Chapter 21

On the Edge: Overlooking the Commons

Although the Military Reserve/Commons at Niagara in 1800 was considerably larger than most contemporary commons or greens, it still retained elements of the quintessential village green because its large, open green space was bordered by public and private buildings. This attribute was recognized by citizens and visitors alike. A walk around the edge of the official boundaries of the Military Reserve on the eve of the War of 1812 would mean strolling from the river’s edge at the foot of present King Street southwest to John Street, turning south, and then eastward along what is now John Street East to the banks of the Niagara River. With the exception of the stone powder magazine in Fort George, all the original buildings in the town were destroyed during or shortly after the War of 1812. Most streets in town were not assigned their present names until the 1820s.[1]

It is important to remember in the original survey, King Street was laid out with a generous ninety-nine-foot-wide street allowance (one and a half chains),[2] and was aligned due south-southwest. It appears that until the 1870s there was a guardhouse in the middle of the road allowance at the river’s edge and at times a “Ferry house.”

All the land bounded by King and Front Streets and the Niagara River was also designated a Military Reserve but from the earliest years most of the site[3] was occupied by the Royal Engineers’ Yard. This “complex,” rebuilt after the War of 1812, consisted of a number of buildings including the commanding officer’s quarters[4] with various outbuildings, offices, a carpenter’s shop, and quarters. As with the rest of the garrison at Niagara, activity here varied according to the perceived military threats of the day. With the final redeployment of British forces to other parts of the empire, the land with its fabulous view of the mouth of the Niagara River was acquired by the town in the late 1860s for the luxurious Queen’s Royal Hotel.[5] Tennis courts and a lawn bowling green were laid out at this end of the property and became the venue for important international tournaments well into the twentieth century. The area fell silent with the final dismantling of the hotel and its sports facilities in the 1930s. The town acquired the property in a tax arrears sale and set aside this usually quiet idyllic spot as Queen’s Royal Park, enlivened by annual Lions Club’s carnivals, a community skating rink, and the popular “Niagara Lions Beach” for public swimming. These facilities are now long forgotten by most or moved to other venues; the park still comes alive with an annual art show on Canada Day. The gazebo was built as a prop for a motion picture shoot in 1983[6] but has become a popular fixture of the waterfront. The site has also been the starting point for many famous cross-lake swimming marathons.

The Foot of King Street, artist Francis H. Granger, watercolour, circa 1856. Looking up from the river’s edge, the Guardhouse stands in the midst of the wide expanse of King Street. On the left is the Elliot House or Whale Inn built on land leased and later purchased from the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company. This Niagara icon still stands today at the water’s edge. On the right are the Gleaner printing office and adjoining Oates tavern. The green space beyond to Front Street is reserved for the Royal Engineers. Soon all the buildings on the right would be demolished to make way for the Queen’s Royal Hotel.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #988.189.

Lot 1 at the corner of King and Front was granted to merchant Francis Crooks. Facing the Commons, an early inn, The Yellow House, also known as the King’s Arms Hotel, was operated by Thomas Hind who welcomed many guests, including the celebrated transcontinental explorer Alexander Mackenzie.[7] After the war the present building was erected and for many years served as offices of the Bank of Upper Canada. Somewhat altered, including the addition of a veranda, the home is now the Old Bank House Bed and Breakfast.

On the adjacent lot stood the town’s original jail and temporary court house. Private residences now occupy the site.

At the northwest corner of King and Prideaux stood the Freemasons’ Hall, described as “a neat compact building of wood and plaster.”[8] When Lieutenant Governor Simcoe arrived in 1792 he opened the first session of the first parliament of Upper Canada in this multi-purpose hall with great pomp and ceremony. (The newly renovated Rangers’ Barracks on the Reserve would host the remaining sessions.) In addition to its prime function as a Masonic lodge, it served on occasion as a court house, ballroom, meeting place for the British Indian Department, and for divine services. In 1818 John Eaglesum erected the present substantial building of stone (later plastered and grooved to resemble blocks), apparently much of it gathered from the rubble of the burned town. It too served many functions in town including a store, a tavern, a private school, a public school, a grammar school, a dancing academy, and, during the Rebellion and Fenian alarms, as a barracks, hence its common name, “the Stone Barracks.” In 1877 it was purchased by Niagara Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M., and has served as their lodge ever since. Today the Masons meet in the upper rooms, where they maintain a significant archives of early artifacts. The downstairs is currently leased as a gallery. Before 1812, inkeeper John Emery owned a portion of this lot on which he built a substantial house and/or inn facing the Commons.

