Chapter 10

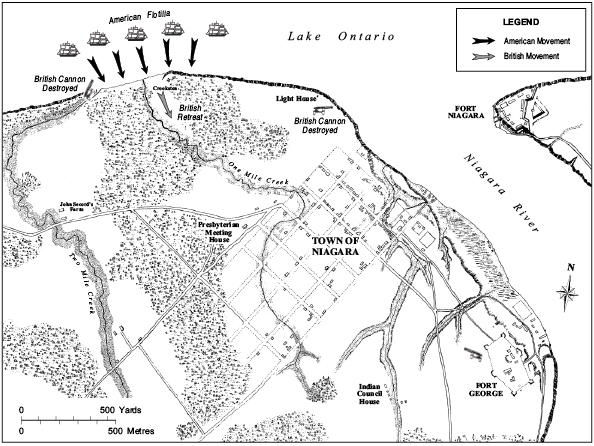

The Battle of Fort George[1]

It must have been a very long night for hundreds of British soldiers and Canadian militiamen lying on their arms in the tall grass out on the Commons. For days everyone knew the Americans were massing a huge invasionary force,[2] and false alarms had already made for many restless nights. Two days earlier Fort George had been subjected to a horrific bombardment from American batteries. By 2:00 p.m. virtually every wooden building and gun deck within the fort had been destroyed.

The town had also sustained collateral damage from the bombardment. Anticipating a major battle most of the townspeople had already packed up their treasured belongings and sought shelter in the township. Four year-old John Carrol later recalled the great excitement within his own household during this period. With “bullets” and cannon balls raining down on their little house, John’s mother hurriedly gathered up the children and some household effects, seeking refuge on an open wheat field where they rested on a blanket. When a cannonball ploughed into the ground nearby they escaped to Four Mile Creek, leaving behind their horses on the “common.” Meanwhile, “the militia men [went] pouring into the house to receive a badge of white cotton or linen on the arm to let the Indians know that [they] were British.”[3]

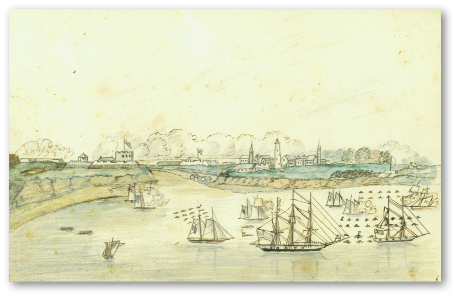

With only a small detachment retained inside the smoldering defenceless fort, the entire garrison had been forced to sleep on the Commons under the stars. Covered in heavy dew, the men were chilled lying in their soaked, heavy wool uniforms. Shortly after a rousing reveille had been sounded by a British bugler, a single rocket was fired above Fort Niagara, followed by a thirty-minute unanswered American cannonade from the fort. Was this the signal that the Americans were finally coming? A thick layer of fog hung over the lake and river obscuring any activity. Occasionally sounds could be heard: the splash of oars, the creaking of ropes, the flap of sails. Finally, several hours past daybreak, the fog banks rolled away revealing a huge armada across the mouth of the river two miles out on the lake — sixteen ships and over one hundred boats and scows each conveying thirty to fifty men.[4] The much-anticipated American invasion had indeed begun on the morning of May 27, 1813.

Capture of Fort George, artist unknown, coloured, engraved aquatint, Philadelphia Port Folio, July 1817, p. 175. This is a naïve view of the American amphibious invasion, May 27, 1813.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #988.259.

