Chapter 20

Sports on the Commons

Equestrian Sports

Garrison towns have long been associated with horse racing, and certainly Niagara was no exception. Within one year of the commencement of construction of Fort George, there appeared in the The Upper Canada Gazette for June 27, 1797, the following announcement signed by three prominent local citizens: “Races will be run for over the new Course on the plains of Niagara. A purse of 20 guineas, 10 guineas etc.”[1] The races were run over three days in July. Shortly thereafter the Turf Club was established “to promote an intercourse of commerce, friendship and sociability between the people of this province and those of the neighboring parts of the United States.”[2]

In a letter to the editor of a local Niagara newspaper in 1801, a “Sportsman’s Friend” warns all unwary local “sons of the turf” not to be taken in by a scheming “famous jockey … capt. Skanundaigua alias Black Legs,” who was known to frequent the local “bar-room”[3]

Following the War of 1812, “matches and sweepstakes” were reintroduced over the course near Fort George. A description of one such event during the race season in 1817 confirmed that horse racing had become one of the social highlights of the year for both the military and civilian elite of the town:

The charming music of the band of the 70th Regiment was heard. The officers of the 70th gave a dinner, ball and supper to a large party in their messroom [at Butler’s Barracks]. Dancing was kept up till five in the morning.

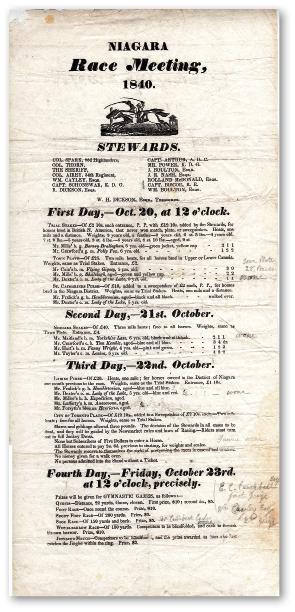

Over the next several decades the Turf Club continued to sponsor races on the Commons. An announcement for the Niagara Race Meeting in 1840 records a list of stewards including officers of the King’s Dragoon Guards, all excellent horsemen themselves. The races would be run over three days, starting at twelve o’clock. Various categories were listed for “one or two mile heets [sic]” for a host of purses and plates.[4] Spectators had the advantage of simply climbing the ramparts of old Fort George to gain a good view of the races. Someone recalled that the races could be viewed from the belvedere of the rectory of St. Mark’s. Nevertheless, the spectacle of horses and their riders charging towards the finish line could be a dangerous one. An entry in St. Mark’s Record of Burials noted, “1850 Aug. 8, Frederick Tench, died 5th Aug., in consequence of being dashed against a tree on the common near the race-course, in running a horse of Capt. Jones, aged 38.”[5] An obituary in the St. Catharines Journal in 1858 noted the death of long-time resident, Adam Crysler: “for many years a tavern keeper in Niagara, was killed on Thursday last by the falling of the grandstand at the race course. Several other persons were injured.”[6] Apparently, he was operating a refreshment stand under the spectators’ stand when it collapsed.

Turf, with Jockey Up, at Newmarket, artist George Stubbs, circa 1765. Although this remarkable image was painted in England, the broad turf and trees beyond evoke the old racecourse on the Commons.

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.621.

It appears that horse racing on the old racecourse on the Commons became less frequent as the British garrison at Niagara dwindled in size. The annual agricultural fair with its grandstand and racetrack on the edge of the Commons continued to offer horse racing well into the twentieth century.[7] The larger original racetrack in the centre of the Commons was incorporated into the golf links in 1895. A generation later, racing on the old course took on a modern twist when American summer residents would organize clandestine races of their fancy automobiles around the old track.[8]

Interestingly, even today aerial views of the commons reveal the outline of the old racetracks.

Polo is another sport brought to Niagara by various British regiments. Although not recorded, the elite King’s Dragoon Guards probably played polo on the commons turf during their stay at Niagara, 1838–1842. Long time Niagara resident Kaye Toye recalled that “summer evenings rang with the sound of the polo mallets as the Royal Canadian Dragoons galloped across the polo field by Fort George”[9] in the 1930s.

