Chapter 14

The Great War and Camp Niagara

The summer of 1914 started out like so many previous Niagara-on-the-Lake summers: the militia brigades were back at Camp Niagara; the wealthy Americans had returned to their expansive summer homes; the Queen’s Royal Hotel was full; the steamships and railway were busy bringing in more tourists; tennis, golf, lawn bowling, and yachting were in full swing; the fruit was ripening in the township’s orchards; and the old town’s year-round citizens were enjoying long, languid evenings on their verandas. Canada had just completed a century of relative peace, but on August 5 the daily newspapers reported that Great Britain had declared war on Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With Canada following suit within twenty-four hours, Camp Niagara and the sleepy little town of Niagara-on-the-Lake suddenly became an integral part of Canada’s war effort. Of the 619,000 Canadian troops who fought in Europe, one in ten did not return home. Of the sixty thousand who made the supreme sacrifice during the Great War, a significant proportion trained at Camp Niagara.[1]

Five years earlier at the Imperial Defence Conference in London an agreement had been reached whereby in the event ofwe al war, all military forces within the British Empire would be harmonized into a single fighting force under British command. As a result, Canada’s military lost much of its independence and regimental uniqueness. Moreover, the British military hierarchy, which clearly differentiated between officers and the “other ranks,” was further reinforced. Hence while the officers would continue to wear the comfortable open-necked tunics with ties, the “other ranks” were required to wear the uncomfortable uniforms introduced a decade earlier: the tight tunics of drab rough khaki serge with rigid, high collars that buttoned up to the neck causing chafing and even open ulcers[2]; collarless grey shirts; trousers also of the khaki serge that irritated the skin, especially when perspiring; and woolen undergarments. The men’s legs were wrapped from ankles to the knees in a bandage-like material called “putties.” Although difficult to apply properly and hot during the summer, the water-resistant putties did offer some protection in the wet muddy trenches of France. Brown leather boots and peaked caps decorated with a bronze maple leaf completed the uniform. While in training the men often wore casual civilian clothes topped up by the same straw hats, cocked on one side, which had been issued to the militia ten years earlier and which the men referred to as “cow’s breakfast.” The men were often issued their official uniforms at Camp Niagara just before embarking.

The energetic and opinionated Minister of the Militia and Defence Colonel Sam Hughes directed much of the Canadian war effort. He insisted that the troops use the Canadian designed and manufactured Ross rifle. Although effective if kept clean and not fired too rapidly, in the trenches of France the Ross would easily jam. Occasionally the bayonet would drop off while firing. Frustrated, the men at the Front were always on the lookout for abandoned, more reliable, and slightly shorter Lee-Enfields. Early in the war, Hughes dismissed Camp Niagara as just too small for an effective training camp[3] and directed resources towards the creation of a huge new camp at Valcartier, Quebec. Despite these early threats of closure, tens of thousands of soldiers received their basic training at Camp Niagara.

Soldier “Frank,” photo postcard (damaged), circa 1915. Trainees could have their photograph taken in their new uniform before being shipped out. Note the “Camp Niagara” backdrop.

Courtesy of the author.

Another Hughes initiative was a government call to arms in which all the original named and numbered militia infantry regiments with their strong traditions and esprit de corps were forced to reassign their men to new numbered “Overseas Battalions” of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF).[4] Hence, the locally raised 19th Lincoln Regiment and the 44th Lincoln and Welland Regiments did not fight as separate units but instead contributed men to the various numbered battalions of the CEF. Over the course of the war several other numbered battalions were raised in the Niagara Peninsula. (Three outstanding battalions with a local connection were 81st, 98th, and 176th.)

Within a few days of its declaration of war, the Canadian government raised the First Division of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. This consisted primarily of trained volunteers from various militia and permanent regiments. They quickly assembled at the yet uncompleted Valcartier Camp, were formed into battalions, and along with a cavalry brigade were shipped out to England shortly thereafter. Camp Niagara became the training camp for the Second Division, receiving recruits from mostly southern and central Ontario battalions for eventual service in Europe.[5]

The recruiting offices were initially inundated with volunteers anxious to be part of the war effort; after all, almost everyone predicted that the war would be over by Christmas. And who were these recruits? Many were young men looking for adventure, some were anxious to escape the boredom of the family farm, some enlisted with boyhood chums or felt compelled to volunteer when a friend or family member had been killed. Many were underage.

Most of the battalions arrived at Camp Niagara by steamship from Toronto. Upon arrival the men would regroup on the dock and then march up to camp, usually led by their regimental band. Many were encouraged by the sight of so many young local girls lining the streets welcoming them to town. Unfortunately, with the exception of carefully chaperoned dances, these young ladies seemed to just disappear until they once more lined the parade route as the men marched back down to the docks to embark for Europe several weeks later.[6] Many of the men arrived in civvies; some had inadequate if any boots or shoes. It could take some time before they were fitted for their khaki uniforms and boots and issued kit.

