Chapter 11

The New Butler’s Barracks Complex

There has long been confusion among historians and locals about the Butler’s Rangers’ Barracks built in the winter of 1778 overlooking the Niagara River and the preserved Butler’s Barracks buildings situated on the western edge of the Commons today. At least one historian claims that a small Butler’s Rangers’ Barracks was indeed present at the modern site in the late eighteenth century, but thus far there is no credible documented evidence. According to Mrs. Simcoe’s diary, upon arrival in 1792 the Queen’s Rangers encamped “within half a mile”[1] behind Navy Hall, but no permanent building would have been erected as they soon were dispatched to Queenston where they established a more permanent encampment. Quite clearly the surviving buildings of the Butler’s Barracks complex do not predate 1814. With the final destruction/decay of the original Rangers’ Barracks during the War of 1812, the name was probably given to the new military complex in recognition of the noteworthy military leadership of John Butler during the American Revolutionary War.

Early in the War of 1812 it became painfully obvious that Fort George and Navy Hall could not withstand the horrific bombardments from the American batteries both at Fort Niagara and directly across the river. By early 1814 the Royal Engineers were ordered to relocate many of the storage facilities to the western edge of the Military Reserve, which, although possibly still within range of American guns, would at least be out of sight of American artillery officers. It appears the new Butler’s Barracks complex grew initially in an unplanned and haphazard manner as a cluster of buildings on the open plain. By 1817 there were already a dozen buildings onsite, including log barracks, dwellings, storehouses, a hospital, and outbuildings. Only the Commissariat Officer’s dwelling house has survived from this early period.

The Butler’s Barracks complex had two primary functions. The first was to provide storage, or “stores,” for all the military installations in the Niagara Peninsula. The second purpose was to provide the living quarters for most of the British garrison at Niagara. (Fort Mississauga, which was not completed until 1826, housed the Royal Artillery defending the mouth of the Niagara River; the decaying barracks of Fort George were no longer fit for British regiments; Navy Hall, although primarily a storage depot, at times was converted into temporary barracks.) The types of buildings at Butler’s Barracks reflect the multiple functions of the site: the commissariat officers’ quarters, the commissariat stores and offices and for the regular army, officers’ quarters and mess, barrack master’s house, single and two-storey barracks, gun sheds, and Dragoons’ stables.