But it was not until the 1980s when a real resurgence of interest in polo on the Commons was developed as a fundraiser. First, the field between the Sheaffe and Athlone Roads had to be converted into a regulation field at considerable expense. For several years the Chamber of Commerce ran the annual event, and in 1993 it became the annual Heart Niagara Tournament.

Niagara Race Meeting 1840, paper, 1840. An announcement for a busy racing session on the Commons. Note the race session concludes on the final day with “gymnastics games” including “quoits,” a blind wheelbarrow race, and a “jingling match” with prizes.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #972.701.

Goals on the Common, one Common Gaol, paper, 1998. This was an invitation to the Annual Polo for Heart Niagara Tournament held on the Commons for several years in the 1990s. Walker Industries Holdings Limited was one of the prime sponsors of this “spectacular” fundraising event.

Courtesy of Walker Industries.

Recently dressage and steeplechase have returned to the Commons. Although well attended such activity has reportedly damaged the polo fields.

The fourth equestrian sport associated with the military is “tent pegging.” This is an ancient East-Indian sport apparently developed to improve an equestrian’s battle skills. It involves a trooper riding at full gallop across a timed course on the flat and over jumps. Armed with sword, sabre, and/or lance, the rider attempts to smite a succession of ground and elevated targets. Canadian dragoon regiments training on the Commons used elements of tent pegging to improve their riding skills.[10]

Cricket

Another popular sport in British garrison towns was the game of cricket. Newspaper advertisements indicate that there were several cricket clubs in town: in 1837 one club met in Graham’s Hotel, Dr. Lundy’s Classical School had a club, and so did the Grammar School, which was close to the Commons. The Niagara Cricket Club was meeting in the local lawyer’s office in the 1860s. Interestingly, all the clubs’ executives seem to have been civilians with no military officers listed. One local boy, T. D. Phillips, apparently became best all-round player in the Dominion.[11] Although none of the announcements indicate where the actual cricket pitches were located, an 1843 map of the Reserve[12] indicates a “Proposed Cricket Ground” at the site eventually occupied by the provincial agricultural fair. With the British regiments leaving in the 1860s and the emergent popularity of field lacrosse, interest in cricket seems to have waned. In more recent years, however, a friendly match of cricket is played annually between staff of the Shaw Festival and the Stratford Fesitval, alternating between a pitch on the Commons and Stratford.

Cricket on the Commons, photo, Cosmo Condina, circa 2010. As a British garrison town, cricket was a popular sport on the Military Reserve. This tradition continues every other year on the Commons, the locale of a friendly match of cricket between the Shaw and Stratford Festivals.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Baseball became more popular in the twentieth century. One of the first baseball diamonds in the area was on the Commons just behind the Boy Scout lodge at the present-day site of the Shaw Festival Theatre. As many as one thousand spectators would turn out for a game.[13] In the 1960s the new diamond was established as part of the Recreational Sports Park at Veterans Memorial Park (see chapter 22).

Golf

Many local golf enthusiasts are aware the Niagara-on-the-Lake golf course on the Mississauga Commons is one of North America’s oldest. Yet for a generation, a unique eighteen-hole golf course, the site of many international tournaments,[14] was situated on the Fort George Commons.

The Hunter Family on the Fort George Links, “The Thorn” hole, photo, 1887. The members of the Charles Hunter family whose large home overlooked the Mississauga Links were avid golfers. Note the three caddies.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #982.384.b.11.

