It is the gathering of taxes upon the imports of Newcastle coal which gives us our clearest picture of the big switch that was happening in the great capital. Until the mid-sixteenth century, somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 tonnes of coal was arriving at the city wharves annually. This then is our baseline: the amount of coal sufficient to fuel a couple of specialist industries within the city and supply some forward-looking (and relatively prosperous) blacksmiths along the upper reaches of the Thames.

By 1581/2, however, a dramatic rise was under way. That year, 27,000 tonnes of coal arrived. By the end of the decade, the haul was close to 50,000 tonnes annually. After that, the trade increased by leaps and bounds: 68,000 tonnes in 1591/2, 144,000 tonnes in 1605/6, 288,000 tonnes in 1637/8. By the late 1680s, more than 500,000 tonnes of coal was landing upon the city shores – and being taxed.

When you plot the rise in coal imports alongside the rise in London’s population, the picture becomes even more dramatic. As early as 1577, William Harrison, in An Historical Description of the Island of Britain, noted that coal use ‘beginneth now to grow from the forge into the kitchen and hall’. In the mid-sixteenth century, when the population hovered somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 people, less than 20,000 tonnes of coal were brought into the capital, enough for approximately one quarter of a tonne per capita. By the 1610s, when the population stood at a little over 200,000, there was three quarters of a tonne of coal available per person. It was as if each individual Londoner was consuming three times as much coal as had their parents, and now there were twice as many Londoners as there had been then.

But was this increase in coal consumption really down to individual Londoners? Historians who study the development of the nascent coal industry are convinced that, in the main, it was – or, at least, it was down to individual households. John Hatcher, for example, concluded that ‘the most important transition of all was the progressive adoption of coal for domestic heating’. Similarly, William M. Cavert argued that ‘the early modern world’s leading coal market was driven primarily by domestic rather than industrial consumption’.

Coal on the horizon

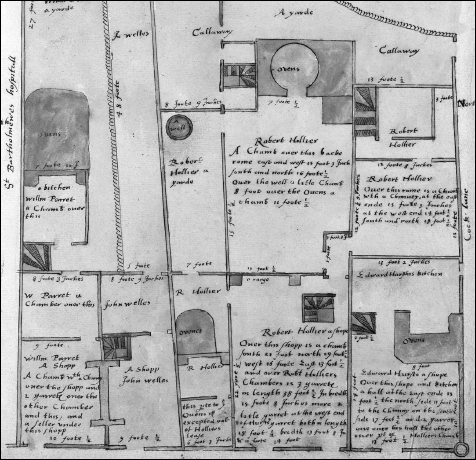

Another way of looking at the question is to take a close look at London itself during this transitory period. As a first stop, consider the view of London taken from the property surveys drawn up by Ralph Treswell around 1610. Treswell, a member of the Worshipful Company of Painter-Strainers, had managed to pick up the skills of a surveyor and cartographer and gained employment drawing up plans of land holdings and buildings. In central London his two main clients were Christ’s Hospital and the clothworkers’ guild, storied institutions that owned large and varied portfolios of sites within the city that they rented out to a long and equally varied list of tenants. Treswell’s surveys give us a detailed portrait of London’s housing stock before the Great Fire swept almost all of it away in 1666.

Survey of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane taken by Ralph Treswell for Christ’s Hospital Evidence Book (1611). We can see ovens, fireplaces, and ‘a range’ in the centre.

All of his surviving plans depicted the ground floor of the building, although many contained notes about the number and name of the rooms above. He differentiated between stone walls, brick walls and ‘standard’ walls (presumably, timber-framed walls with wattle-and-daub or lath-and-plaster infill). Wooden fences were also represented. Every well was marked, and so too were ground-floor privies and staircases. Most excitingly for our purposes, he also marked the fireplaces.

These were not generic symbols. Each fireplace was shown with its position within the room. The illustrations varied in size according to the size of the fireplace, and differing thicknesses of brickwork were carefully drawn, with a number of unusual shapes, alterations and adaptations discernible. While some included ovens, many did not. For those with ovens, the oven doors were depicted, some facing in to the fireplace and others facing out to the room. There were no central hearths marked for any of the properties, nor was this simply an oversight, as almost half of all the ground-floor rooms in the surveys had a fireplace instead. In fact, I have yet to find a room described as a ‘kitchen’ that did not have a fireplace.

