Chapter 19

Special Events on the Commons

The Funeral of Sir Isaac Brock and the Condolence Ceremony

Perhaps the most sombre events ever recorded on the Commons were the funeral of Major General Sir Isaac Brock and his provincial aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell, on October 16, 1812, and the Natives’ Condolence Ceremony one month later.

Major General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B. (1769–1812), miniature pastel attributed to Gerrit Schipper (as part of research by Guy St.Denis), circa 1809–10. Brock’s energetic efforts to organize the militia prior to the war and his audacious capture of Fort Detroit emboldened the combined British forces as well as the population of the Province. His death at Queenston Heights created an enduring symbol of patriotism in Upper Canada. This is the only authenticated portrait of Brock as an adult approaching middle age. At the time of his sitting Brock was a brigadier general on the staff of Sir James H. Craig.

Courtesy of the Guernsey Museums and Galleries, GMAG 2009.52.

It fell upon Captain John Glegg to make the funeral arrangements. Brock’s body was laid in state on October 14 in Government House, the former home of D.W. Smith (see chapter 21) facing the Commons. Soon he was joined by young Macdonell, who had suffered a slow and agonizing death. On October 16 the funeral procession got underway, with detachments from the regular army, militia, and Indian Department lining each side of the route from Government House across the Commons to Fort George. All officers were required to wear black armbands and black crepe on their sword knots during the funeral and for one month afterwards. During the procession, the Royal Artillery fired minute guns with two nine-pounders. Fort Major Campbell led the procession, followed by a company of the 41st Regiment and a company of militiamen. Next came the band of the 41st playing a dirge, its drums muffled and draped in black cloth. Four grooms led Brock’s horse draped in ornamental coverings, after which came three groups: the general’s personal servants, four surgeons, and Fort George’s chaplain, the Reverend Robert Addison.

A team of horses drew the first caisson bearing the casket containing the body of Macdonell, attended by six pallbearers and three mourners, foremost of whom was his brother Alexander Macdonell. Brock’s caisson followed, accompanied by nine pallbearers and several chief mourners, including Major General Sheaffe. Staff from the provincial government, civilian friends, and the general public followed behind.

After Reverend Addison read the service the two caskets were lowered into a single grave dug in the cavalier York bastion (known thereafter as the Brock bastion). At that point a twenty-one-gun salute was fired in three salvoes of seven guns each. (This was echoed by a similar salute from Fort Niagara whose flag was at half-mast.[1] ) A twenty-four-pound cannon captured at Detroit was placed at Brock’s head.[2] “A more solemn and affecting spectacle”[3] had never before been witnessed by the thousands of spectators present that day.

Three weeks later a Native Council of Condolence ceremony was performed at the Indian Council House on the Commons. Present were members of the Six Nations, Hurons, Chippewas, and Potawatomies, among others. Representatives of the Indian Department included William Claus, Captain John Norton, and Captain John Baptiste Rousseaux. Chief Little Cayuga was the chief speaker who presented eight strings of wampum and declared:

… now seeing you darkened with grief, your eyes dim with tears and your throat stopped with the force of your affliction, with these strings of wampum we wipe away your tears, that you may view clearly the surrounding objects. We clear the passage in your throats that you may have free utterance for your thoughts.…[4]

He then explained that he was presenting a large white belt of wampum to be placed over Brock’s body to protect his remains from injury[5] and grant him a happy afterlife. Finally, on addressing Brock’s successor, Major General Sheaffe, he pledged the Natives’ confidence and continued support for his leadership.

Second Funeral for Brock and Macdonell

Twelve years later thousands more gathered on the Commons on a “remarkably fine”[6] October morning to witness a similar ceremony. A Tuscan-style column had been erected at Queenston Heights as a permanent memorial and final resting place for Brock and Macdonell. In a solemn ceremony, the remains of the two were removed from the Brock bastion of Fort George (which was already in a state of ruin) and transferred to a black hearse drawn by four black horses, each with its own leader. To the sound of sombre band music and a nineteen-gun salute, the cortege slowly made its way across the Commons, followed by a procession of military officials, chiefs of the Six Nations, and civilian dignitaries, with common folk falling in behind. The procession to Queenston Heights took three hours and ended with the remains being deposited in a crypt in the base of the column. Poor Brock and Macdonell would be reburied twice again.[7]