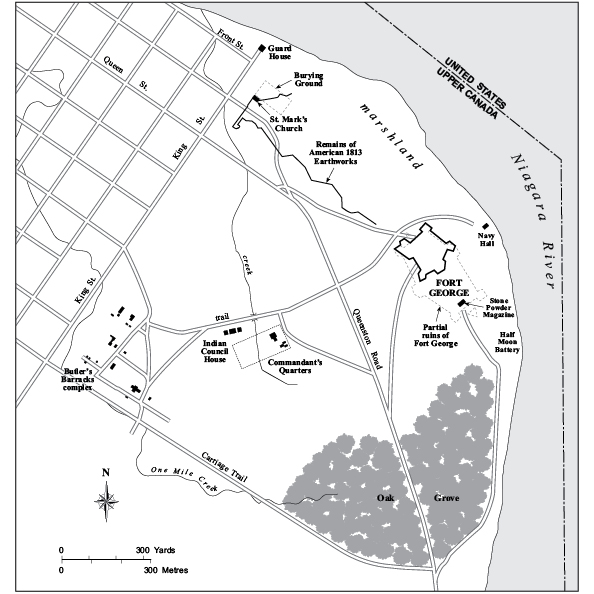

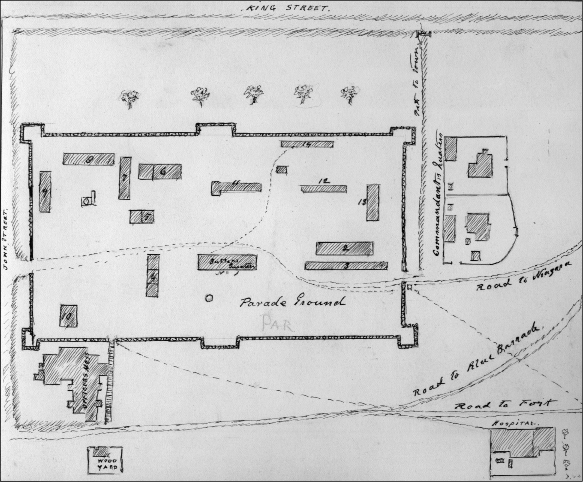

Fort George Military Reserve/Commons, 1817. By 1817 Fort George was already deteriorating. A new Indian Council House and a commandant’s quarters were built in the middle of the Commons. Several new buildings were established in the Butler’s Barracks Complex.

On reading the many reports for the various buildings at Butler’s Barracks, one quickly concludes that most of the buildings were built in haste with inadequate foundations, using unseasoned timber and wood. Most of the buildings underwent many repairs and revisions, and the function of individual buildings was frequently altered.

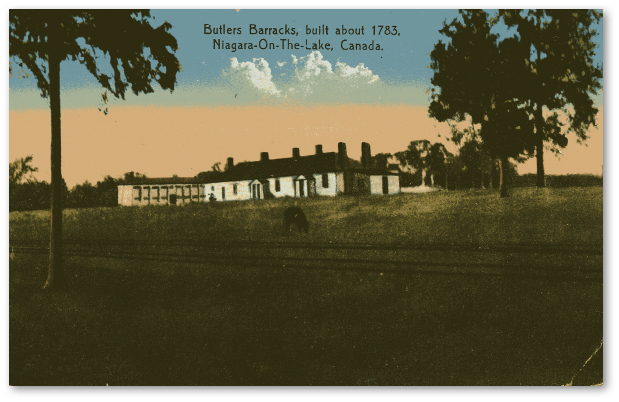

Butler’s Barracks, postcard, circa 1910. In the foreground is the officers’ quarters and mess with the two-storey barracks behind. Note the grazing animal and the two sets of tracks of the railroad spur line along John Street East.

Courtesy of the author.

One historian noted that the organization of the British Army in the eighteenth [and nineteenth] century was “weird and wonderful.”[2] The British military establishment consisted of many departments with varying and often overlapping functions and responsibilities. As another historian points out:

In order to support a fighting soldier in the field, the army required a broad range of services including food supplies, adequate living quarters, camp equipment clothing and the armaments of war.[3]

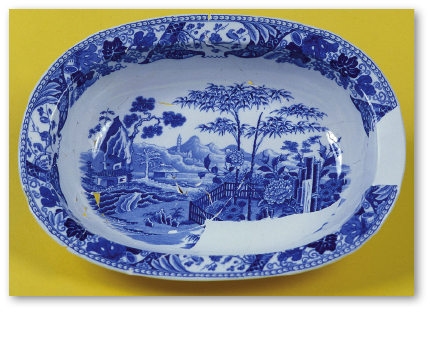

Vegetable dish, photo, George Vandervlugt. Obverse decorated in “Chinese Garden” pattern by Wedgwood. This dish was found during the 1978 archaeological excavations at the 1816 officers’ quarters and mess.

Courtesy of Parks Canada, #RAO2P.

Vegetable dish, photo, George Vandervlugt. Reverse, insignia of the 70th Regiment, which was stationed at Fort George April–June 1817.

Courtesy of Parks Canada, #RAO1P.

To meet these requirements the military bureaucracy was often stifling and contentious. For example, the Board of Ordnance, responsible for all military lands and buildings in Canada, supervised the actual construction of the barracks through the Royal Engineers on site. The quartermaster assigned the barracks space within the fort, but the barrack master outfitted the barracks according to strict regulations. The commissariat officer had to tender and purchase the supplies for the barracks, but the storage of those supplies was the responsibility of the storekeeper.

