Chapter 16

Global War Again, 1939–1945

In the late summer of 1939, with summer militia camp just completed and the threat of war in Europe imminent, B Company of the Royal Canadian Regiment was ordered to remain in Camp Niagara. Within days, its commander, Colonel Willis Moogk, received orders to erect nine miles of barbed wire fencing on the Commons for an internment camp to house enemy aliens gathered up by the RCMP. After five frantic and strenuous days the job was completed and celebrated with a huge bonfire on the Commons. When Moogk called his superiors the next morning to announce completion of the job, there was a long pause followed by “Haven’t you heard? It’s all been changed!”[1]

Needless to say the locals would not have been pleased with the presence of a POW camp and the constant prospect of desperate escapees within town limits.[2]

Instead, Camp Niagara once again became the military training ground for tens of thousands of Canadian men and women. Most small communities in Ontario experienced a great exodus of their young people to the war effort overseas or to urban factories; however, Niagara-on-the-Lake became the temporary home to thousands of anxious soldiers about to leave for Europe, many of whom would never return home. For the sleepy little town of Niagara just emerging from the Great Depression, Camp Niagara provided once again a tremendous stimulant to the town’s economy and psyche.

In many respects the Camp Niagara experience in the 1940s was similar to that of the Great War. However, with increased mechanization and more sophisticated weaponry, training became more specialized. Cavalry and horse-drawn wagons, although still present early on, were soon gone — the stables were converted into garages and workshops.

But this time, in addition to its traditional role as a training facility, Camp Niagara was to be the home base for regiments guarding the Niagara Peninsula’s “Vulnerable Points.” Throughout the Second World War there was genuine concern by the Canadian military that enemy terrorists would attempt to sabotage the major hydroelectric plants at Queenston and Niagara Falls or the international bridges, or that they would try to disrupt the flow of military supplies through the Welland Canal. Moreover, guard duty was required along the border to capture and intern “enemy nationals” attempting to escape into the United States prior to its entry into the war in late 1941. Many regiments stationed at Camp Niagara spent a third of their time training at Niagara and two thirds rotating through “Guard Posts” at sites such as Queenston Heights, Niagara Falls, Chippawa, and Allanburg.

Military Reserve, 1941. With the exception of the restored Fort George and Navy Hall sites, Camp Niagara occupied the entire Military Reserve. As it was now a year-round camp, and many new permanent buildings were erected, including the avenue of H-huts between Paradise Grove and Fort George and the new hospital on the western edge of the Paradise Grove. Provost Road was eventually extended to meet King Street at the end of Mary Street.

Another innovation for Camp Niagara during the Second World War was the “electrification” of the camp. Candlelight was replaced by electric wiring and lamps in the officers’ tents, messes, canteens, and quartermasters’ stores.[3] With the canvas tents so inflammable there was always the risk of fire as the insulation on the wiring would wear off due to constant chaffing from the shifting tents. Fire alarms were frequent. With the cold fall weather of 1939 setting in, the ever-resourceful troops took advantage of the recently installed hydro lines by hooking up electric heaters, electric razors, and electric toasters to the outdoor wires, which overloaded the transformers. It wasn’t long before the order came down from brigade headquarters that “All ranks are warned that, on no account will they interfere with electric wiring or appliances, either inside or outside of buildings in camps or barracks,”[4] and so it was back to basics. The use of candlelight and tobacco smoking under canvas would continue to be very risky practices.

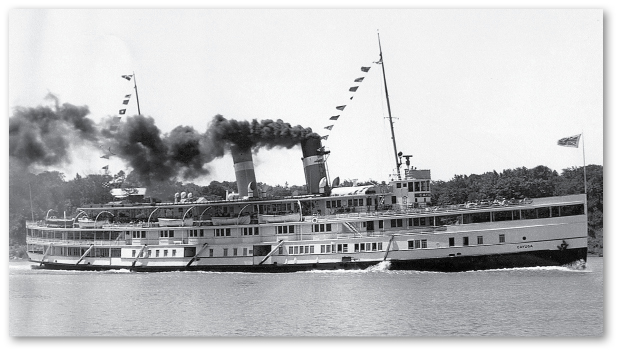

The SS Cayuga, photo, circa 1939. During the Second World War, the SS Cayuga was the only trans-lake passenger boat still in operation. Thousands of soldiers and their visiting friends and family came to Camp Niagara aboard “the graceful lady.”