Niagara Masonic Lodge No. 2., postcard, circa 1920. Standing on the site of the original Freemasons’ Hall, the present building, known on occasion as the Stone Barracks, has served many functions. The Masons currently occupy the upstairs.

Published by F.H. Leslie, Ltd. Author’s collection.

Prior to the war, the intersection of King and Queen Streets was the most prestigious residential address in town, flanked by William Dickson’s Georgian brick mansion on the northeast corner and David William Smith’s equally impressive home on the opposite block. Both residences enjoyed views of the Commons.

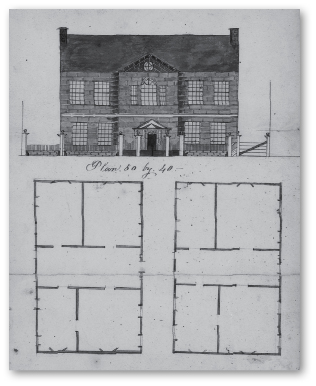

William Dickson’s house, 1815. In his extensive war loss claims, Dickson declared his town house was the first brick house in the province. The fine architectural embellishments of his home’s front façade were remarkable in eighteenth-century Upper Canada.

Library and Archives Canada, NMC C-126553.

William Dickson obtained the half-acre Lot 64 from Crown grantee David Secord.[9] There, as early as 1793, Dickson erected his impressive two-and-a-half-storey brick mansion facing King Street and the Commons. Interestingly, according to his war loss claims, Dickson and his family had taken up residence in his “new” home on his John Street property on the eve of the war. Dickson had acceded to Brock’s personal request that his King Street residence be used as a barracks. Ten months later, just before the American invasion, he had signed a formal lease of £75 Halifax currency per annum, but claimed that much damage had already been done by the occupying regular army, American prisoners, and militia. After the burning of the town only the brick walls were left standing.[10] Lot 64 was eventually severed; the eastern portion remained residential with the eventual erection of the substantial Queen Anne revival home, beautifully restored and maintained today as the Preservation Gallery. The building that occupies the Queen Street portion of the lot today, The Niagara Apothecary, is probably the most photographed building in town. Originally constructed in 1820 and initially occupied as a lawyer’s office, it was renovated to its present Italianate glory in 1866 and is the oldest continuing pharmacy in the province, if not the country. Preserved by the Niagara Foundation and restored by the Ontario College of Pharmacy, today it is a pharmacy museum now maintained by the Ontario Heritage Trust.

The Niagara Apothecary, photo Cosmo Condina, 2010. Light and shadows on Italianate glory.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

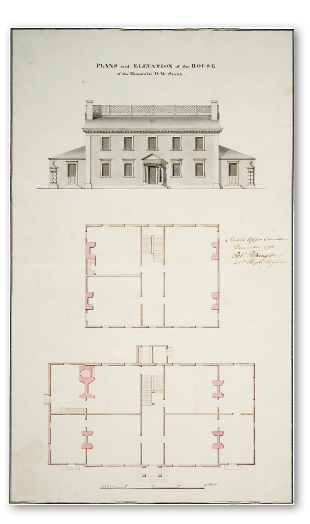

Plans and Elevations of the House of the Honourable D.W. Smith, artist Robert Pilkington R.E., drawings on paper, 1797. Georgian elegance overlooking the Commons.

Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room, D.W. Smith Papers, B 15-39.