Weapons and ammunition were the purview of the Ordnance Board; it was the responsibility of the Commissariat Department to tender and purchase all other supplies for the army, including the inspection and procurement of all food supplies, fodder for the animals, and fuel. The commissariat officers were administrative rather than military personnel and answered to the Lord Commissioners of the Treasury. Although these civilian officers did not hold the king’s commissions, they were issued quasi-military uniforms.[4] To ensure security and efficiency, their offices and residences were usually on the edge of the military complex, but they were readily accessible to the local suppliers as well.

Board of Ordnance stone marker, 2012. The Board of Ordnance was responsible for all military lands and buildings in Upper Canada. Such markers inscribed with BO and the broad arrow were used to identify military buildings and the boundaries of the Military Reserve. This marker has probably stood sentinel in front of the Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters since circa 1816.

Courtesy of the author.

1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards Marching Order, artist M.A. Hayes, lithograph by Spooner, 1840.

Courtesy Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library.

Most military garrisons enjoyed expansive boom years, alternating with stagnant periods of benign neglect with the ever present fear of closure of the site altogether. In the decades after the War of 1812, the Niagara installations were subject to these same fluctuations. On several occasions the threat of closure nearly proved disastrous to the integrity of the Commons as we know it today. In the early 1830s, burdened by the high costs of maintaining their world-wide empire, the British government decided to withdraw its regular troops from Upper Canada’s frontier posts. The buildings and adjoining lands at the Niagara sites were divided into lots and advertised for rent,[5] but subject to cancellation should a military crisis arise. The surprising outbreak of the rebellion of 1837 and the establishment of William Lyon Mackenzie’s provisional republican government on Navy Island in the upper Niagara River quickly brought such plans to a halt, with the government rushing fresh troops and arms to the much agitated Niagara frontier. One British regiment assigned to Niagara was a detachment of the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards, arguably the most handsome regiment ever to march or ride across the Military Reserve. One local resident recalled:

perhaps the finest military body that ever came to the district, the King’s Dragoon Guards’ officered by men of wealth and title. The men were all six feet in height with fine well trained horses. Butler’s Barracks was put in order for them, many of the officers were in private houses. Some of the young officers when on a lark often carried off the big gilded boot of P. Flinn, shoemaker, and sometimes paid a fine of $25 for this, so that it proved very profitable to the owner.[6]

The troop arrived in Niagara in mid-1838, creating quite a sensation among the women of the town and also reluctant admiration from the men. During their stay, the officers of the regiment were active members of various social clubs in town, including the prestigious Niagara Sleigh Club. No doubt there were amorous liaisons with local belles. In August 1842 Sergeant John Morgan of the King’s, by then stationed in Chambly, Lower Canada (now Quebec), was granted a one month furlough (which was later extended) to return to Niagara.[7] We may never know why this furlough was granted, but we can surmise that he had left a loved one behind, perhaps a love child, or perhaps he simply had an old score to settle.

Dress Helmet, Non-commissioned Officer, 1st King’s Dragoon Guards, ornate beaten brass, circa 1838. Large plume illustrated in previous print is missing.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum #972.917.1.

To meet the needs of the elite dragoons the barracks were refurbished and the officers’ quarters renovated; special stables were erected for the cavalry horses, as were veterinary stables, a forge, and a saddler store. Responding to the heightened military activity at Niagara and need for increased stores, construction began on the two-and-a-half-storey commissariat store and office in 1839. In the same year the Royal Engineers constructed a rectangular defensible picket stockade with mock bastion corners and two gates around the twenty-acre complex. Interestingly, the officers’ quarters and mess, the barracks officer’s quarters, the barrack master’s quarters, the Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters, and the military hospital were all left outside the fortifications. At its peak there were over thirty buildings or structures in the complex. Later, responding to complaints that during certain seasons access to the hospital was almost impassable due to mud and water, a plank walkway 1,218 feet in length was laid down between the front door of the military hospital in the middle of the Commons to the two-storey soldiers’ barracks inside the stockade.