J. Geale Dickson grew up in what is now Brunswick House overlooking the Commons. His grandfather, William Dickson, had been a prominent lawyer and merchant who owned much of the land along John Street East (see chapter 22).Geale had served as an officer in a British regiment in England where he had been smitten by the game of golf. He returned home in 1877, and along with friend Ingersoll Merritt,[15] laid out a few practice holes on the Commons across from his ancestral home.[16] A year later, the two enthusiasts with Charles Hunter, a Scot by birth, laid out a nine-hole golf course on the Mississauga common. We have a description of one of the first rounds of golf played by Dickson, Hunter, and four friends:

… a pony cart followed them from hole to hole, laden with every possible beverage which the human tongue could desire.[After the morning round, they lunched all afternoon, dallied over cigars,] by which time it was too late to renew the contest of the morning.[17]

Several years later Geale’s twin brother Robert Dickson also returned home, and when the Niagara Golf Club was organized in 1881 he became first captain. It is important to note that at this time there were only five golf clubs in all of North America and all were in Canada: Royal Montreal, Quebec, Toronto, Brantford, and Niagara. Although the other four clubs were established earlier, the Niagara club is the only one that still retains the original site; hence its claim as the oldest surviving links[18] in North America. In 1882 the Toronto Globe enthused that the Niagara club “bids fair to become the St. Andrews of Canada.”[19] The following year the club played host to the first interprovincial golf match held in Canada. Nevertheless over the next ten years the club struggled to survive. For the wealthy Americans who summered in Niagara, as well as a few well-connected locals, yachting, tennis, and lawn bowling were the popular forms of recreation.

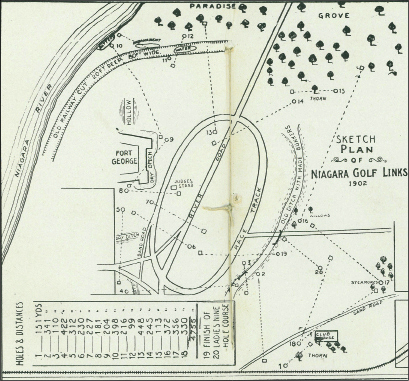

Sketch Plan of Niagara Golf Links 1902, 1902. This plan illustrates the layout for eighteen holes on the Fort George Commons. Note the club house is in the compound.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #994.208-2-large.

In the 1890s the sport of golf became fashionable in North America. Niagara, with its luxury hotel, the Queen’s Royal, became a golfing destination.

Sometime in the early 1890s Geale Dickson laid out another nine-hole course on the Fort George commons opposite his family home. In 1895 the first International Golf Tournament was held at Niagara. The first nine holes were played on the Mississauga Course and then the competitors were transported by horse-drawn conveyance to the Fort George links on the other side of town. This was not too satisfactory so in 1896 the nine-hole Fort George course was converted to eighteen while the original Mississauga Links were designated for ladies only. Both courses apparently flourished, and in 1901 the visiting Prince of Wales (future King George V) was made an honorary member of the club but regretfully didn’t have time to play a round.

Historian and golfer Janet Carnochan waxed eloquently on the uniqueness of the Fort George Links:

Surely never had the players of a game such historic surroundings. The very names of the holes are suggestive of those days when, instead of the white sphere, the leaden bullet sped on its way of death or the deadly shell burst in fragments to kill and destroy. The terms used in describing the course — Rifle Pit, Magazine, Half-Moon Battery, Fort George, Hawthorns, Oaks, Officers’ Quarters, Barracks — tell the tale.[20]

The clubhouse for the Fort George links was in the compound that included the former Junior Commissariat Officer’s Quarters, still standing today. During the summer militia camps the building was also used as headquarters.

The men’s trophy winner for the International Tournament in 1895 was American, Charles B. McDonald, whose grandfather had been a British Army surgeon at Fort George in 1812. In a strange twist of fate, two of his chief competitors, the Dickson twins, were grandsons of William Dickson who had been imprisoned by the Americans in the War of 1812. The female champion was Miss Madeleine Geale, described as “having the prettiest golf stroke among women players.”[21]

In 1895 McDonald had won the prize for longest drive at 179 yards. With improvements in golf club design and construction, and in particular introduction of the new rubber-cored golf ball,[22] longer drives were inevitable and the length of the fairways had to be increased several times.

Golf Club House, Niagara-on-the-Lake, postcard, circa 1902. The eighteenth green was in front of the golf clubhouse, shared with the Camp Niagara commandant in the compound.

Courtesy of the John Burtniak Collection.

In the languid years leading up to the Great War, the golf course at Niagara was a very pleasant place to spend a summer’s day.