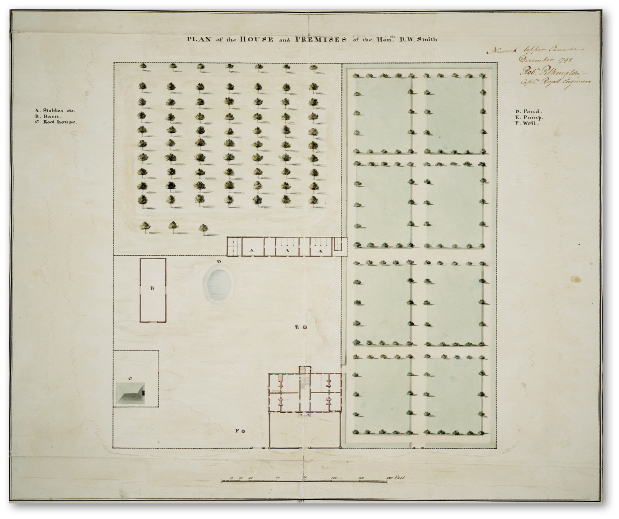

Plan of the House and Premises of the Hon.ble D.W. Smith, artist Robert Pilkington, drawing on paper, 1798. The house, outbuildings, formal gardens, and orchards occupied the entire Queen, Regent, Johnson, and King Streets block.

Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room, D.W. Smith Papers, B15-38.

Across Queen Street the entire block of four one-acre lots bounded by Queen, Regent, Johnson, and King Streets was granted to Acting Surveyor General of the Province David William Smith.[11] According to a plan of this property drawn up prior to his departure for England, we see a handsome symmetrical two-storey building with a widow’s walk above. Frame in construction, it was described as “constructed, embellished and painted in the best style.”[12] In 1803 the entire block was sold to the Crown with Smith’s home designated as Government House. It is here that the bodies of Isaac Brock and John Macdonell lay in state after the Battle of Queenston Heights. Eventually the block was transferred to the Town of Niagara. In an unsuccessful attempt to maintain the county seat in Niagara, the town fathers erected the handsome court house halfway along the Queen Street portion of the block, flanked by various mercantile premises. A large market square occupied the centre of the block.

Over the years a variety of businesses occupied the King Street side of the block. In the early twentieth century a ticket station for the electric car was built; it survives today as an upscale coffee emporium. Farther along towards Johnson Street stood Greene’s Livery, a somewhat ramshackle and odoriferous collection of stables and carriage barns but well patronized by locals and visitors alike. One local recalls racing down King Street to Greene’s after school. After helping to clean out stables and groom some of the horses she would be allowed to ride her favourite mount down Queen Street.[13] At an hourly rental rate of $1.50 local kids could ride one of Greene’s horses out onto the Commons on trails as far as Paradise Grove. However, every time the horse came to a cross-trail he would invariably try to turn back towards the stables.[14] Architectural elements of the old Livery are now incorporated into a fancy restaurant. Next door, the Town’s tall stone-and-brick water tower stood sentinel for many years.

The next block between Johnson and Gage Streets was in part granted to William Crooks, one of the four Crooks brothers, all enterprising Scottish merchants. William and his brother James were the first merchants to ship wheat to Montreal and were co-owners of the schooner Lord Nelson, which was confiscated by the Americans and renamed the Scourge on the eve of the War. William married a granddaughter of Colonel John Butler and served with distinction as a captain of the militia at the battles of Queenston Heights and Lundy’s Lane. He later moved to Grimsby. The other half of the block was granted to the canny Queenston merchant Robert Hamilton, who probably regarded this choice lot as a good investment. Today private residences occupy the block.

The next block of town lots was granted to members of the McDonell family. Allan McDonell of Collachie had emigrated from Scotland to the Mohawk Valley, New York, in 1773 and served in the Royal Highland Emigrants Regiment during the American Revolutionary War. His wife Helena and their two daughters were taken hostage, but eventually the family was reunited in Quebec. After Allan’s death Helena and her three sons were awarded the four town lots in Niagara as partial compensation for their military service and war losses. Angus received the one-acre lot at King and Gage Streets. He dabbled in various enterprises such as potash and salt springs, but he was also a founding member of the Law Society of Upper Canada. In late 1792 he was delegated by Simcoe as first clerk of the House of Assembly which met nearby. Later in 1804, while travelling to Newcastle to defend a Native charged with murder, he perished when the schooner Speedy sank in Lake Ontario during a sudden storm.