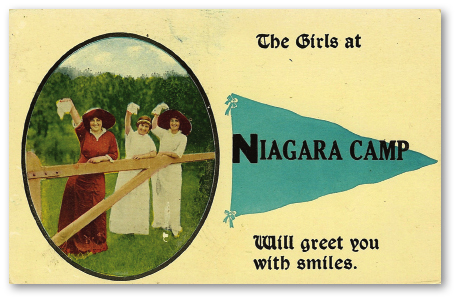

The Girls at Niagara Camp, postcard, circa 1915. Not the postcard a soldier would likely send home to Mother.

Judith Sayers Collection.

With the exception of the Polish army, Camp Niagara during the Great War operated from spring through fall; hence, the camp was “under canvas.” Long rows of canvas tents were pitched on most of the Commons west of present Queen’s Parade. For the “other ranks,” under canvas meant up to nine men with their guns and other equipment sleeping in a small bell tent, feet towards the centre pole with a ground sheet, straw palisses,[7] and, if lucky, three blankets. In the morning “each man’s kit was piled neatly, in geometrically precise lines in front of his own tent. The side walls of the tent were rolled up to provide ventilation.”[8] With the men away on duty, a sentry was assigned to patrol the lines. There were occasional stray animals in camp; sometimes dogs or even goats were adopted as mascots. The 76th Battalion had a black bear as a mascot[9] — an interesting throw-back to a century earlier when the 49th apparently had bears as mascots in Fort George just prior to the War of 1812. The higher the rank, the fewer men per tent, and there would probably be a wooden floor with mattress. Even the camp commandant slept in a tent in the compound of camp headquarters, the former Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters. However, some of the officers of battalions encamped on the Mississauga Commons stayed at the nearby Oban Inn.[10]

A daily rhythm soon emerged for the infantry batallions. Reveille was sounded by the camp bugler at 5:30 a.m., followed shortly thereafter by the regimental bugler sounding a few bars of the battalion’s song, followed by more reveille. For Scottish regiments, a piper sounded the calls. After roll call at 6:00 a.m. it was time to wash and shave outdoors with cold water, dress, put the tent in order, and exercise, all before breakfast at seven. One hour later everyone fell in for duties. After dinner at twelve it was time for parade and more drills until just before supper at 6:00 p.m. Evenings were usually free until roll call at 9:30 p.m., in bed by ten, and lights out fifteen minutes later. Each of these milestones in the daily schedule was announced by a different bugle call[11] — no need for timepieces.

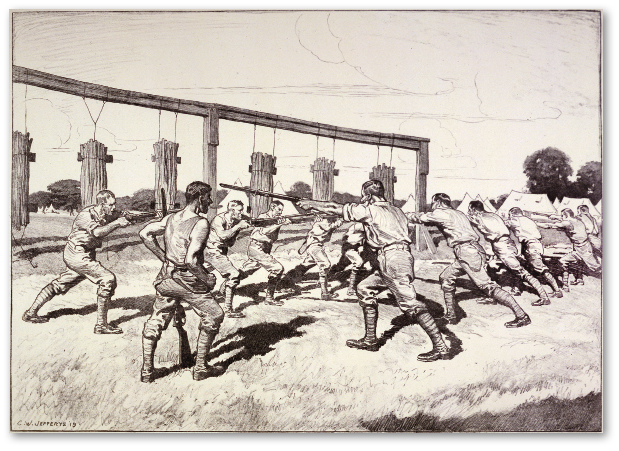

For the infantry, most of their days were occupied by physical training, endless foot drills, lectures, and hands-on instruction with various armaments. Although they were introduced to the newly developed hand grenade, they still spent considerable time on the intricacies of bayoneting straw dummies with “blood curdling yells.”[12] In anticipation of the type of warfare the men would be subjected to in France, great attention was made to trenches. Situated near the river on the edge of Paradise Grove were “first line trenches with barbed wire entanglements and steps and pegs for assisting in charges, trenches with dugouts and look outs, connecting by underground passages with other trenches built with ramparts of sand bags and zigzag to prevent damage from enfilading fire.”[13] Although some live ammunition was used,[14] these simulated trenches on the idyllic Commons could never prepare the men for the horrific mayhem into which they would be immersed on the Front, where if not soon killed or maimed, were often subjected to debilitating shell-shock long afterwards.[15] After the war the trenches on the Fort George Commons were bulldozed over, leaving no evidence of them today. However, there were also trenches dug on the Mississauga Commons, and although they were to be all filled in[16] there is evidence of a least one trench on the golf course near the sixth green.

