Chapter 18

By Water and By Rail

Camp Niagara was a successful military camp in part because of its ready railway access and the introduction of large trans-lake passenger steamships.

By Water

Indigenous peoples plied the waters of Lake Ontario in their bark canoes long before the French introduced sailing vessels as they expanded west of the St. Lawrence Valley. In the early 1700s the isolated and struggling Fort Niagara at the mouth of the Niagara River was completely dependent on sailing ships supplying provisions, ammunition, and military reinforcements, as well as shipping out valuable beaver pelts harvested in North America’s hinterland. With the defeat of the French in the Seven Years’ War and a verbal treaty with the Seneca nation, the British established Navy Hall on the west bank of the Niagara River. Thanks to a ready supply of oak trees, a hastily constructed shipyard was soon busy repairing and building new vessels for the Provincial Marine.[1] By the time Niagara was the capital of Upper Canada, most of the ships on Lake Ontario were operated by the Provincial Marine, transporting military and civilian personnel as well as various trade goods; a few cargo ships were owned by enterprising merchants.[2] During the War of 1812 the American capture of York and Niagara was accomplished by amphibious invasions from the lake; although, for most of the war the British and American navies chased one another about the lake without any actual naval engagement.[3]

After the war the Rush-Bagot Agreement of 1817 severely curtailed naval activity on Lake Ontario. However, commercial traffic on the lake quickly revived. Sailing vessels, mostly schooners, continued to ply the waters of Lake Ontario, but the 1816 launch of the Frontenac, the first steamship on the lake, signalled a new era in passenger transportation. Queenston-born John Hamilton[4] and several competitors built and operated increasingly larger and more efficient steamships, which offered regular comfortable passenger service between the growing communities of Niagara, York, Kingston, and Prescott.[5]

In addition to their regular runs, steamships would occasionally be called upon for special duty. On a cold December day in 1837 locals were surprised to see the steamship Transit, which they knew had already been laid up for winter in Toronto, approaching Niagara. With news that Mackenzie’s rebellion had broken out in Toronto, 250 men of the local militia were called out and left immediately aboard the Transit.[6] Another steamer, the Britannica, also set out with great fanfare with one hundred volunteers of militia troopers plus twenty horses aboard, only to be turned back by a violent storm.[7]

Fort Niagara, photo, Cosmo Condina, 2011. For nearly three hundred years the “French Castle” has stood guard at the mouth of the Niagara River.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Five years earlier the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company (NHDC) had been formed at Niagara. It drained and reclaimed forty acres of marshland and became a major ship building concern on the waterfront (see chapter 21). By the 1850s, however, the steamship companies were confronted by growing competition for passengers and freight from the emerging railways. Local businessman Samuel Zimmerman purchased the assets of the bankrupt NHDC and extended the railway to Niagara in an effort to coordinate the schedules of the two modes of transportation and attract more customers. After Zimmerman’s untimely death, Captain Duncan Milloy[8] gained control of the Niagara dock from which he operated his City of Toronto.[9] The mercantile business in Niagara was in serious decline due to the Welland Canal and loss of the county seat. Nevertheless, the Town of Niagara continued to be a regular stopover point for the popular pilgrimage-like excursions from Toronto to Queenston and the battlefield of Queenston Heights. One commentator described the excitement and anticipation of the visit of HRH Edward, the Prince of Wales to the new Brock’s Monument in September 1860:

TOP: Rail Road and Steamers, advertisement, circa 1854. Entrepreneur Samuel Zimmerman coordinated the schedule of his Erie and Ontario Railroad with trans-lake steamers, thus making Niagara an important transportation hub.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #988.5.208.

BOTTOM: Rail Road and Steamship ticket, paper, circa 1860. This is part of a ticket for one passage from the Suspension Bridge station at Niagara Falls to the Town of Niagara via the Erie & Ontario Rail Road and then by the Steamship Zimmerman to Toronto.