Courtesy Pat Simon and Joe Solomon.

As with the previous war, most of the soldiers arrived at Camp Niagara by steam railway or passenger boat. Only a few were brought in by bus or truck convoy due to the severe limitations on gasoline during the war years. The only railway into town was still the Michigan Central owned by New York Central, which cut across the township along Concession 1, now called Railroad Street (see chapter 18). With connections at St. Davids and Niagara Falls, soldiers could be brought in from all over southern Ontario.

The only passenger boat still in operation during the Second World War was the steamship Cayuga, which made the two-hour trip across Lake Ontario from Toronto several times a day. It could carry 2,500 passengers and ran eight months of the year (see chapter 18).

Once the soldiers had disembarked from their train or boat they would fall into formation and march to the campsite, led by their regimental band or, in the case of the Scottish regiments, their pipers, thus proudly announcing their arrival to their brothers in arms and welcoming townspeople.

There were some motorized vehicles in camp. The Royal Canadian Army Service Corps erected a fifteen-car garage and a gasoline filling station along John Street East. The Camp’s fire truck had its own station. Jeeps and buses were used sparingly, the latter to transport troops up to the vulnerable points, although the men would frequently march to these sites. In July 1940, twenty-one new trucks arrived from the Windsor truck factory, and these were used primarily by military truck trainees.[5] Bren Gun universal carriers and even a Sherman tank arrived later in the war and were kept at the rifle range on the lakeshore properties.

As with previous generations of soldiers, the enlisted men were housed in canvas bell tents. For this camp the men usually slept six to a tent, feet towards the central pole on straw paliasses laid on floorboards. NCOs slept two to a tent while the regimental sergeant major and the officers had a tent to themselves. Some officers even had some camp furniture under canvas. The summer militia trainees continued to sleep under canvas throughout the war years. As the war effort dragged on and Camp Niagara became a year-round destination for the overseas battalions in training, more substantial buildings were erected. Eventually, ten large H-hut barracks along with outbuildings were erected on the Commons northeast of Queen’s Parade, just north of Paradise Grove. A drill hall with a small indoor firing range was built on the opposite side of Queen’s Parade. A new military hospital was built on the edge of Paradise Grove. However, many of the century-old buildings of Butler’s Barracks were also used: the officers’ mess and quarters became the administration building. The nearby barrack officer’s quarters became the Nursing Sisters’ quarters. The two-storey barracks, gun shed, and commissariat stores were used for storage. The compound consisting of the old Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters and barrack master’s quarters continued to be the headquarters. The previously abandoned flower gardens were rejuvenated, trees were planted along the parade roads, and even ornamental shrubs were added to help beautify some of the buildings’ entrances.[6]

The Canadian Women Army Corps (CWAC) stationed at Camp Niagara was housed off-site in a large clapboard house on Regent Street, now the Morgan Funeral Home. A large coach house at the rear, a smaller residence on William Street, and the large house at the corner of King and Mary (now known as Brockamour) provided extra accommodation. The sleeping arrangements consisted of bunk beds with two or more women sharing a room; kitchen facilities were available for snacks.[7] Many of the CWACS (affectionately known as the Quacks) performed secretarial and stenographic duties in various camp offices; they were also assigned to operate the camp switchboard 24/7. Delivering the official mail around the camp was another responsibility.

Some women were trained in various trades with the Ordnance Corps, including motor mechanics and welding and would be paid accordingly. Although the CWACs had received basic training before being assigned to Camp Niagara, on occasion they were expected to take part in route marches and parades. Marching with the men could prove very frustrating: generally the stride of the women was significantly shorter than their male counterparts; hence, they were often out of step.[8]

The CWACs’ barracks were strictly off limits to the men. A man courting a CWAC would have to present himself at the front desk, whereupon his date would be summoned. With so many men in camp, the women could be very choosy. Although the more highly paid officers were considered prime candidates, it was forbidden for officers to date “other ranks” … but then rules were bound to be broken, especially with affairs of the heart!