There were brick fireplaces in rooms named as chambers, halls and parlours; in wash houses and a few shops, which were perhaps catering establishments; and in drinking rooms in taverns and alehouses. They also appeared in many rooms labelled only with the name of the tenant.

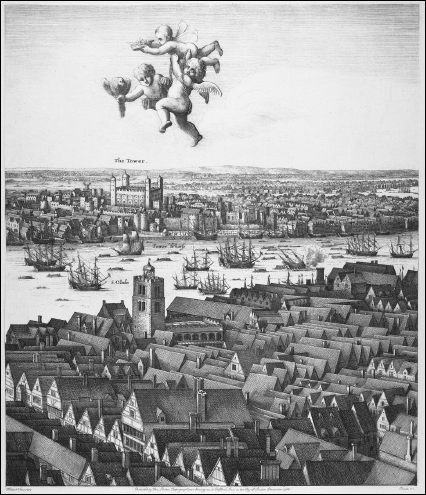

Thirty years later, London, as drawn by Wenceslaus Hollar, bristled with brick chimneys, very much in line with Treswell’s interior surveys. Between the mid-sixteenth century and the mid-seventeenth, a generous scattering of chimneys had grown into a positive forest of them. Did a city that was already practised in building brick chimneys experience a chimney-building spree as more and more people made the switch to coal starting around the 1570s? Or did the existing chimneys encourage households to start using coal? Or could it have been a bit of both? Either way, by 1610 London was a city superbly, and perhaps uniquely, equipped for domestic coal-burning.

As London switched to coal, worries about the supply of wood faded somewhat. Wood was increasingly expensive, but so many were using coal, particularly in poorer households, that it was changes in the price of coal that now needed to be watched carefully. In 1601 the Privy Council tried to reassure the Lord Mayor of London that Her Majesty took concerns about coal supply very seriously and was well aware that high prices could have serious consequences for the capital. By 1610, Parliament described coal as the ‘ordinary and necessary’ fuel of the city, ‘spent almost everywhere in every man’s house’.

Detail from A Long View of London from Bankside by Wenceslaus Hollar, showing the proliferation of chimneys across the city’s skyline by 1647.

Throughout the city, households had made the switch from being wood-burners to being coal-burners, and there were more Londoners than ever before. The change proved to be both swift and for the long haul.

For every man, woman and child?

By 1600, London was a coal city and would remain so well into the twentieth century. And as the city grew, its appetite for coal grew with it. It would be illuminating to be able to see how exactly the big switch occurred for this generation of Londoners and how it remodelled city life. But beyond the bare totals, we know very little about the dynamics of how each household made the decision.

We do not know for certain which sectors of the population were quickest to change. Was it the poor, the middling or the wealthy who first decided to use coal instead of wood? Did dockworkers, blacksmiths and lime burners, who had greater access to coal, carry a bit of this fuel to their homes, and its use spread from there? Was there perhaps a small community from a traditional coal-burning area – like Pembrokeshire – who introduced it to their neighbours? We have nothing to tell us whether people made the move incrementally or wholesale, if some swapped completely or if most mixed their fuel consumption, at least for a time.

Nor do we know who within the household was responsible for making the purchase. When it came to spending money, men were typically in charge of all large capital expenditures, such as the purchase of land and livestock, while women took responsibility for day-to-day expenses of items like bread and candles. Fuel supplies sit right on the gender divide. A large stock of fuel to last the year might be a capital outlay; smaller, weekly deliveries more like the purchase of cheese and butter. Was the switch to coal led by men or women? It is an intriguing question – and unanswerable at present.