Parades were an important element of life in Camp Niagara and the town. There were the marching parades on Mary Street to the firing range on the Lakeshore Road, usually accompanied by a band. It was common for the locals to come out and watch the young soldiers march by, with young boys and dogs often running excitedly alongside. There were the “bathing parades”; since there was no running hot water in camp the men were marched to the lake at the end of Queen Street from May to October. Lake Ontario is cold even in August, so swimming in the nude must have been a very chilling experience. On Sundays there were “church parades” to the various established churches in town or on occasion to a large open-air service on the Commons. At these drumhead services the men formed a hollow square (U shaped fashion) with regimental drums stacked at the open end to form an altar. Several chaplains would conduct the service and regimental bands would provide the music. “Onward Christian Soldiers” was a favourite.[17] Any trainee feeling really unwell would be marched over on “sick parade” to the hospital where the genuinely sick would be sorted out from the slackers.[18] Every Friday there was a “route march” to Queenston Heights, a distance of approximately ten miles with a two-hour rest on the Heights before marching home.

The full-scale march could involve as many as ten thousand men each carrying their weapons and sixty- to seventy-pound packs. Individual battalions would march with a proper distance in between with “scouts on the side and in vanguard ahead, climbing fences and crawling under brush to ferret out any ‘enemy’ that might be near, and which could threaten the mass of troops.”[19] Signallers maintained constant communication. The march usually proceeded up Pancake Lane, later known as Progressive Avenue,[20] and returned down the River Road. Marching bands and various ditties maintained morale and the marching rhythm. Sore, blistered feet were the usual complaint afterwards, but on at least two occasions tragedy occurred. During a severe electrical storm, lightning struck the coffee tent on the Heights. One man was killed, two were blinded, and forty-eight injured, many having been burned when their straw “cow’s breakfast” hats burst into flames.[21] On another occasion when a summer storm became violent, nine soldiers were killed when lightning struck a willow tree, under which they had sought refuge.[22]

The supreme route march was the Great Trek of 1915 from Camp Niagara to the Exhibition Grounds in Toronto. On October 25 the first battalion left for Toronto, and for each of the next eleven days another battalion broke camp. Every night on the Commons before their departure the battalion would have a huge gala bonfire, around which they marched “shouting and singing and having an hilarious time.”[23] One Scottish battalion, perhaps “excited by the pipes” (this was officially a dry camp), burned down the judges’ stand on the racecourse.[24] The eighty-seven mile trek was conducted at a relatively leisurely pace; six days of marching on dirt roads with a rifle and a sixty- to seventy-pound backpack. The worst part was the dust. “You couldn’t tell your own pal’s face because of the sweat and the dust caked on his face.”[25] Some were fortunate to finally have a bath on the fifth day in large vats of the St. Lawrence Starch Company in Port Credit.[26] Another special treat was at Fruitland, where all the men were presented with slices of pie served by “lovely girls.”[27] Within a few weeks of reaching Toronto they were on their way to Europe.

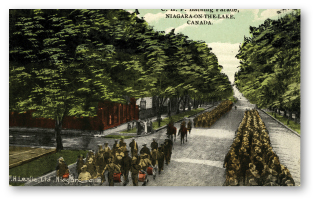

CEF Bathing Parade Niagara-on-the-Lake Canada, postcard, circa 1916. Heading for the icy-cold waters of Lake Ontario.

Courtesy of the author.

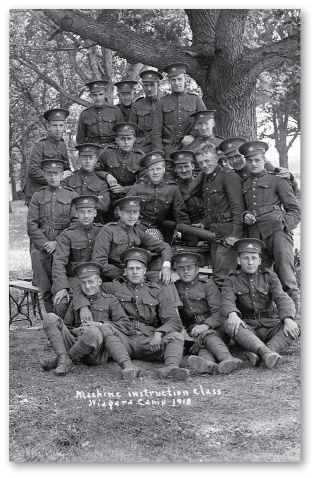

Machine Gun Instruction Class Niagara Camp 1918, photo postcard, 1918. This photograph was taken at the edge of Paradise Grove. Note the puttees on the trainees’ legs.

Courtesy of the author.

The cavalry brigades were encamped between the Fort George ruins and Paradise Grove. They followed a similar routine, although much of their time was spent with the horses: grooming, drills, and so forth (see chapter 15). As one cavalry officer recalled, the general order of responsibility was always “Guns first, horses second, men last!”[28]

Many other units also trained at Camp Niagara, including artillery batteries, machine gun batteries, armoured car and motorcycle detachments, field engineers, and various detachments of the Canadian Permanent Army Service Corps. University students were trained through the recently formed Canadian Officers Training Corps. Although most of the men were encamped on the Fort George Commons, hundreds of infantry tents were also pitched on the Mississauga or “Lake” Commons, formerly the Niagara Golf Course. At the far end of the latter was a small firing range.