… the black man with roller, shears and cart, the caddies lazily or eagerly searching for a lost ball, the scarlet coats, white shirt waists, the graceful swinging movement in a long drive, and the intent gaze forward as the ball rises, and falls true to aim to the destined spot.[23]

There was apparently room on the Mississauga Common for two courses, as in 1905 the Queen’s Royal Hotel formed a second golf club. All this came to an abrupt end on the eve of the Great War as both commons were eventually converted into military training camps. Soon the links were covered in canvas tents. The commandant’s headquarters occupied the compound full time.

The eighteen-hole Fort George links were never reopened although the club retained the lease on the property until the 1960s. Play resumed on the Mississauga Commons, initially operated by the Queen’s Royal Hotel. However, when the latter was closed the 1920s, a group of enthusiastic golfers formed the Niagara-on-the-Lake Golf Club. Originally the course used only the perimeter of the Mississauga common with one green within the ramparts of the fort. Reconfiguration of the course allowed for longer fairways; the green for the second hole was still within the ramparts and there were at least two tees built on the ramparts. During the Great Depression many a local lad worked as caddies for thirty five cents an eighteen-hole round, but if the ball were lost, the caddy was held responsible and there would be no pay![24]

In the 1960s the federal government decided to renovate Fort Mississauga and convert the Mississauga common into a National Historic Park. Initially it was proposed that the golf club could reactivate its lease on the Fort George common and construct a new eighteen-hole course there. After much correspondence it was eventually decided that the golf club and the fort could continue to co-exist on the Mississauga common, provided that the second hole be relocated outside the ramparts and the tees on the ramparts be eliminated. In 2002 a new walkway was created from the corner of Front and Simcoe Streets out to the fort’s entrance providing greater public access to the historic site.

Miss Madelaine Geale, photo, circa 1895. A local girl, Miss Geale, won the Women’s International Tournament held at Niagara in 1895.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #982.384.b-18.

Today the Niagara-on-the-Lake Golf Club continues as a privately owned club with a long-term lease from Parks Canada. The recently rebuilt clubhouse and pro shop sits on private property. There are few golf courses in North America with such a vista across an international river to Fort Niagara and along leafy fairways towards an original two-hundred-year-old Fort Mississauga. Many club trophies have been awarded since the 1800s.

Any discussion of golfing on the two commons would be remiss without reference to one of Niagara’s native sons, Lancelot Cressy Servos. As a young man he travelled to the United States, which was just starting to embrace the game of golf. A tournament champion and golf pro himself, he also wrote one of the first instruction manuals for golf.[25] He laid out and constructed some of the earliest golf courses in the southern states and also designed innovative golf equipment. For anyone who has ever picked up a golf club, the introduction to his book says it all:

Time marches on. Man conspires, respires, aspires, and expires. During which sojourn, if he is fortunate he plays a little golf and perspires. He may get so he plays it well, or he may not get to play it as well as he would like. It is for those who would like to improve their golf that this book is published. For what gaineth a man if he acquire the whole world and yet is unable to play golf.[26]

Lacrosse and Bandy

The Indian Council House in the middle of the Commons symbolized the covenant chain of friendship between His Majesty’s Indian Allies and the British government. Every year thousands of Natives from much of what is now southern Ontario, and to a lesser extent western New York, would come here for their annual presents, to air their grievances, and to negotiate treaties. With so many young Natives assembled in one place, the wide-open grassy plains of the Commons were a natural playing field for stick-and-ball games such as lacrosse and bandy. After a long day of council meetings, lacrosse and bandy were often played in the lingering summer daylight.

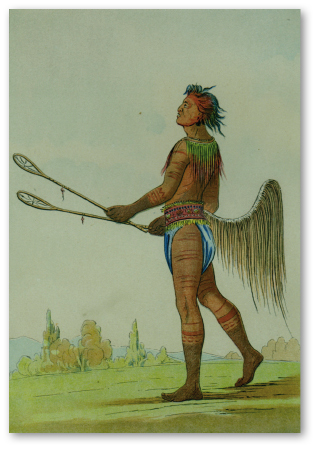

Drinks the Juice of the Stone, in ball-player’s dress (Choctaw, 1834), artist George Catlin, hand-coloured print. Various forms of stick-and-ball games were played among the indigenous peoples of North America. The Military Reserve/Commons with its Indian Council House was a popular venue.