In his influential volume The Industrious Revolution, the historian Jan de Vries looked at consumer behaviour and household economy since 1650. Although he did not cover fuel use, he highlighted the importance of considering ‘the behaviour of ordinary working people in the context of their aspirations and of their choices. This is not to deny that these choices are often highly constrained, but it does reject the view that they do not exist.’ Such a way of thinking reminds us that simply because coal was much cheaper than wood, this does not necessarily mean poorer members of society switched to it. Choices were available to them: they could use coal exclusively, prioritize certain wood-burning occasions, skimp heavily on some other expense to fund a wood habit, use a mixture of fuels or manage without any fire at all. I would argue that the figures themselves hint at a complex collection of choices.

An average consumption per head that rises from one quarter to three quarters of a tonne of coal annually within thirty years speaks of a significant aggregate shift, but three quarters of a tonne per person leaves quite some room for individual decision-making. I asked two solid fuel suppliers about average orders today, and modern demand suggests that a single fire used only during the winter months in an efficiently designed grate and chimney consumes about 2 tonnes of coal. People who try to heat both their home and their water entirely by coal generally use more than double that amount. Those who use a coal-fired AGA or Rayburn range as their main cooker tend to go through between 3½ and 4½ tonnes annually.

Of course, in the past people typically lived in households rather than separately, so if we want a more realistic picture to measure against the modern experience we must lump together individual shares of average coal usage. According to the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, the average household size in the late sixteenth century was around 4.75 persons, although the figure may have been more or less in urban contexts. There was also a small amount of coal use in brewing and other industries, which historian William Cavert has estimated at just under one quarter of London’s total coal supply. So, the average household would therefore have consumed around 2½ to 3 tonnes of coal per year. Based on modern experience using coal, this level of provision would have allowed each household, with careful management, to maintain one coal fire sufficient to cook upon throughout the year.

Slightly more rooted in reality are the rations of contemporaries. In 1620, the bakers’ guild described the typical member’s household as including a master, mistress, children, servants and apprentices, and declared that for a year they needed four ‘chaldrons’ (or ‘chalders’) – a measure specific to coal that is just under 6½ tonnes. This household would have been larger and more prosperous than the average in London, keeping a warmer home and doing a great deal more cooking. Compare it to the almshouses maintained by the merchant tailors’ company, who gave one chaldron (just over 1½ tonnes) to their resident almswomen, or those kept by their less generous compatriots, the brewers’ company, who doled out half a chaldron.

One indication of people making choices about where and how they spent their money can be seen in the plethora of commercial catering establishments, from pie shops to taverns, dotting London. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Londoners who required no fire at home, whether on a particular day or as a regular habit, could bring home a takeaway or eat out. It might seem odd that a poorer person would choose to eat out rather than cook at home, but after factoring in fuel costs, the time spent cooking (rather than being engaged in money-earning work) and the likelihood of living in crowded accommodation without basic facilities (such as a chimney), then daily bread from the baker and the occasional hot pie from the shop on the corner, washed down with a jug of ale, was a sensible option. If they did not need to depend on a fire to feed themselves, there may well have been a large number of poorer people who ‘chose’ not to burn very much of anything at all.

A seventeenth-century coal seller, captured by Marcellus Laroon for The Cryes of the City of London, Drawne after the Life (c. 1688). The cry ‘Small coals!’ appeared in the very first broadside versions of Cryes of London, dating to the 1620s, suggesting a street trade was well-established by then.

Looking ‘inside’ individual homes is difficult due to the legacy of the Great Fire, which erased a large body of evidence about the lives of ordinary folk. Just as the housing stock went up in smoke, so too did the vast majority of local records. Many other areas of the country boast large collections of wills and inventories describing the possessions and household interiors of the middling and better-off members of sixteenth-century society, but such surviving records are much rarer from within the city. The very wealthy are more likely to have left a trace, probably because their records were considerably more copious in the first place, and because they were often deposited in a variety of locations, sometimes far from the capital.

An interesting slice of life in London in 1620 comes from the household account books of Sir Thomas Puckering, the Member of Parliament whose use of faggots and furze helped us to understand woodland management. Sir Thomas lived in rented accommodation in London for part of the year, spending the rest of his time at his main home in Warwick. Fortuitously, his accounts thus probably rested in Warwick when the fire broke out in Pudding Lane.