Much to the locals’ disappointment, the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards were withdrawn to Lower Canada in July 1841, and for two years all was depressingly quiet at Butler’s Barracks. However, in March 1843, a company of the newly formed Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment (RCRR) established its headquarters at Niagara (a second company settled there later). This regiment was raised to guard border posts and consisted of long service volunteers of good conduct raised from other line regiments serving in Canada. Upon arrival the new commanding officer insisted that the Commandant’s Quarters out on the Commons be completely refurbished.[8] For the next thirteen years the RCRR became an integral part of the community. Many of the officers and some of the enlisted men lived in town with their families. Military tattoos, band concerts, and picnics encouraged the military and civilians to mingle. Many of the men later returned to Niagara to retire.

However, by the late 1840s the colonial office was once again trying to reduce the costs of defending its far-flung colonies. The colonial secretary, Earl Grey, devised a plan whereby the regulars would be withdrawn but retired soldiers and pensioners would perform garrison duty in return, for which they would be granted small two- to three-acre plots of “surplus lands” on the Military Reserve. Here they could erect a dwelling and cultivate their holdings. In the event of a crisis they could quickly respond until regular troops could be rushed in. Although this “Enrolled Pensioner Scheme”[9] was actually attempted elsewhere, it fortunately never gained traction in Niagara, partly due to resistance from local inhabitants who did not want to lose their “common.”[10] Moreover, by 1858 the British government transferred jurisdiction of the military lands to the Crown Lands department of the provincial government, but still with the stipulation of military readiness. A preliminary report to the province by Ordnance Lands Agent William Coffin recommended the buildings of the Butler’s Barracks complex be converted into “a Deaf and Dumb and Blind Asylum for Upper Canada”[11] while the nearby Commons be divided into “convenient farming lots and let on lease for five or seven years.”[12] But Coffin seems to have had second thoughts, for in a later report he appeals for restraint[13] : “The government does not possess in Canada a more beautiful piece of land than the Ordnance Reserve at Niagara or one better suited to purposes of drill and militia instruction.” He also railed against the Erie and Niagara Railway Company for cutting a disfiguring slice across the oak forest (later known as Paradise Grove) on the edge of the Commons.[14]

When the remaining detachment of the RCRR was withdrawn from Butlers’ Barracks in 1858, the provincial government attempted to rent out the buildings once again, always with the proviso that the properties could be taken back for military emergencies. Various uses for the buildings and adjacent lands were proposed. Plans were drawn up to convert “No 6 Cavalry Stables as a school room for 84 scholars,”[15] apparently to accommodate the growing population of children in Niagara. This plan never materialized. William Kirby,[16] who was paid a salary of $1 per day as live-in caretaker[17] of the Reserve, suggested the Commons be converted into a “pleasure ground to attract tourists and encourage games and other sporting events.”[18]

Unease along the Canadian-American border during the American Civil War and the subsequent Fenian Raids in the 1860s once again brought the RCRR back to the Military Reserve, but because of rental agreements some of the buildings were not available for the troops when needed. This seems to have been the last straw and further attempts at renting with “the proviso” for the military ended. Moreover, with Confederation achieved, the new government of Canada decided to retain the Military Reserve at Niagara for defensive military purposes, and no consideration would be given to selling off this “most beautiful piece of land”[19] (at least for another forty years). The buildings of the Butler’s Barracks complex would form the nucleus for the summer militia training at Camp Niagara for the next ninety-nine years.

