smoke hood facilitated the uptake of coal-burning in more homes, since they made it marginally safer to use this fuel. But these interim systems were soon shown to be insufficient, resulting in the adoption of substantial, sealed brick- and stonework chimneys in even modest abodes. These true chimneys created more of a draw, keeping the air clearer of smoke but pulling in cold air at ground level. This in turn encouraged people to invest in more furnishings and subdivide their spaces. By this point, they were committed to this new fuel and its accompanying lifestyle.

The shift from wood to coal thus transformed homes from bigger open spaces where a wide range of activities took place into collections of several smaller, furniture-filled rooms. It is only now in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, with central heating, that the spaces in which we live are once again widening and broadening.

As London’s population surge took off in earnest, we see a city where the lack of space was already encouraging a patchwork of developments in fire and smoke management. More than anywhere else, the capital’s residents had a good number of homes that could cope with coal reasonably well. Others, if not exactly perfect, were better equipped than most of their rural brethren to deal with the foul, acrid smoke of their new fuel of choice. But once Londoners made the switch, the rest of the country followed.