On 11 January 1620, Sir Thomas was preparing to move up to his lodgings in London where he was ‘going thither to Parliament’. In anticipation his servants laid in a stock of fuel, purchasing one chaldron of sea coal for 18s and a thousand oak billets for 20s. The following week, after he’d arrived, saw purchases of a handsaw ‘to saw our billets with’ and a sawhorse ‘to saw them on’. There was also a payment of 1s 6d to his bailiff ‘for dressing the wood in my woodyard and carrying it into my woodhouse’. Most of the family and servants had stayed behind in Warwick on this occasion, so the fuel was intended for use by a fairly small group. Yet, both types of fuel were essential to maintaining a gentleman’s London home, and they were both bought in bulk.

One of the earliest London inventories taken by the Court of Orphans (who looked after the inheritances of the underage orphans of freemen of the city and whose records do survive), that of Robert Manne from 1623, did not list the fuel in the house. However, it did allude to fuel choices through the inventory of household equipment, including ‘an Iron for seacoles’ in the kitchen and ‘an iron grate’ in the ‘long garret’. The other fire furniture within the house – and it was a big and richly equipped home – were more suitable for wood-burning. This provides a clue to interpreting the inventory of Gregory Isham’s estate in 1558. Like Manne, Isham was a wealthy London mercer with a large and well-furnished home in the city. (In this case, the family also had a house in the country, where copies of the inventory were preserved.) Here there was a particularly early reference to possible coal-burning consisting of an ‘Irene harthe’ in ‘the garrettes’. The Earl of Rutland’s London pad was much grander than either of these men’s homes. In 1630 alone, the household consumed a colossal volume of fuel: 30 chaldrons of sea coal (equivalent to 42 tonnes), 6 tonnes of a cleaner variety called ‘scotch coal’ (from Scotland), 26 loads of faggots and 12,000 billets.

That the wealthy felt the need to continue the practice of wood-burning is no great surprise. Sea coal was smelly and dirty, a fact of life about which people moaned repeatedly. High-quality firewood and charcoal remained readily available in London, if you could afford it. The rising price, I imagine, might have lent wood fires a sheen of status and exclusivity. But why were they also burning coal? Both mercers appear to have used coal in the lower-status areas of their homes: the kitchen and the garret. Parlours, halls and chambers, which were more likely to be occupied by the master and mistress, were furnished with andirons to support wood within a fireplace. This pattern continued for decades: coal for the kitchen and servants’ areas, wood for the spaces occupied by more ‘important’ household members and their guests.

Each according to degree

That the wealthy aspired to manage households noted for both fine hospitality and frugal housekeeping might seem contradictory. But these aspirations were tightly bound up with the belief in socially appropriate provision, the idea that what was suitable, and indeed necessary, for a lord was not the same as for a labourer. Differentiated provision was a moral good in Britain (and wider Europe), allowing lavish spending on entertainment and economizing in housekeeping to sit comfortably, side-by-side. Indeed, we see this worldview holding in many aspects of British life through to the nineteenth century.

Sixteenth-century British society still followed a legal code for appropriate dress, called the sumptuary laws, which stipulated cloth types, colours and even cuts of clothing according to a person’s social status. The restrictions were laid out most precisely at the upper reaches of society, where the clothes of a duke were distinguished from the clothes of an earl and so on, but even commoners’ dress was prescribed. Apprentices were required to stick to a more restricted range of styles and cloths than those allowed for their masters, in whose homes they lived. This public, visual stratification was seen as a virtue; it helped to produce a ‘well-ordered society’.

Food preparation fulfilled a similar philosophical function and was backed up by contemporary medical understandings. Food suitable for your station in life was considered to be healthy, while food for a different walk of life was wasted on you. Medical men even argued that the digestive processes of labourers and lords worked differently. Labourers were said to have ‘hotter’ stomachs that cooked and broke down coarse fare, turning it into good, digestible ‘chile’. If they ate more dainty meats, it was believed their stomachs would scorch and ruin the food, providing no nutritive value.