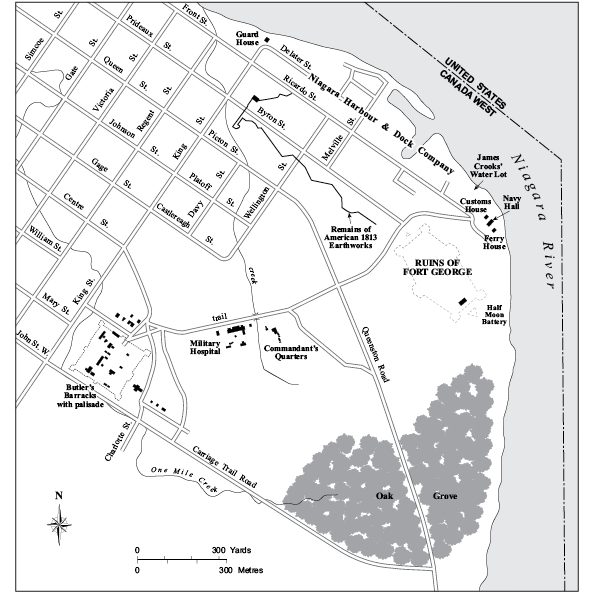

Fort George Military Reserve/Commons, 1850. By 1850 the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company was working at full capacity on its waterfront properties on Ricardo Street. James Crooks was slowly developing his properties southeast of King Street that he had acquired in the great swap. The hospital on the Commons was serving both the military and civilian population. Part of Butler’s Barracks was enclosed within a palisade.

Plan of Butler’s Barracks, pen and ink on linen, circa 1855. Many of the buildings of Butler’s Barracks were enclosed within a palisade.

Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, T13470.

Illustrations for Plan of Butler’s Barracks, pen and ink, circa 1855. Buildings 1, 2, and 3 are still standing today.

Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, T 13468.

Survivors

Only four of the original buildings of the Butler’s Barracks complex have survived into the twenty-first century.

Junior Commissariat Officers’ Quarters

The Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters is the oldest surviving building of the Butler’s Barracks complex, having been built as early as 1814, possibly using materials salvaged from earlier buildings. It apparently began life as a stable, but on the commissariat’s insistence, plans were altered to transform it into a residence.[20] The building was of frame construction with brick infill between the timbers. It was a simple one-and-a-half-storey cottage on a stone foundation with four rooms on the ground floor and a dividing hallway down the middle. There were two sets of back-to-back interior fireplaces. The upper space was unfinished. A separate cookhouse and servants’ quarters were built to the rear of the residence. A well and root house were probably constructed at the same time. A second residence to accommodate another commissariat officer was erected to the north. It soon became the barrack master’s house, but never received the same attention as its neighbour though both shared the same enclosure. Within five years the Commissariat officer in residence requested approval to add a porch at the front as well as a porch at the rear to connect the main house with the cookhouse, various “sundry repairs,”[21] and a fence around the perimeter. When the British troops were withdrawn from Niagara in 1836 the quarters were abandoned, but underwent extensive repairs after the British Army returned in response to Mackenzie’s Rebellion. An enclosed stairway to the attic was completed with several rooms upstairs partitioned and plastered. The stable and coach house were also refurbished. Within ten years it was recommended that the ceiling of the first floor be raised to add height to the ground floors apparently to overcome dampness attributed to the main floor being so close to the outside ground level.[22]

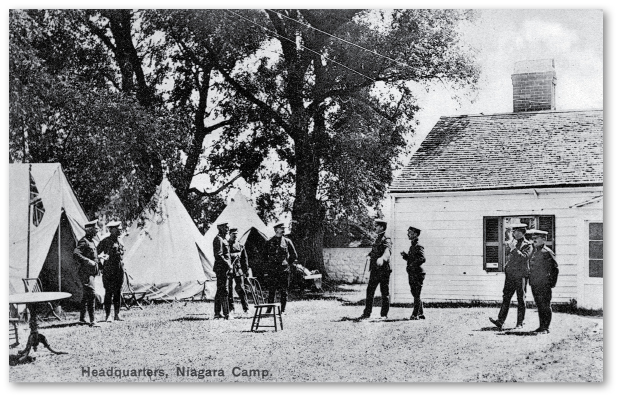

Over the next twenty years, occupancy of the quarters alternated between military personnel during periods of heightened military readiness and civilian tenants. Not only did the latter provide a little revenue for the government but it was generally felt that occupied buildings would be better maintained and less likely to be vandalized. In May 1867 the aforementioned William Kirby moved into the recently repaired quarters as resident caretaker of the Military Reserve. Three years later Kirby had to vacate the quarters, which was turned into the commandant’s quarters for the summer militia camps (see chapter 13). Over the next forty years the two buildings were used during summer camps as the commandant’s quarters, headquarters, or officers’ mess. Here the military elite and politicians of the day were entertained in high style. During the late nineteenth century the building also served as the clubhouse for the Fort George eighteen-hole golf course (see chapter 20) before reverting back to the military just prior to the Great War. The two old buildings were appropriated by the military for the headquarters’ staff and renovations carried out. Together, these were now officially known as “the compound” until the end of the Second World War.