The youngest McDonell son, James purchased a commission in the 43rd Regiment but died while stationed in the West Indies.

The third brother Alexander McDonell (1762–1842) served as a lieutenant in Butler’s Rangers. In 1792 he was appointed sheriff of the Home District that included Niagara. As Colonel in the militia he was captured at the Battle of Fort George and imprisoned. He also served as a land agent for Lord Selkirk and later as member of the House of Assembly for twenty years. The widowed mother Helena received the lot at King and Centre Streets. She died in 1797 and was probably buried in St. Mark’s Cemetery.

The three acres (excluding Alexander’s lot) were purchased by Judge Edward Campbell in 1846 and he built a substantial brick house facing the Commons. By 1864 the property was being leased by “J.B. Plumb, Alien,” but in 1871 Josiah B. Plumb purchased the property from Widow Campbell for $3,000. Plumb, an American, had come to Niagara to see “the most beautiful Street in the world,” namely his future wife Elizabeth Street.

Alexander McDonell (1762–1842), artist William Berczy, watercolour, gouache over graphite on woven paper, 1803. McDonell’s varied career included army and militia officer, office holder, politician, and land agent. The McDonell family was granted the entire block now occupied by Parliament Oak School.

Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM, 970.85.1.

Many additions and improvements were made to the house and gardens including a third floor billiards room reached by a secret staircase installed just before the private visit of HRH Prince George the future King George V. Plumb eventually became the Speaker of the Canadian Senate just before his death in 1888. In 1917–1919 the mansion was occupied by officers of the Polish army training in Camp Niagara. In 1920 the property was acquired by the White family. A daughter, Anne White Buyers,[15] recalled growing up in the house that boasted ten fireplaces, four staircases, and elaborately carved woodwork. In 1943 the house was torn down to make way for a new public school. Many architectural elements were saved and some were installed in local residences. The school, which still occupies the entire block, was called Parliament Oak School, hence the carved stone bas relief on its south wall facing the Commons. The school’s name was based on a legend that during a spell of hot weather one of the sessions of the first parliament had been held under a huge oak tree on the property. Such a meeting has never actually been documented. Perhaps one could imagine the Clerk of the House of Assembly, Angus McDonell, suggested that rather than enduring yet another meeting inside the hot and stuffy Rangers’ barracks, the members reconvene under a shady oak tree on the edge of his town lot.

Senator Plumb’s house, photo, circa 1920. Viewed from across a corner of the Commons at Castlereagh and King Streets, Senator Plumb’s mansion dominated the block now occupied by Parliament Oak School. Note the railway crossing sign at King and Gate Streets.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2011.025.007.

The corner lot at King and Centre Streets was granted to James Clark who had “fought with Wolfe” at Quebec. The old soldier later served as barracks master at Fort Niagara and later at the new Fort George. In the 1830s, lawyer and registrar of the county Mr. Lyons married a Mrs. Geale, a member of the Claus family that lived next-door. They built the handsome house still guarding the corner. Interestingly, the house with its splendid doorway and curious blind windows faces the side street but a large bank of windows overlooks the Commons.

