Chapter 17

The Final Years of Camp Niagara and the Military Reserve

With the Second World War finally over, the need for a year-round Camp Niagara with all its facilities quickly evaporated. The locals, at least for most of the year, could reclaim their Commons. Within two years of cessation of hostilities, the Department of National Defence (DND) hired contractors to demolish many of the camp’s buildings, including the historic former officers’ mess and quarters of Butler’s Barracks. Shocked by such wanton destruction of the town’s military heritage, the Niagara Town and Township Recreational Council purchased approximately fourteen acres of the Commons, which included the two historic buildings in the compound, and negotiated a lease for three other surviving historic buildings.[1] Meanwhile, the War Assets Board sold some of the buildings for removal offsite. Some were sold to veterans and converted into homes; one wing of an H-hut was moved to the corner of Simcoe and Gate Streets in town and renovated as the new Kirk Hall for St. Andrews Church. The camp’s gymnasium was moved to Davy Street for St. Vincent de Paul’s parish hall. Some buildings were moved to area farms to serve as barns or packing sheds. The large drill hall was dismantled and reassembled in Welland as the Welland Curling Club. Another dismantled H-hut was transported to Port Hope, Ontario, and used as an annex for the Dr. Powers’s School.[2]

For years, the raised grass-covered foundations of several of the early administrative buildings along John Street West served as silent reminders of the extensive collection of buildings of Camp Niagara and its predecessor, Butler’s Barracks. However, in the 1990s the foundations were leveled (to facilitate grass-cutting maintenance) with the promise from Parks Canada that the foundations would be outlined with flat stones — a commitment which so far has not been kept. The only temporary building on the Commons today, the small Company B barrack, was one of several constructed in the late 1950s or early ’60s. All the others were eventually moved off-site.

Trees planted at Camp Niagara during the Second World War still stand as living silent sentinels along the interior roads and walkways on which tens of thousands of Canadian soldiers have proudly marched. The old parade ground is now barely visible and the small oval running track nearby has disappeared. Meanwhile, Paradise Grove has gradually reclaimed the lands once occupied by the military hospital and the gas huts.

The present-day Genaire building just off King and Mary Street was originally a canning factory on lands purchased from the town. Established just after the war, Genaire continues to produce aeronautical equipment. A veterans’ housing site on the Commons, known as the Carnochan Subdivision or “The Project,” bounded by King, Nelles, Davy, and Castlereagh Streets, was designated for returning soldiers and their families (see chapter 22). An adjacent piece of the Commons was set aside in 1949 by the town as a sports park and eventually designated “Veterans Memorial Park.”[3] In 1965 the General Nelles branch of the Royal Canadian Legion obtained a grant of town land adjacent to Memorial Park for the site of their new legion hall.[4]

On the move, photo, 1947. One of the buildings of Camp Niagara is being moved off site.

Courtesy of the St. Catharines Museum, the St. Catharines Standard Collection, S1947.53.16.1.

Coming down, photo, 1947. One of the buildings of Camp Niagara is being dismantled after the Second World War.

Courtesy of the St. Catharines Museum, the St .Catharines Standard Collection, S1947.53.16.2.

After a short hiatus, summer militia camps resumed in 1952 on the Commons under canvas. Camps usually lasted one week only. Many soldiers happily returned year after year. Although some militiamen and women still arrived at Niagara on the SS Cayuga, by train, or even chartered bus, most now came to camp in truck convoys, often towing artillery hardware behind. “Despatch riders” or DRs, who usually were veteran sergeants, often led such convoys on Harley Davidson motorcycles.[5] Arriving at the main gate, the campers were “told off” into platoons and then quick marched proudly into camp, led by a bugle, trumpet, or pipe band.[6]

One officer recalled:

In camps of those days, with Queen’s Parade running almost north and south of you, envisage … On the east side of the road would be the main Orderly Room which was a large marquee and on the west side of the road you’d start with the officers’ tents, then there were some QM tents if I recall correctly, then the bell tents for the enlisted men, and down at the other end were the Sergeants’ tents and various messes in each unit, so there was a whole series of unit lines running at right angles to the Queen’s Parade. And there were common showers, I just forget exactly where they were but I can recall them being set up in big marquee tents. And the latrines were old wooden types which were dragged there, brought there by truck and then dragged into position.… the female camp in those days was up against Butler’s Barracks, just to the rear of the barracks. The Canadian Women’s Army Corps usually occupied that, and that was their tented area.[7]

All training exercises during these summer camps were held at the Lakeshore Road site. Once again, every morning during summer camp, townsfolk would hear the soldiers with their marching bands parade out John or Mary Streets to Lakeshore Road. Just west of Shakespeare Street on the lake side were the rifle ranges, and further west (what is now the sewage lagoon area) was a rocket launcher range to practise lobbing blank shells out over the lake; the “stay away flag” was raised and sentries had to be placed on the lakeshore to watch for unsuspecting boats or stragglers out wandering along the beaches. Also on site was a steel Quonset hut covered with sod, towards which artillery would be fired. Officers inside would soon learn to detect the type and direction of incoming fire.[8] An old barn from the Great War period served as daytime mess hall and for storage. (Having survived decades of army use, it suspiciously burned down early in the twenty-first century.)