There were always several brass bands training in camp, as well as buglers and trumpeters. In addition to accompanying the battalions in various endeavours they would occasionally engage in competitions and tattoos, to which the townspeople were invited.

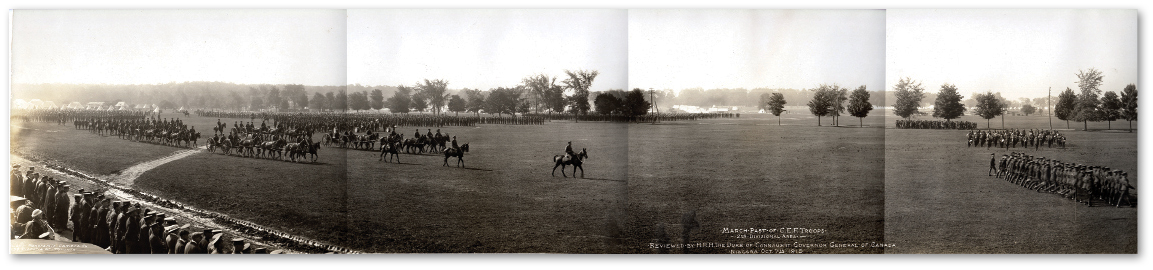

Panoramic View of a March Past on the Commons, photo, 1915. This march past of CEF troops, 2nd Divisional Area, was reviewed by HRH Duke of Connaught on October 7, 1915, just prior to the start of the Great Trek.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #972.741.2.

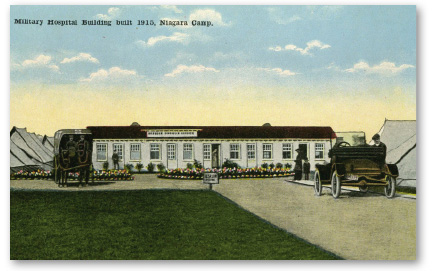

Military Hospital Building Built 1915, Niagara Camp, postcard, 1915. This hospital complex was built inside the remaining earthworks of Fort George. The horse-drawn ambulance on the left is marked with the Red Cross.

Courtesy of the author.

The health of the recruits was of prime importance. The soldiers’ feet were a special concern, and regular “foot parades” were conducted by the medical staff. Another monthly medical ritual was known colloquially as the “short arm inspection” in which the men were lined up and checked for any signs of venereal disease.[29] (A graphic film on the dangers of venereal disease was also shown to the men.) The men’s lines were inspected every day, and any concerns were reported to the camp commandant. Rules for camp cleanliness were strictly adhered to. The town’s water supply was the source of the camp’s drinking and washing water. This was tested several times a day in a laboratory unit in the old Navy Hall building that was also the site of a six-chair clinic operated by the Dental Corps. Mass inoculations and vaccinations were also conducted periodically in this historic building. The camp’s stationary hospital consisted of rows of tents for the patients within the bastions of the ruins of Fort George. The operating tent was replaced in 1915 by a more permanent operating room officially opened by Lady Borden, wife of the prime minister. At the far end of the enclosure were the tents of the Army Medical Corps. At the end of the season any remaining in-patients were transported by a special Red Cross hospital train to Toronto.[30]

Although the men were kept busy with their training, recreational activities were also promoted to discourage “idle” activities. Besides swimming, there were pick-up games and more structured inter-battalion competitions in lacrosse, baseball, football, and track and field. Battalion canteens were a popular refuge for refreshments and camaraderie. Thanks to Sam Hughes, Camp Niagara was declared “dry.” This may explain why the graduates were noted to be the thirstiest beer drinkers of all the overseas battalions once they reached Europe.

All trainees were encouraged to send letters or postcards to their families and friends back home. This was the golden age for postcards, and, as any card collector will attest, many have survived from the Great War. They were readily affordable for both officers and the ranks. For two cents postage a soldier could send a postcard with a message showing various activities or buildings at Camp Niagara, or he could send more expensive photo cards of his battalion or even of himself standing in front of his tent. The postal station in camp used the cancellation “Field Post Office Niagara Camp Ont” plus date.

Camp Niagara 1918, photo by A. Hardwick, 1918. On the right is the administrative building and in the centre is the camp’s field post office marked with a two-colour flag in front.

Courtesy of Peter Moogk.

Field post office cancellation, Niagara Camp, postcard. This is the most common stamp cancellation used in Camp Niagara’s busy post office.

Courtesy of Peter Moogk.