Courtesy of Roger Harrison.

… the steamer Peerless left Toronto at the early hour of five o’clock, yet with 500 passengers, a motley gathering of civil and military, volunteer rifles, a Highland company, Yorkville cavalry and many veterans of 1812, dressed many of them in the uniforms of their times. Rival pipers appeared and in the language of the newspaper account of the day the air seemed alive with the shrillest and most maddening music that ever was invented. At Port Dalhousie a company of St. Catharines Rifles joined them with a band, and at Niagara another addition was made and on nearing Queenston it was seen that the heights were dark with people.[10]

And after the speeches and unveilings the Prince embarked on the Zimmerman under Captain Milloy for Niagara, where:

… a handsome arch had been erected and also a pavilion on the wharf. A band of pretty little girls strewed flowers before the Prince and school children sang God Save the Queen … and the Mayor read the address …[11]

One of the prime reasons for choosing the old Military Reserve at Niagara as a site for annual summer camps for militia was its ready access to water transportation. Thousands of soldiers with all their equipment would have to be transported back and forth from Toronto. The Milloy family’s lone passenger ship could not meet the need, and so the Niagara Navigation Company (NNC) emerged.

The first boat in its fleet was the Chicora, the “Land of Flowers.” Built in England, she initially served as a successful Confederate blockade runner into Charleston, South Carolina. With the American Civil War over, she was cut in half to pass through the canals into the Great Lakes. Reassembled, this 210-foot side-wheeler transported troops for the Red River Expedition during the first Riel Rebellion in Manitoba, 1869–1870. Purchased by the NNC in 1878, the Chicora spent its last forty years on the more peaceful Lake Ontario run.[12] Initially the NNC was refused landing rights at the Niagara Dock and ran from Toronto to Lewiston/Queenston. Responding to demand, a second boat, the Cibola, was added to the fleet, followed by her sister ship, the Chippewa,[13] described as a floating palace with a 192-foot salon. By then the ships were allowed to dock at Niagara. When the Cibola burned at her berth in Lewiston in 1895 she was replaced by the Corona the following year. At the turn of the century, all three ships of the NNC’s fleet — all their ships’ names began with C and ended in an A — operated on the Toronto-Niagara run and offered six round-trips a day with a full load of passengers and freight.[14]

The Pan American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901 popularized the water and rail route between Toronto and Buffalo. In response, the Cayuga was launched in Toronto in 1906. At 317-feet long and capable of carrying 2,500 passengers, she was the largest passenger ship on the lake. A few automobiles could also be transported on the lower deck. Over the next half-century she would carry over 15 million passengers.

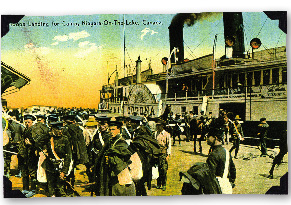

For the young soldiers travelling from the Toronto area to Camp Niagara, the boat ride aboard one of these steamships was a much-anticipated bonus. The various regiments would either march or travel by train or streetcar to the docks at the foot of Yonge Street. There would be much commotion — up to two thousand men with their officers barking out commands, as well as their baggage, supplies, cavalry horses, and even ordnance, would have to be loaded aboard before embarking. Once underway a military band or lone piper would often entertain the soldiers and any civilian passengers during the two-hour trip.[15]

It was not always a warm, sunny day with clear sailing on a placid lake. One young cadet on his first trip away from home recalled spending the night before sailing with some pals indulging in numerous banana splits. Aboard one of the side wheelers the next day, “the heaviest storm in many years” struck. “[We] arrived at Niagara a very, very sick bunch of boys. Boy, it was really something.”[16] An easterly wind caused many a soldier to lose his breakfast sailing across Lake Ontario.

SS Chippewa, photo, circa 1910. The steamer Chippewa was described as a “floating palace.”

Courtesy of Pat Simon and Joe Solomon.