After the Second World War the surplus buildings at Camp Niagara were turned over to the War Assets Corporation for disposal. The Niagara Town and Township Recreational Council purchased from the Federal government fourteen acres of the Reserve, which included the two buildings of the compound. The old barrack master’s house unfortunately was quickly demolished. The former Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters, however, was used by various young peoples groups. Boys’ Town, with its motto “Busy as a Bee,” sponsored regular activities for teens, including boxing, crafts, and floor hockey. Teen Town held Saturday night dances in the old quarters in the 1940s and ’50s.[23] The Girl Guides and Brownies also used the building. The Council also signed a lease for the nominal sum of one dollar per year on a twenty-year term, for the other three surviving buildings of the Butlers’ Barracks complex. In 1952 with resumption of the summer camps primarily because of the Korean War, the government cancelled the sale and leases. Finally, in 1966, with the summer camps at Camp Niagara declared surplus to the needs of the armed forces, the Department of National Defence transferred the property to the National Park Branch (Parks Canada). The latter stabilized the building in the 1980s.

Today, within earshot of a children’s playground, modern baseball diamonds, soccer fields, tennis courts, and the public swimming pool, the old quarters sits quietly nestled amongst mature trees partially hidden behind its tall fence. Many of those passing by on “Brock Road,” walking their dogs, jogging or cycling, are unaware of this little building’s extraordinarily rich history. Yet for all its varied uses the interior retains much of its original fabric and layout. In 2011 Parks Canada in consultation with local heritage groups sponsored another in-depth study of the property. Given its unique cultural heritage and key landscape features it is hoped that a sympathetic adaptive reuse of the property can be found soon. Time is running out for the Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters — possibly the oldest surviving military dwelling in Ontario.

Headquarters, Niagara Camp, postcard, circa 1910. Together the former Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters and the barrack master’s house were known variously as the commandant’s quarters, headquarters, and officers’ mess, and later the compound.

Courtesy of the author.

Soldiers’ Barracks

The two-storey hip-roofed soldiers’ barracks was constructed in 1817 or 1818. The lower wall is composed of horizontal logs while the upper walls were originally frame but later filled with bricks to make the building more splinter proof against rifle fire. The exterior walls are now sheathed in clapboard. The interior of the two floors is identical: two large rooms flanking a central hall. The second floor is accessible only by an enclosed exterior stairs. The barracks could accommodate one hundred men, but for most of its life it was used simply for storage. For nearly two hundred years this building has dominated the Butler’s Barracks complex by its sheer size. Being of log construction it has often been confused with the original 1778 Butler’s Rangers’ Barracks that were built near the Niagara River. The ground floor of the soldiers’ barracks today is the museum of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment which traces its origins to Butler’s Rangers. The second floor holds the regiment’s archives.

The two-storey soldiers’ barracks (1817), photo, Cosmo Condina, 2011. Today the two-storey soldiers’ barracks is the home of the Lincoln and Welland Regimental Museum.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Ordnance Gun Shed

The ordnance gun shed was constructed circa 1821. An early description portrays a clapboarded, wooden frame building, one storey high, built on a stone foundation, with a ramp extending along the entire thirty-three yard front of the building, which is divided into seven bays. Built to store heavy ordnance it was later used as a barracks and storage facility. The building has been restored and is now used for storage by Parks Canada and the Lincoln & Welland Regiment.