Provincial Agricultural Fair

When the first Agricultural Society in Upper Canada was formed in Niagara in 1792, one of their first acts was to encourage an annual fall fair as a celebration of the bountiful harvest. The Niagara Fair continued annually for at least 150 years and was held in various locations. However, in September 1850, with financial assistance from the town, the Provincial Agricultural Exhibition was held on fourteen acres of the Commons demarcated with a “substantial octagonal fence. The Floral Hall was 140’ X 42’, Agriculturists’ Hall and Mechanics’ Hall, each 100 X 24’.”[8] A grandstand and half-mile racetrack were other features. Events included a ploughing match, presumably on the turf of the Commons. Some indoor exhibits and lectures were also held in the court house. In a predominantly rural province, this was a very important event at the time, even attended by the Governor General. The exhibition buildings apparently were soon taken down and the grandstand was accidentally burned by Camp Niagara trainees during the Great War. Nevertheless, fall fairs including horse racing continued at this site until the building of the senior citizens’ apartments and the Carnochan subdivision in the mid-twentieth century.

The Day of the Tornado

One of the greatest recorded natural events to hit the area was a tornado that swept in from the northeast off of Lake Ontario early in the morning of April 18, 1855. First to be hit were several buildings of the recently built Niagara Car Works at the waterfront. The twister then bounced over to the park where a large “Daguerrean Saloon”[9] was flipped over two or three times, scattering its contents on the Commons. The tornado then took off the roof of St. Andrew’s church as well as the Angel Gabriel weathervane on the steeple.[10]

Loyalist Centennial Celebrations in 1884

A large proportion of the Ontario population still claimed Loyalist ancestors in the 1880s. Hence there was much interest in commemorating the centennial of the arrival of the United Empire Loyalists in 1884. Three specific events were planned. In June a three day celebration was held in Adolphustown, Prince Edward County to mark the actual arrival of the loyalists in the Bay of Quinte area. The festivities then moved on to Toronto for a day of rousing speeches and special exhibitions. On a sunny day in August, two thousand spectators gathered in a “glade in the Oak Grove” on the Commons. At one o’clock the invited dignitaries took their places on a specially built platform. Measuring thirty-six by twenty-four feet, the stage was dominated by

a large flagstaff with the Union Jack in the centre and British ensigns at each of the corners. In front was a large painting of the Royal Arms, and around the platform were festoons of oak and maple leaves. Tablets on the sides and front of the structure bore the names of the men of the Lincoln militia who fell during the War of 1812.[11]

With this patriotic backdrop various dignitaries spoke, including Lieutenant Governor John Beverley Robinson, Senator J.B Plumb, local politicians, and two chiefs of the Six Nations who led a delegation of forty-eight chiefs from the Grand River Reserve (two of whom were in their nineties and had fought in the War of 1812). Chief A.G. Smith concluded his remarks with, “I firmly believe that the day is not far distant when the Indians will be able to take their stand among the whites on equal footing.”[12] The program finished with five aged chiefs of the Cayuga and Onondaga nations, in their traditional dress, performing a traditional war dance followed by three rousing cheers for the queen.

Ribbon for the centennial of the landing of the Loyalists, textile, 1884. Each Loyalist attendee of the centennial celebrations on the Commons was issued a Red Ribbon to wear proudly.

Courtesy of Gail Woodruff.

Centennial of the First Parliament of Upper Canada

To celebrate the Province of Ontario’s one hundredth birthday in 1892, the government of Ontario provided $2,000 towards the cost of two successive celebrations held in Niagara and Toronto. Recognizing that Niagara was the first capital of Upper Canada, the celebration on July 16 would commemorate the date on which the proclamation was issued, summoning elected members to the first parliament. Most of the dignitaries arrived by steamer and were escorted by marching bands through the gaily decorated town[13] to the Commons near the ruins of Fort George, where they were joined by a large crowd of locals. After the Lieutenant Governor read the original Proclamation there followed a royal salute of twenty-one guns by the Welland Field Battery. After a long rambling speech by the vice-regal representative, Canon Bull read prayers from Captain Joseph Brant’s prayer book. Dignitaries and guests then “partook of luncheon at the Queen’s Royal Hotel.”[14] The party reconvened in what is now Simcoe Park at four o’clock when the premier of the province, Sir Oliver Mowat,[15] reviewed the history of Canada and spoke glowingly of the bright future for Canada as an independent country. The program concluded with short addresses by other politicians and the singing of patriotic songs. Although there is no reference in the official program, it appears that an exhibition game of lacrosse was held probably on the Commons sometime during the day, as there is an item in the statement of expenses for Niagara of $41 for “Lacrosse Match.” A memorial water-drinking foundation was commissioned and this still stands on Queen Street today. A medal to commemorate the centennial celebrations was struck and widely distributed.