As the Cayuga approached the mouth of the Niagara River, a loud blast of her steam whistle would announce her imminent arrival. In summer months during the slow disembarkation process on the docks, young boys would dive for silver coins thrown by soldiers or tourists who lined the boat’s rail.[17]

Once back on terra firma, the regiments would form up. Then, with flags and banners flying, they marched up King Street, often taking a circuitous route towards Camp Niagara led by bands playing rousing regimental music. It often seemed as if the whole town had turned out to welcome them, enthusiastically crowding the dock and lining the streets. Meanwhile, with another blast of the horn, the ship would gradually pull away from the dock[18] and head up to Queenston and then over to Lewiston, often to take on fuel before turning down river and making another stop at the town dock.

Troops Disembarking for Niagara Camp, postcard, circa 1910.

Courtesy of the author.

TOP RIGHT: Troops Landing for Camp, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada, postcard, circa 1912.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

CENTRE: Troops Leaving Niagara-on-the-Lake for the Front, postcard, 1915. A time of emotional farewells as many of the boys would never return home.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

<

<

BOTTOM RIGHT: Are We Down-Hearted? No!, photo postcard, 1915. Soldiers leaving Camp Niagara aboard steamer with contented mascot.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

During the war years when departing soldiers were re-embarking ships for Toronto and deployment overseas, there were many emotional and heart-rending sendoffs as the steamer gradually pulled away from the dock. For many of these boys Camp Niagara would be their last meaningful life experience in Canada.

Quite aside from Camp Niagara’s dependence on water transportation, the steamships, and in particular the Cayuga, held a special place in the social fabric of the town. The Cayuga always made her first trip of the season around May 24 with a boatload of people from Toronto. All the local school children and a few parents would then be treated to a free boat ride aboard the Cayuga up the Niagara River and back. Kaye Toye recalled the excitement of the day:

This was the day long anticipated by every child.… Long before it was time to see the boat rounding Fort Niagara, we were all at the dock, standing tiptoe, breathless with expectancy. Finally the shout went up, “We see her, we see her! Look at the Union Jack flying atop the centre spar!”[19]

As another citizen remarked years later, “It was just the greatest thing.”[20]

Throughout the summer season, the boats were so regular that golfers on the Mississauga links knew the time simply by the steam whistles of arriving or departing ships. With up to three round trips a day, thousands of tourists arrived daily to visit the town or proceed up to Queenston Heights for group picnics or connect by train to Niagara Falls and Buffalo. Some of these were family and friends visiting the soldiers on Sundays. During the summer local fruit growers shipped fresh tender fruit to ready markets in Toronto. For two special weeks in August 1955, international campers and visitors crowded the Cayuga during the 8th World Boy Scout Jamboree (see chapter 19). For the local citizens and servicemen on leave, the ships offered an easy and cheap opportunity to “escape” to Toronto.[21] For several generations of young people and the young at heart, the midnight cruises with live bands and lots of refreshments were indeed memorable. Some of these cruises crossed the lake to Toronto, returning in the wee hours of the morning.

The Cayuga was the last of the great steamships on Lake Ontario.[22] With the popularity of the automobile, and in particular the easy access of the Queen Elizabeth Way, the passenger lists dwindled, and after a few half-hearted attempts to revive the service, the Cayuga made its final crossing in 1957. There have been several varied attempts to revive regular cross-lake passenger service, but so far none has survived.

By Rail

The first railway in the province had been established tantalizingly near Niagara. The Erie and Ontario Railroad was chartered in 1835, running between Queenston and the Welland River; shortly thereafter it was extended to Chippawa on the Niagara River. It ran on wooden rails covered with iron, and the cars were pulled by up to three horses in tandem, so it was really a horse-operated tramway. Although it coordinated its schedule with a steamship at Queenston, it could not compete with the Welland Canal and soon fell into disuse.