Originally published in George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians (London: Tosswill and Myers, 1841), 223.

Stick-and-ball games were played among First Nations long before Europeans arrived in North America. Lacrosse may have originated among the Algonquins, but arguably the Iroquois became the masters. The Ojibwa called the game “baggataway,” but soon after contact the French called the game lacrosse because the playing stick resembled a bishop’s crosier.

In its early Native version, the playing field could be several miles long and hundreds of feet wide. The object of the game was to hit a single pole by the ball or to get the ball between two posts that could be tens of feet apart. The sticks, made of various types of wood, were strung with strands of spruce roots or deer hide. They were often decorated and were the owner’s prize possession. The “ball” could be simply a knot of wood or more commonly a ball made of hide stuffed with hair.[27]

The game was considered a gift of the gods and had a strong spiritual component. Natives might travel hundreds of miles to participate in the larger contests. The men would prepare themselves physically, emotionally, and spiritually, encouraged by their shaman who acted very much like a coach. At the start of the contest they would strip down to their breech-cloth, decorate themselves in war paint, and take to the field. It’s a small wonder the Cherokee called this sport, which stimulated such intense exhilaration, “the little brother of war.” The only two rules of the game were there had to be an equal number of players on both teams (which could be hundreds of players) and it was forbidden to touch the ball on the ground with your hand. Otherwise, the sky was the limit. The famous American artist George Catlin, who recorded the demise of the Native way of life in nineteenth-century America, described a typical match:

…hundreds are running together and leaping, actually over each other’s heads, and darting between their adversaries’ legs, tripping and throwing and foiling each other in every possible manner, and every voice raised to the highest key, in shrill yelps and barks.[28]

The games could go on for three days. There were often thousands of spectators to watch such contests. Besides the pride and sheer exhilaration of it all, the winners were often rewarded with strings of wampum, bracelets, necklaces, etc. Sometimes Natives and non-Natives would place wagers on the outcome.

It was a non-Native Montreal dentist George Beers who felt compelled to modify and codify the game of lacrosse, specifying the size of the field, rules of the game, equipment, and so on. At the time of Confederation, lacrosse was so popular that it was unofficially the national game of Canada.[29] Ivy League American colleges adopted the game and exhibition teams travelled to England where it became very popular, especially among women.[30] Sadly, many of the best players who were Native were unable to play in the big “amateur” tournaments because they couldn’t afford the travel costs yet couldn’t accept travel subsidies.

By the turn of the century baseball was becoming more popular than lacrosse during the summer months. With growing enthusiasm for ice hockey, arenas were being built. This resulted in the introduction of “box lacrosse,” which could be played in the empty hockey arenas during the summer. Today, field and box lacrosse are flourishing once again at both the amateur and professional levels.

It is not known how many spirited matches of lacrosse were played on the Commons by visiting Native tribes in the shadow of the Indian Council House. We do know that in 1804, poet Thomas Moore, the bard of Ireland, visited Niagara and was entertained by then Colonel Isaac Brock for ten days. Years later, he recorded that he accompanied Brock “on his going to distribute among [the Natives] the customary presents and prizes … the young men exhibited for our amusement in the race, the bat-game, [sic] and other sports.”[31] This may have transpired at the Fort George Indian Council House or farther afield.

The last recorded international lacrosse tournament on the Commons was held in 1860 between the old rivals, the Mohawk Nation of the Grand River and the Seneca Nation of western New York. There was “an immense” number of Natives in attendance and “thousands of spectators” watching the contest. After many hours the Senecas won the day.[32]

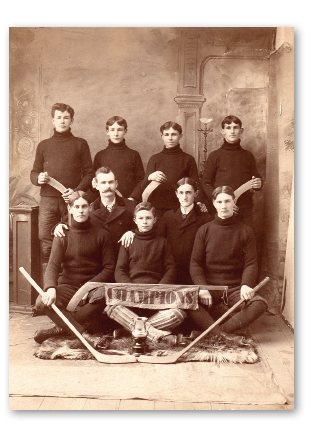

Champions, photo, circa 1900. Niagara produced several ice hockey championship teams who practised on the ice rink within the half-mile racetrack at Castlereagh and King Streets.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #989.5.407.3.