Married officers’ wives and children were housed in private homes in town.[9]

Winter Quarters, Niagara Camp, souvenir card, circa 1942. To accommodate the trainees through the winter months, ten large H-hut buildings were quickly erected. This photo is taken from near the river bank looking westward towards Paradise Grove.

Courtesy of the author.

Once the newly arrived active servicemen were unpacked and received orientation, training at Camp Niagara commenced with basic section drill, squad drill, platoon drill, rifle, machine gun, and hand grenades training. On the 30th of each month a new detail was added.[10] Some of the training was carried out at the rifle range on Lakeshore Road. As with previous generations of trainees these daily parade marches out to the Lakeshore Road properties were led by rousing regimental bands, much to the excitement of the locals, especially the youngsters who were often seen excitedly beating their homemade toy drums by the roadside.[11] If they were lucky the trainees would get back to camp in time for dinner in the mess hall. Newly acquired skills in defensive manoeuvres and tactics were put to the test in mock battles conducted on the vacant land to the west of the rifle range. (This land has remained contaminated and posted “off limits” for over half a century for fear of unexploded ammunition from the Camp Niagara years. Now transferred from the Department of National Defence to Parks Canada, the future of these lands is uncertain.)

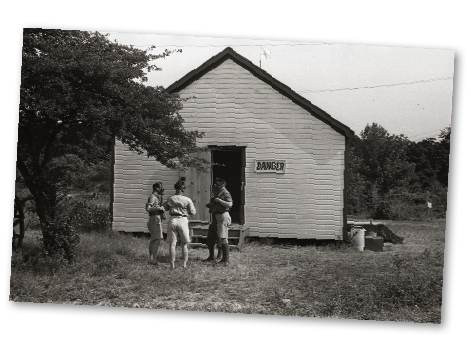

All units had to report to the dreaded “Gas Hut.” This actually consisted of three buildings: a gas chamber and two gas stores and/or quarters, all of which was surrounded with barbed wire, in Paradise Grove at the south end of the camp. Here recruits were taught to don protective clothing and respirators in a fog of gas, but as part of the training they would also be submitted to the horrors of an unprotected gassing so that they would know what to expect. It was suspected, however, that the authorities were experimenting with various new gasses and antidotes that were tried on the men.[12]

One of the many strengthening and conditioning exercises the men were subjected to at camp was the occasional twelve kilometre parade march up to Queenston Heights and then back, sometimes in full battle dress.

Gas huts, photo, 1939. The dreaded gas huts were three small buildings situated in an area surrounded by barbed wire, deep in Paradise Grove.

Courtesy St. Catharines Museum, The St. Catharines Standard Collection, S1939.44.10.1.

Taking a break, circa 1942. Men taking a break during intensive training exercises on the Commons. The drill hall can be seen in the background.

Courtesy Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2011.020.001E.

Although the militia would continue to attend the summer camps “the mood was more serious and the training more focused and intense.”[13] In fact, during the Second World War the militia often formed a 2nd battalion of a regiment, many of whom would eventually be transferred to full active service in the regiment’s 1st Battalion.

As previously mentioned, two-thirds of the regiment’s time at Camp Niagara was spent rotating through the vulnerable points where they were billeted. Generally the men found the shifts in the guard huts very boring and lonely. They much preferred the intense training and camaraderie at the camp. As the war dragged on and the training of the active regiments accelerated, their guard duties were taken up by the Veteran Guards of Canada, considered too old for battlefront duty. Perhaps out of boredom, some of these “old guards” became heavy drinkers, which alarmed the townsfolk.[14]

A successful military encampment depends on three key components: discipline, dependable communications, and the good health and well-being of the soldiers. The Canadian army adopted the strict traditional no-nonsense top-down chain of command so characteristic of the British Army. The esprit de corps of a regiment required all components to act quickly and appropriately in concert with one another, regardless of adversity. Unity of appearance and the soldiers’ standard of dress (for example, the “spit and polish” tradition that all boots, buttons, and badges be kept highly polished) all contributed to a soldier’s personal pride in one’s regiment. Soldiers, identified by special armbands, were also assigned on a rotation basis to serve as camp and regimental military police (provosts).[15] There was also tight perimeter security to attempt to prevent unauthorized persons from entering or leaving the camp. Although there was no actual barrier fence, the few roads into camp were controlled by guards manning special gates. It was always tempting for locals to take shortcuts across the camp.