On September 17, 1892, the actual anniversary of the opening of the first parliament, an extensive program was held in front of the new provincial parliament buildings at Queen’s Park in Toronto.

These various centennial celebrations were much appreciated at the time and their memories lingered. They fostered an enthusiastic interest in local history that culminated in the formation of several historical societies which have survived to this day.

On September 17, 1992, a re-enactment of the first parliament was held in a sunny Simcoe Park, Niagara-on-the-Lake, with Premier Bob Rae and most of the members of the provincial parliament in attendance. A reception followed in restored Navy Hall.

Bonfires on the Commons

Periodically, bonfires on the Commons have signalled to the townspeople something of great import. The progress of the Crimean War, 1853–1856, had been followed with great interest in Canada. When news arrived that the British had taken Sebastopol, “[a]n immense bonfire was made on the common, a whole ox was roasted, and with bread and ale ad libitum a memorable feast was held in honour of the victory.”[16] There was singing, dancing, and firing of cannon till morning.[17]

The World Boy Scout Jamboree

It was an inauspicious start. Hurricane Connie swept in off Lake Ontario with high winds and driving rain flattening the large canteen tent that measured one hundred feet by four hundred feet as well as several smaller marquees and bell tents. They had already been set up in anticipation of the Jamboree set to start five days later, but with the help of hundreds of volunteers the damage was rectified. The next day dawned bright and clear.

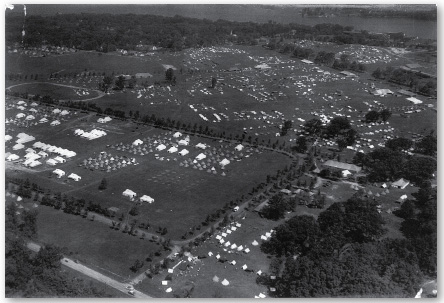

Air photo of the Jamboree, photo, 1955. Looking northward across the Commons. A small portion of John Street East can be seen in the lower left-hand corner.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2000.007.

The 8th World Boy Scout Jamboree was the first to be held outside Europe.[18] The title “Jamboree” is derived from an American Native word meaning “a joyful meeting of the tribes” — certainly appropriate for this huge international gathering of scouts on the Commons during a hot August 1955. In the decades following the Second World War, Scouting was immensely popular. By the mid-1950s Lord Baden-Powell’s troop of young men was six million strong and it was estimated that at least thirty million young men around the world had spent at least part of their youth in scouts. In 1955 Niagara-on-the-Lake was a very quiet, sleepy town. The mayor of Niagara-on-the-Lake, William Greaves, in his welcoming address admitted that he doubted if the town had ever been as excited since the War of 1812 as it was about the Jamboree. For ten days the Commons would be alive with 11,000 campers and 250,000 spectators who paid 25 cents to enter the campsite.[19]

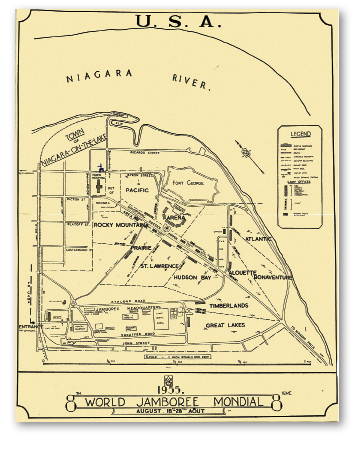

Plan of the Jamboree, paper, 1955. This plan shows the locations of the various sub-camps and the administrative buildings.