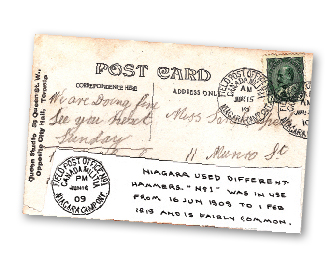

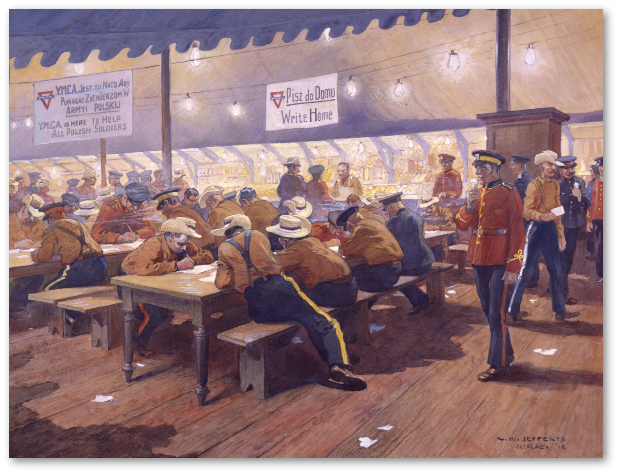

The YMCA operated large tents on both Commons. There souvenirs, various amusements, sports, games, reading room, and even movies were available.[31] Volunteers in the tents encouraged and even assisted the soldiers in writing their letters and postcards home. Sing-songs and concerts were occasionally offered.[32] The popular entertainment group The Dumbells performed at Camp Niagara.

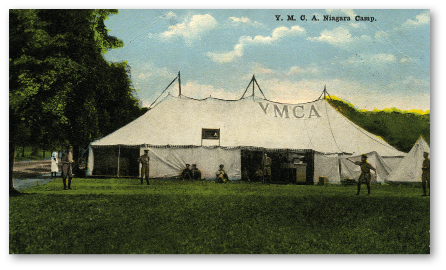

The St. Andrew’s Brotherhood of the Anglican Church just outside the camp provided similar services and was known for serving especially good food.[33]

There were many other diversions outside the camp, including a vaudeville theatre and a movie hall, built on Queen Street by a Mrs. Norris.[34] There were several shooting galleries and “refreshment stands” in town. Many shops popped up along Picton Street selling souvenirs to the soldiers and their families who arrived by steamship to visit the camp on Sundays. In the warmer summer months concerts and dances were offered in Simcoe Park.

As with any military encampment there were the usual camp-followers: the sutlers, the boot-leggers, the card sharps, and “the ladies.” Harry James recalled as a boy being told that a long wagon-caravan of “Gypsies” rumbling by along Queenston Street in St. Catharines towards Niagara was on its way to Camp Niagara.[35]

The training of overseas battalions and other groups continued at Camp Niagara for five years. It was not until 1917, however, that a standardized fourteen-week training course was introduced. (During the winter the training continued at the Exhibition Grounds in Toronto.) At times there were as many as eighteen thousand personnel in camp either in various stages of training or as support staff. For many, these weeks spent at Camp Niagara would be their last on Canadian soil.

YMCA, Niagara Camp, postcard, circa 1915. There were three large YMCA tents: one on the Mississauga Commons, another serving the Fort George encampment, and later a third tent for the Polish trainees.

Courtesy of the author.

St. Andrew’s Brotherhood, photo postcard, circa 1915. Just at the edge of camp the Brotherhood of the Anglican Church served especially good food.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

The initial patriotic and optimistic enthusiasm of 1914 waned as the growing lists of casualties in Europe appeared in the daily newspapers and local families received word that loved ones were not coming home. Recruitment posters became more forceful, some even directed to young women to encourage their “best boy” to enlist. Because so many men were in training or overseas, women were assuming much more responsibility. Although they continued their important roles as nursing sisters and ambulance drivers both at home and abroad, they were now working at occupations once restricted to men in the munitions factories and at clerical jobs in banks and insurance offices. Locally more women were working the farms, canning factories, and operating the canteens.

With the grim reality of horrific battles still raging in Europe and the prospect of voluntary enlistments dropping off, the Canadian government introduced conscription under the Military Service Act of 1917. Although divisive for the country, it did continue the stream of recruits to Camp Niagara.

What a relief when the Armistice was finally signed on November 11, 1918, ending the most destructive global war ever — the war to end all wars. However, the overwhelming joy was somewhat tempered by the Spanish Influenza, which was spreading around the world. Camp Niagara would not be spared, although the overseas battalions still in training were not as severely afflicted as the Polish army in training five hundred yards away.