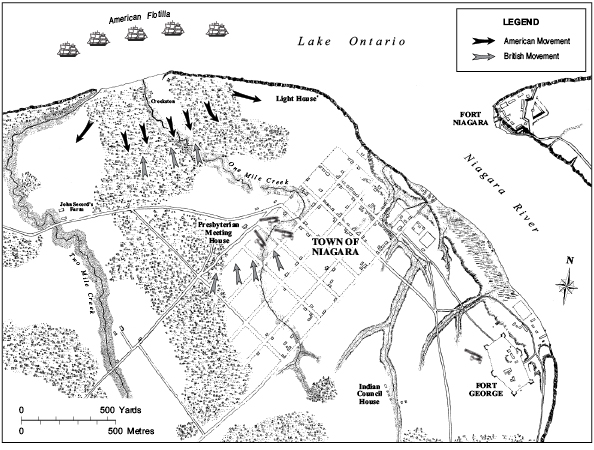

Three armed American schooners quickly took out the one gun at the lighthouse battery. The other one-gun battery along the lakeshore near Two Mile Creek was also disabled. A small piquet of Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, fifty Natives under Chief John Norton, and officers of the Indian Department, stationed at one anticipated landing site near One Mile Creek were subjected to withering offshore cannon fire and were soon forced to withdraw with heavy casualties.[5] At 9:00 a.m., with the firepower of over fifty naval guns firing broadside over their heads, the invaders, under the command of the young aggressive Colonel Winfield Scott, began the assault on the beach near Mr. James Crooks’s house at One Mile Creek.[6] As the Americans ascended the low sandbanks along the shore, they were twice forced back by a small but determined combined force of Glengarries, men of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Lincoln militia including Runchey’s black corps, and soldiers of the 8th Regiment. Eventually, however, 2,300 Americans gained the plains and were faced down by approximately 560 combined British forces. In what is considered one of the fiercest battles of the entire war, “for fifteen minutes the two lines in front, at a distance of from six to ten yards, exchanged a destructive and rapid fire.”[7] With every field officer killed or wounded, the British withdrew, leaving nearly three hundred dead and wounded on the field. Although reinforced by fresh troops and field artillery, the British could only delay the relentless southward advance of the Americans, who had gained another two thousand landed reinforcements and extensive field artillery. The Americans advanced in three columns: their left flank proceeding past the lighthouse and along the river, their right flank proceeding through the woods west of the Two Mile Creek, and the main force cautiously marching through the western section of town[8] with their band playing “Yankee Doodle.”[9] Their advance was temporarily halted at the Presbyterian Meeting House by British field artillery covering the British withdrawal. By 11:00 a.m. the British had re-assembled on the Commons near the Indian Council House, preparing to make a stand. British artillery firing for half an hour from one surviving manned battery near the fort effectively stopped the American advance. However, it became apparent that the American flank companies were moving to cut off any possible British withdrawal. Just before noon, British commander Brigadier General John Vincent reluctantly ordered Colonel William Claus to evacuate Fort George, but not before spiking the guns and exploding the small powder magazines within the fort.[10] Quietly, the British infantry forces retreated through the woods towards St. Davids. Meanwhile the field artillery and some baggage carts withdrew along the River Road towards Queenston and then on to St. Davids, the DeCew House, and eventually Burlington Heights. John Norton and a small band of Natives covered the escape. Surprisingly, the Americans made no serious attempt to follow until June 1. When later chastised for missing this opportunity to capture the British Army, the commanding officer, Major General Henry Dearborn,[11] explained that his men were just too exhausted, having been up since one o’clock in the morning when they had boarded the assault boats. Moreover, not wanting a repeat of the disaster at Fort York one month earlier,[12] the Americans very cautiously approached the “abandoned” fort; inside they found a few soldiers of the 49th trying desperately to cut down the flagstaff in a failed effort to prevent the enemy’s capture of the garrison flag. They also found 124 sick and wounded in the garrison “hospital,”[13] as well as several military wives cowering inside a storage compartment within one of the bastions. Commodore Isaac Chauncey, whose navy had made the amphibious capture of the British Army’s Central Division Headquarters possible, proudly reported, “I am happy to have it in my power to say, that the American flag is flying upon Fort George.”[14]

8th Regiment of Foot, colour illustration of the 1813–1815 uniforms of a private and an officer. At least five companies of the 8th King’s Regiment were present at the Battle of Fort George.

Courtesy of René Chartrand, from Historical Record of the King’s Liverpool Regiment of Foot (London: 1883).

Undoubtedly there were many acts of heroism performed that day. One enduring story relates to Dominick Henry, the keeper of the lighthouse at Mississauga Point. Amidst the carnage of all the bombardments from the ships and Fort Niagara, Henry (a retired Royal Artillery officer) bravely assisted the wounded while his wife provided refreshments to the troops.[15]

Besides losing the fort with most of its ordnance, supplies, and soldiers’ baggage,[16] Brigadier General Vincent reported over 350 regulars killed, wounded, or missing. Five officers and eighty men were killed or missing in the Lincoln Militia. At least two Natives had been killed, as well as officers of the Indian Department. The Glengarries lost seventy-seven men of 108 deployed. Many of the British killed were buried in unmarked graves on site. The official total loss for the Americans was 150 killed or wounded.[17] The only American officer to perish was Henry Dearborn’s grandson, Lieutenant Henry Hobart.[18]

The American flag would cast its long shadow of occupation over Fort George, the town and the Commons for the next seven months.

One hundred and seventy years later, seven teenagers were “hanging out” on the Commons having a beer or two. As they relaxed in the tall grass, suddenly “a blue-coated soldier ran by them his back on fire.”[19] After a long pause, one of the boys questioned whether anyone else had just witnessed something strange; each of the seven had seen the same thing. A search of the area failed to find any trace of the poor fellow. Some believe this was the spirit of a British artillery officer who had stayed in the fort as it was consumed by fire from American bombardment; others surmise the apparition may have been an American infantryman who had torched the town.