The next two adjacent King Street lots, including the William Street road allowance and the two lots immediately behind, have been one parcel of land since the early 1800s. Long referred to as “Geale’s Grove,” this remarkable property in the midst of town has been known as “The Wilderness” for at least the past century. According to legend, the Six Nations Indians presented this four-acre property to Ann Claus, widow of Daniel Claus and daughter of the much-revered Superintendant of Indian Affairs Sir William Johnson. Ironically, the Natives had to buy the tract of land from one of the original white grantees, Lieutenant Robert Pilkington of the Royal Engineers. Ann died in 1801 and the property was inherited by her son William, who was appointed deputy superintendant of Indian Affairs. We do know Natives frequently visited Claus on official business, but they would often appear unannounced in the spring to collect buds from the huge Balm of Gilead trees from which they would make a salve for eye disorders.[16] In the middle of this Carolinian forest with over twenty-five varieties of trees and shrubs, including huge oak[17] and buttonwood trees, the first house was built near the edge of the One Mile Creek, which meanders through the property. After the burning of the town the family members apparently survived the winter in a root cellar which endured into modern times. After the war, Claus began construction of the present house farther up from the creek. The new home was a one-storey rambling bungalow with many subsequent additions which sits today contentedly under a huge canopy of trees out of view from the street. Claus and his wife Catherine kept meticulous notes of their horticultural endeavours, which provide a unique window on pioneer gardening practices of the day.[18] With only a short hiatus the current owners have enjoyed the property for over ninety years.

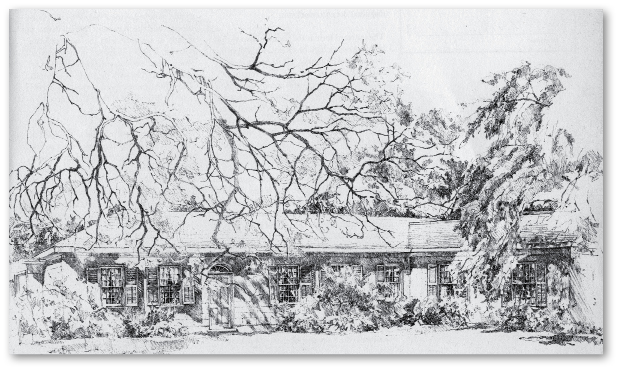

The Wilderness, artist Robert Montgomery, drawing on paper, 1970. The artist captured the quiet beauty and contentment of this regency villa, known today as The Wilderness, surrounded by over four acres of Carolinian woods in the midst of town.

Published in Peter John Stokes, Old Niagara on the Lake (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), no. 57. Courtesy of the artist, Robert Montgomery, the author Peter Stokes, and the publisher, © University of Toronto Press.

The corner lot at King and Mary Streets was apparently acquired by John Powell Senior from the grantee Benjamin VanEvery prior to the War of 1812. Powell, a son of Chief Justice William Dummer Powell, held local government positions and served with distinction in the Lincoln Artillery during the Battle of Fort George. His wife Isabella was a daughter of Adjutant General of Upper Canada and former Queen’s Ranger officer, Major General Aeneas Shaw. Another Shaw daughter, Sophia, was said to have been a love interest of Isaac Brock. As early as 1818 Powell began construction of his new home of brick but finished in stucco, grooved to resemble cut stone blocks so fashionable in the Regency period. Again, large front windows faced onto the Commons. After Powell’s death in 1826 the family continued in the home for another ten years when lawyer and businessman James Boulton acquired the property. There have been a number of changes over the years but the home, now known as Brockamour because of the possible Brock connection, is operated as a popular bed and breakfast.

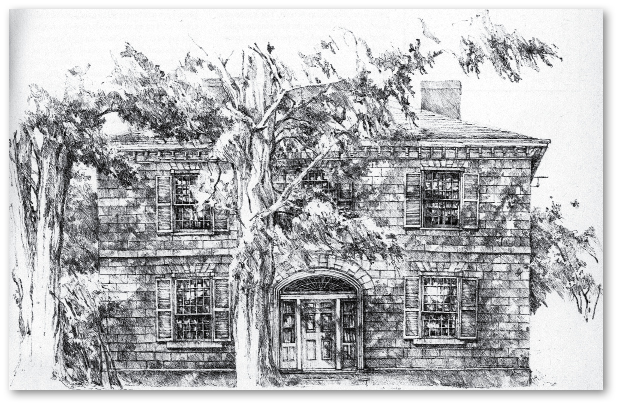

The Powell-Cavers House (Brockamour), artist Robert Montgomery, drawing on paper, 1970. The solid symmetrical façade of this handsome regency house surely reflects the builder’s appointed position as registrar of the county. Generous windows provide wide vistas of the Commons.