Within the wealthier households of the day different dishes were served to people based on their social status. The lord and his fellow diners at the top table enjoyed a large, varied array of dishes, many of which employed great labour on the part of the cooks. Plain, cheap, hearty food was offered to the ‘lower’ servants, while a larger, more mixed menu was laid out for higher-ranking ones. The very top echelons of domestic staff were favoured with a few additional dishes from the lord’s table itself. Since most members of the household, regardless of their status, ate together in the main hall, the different provisions of food were very obvious. They were supposed to be. Social cohesion and hierarchy were understood to be strengthened by the daily ritual of eating together, ‘each according to one’s degree’.

Over time these two aspects of living life ‘according to degree’ fell out of use. Sumptuary laws were no longer enforced, and communal but stratified dining lingered only in university colleges and similar hierarchical institutions. But the general feeling that there was an appropriate level of provision for differing social levels continued into the early twentieth century, particularly in households where servants were clothed in graded uniforms and fed plainer, cheaper food.

The arrival of coal into domestic spaces may well have offered a new arena for performance of the powerful old notion of ‘each according to degree’. William Harrison, in the 1587 edition of his Description of England, wrote with concern about wood shortages and the possibility that people might be forced to burn inferior fuels such as dung, reeds, straw and coal – even in the city of London. Coal was already associated with the poor; the shock to Harrison and his ilk was that this ‘poverty fuel’ was being adopted by other social classes. Yet, at the same time, the initial upsurge in coal supplies may have given wealthier households a new means for upholding the social order. Now that there was a luxury fuel and a lesser, common fuel, it may have seemed morally right to incorporate the difference into the management of their homes.

Returning to Sir Thomas Puckering’s accounts, we find patterns of fuel provisioning that fit with the concept of one fuel for the masters and another for the servants. Among the estate documents that have survived is the inventory of his possessions at his death in 1637, which can be used to paint a picture of his Warwick home and its heating.

Sir Thomas should not have had any trouble fuelling this home entirely with wood if he had chosen to do so. He owned a wood at Weston from which he sold large quantities of faggots, and another area that yielded large quantities of furze. The accounts for building works on his properties suggest he was also able to draw a significant volume of timber from his own land. When summing up his household expenses, he indicated the regular use of fuel grown on his estate with the phrase: ‘Besides all maner of wood, and furzes burnt in my house at Warwick, being of my own growth and not rated.’

Yet wood was not the only fuel in use. From the beginning of May until mid-August, every entry in the section of accounts entitled ‘Weekly expenses in the charge of my house viz in diet, fewell, candles, washing etc’ included ‘pitt-coles’. Not ‘sea coal’, like that which arrived in London from Newcastle via the sea route, but coal from a pit in the Coventry coalfield a few miles distant. Unfortunately, we don’t know which pit the coal came from, so we don’t know exactly how far it had to travel. The amounts varied from half a load up to six ‘lodes’, week to week, for a total of twenty-nine loads over sixteen weeks. Since all but one of the entries included a fraction of a load – measured in halves or quarters – it seems that a load was a recognized unit of sale. From May until August most farmers needed their horses on the land far less than during the rest of the year. So, rather than being a weekly supply of coal, the loads, which were probably conveyed by cart, may represent delivery of the coming year’s stock of coal supplies.

Then, from the end of August through to the beginning of November, Sir Thomas’s estate paid for five substantial deliveries of charcoal. The pit coal cost him around 13½s a load, while bags of charcoal (again, we don’t know how big a bag was) cost him 11d each.

The home where all this fuel was burnt was called ‘The Priory’ and, after the Castle, it was the largest residence in Warwick, with over fifty rooms plus a host of outbuildings. Outside there was ample provision for many different types of fuel. A ‘Coalehouse’ was home to both ‘Seacoales and charcoales’ and featured a weighing beam. More charcoal was housed in the brewhouse; the ‘Woodyard’ contained eight loads of firewood and another weighing beam. Timber was housed in two separate buildings, with another load of wood up at the mill.

Sir Thomas Puckering’s Priory, in Warwick, as it appeared about 1656. Sir Thomas’s household accounts showed wood, charcoal and ‘pit coal’ from a colliery in Coventry, each fuel being used in different areas of the Priory.