Courtesy of the author.

The happy campers from sixty different “free nations”[20] started arriving by boat, train, bus, and bicycle[21] on Thursday, August 18. Probably the scout with the shortest distance to travel was Steven Scott, who lived on King Street.[22] Much of the Commons to the south and west of Queen’s Parade was divided up into various sub-camps with distinctly North American names such as Alouette, Timberlands, Hudson Bay, Great Lakes, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific. Two of the sub-camps were actually in part of Paradise Grove, which had been chemically cleared of poison ivy. Each country’s delegation was assigned to one of these sub-camps. Most of the countries then created their own unique “gateways” to their campsite. In the section between Queen’s Parade and Fort George a huge arena was built on the grassy turf. A tiered three-sided grandstand seating 10,000 was built facing a 3,250-square-foot canopied stage, with a large deep-blue backdrop and Fort George’s palisades beyond. A mammoth floral replica of the First Class Scout Badge using 5,500 plants[23] and the Flag Plaza were in front of the arena. Scattered throughout were canteens, showers, and toilets; along Queen’s Parade were more canteens, a camp post office, bank, and trading posts.

Aerial view of the grandstand, photo, 1955. The tiered grandstand could seat 10,000 spectators with space for a similar number within the inner circle. The temporary facility was located between Queen’s Parade and the restored Fort George.

Courtesy of the St. Catharines Musem, the St. Catharines Standard Collection, S1955.12.6.1.

In the rectangle between Sheaffe and Athlone Roads were the Jamboree headquarters, which included facilities for all the support staff. There a media tent serviced three hundred reporters, photographers, and technicians. The CBC transmitted live coverage of the Jamboree to its listeners and viewers by means of a ninety-foot tower erected for the purpose. The American CBS television network also covered the event.

The Jamboree hospital was set up by the Tri-Services Staff of the Department of National Defence in Parliament Oak School opposite the Commons. A ward of 102 beds was created in the school while tents were pitched on the school grounds for the staff. Before the end of the Jamboree, there were nearly six hundred visits and over two hundred admissions to the hospital. At least two patients were referred for appendectomies, and one photo-journalist died when he fell off one of the camp’s media towers.[24]

The Niagara Parks Commission planted extensive floral gardens at the entrances to the camp as well as the previously described huge raised bed at the Flag Plaza.

The opening ceremonies for the 8th World Jamboree — with the slogan “New Horizons” — were held in the arena in blistering heat on the afternoon of Saturday, August 20. The chief scout and Governor General for Canada, the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, was escorted into the camp by motorcycle cavalcade, where he was welcomed by fellow Canadian Mr. Jackson Dodds, Jamboree camp chief. Also present was Olave, Lady Baden-Powell, widow of the founder of Scouting. After a short speech, the chief scout declared the Jamboree open, followed by a five gun salute from Fort George. He then reviewed the mile-long parade of countries in alphabetical order, each preceded by their flag and a plaque bearing the country’s name carried by two Canadian scouts … much like other stirring march pasts seen at international sports meets. Within the large French delegation of marchers was a group of twelve blind campers.

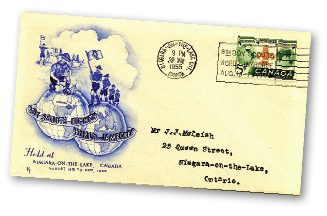

TOP: First day cover, August 20, 1955.

Courtesy of the author.

BOTTOM: Badge, textile, 1955. This badge was presented to each attendee of the 8th World Boy Scout Jamboree.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2005.002.001.

The international importance of the day was recognized by the issuing of a commemorative stamp by the Canadian Post Office with first-day covers originating at the camp’s own post office — 150,000 stamps were sold the first day.

On Sunday morning the campers dispersed to various places of worship. The Roman Catholic Church had erected an impressive chapel on the Commons to the east of the arena where two cardinals[25] celebrated Holy Mass. Three thousands scouts lined up outside St. Mark’s Church while large numbers attended other church services in town. Non-denominational services were also held in the open arena. In the afternoon the town was open to the scouts: no admission fees at the museum, no golf fees, exhibition baseball games, water skiing, and boat races at the docks. Some lucky campers were invited into private homes for refreshments.