Published in Peter John Stokes, Old Niagara on the Lake (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), no. 56. Courtesy of the artist, Robert Montgomery, the author Peter Stokes, and the publisher, © University of Toronto Press.

The last two lots on King Street facing the Commons are occupied by a private late-Victorian brick home and sometime gallery, and by the Pillar and Post Hotel. The two original Crown grantees were loyalist John VanEvery and William Duff Miller, stationer and local government official. The latter must have flipped his grant, as he built his new home after the war at the corner of Mary and Regent Streets and it still stands, recently restored by the hotel. The main portion of the Pillar and Post facing John Street was originally a canning factory that hired at its zenith hundreds of seasonal workers. A railway spur was extended northward along John Street West to provide service to Camp Chautauqua.

The road allowance for what is now John Street East was originally known as “The Carriage Trail” or “The Carriage Road Trail” and was well within the Military Reserve by up to fifty feet. This created jurisdictional conflict between the town and the federal government as to who was responsible for road maintenance, snow removal, and so forth. Moreover, the property owners along John Street had to cross over federal property for access to the road. It was not until the 1960s that these legal difficulties were finally settled whereby the Crown produced quit-claims to the lands for nominal financial consideration from the relieved property owners.[19]

Vine-covered wall, photo Cosmo Condina, 2011. The privately built substantial brick, stone, and cement wall along John Street East was probably encroaching on the edge of the Military Reserve.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

The twenty-plus-acre lot on John Street between King and Charlotte Streets was granted to Lieutenant Robert Pilkington. Besides being a good artist he was also a favourite of Mrs. Simcoe, which may account for his being the happy recipient of some choice pieces of land. However, much of this lot, which was known locally as the “23 acre fields,” was in the flood plain of the One Mile Creek. In the 1860s William Dickson’s third son, the Honourable Walter H. Dickson,[20] owned this lot and he may have erected several small cottages for his help, and possibly a small racecourse on the property.[21] There has been one happy survivor from this period — the “Dickson-Potter House.” This is a delightful mid-Victorian board-and-batten cottage nestled amongst drooping trees. It is approached by a small bridge over the One Mile Creek. Local historian Kaye Toye has enjoyed looking out onto the Commons for ninety years. The old railway right-of-way that cut diagonally across this lot is now preserved as the Upper Canada Recreation Trail. The rest of the property has undergone residential development.

Beyond Charlotte Street[22] the high and somewhat foreboding brick and stone walls give a taste of what lies behind — which can only be glimpsed through closed wrought-iron gates. Peter Russell, the administrator of the province after Simcoe left for England, was granted 160 acres that included the John Street frontage all the way to the end of the present picket fencing. With the move of the capital to York in 1797, Russell was forced to sell his lands, including his leased property, “Springfield” in the middle of the Commons, and this tract of apparently unimproved land. He sold the land to William Dickson, who had already built his brick mansion at King and Queen Streets.

The Dickson-Potter house, photo Cosmo Condina, 2010. The current owner has enjoyed the ever-changing views of the Commons from her front veranda for ninety years.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

Dickson had arrived in Niagara at age sixteen and may have initially worked for his cousin, the merchant Robert Hamilton. Eventually the canny Scot became a lawyer, judge, land developer, and member of the Legislative Council. Along the way he was involved in a duel in which his antagonist, fellow lawyer and member of the assembly William Weekes, was fatally shot.[23] In Dickson’s war loss claims he enclosed a drawing of a brick bungalow which was completed a year before the outbreak of war and was probably situated on his John Street farm property. After the war he may have built a two-storey house on the western end of his John Street property that was eventually called Rowanwood. Although he continued his law practice most of his energies were directed to his large land holdings on the Grand River. Finally in 1827 after his wife’s death, he actually moved there to directly oversee the development of Dumfries Township and its prosperous village of Galt. The Honourable William Dickson (Dickson was appointed a member of the Legislative Council and given the title of “Honourable” for life) returned to Niagara in 1836 probably taking up residence again at Rowanwood to devote the remnant of his life to “high and solemn purpose.”[24]

Meanwhile, Dickson had divided up amongst his sons the rest of the huge estate. The “homestead” was given to his eldest son Robert, who proceeded to build his two-storey brick home and the extensive stables behind over the foundations of the original brick bungalow. He called his estate Woodlawn. Like his father, Robert was a lawyer and was very involved in community activities. He was also captain of the local cavalry troop of militia and frequently drilled his troopers on the Commons opposite his home. He and his wife had no surviving children so his estate was left to one of his numerous nephews. Eventually his youngest brother, the Honourable Walter H., who had inherited Rowanwood from his father, also acquired Woodlawn.