When a new regiment arrived, one of the very first duties was for the regimental signallers to establish and operate their own field switchboard for communications with all units within the regiment, but also with the main central camp switchboard and with the vulnerable points installations throughout the Niagara Peninsula. From the 6:00 a.m. wake-up call of reveille to the lights out reminder at night, the regimental buglers continued to play an important role in the daily routine of the soldiers.[16] Buglers called the men to meals, marches, and even announced the arrival of the mail. Lyrics were often matched to the distinctive calls that became such a part of their everyday existence: one ditty for the mail call ran, “a letter for me, a letter for you, a letter from Lousy Lizzie.” The Scottish regiments had their pipes and drums to play their distinctive calls.[17] Traditional “dinner sets” were also played in the officers’ mess. Depending on the wind direction, the frequent bugle and pipe calls could be heard throughout much of the town. In fact, citizens of Youngstown, New York, across the river, bemoaned the loud early-morning skirling bagpipe calls emanating from Camp Niagara.[18] Of course similar wake-up calls would also be heard coming from the American training camp at Fort Niagara after 1941.

Song at Twilight, Niagara, souvenir card, circa 1940. The Scottish regiments always had their pipers who could be heard throughout town and across the river.

Courtesy of the author.

The health of the men and women was of prime concern. The regimental medical officer was responsible for the welfare of his servicemen, and any concerns were to be reported to the camp’s commanding officer, stat. Vaccinations and inoculations were kept up to date. All men’s hair was to be kept short. In good weather barbers would be seen cutting hair outside under a shady tree. An enterprising barber could perform seventy haircuts per day.[19] The new arrivals were subjected to lectures and graphic movies on the spectre of venereal diseases.

Understandably, special attention was paid to the men’s feet, with special instructions issued that feet were to be bathed daily and clean socks worn. Daily showers were supplemented with the mandatory use of footbaths containing antiseptics, which were changed daily. However, many soldiers complained that such communal immersions only increased the risk of athletes’ foot.[20] Special care was also given to the proper fitting of soldiers’ boots.

Camp Life, “NEXT,” photo postcard, circa 1915. Throughout its ninety-five-year history, outdoor haircuts were a tradition at Camp Niagara. In this scene the impromptu barbershop has been set up on the edge of Paradise Grove. Here the men appear to be in civvies and the barber and two of the customers are wearing the straw “cow’s breakfast” hats.

Courtesy of the author.

A new hospital building (the eighth hospital to be built on the Commons) was erected on the edge of Paradise Grove, and included a thirty-six-bed open ward and a twenty-eight-bed isolation ward for those with communicable diseases. Even a fully equipped operating room was available. Regimental physicians and Nursing Sisters of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps staffed the hospital. The Sisters’ residence near the administrative headquarters was strictly out of bounds to all others.[21]

The Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps with the Ambulance Corps and Casualty Clearing Stations also trained at Camp Niagara. Unlike the horse-drawn ambulance wagons of the Great War, ambulances now were usually jeeps or small trucks often identified by a large red cross. Mock battles offered a great opportunity for field ambulance trainees to practise their newly acquired skills on mock or “notional” injuries. The commonest real wounds were embedded thorns acquired from the many native French hawthorn trees on the various camp sites.

Feeling ill, one would have the option to go on “sick parade.” After waiting for breakfast to be finished, you would report to a superior that you were not feeling well and then be escorted to the military hospital. Usually after a cursory exam by a camp doctor one would be instructed to go home and take an aspirin. Consequently, unless desperately ill, most trainees would simply avoid sick parade.[22] Moreover, too many days on sick parade would draw suspicions of malingering from one’s comrades.