The Commissariat Store and Office

The commissariat store and office was constructed during the frantic military build-up of the complex in the late 1830s. This impressive two-and-a-half-storey frame structure also had a full basement. In order to hoist up the heavy crates and containers of stores, a windlass or crane consisting of a huge wheel, eight feet in diameter, with ropes and hooks was installed on the top floor. Several years after the building was completed a huge brick money vault with eighteen-inch thick walls was installed on the first floor. Large sums of money passed through the commissariat department. Today this interesting building has retained much of its original fabric and continues its original use as yet another storage facility.

Today, facing the old parade ground, the soldiers’ barracks, gun shed, and commissariat store sit silently in their government-issue grey paint as mute testimony to the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who have passed this way.

A Notable Non-Survivor

In 1815 the Canadian Fencibles[24] garrisoning Niagara were still using the Count de Puisaye’s house[25] on the River Road as their hospital. Being three miles out of town it was inconvenient for the surgeon’s daily visits.[26] The Fencibles requested a new hospital in the Butler’s Barracks complex, but only a recently built stable was available. With great reluctance and a promise that a new purpose-built hospital would be forthcoming, the modified stable was accepted as a temporary hospital. In addition to a leaking roof it soon became apparent that it was situated in a very unsuitable location in the southwest corner of the Military Reserve. One officer noted:

The Hospital is also situated near to an extensive Swamp, and the Miasmata arising in the summer months from the decay of a luxuriant profusion of vegetable matter (combined with other causes) is sufficient in my opinion to warrant the conclusion that these are the causes of the varieties of remittent and Intermittent Fevers, which I am informed are occasionally prevalent.[27]

It is a swampy portion of One Mile Creek to this day.

Surgeon James Reid of the 68th Regiment was apparently the first to suggest that the soon-to-be-empty Indian Council House buildings could be converted into a hospital.[28] Responding to his request, extensive renovations were carried out with the laying of new foundations and joining the three original buildings together, which resulted in quite a handsome building looking out over the Commons. A plan of the building[29] illustrates “the left wing of the structure was self-contained, and included the surgeon’s quarters, his kitchen and medical storeroom.” The centre and right sections were the hospital proper, including the wards, surgery, kitchen, and the hospital sergeant’s room. “The interior included a long room with a large fireplace, with fine woodwork and carving.”[30] Apparently the building was well maintained, for in 1836 it was described as “[o]ne of the best hospitals in the command.”[31]

Again with the excitement of Mackenzie’s rebellion and the resultant return of troops to Butler’s Barracks the hospital was upgraded. A frame one-storey building measuring twenty-four feet by fourteen feet was erected just to the west of the hospital. One half served as a guardroom complete with bed and an arms’ rack for four muskets. On the other side of a thin partition was the “deadhouse” (morgue). Many a sentry probably had stories to tell about guard duty at the hospital. New stables and a new privy at the rear to replace the former privy situated near the hospital’s front entrance were also completed. The entire hospital complex was surrounded by a close-pale fence. By 1864 the hospital was also being primarily used as a civilian hospital for the townspeople, and hence the recommendation for “one ward at least for women.”[32]

With the British Army relinquishing control of the Fort George complex upon Confederation, the building continued to serve both as civilian hospital for the town and military hospital during the summer militia encampments. However, in February 1882 this old building burned to the ground. According to local historian Janet Carnochan, the foundation stones were “harvested by an enterprising local resident.”[33] In the early twentieth century the Niagara Historical Society erected a commemorative stone cairn.[34] After years of standing forlornly and almost forgotten in the tall prairie grasses it has only recently been recognized as one of the commemorative sites on Parks Canada’s “Spirit, Combat, and Lore: A Walk to Remember” trail. If one stands nearby with the wind blowing you may be able to conjure up blood-curdling Native war-whoops, the screams of terrified patients subjected to surgery without anaesthetic, or the frightened wails of poor souls dying from various afflictions that are readily preventable today.

Queen’s Own Rifles, photo, circa 1865. This is the earliest known photo of the military hospital, readily discernible in the background. The central portion of the building was originally the post-war Indian Council House. Note the deteriorating palisade of Butler’s Barracks Complex and the dog, mascot or stray, in front of the formation.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society #984.201.