Challenging training courses in the driving of military trucks, Bren gun carriers, and tracked personnel carriers, including four Sherman tanks, were all carried out on military property south of the Lakeshore Road. Today this land is a peaceful parkette and cemetery. Although the Lakeshore Road training area was considered very tight, the site provided a good opportunity for the trainees to gain some experience with various weaponry and armoured vehicles.[9]

Competitions within the regiment and against other regiments were always popular events, as were the “end of camp” parties … one of which ended abruptly when a Sherman tank was driven over the embankment into the lake twenty-five feet below! Another camp tradition involved someone on a white horse, requisitioned from the local bakery or dairy, riding through camp as King William of Orange on the “Glorious 12th” of July[10] — an anachronism of old protestant Ontario.

Niagara has always been known for its voracious mosquito population. In the 1950s DDT spraying in camp was carried out by an outside contractor using fogging trucks, which would drive up and down the lines spraying the pesticides, usually when the troops were away. However, on at least one memorable occasion when a certain officer was still in the latrine, the sprayer’s nozzle “sort of” hit the bottom of the latrine’s door and “the door exploded open and out he came clutching his trousers and shaking his fist.”[11] On other occasions the fogging truck would stall just outside the officers’ mess. Herbicides were also sprayed particularly near Paradise Grove.

Other groups also used Camp Niagara during the summer — instructors and teachers of Army Cadet Programs attended camp. Wolf Cubs and Boy Scouts held nature treks on the Commons. In 1955 the 8th World Boy Scout Jamboree was held there (see chapter 19).

The last public function at Camp Niagara was the wedding reception for Warrant Officer Bill Bowman’s daughter Gail and the young groundskeeper/fogger Mike Dietsch.[12] The Lincoln and Welland’s sergeant’s mess, on the upper floor of the two-storey Butler’s Barracks,[13] was the venue for the festivities.

With the advent of the Cold War and proliferation of nuclear weapons, militia training in Canada radically changed direction. In the event of a nuclear war there would be limited need for conventional weaponry, hence, a new emphasis on “National Survival” and civil defence. Men and women of the militia now received specialized training in first aid, search, and rescue, particularly with regards to controlled entry into “bombed out” urban areas. A “survival village” was constructed at the rifle range to simulate a series of partially destroyed buildings so that the militiamen could practise their skills.

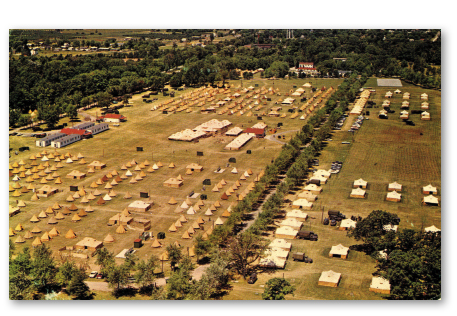

Canadian Army Training Camp, postcard, 1950s. In the 1950s Camp Niagara was still a popular venue for summer militia camps and other groups.

Peterborough Post Card © H.R. Oakman, author’s collection.

In 1964 the Minister of Defence released a White Paper calling for the militia to be the “back up” for the regular army and align their training with that of the regular forces. Regiments were disbanded or amalgamated with nearby regiments. A total of seventy-two militia units were disbanded across the country.[14]

The 1964 Camp Niagara consisted of officers only with specialized training in tactical manoeuvres. Finally, in 1966 Camp Niagara was officially closed after ninety-five years of military training. However, in April 1968 the Lincoln and Welland Regiment held a three-day “Exercise Lincoln Green” inside Fort George — the first time that the fort had been officially occupied by a military unit in more than 150 years.[15] Small weekend camps were held at the Lakeshore Road site well into the 1970s. Finally in 1969 the jurisdiction of the site was officially transferred from DND to Parks Canada. The Fort George Military Reserve was now truly a commons.

Camp Niagara was never a large, important military base like Valcartier, Petawawa, or Borden. However, because of its compact size, picturesque location, and the strong military heritage of the site, Camp Niagara was always the favourite destination of the men and women trainees. As one commanding officer noted, “You could go down there for a week and do your training and you’d come back feeling that you belonged to something important. And that’s the essence of a militia camp.”[16]

Many years later a memorial cairn was erected on the Commons with the inscription:

THEY WILL NEVER KNOW THE BEAUTY OF THIS PLACE, SEE THE SEASONS CHANGE, ENJOY NATURE’S CHORUS. ALL WE ENJOY WE OWE TO THEM, MEN AND WOMEN WHO LIE BURIED IN THE EARTH OF FOREIGN LAND AND IN THE SEVEN SEAS. DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF CANADIANS WHO DIED OVERSEAS IN THE SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY AND SO PRESERVED OUR HERITAGE.