The food at camp was generally wholesome and plentiful — all prepared on the premises. Soups and stews were popular fare in order to use up leftovers, even incorporating the skins of vegetables normally discarded.[23] Recycling was a necessity during the war years so even the cooking fats were either reused or sold for the manufacture of soaps and glycerine-based products including explosives. With all their rigorous activities, the campers would always have good appetites; the trainees could have as much food as they wanted as long as they ate everything they took. The method of cleansing their eating utensils also followed strict regulations. After scrapping off their mess tin plate and cutlery, the utensils were dipped into a bucket of hot soapy water, then a bucket of chlorine water solution followed by a third bucket of clean water and dried by simply waving them in the air as they walked back to their tent or barracks.[24] In the officers’ mess, the meal was served and entirely different protocol observed, befitting an “officer and a gentleman.”

Without indoor plumbing, outhouses were still much in use — the “honey pots” emptied daily by a contactor from town.

The mental health of the recruits was always a concern. For many, Camp Niagara was their first experience away from home and their loved ones. The ever-present spectre of impending warfare, the strict discipline, and the lack of privacy all weighed heavily on the minds of many. The YMCA set up a special area for the writing of letters and even supplied the stationery. The Salvation Army was always there for support. In an effort to meet the spiritual needs of the men and women, church parades were held with separate services for Protestants (St. Andrews, St. Mark’s and Grace United), Roman Catholics (St. Vincent), and Jewish personnel. After their respective services, the troops would reassemble at the old Fair Ground’s Race Track (now the site of the Veterans’ Carnochan sub-division) and march through downtown Niagara-on-the-Lake for a “march past” before dismissal. In the warmer weather, ecumenical Drumhead services were sometimes conducted by regimental padres on the Commons for soldiers and townspeople.

In camp, amateur theatricals and professional concerts[25] were staged and movies were shown weekly in the recreation centre. In 1941 the Brock Movie Theatre (now the Royal George ) opened, providing welcome entertainment for soldiers and locals alike. Many local organizations invited off-duty men and women to social activities in town including card games, dances, and theatrical productions; during the summer, strawberry socials, garden parties, and Friday and Saturday night dances in Simcoe Park welcomed the soldiers. The General Nelles branch of the local Legion opened its doors to the enlisted men as well. Starting in 1940, the Legion sponsored the Sunday Evening Song Service (SESS) in Simcoe Park during the warm summer months. Sacred and patriotic music with words projected onto a screen were performed by military bands or local musicians. These rousing sing-alongs, usually led by Archie and Charles Haines,[26] were enjoyed by all. At the season’s finale in September over two thousand people would be in attendance.[27] In the winter the locals and soldiers could skate to music on the ice rinks on the Commons or in Simcoe Park.

Many of the off-duty trainees would relieve some of their stress with a pint or two. The wet canteens and messes in camp had strictly controlled hours of operation. Some of the local hotels, restaurants, and beer parlours welcomed soldiers, but many were “Out of Bounds.”[28]

If a soldier were lucky enough to obtain a temporary pass out of camp, he could hitchhike in his uniform to St. Catharines, Niagara Falls, or even Buffalo for a few hours of shopping and recreation.

Sports also played an important role in relieving stress for the soldiers. League softball games with the other regiments, as well as civic teams, track and field events, hockey, soccer, boxing, and judo were all available.

Hockey players in camp for training, photo by Jack Williams, 1940. Toronto Maple Leaf hockey players including Red Horner, Syl Apps, Turk Broda, and Art Jackson get some rugby tips while in camp for military training.

Courtesy St. Catharines Museum, The St. Catharines Standard Collection, S1940. 30.4.3.