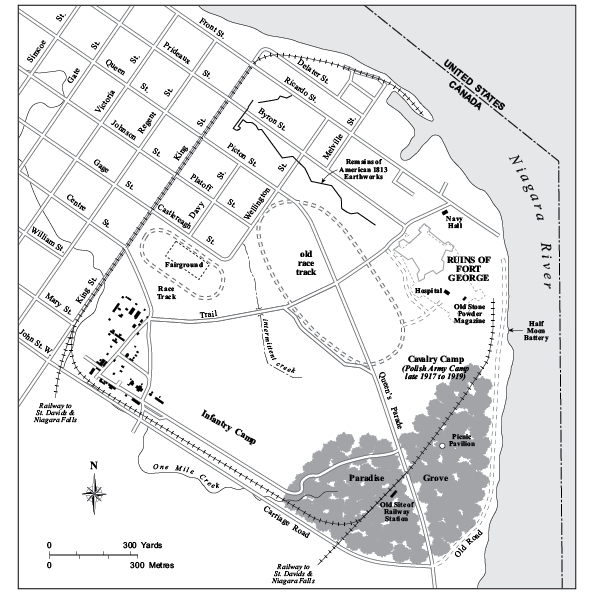

Fort George Military Reserve/Commons 1917. In 1917 Camp Niagara was probably near its peak capacity. In the fall of 1917 the cavalry camp was moved towards the western end of the camp and the new year-round Polish army camp was established.

During the Great War’s years, over a hundred thousand young men spent several weeks on the grassy plains of the Commons. Each one of them had hopes and fears, dreams and demons, friends and loved ones. For many these would all be snuffed out within months. Others would endure years of physical disabling pain and/or mental anguish. Some would faithfully attend cold rainy Remembrance Day ceremonies with aging comrades for the next eighty years as their numbers relentlessly dwindled away.

The preservation of the Commons is a testament to their sacrifice.

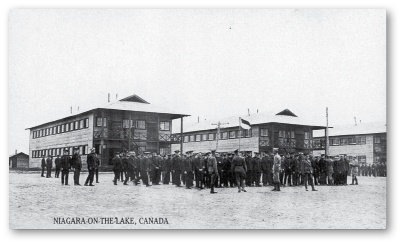

Polish army camp, photo postcard, 1918. Four barracks were quickly erected in the fall of 1917 on the former cavalry campsite between the ruins of Fort George and Paradise Grove.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

The Polish Army

The training of the Polish army at Camp Niagara is surely unique in the annals of Canadian military history. The story is even more remarkable because it has inspired an annual commemorative pilgrimage to Niagara-on-the-Lake ever since.

For over 125 years the homeland of Poland had been partitioned by Austria, Germany, and Russia. The military and social upheavals created by the Great War encouraged ex-patriot Poles to form a Polish military force to fight alongside the western allies in France with the ultimate goal of repatriating their country. By 1917 thousands of young Americans of Polish descent had volunteered, but with the United States still at peace with Germany, Congress refused to allow their training on American soil. While touring the United States, renowned Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski persuaded President Woodrow Wilson to support a scheme whereby Polish Americans would be trained by Canadian officers in Canadian camps, all paid for by the French government.

Bayonet Practice Niagara Camp, artist C.W. Jefferys, sketch, ink on paper, 1919. Jefferys was commissioned by the federal government to paint various scenes of life in the Polish army camp both in summer and winter.

Beaverbrook Collection of War Art © Canadian War Museum, 1 9710261-0213.

In early 1917 the first of 295 young Polish American “probationers” began intensive training as officers in the School of Infantry at Camp Borden, north of Toronto.[36] In June the president of France officially authorized the formation within the French army of an autonomous Polish army. Early in the morning of September 28, the Canadian staff and new Polish officers arrived at Camp Niagara to establish their campsite on the eastern half of the Commons. Shortly thereafter, over three thousand raw recruits arrived by train from Buffalo. As this was to be the first winter Camp Niagara, the recruits began construction on four tarpaper-covered barracks situated between the ruins of Fort George and Paradise Grove. Deep trenches for water and sewage lines below the frost line had to be dug quickly as well. Completion of the barracks by early December only provided accommodation for 1,200 men. With an unusually early and severe winter, some two thousand men had to be billeted throughout the town, all provided free by the citizens of the town: at the town hall, the bath house, unoccupied hotels, empty stores, canning factory, the Sherlock house and garage, and several buildings down by the waterfront.[37] The band was lodged on the main floor of the Masonic Hall. Many officers enjoyed the comforts of the Plumb House on King Street[38] and the old Western Home.[39] The actual headquarters was in the American (later King George III) Hotel on Delater Street. Visiting family members usually stayed at Doyle’s Hotel on Picton Street, which was owned by a Polish family.

Polish Soldiers Crossing the Commons, artist C.W. Jefferys, sketch drawing, carbon pencil on paper, 1918.

Beaverbrook Collection of War Art © Canadian War Museum 19710261-0241.