Queen Street Station, M.C.R.R., Niagara-on-the-Lake, postcard, published by F.H. Leslie, circa 1912. The Michigan Central train chugs northward across the intersection of King and Queen Streets. Note on the left the Hotel Niagara, now The Prince of Wales Hotel, situated on land that was originally part of the Military Reserve/Commons and the great swap.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2009.030.001.

The entrepreneurs of the province were slow to catch the “railway fever” that was gripping the United States. However, in 1853 the enterprising Samuel Zimmerman[23] purchased the assets of Niagara’s bankrupt Niagara Harbour and Dock Company, and with the thought of producing locomotives and railway cars at the Company’s foundry, he revised the Erie and Ontario’s charter. The track was upgraded to carry steam engines and it followed a new easier grade down the escarpment near St. Davids and travelled beside Concession 1 (later called Railroad Street) to East-to-West Line. Here it split with the main line cutting across country to the corner of John and King Streets. It then followed along the east side of King Street down to Ricardo Street where it then turned down towards the dock area after crossing over Delater Street on a high trestle. A stone turn table[24] allowed for the engine to turn 180 degrees for the trip back up. At King and John Streets a collateral branch followed along John Street East. This line met the spur line that traversed John Street East and passed through Paradise Grove along a trench, “the cutting” twenty feet deep and eighty feet wide ending near present Navy Hall.[25]

Although the new railway did not save the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company it was a financial godsend for the town and ultimately made Camp Niagara possible. The local newspaper, The Niagara Mail, writing in the midst of the Crimean War, heralded the dawn of the railway era in town and compared the train’s raucous steam whistle to “a scream like a Russian’s, in the hands of a Connaught Ranger.”[26] Eventually the railway was extended to Fort Erie and by railway bridge across the Niagara River to Buffalo. Passengers from Toronto could travel by steamship to Niagara and then take the train all the way to Niagara Falls or Buffalo. With connections at St. Davids and the Suspension Bridge station in the Falls, one could connect with railways all over southern Ontario, as well as Michigan and New York States. Conversely, soldiers from all over southern Ontario (and later Buffalo) could be transported into and out of camp in long trains along with their baggage, supplies, horses, and ordnance. There was even a Red Cross train set up as a hospital to transport seriously ill or wounded men out of camp to military hospitals. In the balmy days of this railway there were six passenger trains using the line daily,[27] and extra trains were added to meet the needs of the army. The men usually detrained along John Street East where there was a siding spur, thus accommodating two trains at the same time. On occasion the men detrained along King Street. The officers had their own train stop. Many friends and family members would also come by train, usually on Sundays, to visit their loved ones in camp. Military tattoos performing with precision on the Military Reserve also attracted paying customers. The same railway was used during the annual migration of wealthy Americans to their summer homes in Niagara as well as affluent visitors to the Queen’s Royal Hotel. The many visitors to Chautauqua Park often arrived by train.

Soldiers boarding a train, circa 1917. Soldiers are boarding a train on railroad spur-line along John Street East at Charlotte Street. Note the cement bridge over One Mile Creek at the left.

Courtesy of Jim Smith.

The railway line went through several name changes and ownership.[28] In an effort to keep the line viable, the town and township were on occasion called upon to purchase shares or advance funds to the railway to ensure its continued operation.[29] Nevertheless, as with the steamships, the railway eventually fell victim to asphalt highways. The last train chugged out of Niagara in 1959.[30]

Niagara Central Ry. Cars Leaving Simcoe Park, photo, circa 1920. A crowded electric streetcar is about to cross the King and Queen intersection.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2000.012.

For a period there was also an electric railway line coming into Niagara from St. Catharines. With both freight and passenger service, “the car” was used primarily by the locals on shopping expeditions and by some students attending schools in St. Catharines. Soldiers on leave could hop on the trolley to “escape” to the city. The line entered town near Mississauga and John Streets, travelled along John Street and then ran down King Street. The original station on King Street at Market Street still stands today. The electric power was turned off in 1931.