Occasionally there were visitor days. Friends and loved ones would usually arrive by the Cayuga and be met at the dock by taxis owned by Tom May and Steve Sherlock for transport to the camp.[29] Inspection of their living quarters and a tour of camp would be de rigeur; sometimes a demonstration practice, tattoo, or a march past would be performed for visitors and townspeople alike. Many souvenir shops in town catered to the servicemen and their families. The day would end with fond farewells. Some would never see their loved ones again, as many regiments were mobilized to Europe directly from Camp Niagara.

Another diversion for the servicemen was the War Savings Certificate campaign to help finance the war effort. In an effort to remind and encourage civilians to participate, the soldiers would march through the neighbouring cities of St. Catharines and Niagara Falls followed by a few army vehicles and an ambulance. Of course the officers and enlisted men would also be encouraged to buy the Victory Bonds, thus setting an example to the civilian population.[30]

Despite all these activities and support for the troops, tragedies still occurred. Kaye Toye, who has lived most of her life in the Dickson-Potter Cottage on John Street across from the Commons, recalls one peaceful summer afternoon suddenly being shattered by a single gunshot from the direction of the enlisted men’s tents. There was great commotion and she soon learned that a young soldier had taken his own life in his tent; his companions took many months to recover from the shock.[31]

Special guests, photo, 1940. The monotony of camp routine was sometimes relieved by visits of VIPs. In August 1940, Governor General the Earl of Athlone and his wife visited Camp Niagara. This photo was taken at the corner of King and Queen Streets looking across towards Simcoe Park. Note the railway tracks through the intersection.

Courtesy of the Judith Sayers Collection.

During the summer fruit season, with so many young people away for the war effort, the local farmers were always short of help. At 7:30 a.m. farmers’ truck would be waiting at the camp gates to whisk off-duty servicemen to the orchards for the day. The military pickers were well paid compared to army standards,[32] and they could eat as much fresh fruit as they wanted. Many of these same farms also hired young women, known as Farmerettes,[33] an added attraction for the young men to work the orchards. As the war dragged on the Veteran Guards were also called upon to help harvest the crop. Colonel Willis Moogk, perhaps in cahoots with his subordinates, reported another good use for Niagara’s fruit:

Military training is notoriously dry work, however, and liquor was becoming both scarce and expensive. Someone secured a local genius, who, with unwritten approval, set up a still in the camp. It yielded an alcoholic “screech” which [was] mixed with Niagara fruit juices to produce a very inexpensive and authoritative drink. Distribution to the various messes was arranged, and life was good once more — until some wretch tipped off the R.C.M.P. News of the departure of two of their operatives on the “Cayuga” somehow reached camp before the steamer cleared Toronto harbour. On their arrival nothing could be found but an alcoholic odour.[34]

With the much-anticipated announcement of VE Day on May 8 marking the end of hostilities in Europe, exuberant celebrations broke out spontaneously throughout much of the world — Camp Niagara and the town included. The CWAC on duty when the news arrived reminisced that “the colonel came tearing over and was phoning for the Provosts to go and board up downtown, the liquor store and all that.”[35] “There were men all over the [women’s] barracks.”[36] Two thousand citizens and soldiers attended a thanksgiving service in the park followed by a mile-long parade through town.

The 1,200-strong 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion returned to Canada after VE Day, and after a thirty-day leave of absence they reassembled at Camp Niagara in late July 1945 to prepare for duty in the Pacific. The men became very bored because “they had no weapons, no aircraft available for flying and no parachute equipment! They would roll call in bathing suits or whatever, then be dismissed for the day.”[37] For many of the men who had just returned from the horrors of European warfare, “the sunny and warm summer [of] ’45 made Niagara-on-the-Lake look like Paradise.”[38] With the announcement of VJ Day on August 9, similar celebrations erupted again in Niagara. Some of the soldiers headed to Buffalo and got themselves into trouble, and two sergeants were arrested by the Buffalo police. The commanding officer had to personally rescue them, thus defusing an international incident.[39] Eventually, the Parachute Battalion officially de-mobilized Camp Niagara.[40]

Generally, the men and women who trained at Camp Niagara and survived the war retained very fond memories of Niagara. Many often brought their families back to Niagara-on-the-Lake to look around town but especially to revisit the site of Camp Niagara — the Commons — and remember.