The Honourable William Dickson, artist Hoppner Meyer, watercolour, 1842. Merchant, lawyer, land developer, office holder, duellist, yet non-combatant during the War of 1812, Dickson owned 160 acres along the southern edge of the Commons.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #988.199.

In the 1870s the Dickson properties were sold to Americans who were part of that group of wealthy bankers and industrialists who sought relief for their families from the heat of Buffalo and Cleveland in leafy Niagara-on-the-Lake. A Civil War veteran and executive with the Buffalo and Erie Railroad, Brigadier General Henry Livingston Lansing purchased Woodlawn in 1873 and is thought to have been responsible for the third floor addition and tower. Next door, J.H. Lewis bought Rowanwood as a summer home and may have renovated the original frame building, as it is later described as a stone residence. George Rand Senior, a self-made man who eventually became chairman of Buffalo’s largest bank, purchased the Woodlawn estate in 1910 which he promptly renamed Randwood and proceeded with many additions to the house, as well as extensive landscaping. Nine years later he added Rowanwood to the estate and erected barns and gatehouses along Charlotte Street. After his father’s untimely death in a plane crash, George Rand II continued stewardship of the estate; Rowanwood was torn down in 1920[25] to make way for a park, but instead the present Devonian House was erected on the site for the newlywed Evelyn Rand Sheets. Mrs. Sheets, an accomplished equestrian, was often seen riding her horse along John Street and on the Commons.

The Dickson-Rand House (Randwood), artist Robert Montgomery, drawing on paper, 1970. On the foundations of William Dickson’s prewar country house, son Robert erected a substantial two-storey brick home. Later, summering American families added a third floor, a belvedere, and other embellishments.

Published in Peter John Stokes, Old Niagara on the Lake (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), no. 54. Courtesy of the artist, Robert Montgomery, the author Peter Stokes, and the publisher, © University of Toronto Press.

More outbuildings were added along Charlotte and further extensive landscaping of the grounds was carried out, including the first in-ground swimming pool in town. A gazebo-like station was built on the edge of the estate for the family’s private stop on the Michigan Central Railway line. George also had built the high wall around much of the estate. Eventually the property was inherited by George II’s son Calvin. Most of the estate was eventually leased to the Niagara Institute but then sold to the Devonian Foundation, which in turn sold the property to the School of Philosophy. Now in private hands, there are currently plans for development of this remarkable property.

The Honorable William Dickson gave his second son and namesake, William Jr., the ten acres on John Street to the east of present Randwood. Rather than develop his Niagara properties, William Jr. decided to move to Dumfries to develop the family’s holdings there, and so in 1829 he sold his lands for £200 to Robert Melville, a retired Captain of the 68th Regiment, which had been stationed at Fort George. This “public spirited, good-natured gentleman”[26] built the nucleus of the present two-storey brick house of three bay design with a very elaborate front doorway. He called his property Brunswick Place, apparently because he had met his wife in New Brunswick. Soon Melville was elected manager of the newly formed Niagara Harbour and Dock Company and a street in the new dock area was named after him. But his good fortune was not to last: he had to step down from the financially troubled Dock Company and each of his three young sons died before reaching their teens. The banks foreclosed on the property in the year of Confederation.