Over the next eighteen months a constant turnover of volunteer recruits arrived and left by train throughout the day and night. At any one time there were approximately four thousand eager recruits in camp undergoing a month of rigorous basic training. Instructions were given in British and French drill, and in English or Polish languages by acting Polish officers and NCOs under the supervision of Canadian officers. No musketry training or rifle drill was given. Two brass and one bugle band were trained in camp. The volunteer recruits were paid the princely sum of five cents per day; acting officers received $1.12 per day. In addition, each man was entitled to a premium of $150 per year.[40] Initially the recruits were outfitted with surplus discontinued nineteenth-century Canadian militia uniforms. Instead of the drab khaki uniforms of the regular expeditionary overseas forces still training at Camp Niagara, Polish recruits marched in the more colourful scarlets, dark blues, and rifle greens of the old militia.[41] Eventually they were outfitted with the “horizon blue” uniforms of the French army, and so became known as the “Blue Army.”[42]

After their month of training, the recruits decamped by train back to Buffalo for eventual embarkation to Europe via New York or Halifax. Even after the Americans declared war on Germany, Congress refused to allow the training of a foreign army on American soil. Nevertheless, for a short time overflow recruits were allowed to camp at a “Depot” at Fort Niagara. Another depot at St. Johns, Quebec, now Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, also accepted an overflow of recruits for a short period of time.[43]

Soldiers of the Polish Army in the YMCA Tent at the Camp Niagara, Niagara-on-the-Lake, artist C.W. Jefferys, gouache, watercolour, graphite pencil on board, 1918. Note that the Polish trainees are wearing old Canada militia uniforms and the signs are in both Polish and English.

Beaverbrook Collection of War Art © Canadian War Museum 19710261-0207.

Polish Soldiers Bathing at Niagara, artist C.W.Jefferys, watercolour on paper, 1918. As with all the other trainees at Camp Niagara, the Polish volunteers took part in their own bathing parades. Note on the right is Fort Mississauga and Fort Niagara beyond, across the river. Guards served as lifeguards and kept away the curious.

© Canadian War Museum, 20070151-001.

In the spring, the camp returned under canvas. The following winter most of the recruits had to be billeted once again, but on this occasion, there was a nominal fee.

The supervising Canadian officers, including the medical staff, were headed by Camp Commandant Lieutenant Colonel Arthur D’Orr LePan, who at age thirty-two already had a distinguished career, both in the military and education. Many of the officers had served overseas in the Boer War or the Great War. One officer of note, Captain Alexander G. Smith, a Native of the Six Nations Reserve, had served with distinction in France and been awarded the Military Cross.[44]

The Polish camp on the Commons was officially named Tadeusz Kosciuszko Camp after the American Revolutionary War hero Kosciuszko who fought bravely with George Washington — a strange irony as the camp was only a stone’s throw from the site of Loyalist John Butler’s Rangers’ Barracks. Poland’s national emblem, the white eagle, watched over the campsite. On a summer’s evening haunting and melancholic Polish folk music could often be heard drifting across the Commons. During their hard-earned rest periods, the recruits, wearing the czapka, the traditional square-topped headdress of the Polish military, were often seen “dancing the mazur [sic] and the polka on the green.”[45]

Although the local citizenry were initially concerned when these young “aliens”[46] first arrived, these dedicated young men, so passionate about their homeland, soon were accepted with open arms. It was not unusual for crowds of townspeople to turn out for their emotional departures; many homes were opened for billets; new books on Polish history and culture appeared in the library. And there was other support for the men. The Canadian YMCA furnished a large tent on the Commons as well as a recreation hall and reading room in town. Facilities included halls for three “movie picture machines,” a branch post office, and bank. Assistance was freely offered to the recruits to write letters home and even write wills. Recreation halls were converted into chapels on Sundays. Arrangements were made for sports and entertainment. Profits from the canteen were donated to the soldiers.[47] The American Red Cross sisters travelled regularly to Niagara with their motor ambulances to distribute “comfort kits” to each of the men.[48] They also established a “service station” for relatives visiting the camp.

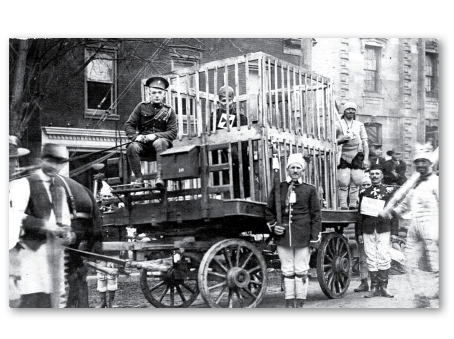

Armistice parade, photo, 1918. The Polish volunteers organized a huge special parade on Armistice Day (somewhat prematurely). A “Kaiser” in a large cage was paraded across the Commons and through town.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