The charcoal appears to have been primarily associated with brewing beer, since one entry specifically gave the purpose ‘to drie my hoppes with’. It may have also been used within the house in chambers without chimneys, because it gave off little smoke. But apart from two chafing dishes in the kitchen and the possibility that ‘twoe Iron fire panns’ in the wardrobe were for charcoal, there were no other suitable containers listed.

There may have been charcoal stoves built into the kitchen, and these would not have appeared in an inventory of movable goods. Large-scale boiling and roasting – as would be customary in such an extensive household – would have required large fires, with unimpeded access for turning, stirring, basting and regulating temperature. Having an array of small pots full of sauces and dainty dishes – destined for Sir Thomas’s table – sitting around the edge of these main fires would have been a nuisance and, in my experience, resulted in lots of spills. Many of the surviving kitchens of the era show evidence of having had charcoal-fired built-in stoves. In the brewhouse, using charcoal would of course have ensured the flavour of the brew was not tainted with smoke.

The wardrobe, meanwhile, would have been jam-packed with textiles: bed hangings, coverlets, turkey carpets, tapestries, quilts and curtains. It needed to be kept free of damp and cloth moths. The contents would have been regularly aired and brushed in front of a non-smoky fire, with perhaps a handful of herbs tossed on now and again to fumigate the room. Charcoal was a specialist fuel, worth its expense to the wealthy because of its technical properties. Most of the rooms were equipped with andirons, sometimes termed ‘cobirons’, and one entry in the inventory, for a small room adjoining the nursery, suggests that these were indeed for burning wood, since the space was described as ‘where wood was usually layd for the use of the said chamber’. Fire furniture appropriate for wood-burning was present in sixteen parlours and chambers, while a similar number of rooms appear to have been unheated. Those with wood fires were especially well furnished, with a number of textiles and upholstered chairs – the very latest thing in 1637. These were high-status spaces where Sir Thomas entertained his best guests.

However, two chambers, one occupied by ‘Tobias’ and the other by ‘Mr Brotherton’, as well as a closet used by Sir Thomas himself, had iron grates. So too did the rather empty-sounding ‘Hall’, which had nothing but some tables and benches, a bit of armour on the walls and a grate. The pantry also contained an ‘old’ iron grate, and there was another in the ‘wool house’. The fire furniture within the kitchen would seem inconclusive, comprising of no more than ‘twoe Iron barrs’, if it were not for the presence of a ‘coal hammer’, an instrument used to break up large lumps of coal into more manageable sizes. Why was Sir Thomas willing to spend good money bringing coal into his house when he had such ample wood supplies? Why was coal being used in particular spaces within his home while wood was used in others? Coal was being used at The Priory in seven separate spaces, three of them in service areas – the kitchen, pantry and wool house. It was also used in the hall, a sort of crossover space. Traditionally, the hall would have been the main receiving space for guests, but by 1637 this function had largely faded away. Sir Thomas’s hall, like many halls in wealthy homes, had devolved into little more than an anteroom. It was still somewhere his tenants might come if they had important issues to discuss with their lord, and all guests would enter the house through it. But the best guests would be invited through into one of the more private (wood-burning) parlours, leaving their own servants to wait in the hall (with its iron grate for coal). On a practical note, a coal-burning fire in this largely uninhabited space required very little tending. Indeed, the coal grate in Sir Thomas’s closet may have been set up with this in mind. A closet was a private space, visited by neither guests nor servants. Think of it perhaps as the lord’s version of a ‘man cave’. Sir Thomas kept his books in his, along with three little cabinets, a small table, a stool and ‘an old Cloth Chaire’. A fire that necessitated little attention may well have afforded the seclusion he sought in this space.

Among the elite he was not alone in his fuel choices. The surviving household accounts of the Earl and Countess of Bath cover both their rented London town house and their main country residence, down in Devon. For their Lincoln’s Inn Fields town house, they purchased sea coal, scotch coal, billets and faggots. Payments to the woodmonger featured about four times as often as those for coal, but the quantity of sea coal was still substantial, with a few smaller purchases of scotch coal. Like The Priory, the house in Devon of the Earl and Countess of Bath was very well provided with a variety of wood. Sales of surplus faggots, timber and billets brought in a substantial revenue. Yet almost as soon as the accounts began, in 1637, they were also buying coal. Its usage within the house can be deduced from not one but three inventories taken: one in January 1638, when the old countess, Lady Anne, died; a second in March of the following year, a little before the new countess, Lady Rachel, first visited the house; and a third in 1655, when Henry, the fifth earl, died. In all three, coal appears to have been confined to the service areas of the house.