Over the next week the scouts were kept busy learning new skills and maintaining their own campsites, but also visiting other campers, swapping various articles, and trying to keep cool with scheduled swims on Niagara’s beaches. Pick-up games of baseball, lacrosse, and cricket were common, as well as music jam sessions. One surprised American camper found a five-pound cannon ball when placing a dining table in the turf. There was a schedule of concerts performed in the arena, and each evening several countries would perform pageants portraying their history and culture. Understandably, the largest pageant was performed by the large Canadian contingent[26] portraying the rich history of Canada. On three occasions the scout troops from Toronto performed a pageant inside Fort George portraying the King’s Colours being presented to the Guards regiment by “Brock.” Most of these events were open to the general public.

All interested campers were driven by chartered buses to experience the various tourist sites in the Niagara Peninsula. On the Friday, using five trains and the steamer, Cayuga, nine thousand scouts were transported to the CNE where they performed a march past for an enthusiastic Toronto audience.

An emotional closing service was held in the arena on Saturday afternoon with a final concert in the evening.

On Sunday, August 28, it was time to make those final strategic swaps, exchange addresses, pack up, and start for home. Soon all 7,500 tents and other temporary buildings would be gone — only the packed down turf would bear witness to the fact that something glorious had just happened on this common land.

Fifty years later, a two-day reunion was held of former campers of the 8th World Boy Scout Jamboree on September 16–17, 2005. A reception and meet-and-greet was held at Navy Hall on the Friday evening. The following morning a plaque was unveiled near Butler’s Barracks[27] commemorating the Jamboree, and in the afternoon a memorial oak tree was planted by the Niagara Parks Commission on the edge of Paradise Grove. A celebration banquet followed in the evening. This reunion was held on the same weekend as the annual Scout’s Brigade. This encampment on the Commons has been held now for over ten years and usually attracts two- to three-thousand scouts from Ontario and New York State. A march through town in period costume and a re-enactment of a War of 1812 battle provide a valuable experience in living history for these young people. It also adds a little extra colour to the Commons in September.[28]

Outdoor Concerts

The Fort George Military Reserve/Commons has witnessed many military tattoos, concerts, and outdoor (drumhead) church services, often attracting thousands of participants and spectators. Moreover, concerts and pageants were performed in the ten-thousand-seat temporary grandstand during the Jamboree in 1955, and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture has been performed in Fort George.

As this book was going to press, it was announced by the AEG Live production company that on June 30, 2012, the iconic Canadian band the Tragically Hip would be headlining a massive outdoor concert on the grassy rectangle portion of the Commons along John Street. Parks Canada has reassured concerned citizens that the natural and cultural integrity of the historic site will be carefully protected. If well received, similar concerts may be entertained.

Royal Visits

The lands that were once part of the original Military Reserve have been honoured with several Royal Visits. His Royal Highness Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, visited Niagara and stayed in Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s canvas tents at Navy Hall in 1792. His grandson, His Royal Highness Edward, Prince of Wales, future King Edward VII, stopped at Niagara’s waterfront for a formal presentation from the town in 1860. His Royal Highness Prince George, Duke of Cornwall, and later King George V, and his wife visited Niagara in 1901. Their son His Royal Highness King George VI and his wife Queen Elizabeth drove around the fortifications of the partially restored Fort George in 1939. Elizabeth returned as Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother for a ceremony at Fort George to commemorate the town’s bicentennial in 1981. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh were honored at a Civic Ceremony at Fort George in 1973. His Royal Highness Prince Edward visited the Lincoln and Welland Regimental Museum in Butler’s Barracks as well as Fort George in 2003.

H.R.H. Edward Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820), artist William Bate, enamel on copper, 1810. The Simcoes reluctantly gave up their comfortable canvas habitation at Navy Hall for the prince’s accommodation during his visit to Niagara in August 1792. Edward was the father of the future Queen Victoria.

Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM, #962.32

Royal visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall 1901, photo. This photo, taken at the foot of King Street opposite the Old Bank House, shows the future King George V and his wife Mary about to board the train.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #993.067.60.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and HRH The Duke of Edinburgh inspecting War of 1812 re-enactors at Fort George, photo, 1973.

Courtesy of Pat Simon.