The soldiers responded in kind. One event long-remembered by the locals was a special parade on Armistice Day.[49] The recruits and their Canadian officers mounted a huge parade, including ordnance, bands, flags, banners, and a float with the “Kaiser” in a cage which marched from Camp Kosciuszko, across the Commons, through town, and out to Fort Mississauga. Some of the recruits enjoyed carving ice sculptures in Simcoe Park and down by the waterfront, much to the delight of local children.[50] The supervising Canadian officers and the locals all agreed that the Polish recruits were “the best behaved soldiers who served [at Niagara] at any time.”[51] On one occasion Father Rydlewski, who had left a large comfortable church in Pittsburgh to serve as chaplain to the recruits, appeared at a meeting of town council. After receiving a warm commendation for his men’s exemplary behaviour he explained, “But I’m afraid gentlemen, they wouldn’t have been so good if they could have got the viskey.”[52] A few of the boys did apparently succumb to another vice: an upstairs apartment on Queen Street was staffed by “ladies from Buffalo.”[53]

In recognition of the historic significance of the training of the Polish army on Canadian soil, several distinguished personages visited Camp Kosciuoszko. These included HRH Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught,[54] the Duke of Devonshire, the then-Governor General of Canada, and Polish Prince Poniowtoski.[55] But the most revered visitor was Paderewski himself who had worked so hard to establish a Polish army in exile. He was honored with a march past on the Commons. He later became prime minister of the newly independent Republic of Poland.

During the eighteen months of its existence 22,395 men were trained on the Commons for the Polish army, with 20,720 actually sent to France. Less than 1 percent were enlistments from Canada, the balance coming from the United States.[56] These statistics, however, belie an underlying tragedy that struck the young “rugged strong” Polish soldiers.[57] In early September 1918 the first cases of Spanish Flu in Canada appeared among recently arrived recruits from the United States. Part of a worldwide pandemic of viral influenza originating from the American Midwest, the virus spread quickly through young soldiers in over-crowded barracks all over North America and then the rest of the world. The deadliest disease in human history, it was eventually responsible for more deaths than the Great War.[58] At the Polish camp on the Commons the medical personnel were soon overwhelmed with hundreds of cases resulting in twenty-four deaths during the initial wave that lasted six weeks. A second outbreak in 1919 was mercifully not quite as severe. Interestingly, it was several weeks after the Polish outbreak before the first case of influenza presented among the Canadian soldiers encamped near Butler’s Barracks at the far end of the Commons. Of the forty-three deaths at Camp Kosciuoszko, at least twenty-five (including a Canadian officer in the Polish camp) were directly attributed to the Spanish Flu.[59] Many of the stricken Poles were buried in the parish cemetery of St. Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski, photo, 1918. In July 1918 the world-renowned pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941) was honoured with a march past on the Commons. He would later become prime minister of the free Republic of Poland.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #97911.2

In recognition of the sacrifices of these young men for their beloved homeland and for the support given by the citizens of Niagara, members of the Polish community in North America make an annual pilgrimage to St. Vincent de Paul cemetery on “Polish Sunday,” usually the second Sunday in June. A special service is held in the “Polish Enclosure,” which is the location of the burials of twenty-five young men and one of their chaplains, Father Jan Jozef Dekowski, who asked to be buried here. This hallowed place has been designated as sovereign Polish soil. In September 1969, Karol Cardinal Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II, visited the site.[60]

Volunteers from the Red Cross, photo, 1918. Many local women, some of whom were former nurses, volunteered to work with the Red Cross during the influenza outbreak at the Polish army camp. They encamped on the Commons near the Polish barracks.

Courtesy of Pat Simon.

Sovereign Poland in Niagara-on-the-Lake, photo, 2011. This hallowed piece of land in St. Vincent de Paul cemetery was given to the Government of Poland by the Government of Canada to commemorate the Polish trainees who died at Camp Niagara and in recognition of the Polish people as valued allies.

Courtesy of the author.

One of the last surviving veterans of the Blue Army recalled:

… in Canada, it was just like having good parents, you know. The Canadian people were wonderful and they are wonderful now. The Canadians welcomed us like brothers.[61]

There was one local citizen who became especially connected with the Polish army camp. Elizabeth (Lizzie) Masters Ascher (1869–1941) was born in Niagara[62] and became a journalist, writing articles for newspapers in St. Catharines, Buffalo, and Toronto. During the Great War she became particularly interested in the Polish army camp, and during the Spanish Flu epidemic she fearlessly cared for stricken young recruits. Even after the last volunteer had left Camp Kosciuszko she tirelessly spearheaded local relief efforts to collect clothing, medical supplies, and money for villages in newly independent Poland.[63] She even tended the graves of the fallen. For her dedication she was awarded Poland’s highest civilian honour, the Order of Polonia Restituta. As part of the annual Polish Sunday commemorations a wreath is placed on her gravesite in St. Mark’s Cemetery.

Lt. Col. A.D. LePan Commandant and Staff Polish Army Camp. Photo by Ficar, January 15, 1919. The Polish army camp at Niagara was demobilized in early 1919. By this time most of the Polish trainees were fighting in Europe against Russian Bolsheviks for the independence of their homeland.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, # 991.737.