In Hertfordshire yet another wealthy household was firing its service areas with coal. The House at Gorhambury, near St Albans, rented at that time by Sir Edward Radcliffe, heir to the Earl of Sussex, had twelve chaldrons of sea coal in stock on 1 October 1637. There was an iron grate in the scullery and another in the kitchen, which may or may not have been the same set-up as the ‘kitchen range’ with an iron back that had to be mended twice within the next two years. Much larger stocks of wood of six different types strongly suggest the rest of the house was fuelled by wood.

All three of these households were led by people who spent part of their time in London and part of it upon their country estates. Was it their life as Londoners that got them to seek coal for use out in the country?

Coal copycats

Coal had come to be seen by the wealthy as perfectly appropriate for kitchens and servants. Perhaps some had even begun to think of coal as ‘better’ suited for cooking, particularly in a few important contexts.

For many years, historians have pointed to the uptake of coal by the poor to show that this change came from the bottom up rather than the top down. Indeed, I made this argument myself. One of the most persuasive sources of evidence for this view were the records of how various public and charitable bodies provided coal as a free or cheap fuel to alleviate the hardships of the poor. These of course tell us that some of those living in poverty were being provided with coal – and presumably, using it – but it also tells us that this is what their wealthier neighbours thought was suitable for someone in their predicament. Widespread endorsement by the great and the good of coal as fuel for the poor can only have eased the passage of more coal into the city. It is easy to imagine the odd case where coal was urged upon a resistant and conservative householder in financial difficulties by those who professed to know what was best for them. Certainly those who accepted a position within an almshouse were left with no choice but to take whatever fuel was offered, or enjoy a very cold and bitter winter.

A coal merchant’s trade card, showing heavers unloading coal from a barge on the River Thames (c. 1720–1760). Was the big switch to coal made first by wealthy or poorer households?

But as London’s wealthy families took to using coal in the service areas of their homes, they inadvertently raised the social status of this fuel and provided an arena for the young women (and a few young men) working for them to gain a good deal of experience in the new art of coaxing coal fires into life. Service was not seen in quite such an unremittingly derogatory light as we in the twenty-first century might imagine. Much depended on where you worked and who was your master. The life of a servant in a great house was wholly different to that of one in an inn or tavern, and equally different from that of a lone servant in a craftsman’s home. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, many young people spent a number of years working in someone else’s house before marrying and setting up on their own. Out in the countryside, where much of the work was agricultural rather than purely domestic, as many as 70 per cent of young people did so.

These young servants came from a variety of backgrounds. Those in London were often from outside the city, having grown up as the daughters (or sons) of middling and small-scale country farmers. Others were the children of craftsmen or labourers. Most hoped one day to be mistresses (or masters) themselves, and a minor but significant proportion succeeded. Service was not considered to be for ‘the lowest of the low’; it was an occupation for young people who thought of themselves as of the middling sort. Naturally, youngsters with connections were able to gain the most sought-after positions, generally within the wealthiest households. These young people were most decidedly not ‘poor’. They came from comfortable homes and were paid good wages, clothed well and fed well. Thus, it was a servant elite who were working within the coal-burning service areas in the homes of men like Sir Thomas Puckering. Coal may have begun its rise by being associated with poverty, but by the 1600s it was becoming linked with wealthy kitchens, brewhouses, sculleries, garrets – the world of the elite domestic servant.

These former servants would have been in a good position to bring coal to the wider population. Trained in its use, and perhaps seeing their skill as emblematic of a higher-status profession and class, they were likely advocates for the adoption of coal within their own, more modest homes. A new generation was eager to make the switch to coal. The question now was how to satisfy their demand for it.