The game of bandy is also mentioned in early references to the Natives at Niagara. In the Memoirs of John Clark,[33] whose father was barrack master at Fort George until his death in 1808, he refers to the visit of HRH Prince Edward to Niagara in September 1792. According to Clark, “The most youthful Indians entertained His Royal Highness and suite with a game of bandy ball and foot races, on the common of Niagara.” Later Clark refers to this game of bandy where “there is a deal of animation and dexterity” as “resembling cricket.” There were likely many variations of the Natives’ stick and ball games: some perhaps similar to cricket, but others were probably more like field hockey or the more popular lacrosse.

Hockey

Informal games of “shinny” or “shinty,” described as hockey without skates, were played on frozen ponds on the Commons long before the advent of organized ice hockey.[34] During the first half of the twentieth century there was an ice rink within the racetrack of the agricultural grounds on Castlereagh Street. Niagara produced several very competitive hockey teams.

Foot Races, Walking, Hiking, and Jogging

Anyone familiar with the Commons today knows that walking or walking the dog are probably the most common recreational pursuits on the Commons today. Whether following the various established trails, many of which are now paved, or blazing your own path across the greens or through Paradise Grove, the vista is forever changing and the air fresh. Recalling the wonderful[35] Indian foot-races of days gone by, joggers may want to quicken their pace as they pass the Indian Council House site on the Commons.

Cycling

Since some of the trails of the Commons are now part of the Bruce Trail, the Waterfront Trail, the Greater Niagara Circle Route, and the Upper Canada Recreation Trail systems, cycling on the Commons can be a leisurely pastime or part of a real physical workout. Since its invention, the bicycle has been a popular mode of transport in town used by locals travelling about, often cutting through the Commons to get from point A to point B. Because of the large size of Camp Niagara, bicycles were often used by military couriers within the camp.

Early morning walk, Cosmo Condina, 2011.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Tennis

The first recorded tennis courts were situated on the King Street edge of the Commons near the grandstand. Later they were moved to their present site in Veterans Memorial Park, where they are maintained by an active tennis club.

The Otter Trail, photo Cosmo Condina, 2010. The historic Otter Trail in autumn. Note the modern soccer pitches on the left. The grassy field on the right was the site of the Indian Council Houses and later the military and civilian hospital.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Recreational Fishing and Hunting

We know that for thousands of years Native peoples have had campsites at the mouth of the Niagara River primarily because of abundant fish: whitefish, bass, and in particular sturgeon. Off-duty soldiers would often be seen at the Navy Hall wharf trying their luck. A very significant commercial fishery also thrived in Niagara for over one hundred years (see chapter 21). Surprisingly, there was a spring-fed fishpond on the Commons just below the northeast bastion of the fort. Built of stone, the pond was stocked with fish and was the exclusive preserve of the officers of the garrison.[36] Years later an archaeological dig confirmed its existence. The spring is still there, but the pond disappeared long ago.

In earlier times boys would often be seen on the Commons hunting birds and various small animals. One such expedition ended in tragedy when twelve-year-old Master Stocking, while in the company of several boys on the Commons, accidentally shot himself in both thighs.[37] Joseph Masters recalled that boys often trapped birds such as pigeons, sparrow, and snowbirds in nets strung out on the Commons. The captured birds would later be used for shooting matches. “Not much sport for the birds.”[38]

Soccer

An early version of this now very popular team sport was known as “Association Football”[39] and was played on the Commons. Two regulation fields with night lighting now grace the Commons. So as not to disturb the possibly rich archaeologically original sub-soil of the Commons, much topsoil was brought in to top up the fields.

Kite Flying

Wide open green spaces and a brisk wind will always make for an exhilarating day of flying one’s kite, especially if it’s homemade.