In the 1880s the Honourable William’s grandson, Robert George Dickson, purchased the property, made extensive embellishments and additions to the house, and renamed the estate Pinehurst, acknowledging a large grove of pine trees on the property. Robert and his twin brother, J. Geale Dickson, were avid golfers and were largely responsible for laying out the Fort George links on the Commons opposite Pinehurst. In 1895 the property slipped out of the Dickson family once again. A succession of American families owned the property, renamed Brunswick Place. The longest owners were the Letchworths, famous for their sumptuous parties still remembered fifty years later. The lady of the house, a petite, five-foot-tall woman, was a regular sight on the Commons riding sidesaddle on her horse Blue Shadows with her red setter Matey running alongside.[27] Artist Trisha Romance and her family are the current proud owners of the restored property. Architectural elements of Brunswick Place have been incorporated into several of her paintings.

The rest of the land between Dickson’s purchase and the river was granted to William McClellan. During the American Revolutionary War he was captured by Natives and rings were inserted in his nose and ears before his escape to Canada. According to his petition for land he settled on this gore-shaped tract of land adjacent to the Queen’s Bush in 1783. His son Martin had also been captured by another group of Natives but was liberated at Cherry Valley. During the War of 1812, Captain Martin McClellan of the First Lincoln Militia told his wife on the eve of the Battle of Fort George that he would not survive the fighting the next day. He gave her his pocket watch and purse for safe keeping. The next day he was mortally wounded by a musket ball that passed through his empty vest pocket where his watch was usually kept.[28] He was buried in St. Mark’s cemetery and his gravestone has now been affixed to an interior wall. After the war the land was eventually sub-divided and passed through several families including the Chittenden, Warren, McIntyre, Watt, Longhurst, and Nelles families. Today the property is occupied by private residences, Peller Estates Winery and Riverbend Inn. The immense white oak sentinel on the southern edge of the John Street road allowance near the intersection with the Niagara Parkway, and several trees in the Reserve to the southeast of the intersection towards the river are first growth. These trees have been silent witnesses as LaSalle, Simcoe, Brant, Brock, and various Royals passed by.

Brunswick Place, photo Cosmo Condina, 2011. Cosmo’s photo of Brunswick Place on a misty morning belies the rich architectural detail of this stately home that has gazed out over the Commons for over 180 years.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.

The final boundary of the Military Reserve was the Niagara River. Starting northward from John Street East the area including the present parking lot was occupied at one time by several cottages. To the north of this was a popular picnic area that extended into Paradise Grove which, for a while, was kept clear of brush and fallen branches. There was a stairway down the steep cliff to a mooring for small boats which brought picnickers from the town.[29] Farther along, two deep gullies along the western edge of the Niagara Parkway are remnants of the old railway line. Just beyond this was the Half-Moon Battery built during the War of 1812 period to counteract the opposing American River batteries. This was a two-storey semi-circular rampart built into the high riverbank. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by the Niagara Parks Commission when it extended the Niagara Parkway to the restored Navy Hall.

All the land along the Niagara River below the moderately high riverbanks from Navy Hall to the end of King Street was up to forty acres of low marshland. During some severe winters the banks were covered by heaped up river ice which could crush and sweep away substantial wharves and buildings. Moreover, the land was often flooded in the spring, leaving rotting stagnant cesspools during the warm summer months. Aside from a few plots set aside for merchants near the site of present Melville Street, this part of the shoreline was occupied by one or two ferry huts, an inn, and the guard house at the end of King Street. This was the edge of the Military Reserve/Commons on the eve of the War of 1812.

SS Chief Justice Robinson, artist Francis Granger, watercolour, circa 1855. Built by the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company during Niagara’s heyday as the busiest ship-building centre in Upper Canada, this steamer proudly plied the waters of Lake Ontario under Captain Duncan Milloy.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #2006.016.008.

In 1831, the NHDC, consisting of a group of local influential citizens, was granted ownership of all the marshland by the Crown.[30] Within the year they began the process of draining and excavating a deep basin, reclaiming approximately forty acres.[31] Ramps for launching ships and a marine railway were installed. Shipbuilding was the prime purpose of the company and the first boat, the schooner Princess Victoria, was launched in 1833, the same year that it opened its dry dock. Business was booming. Niagara was now the largest shipbuilding facility in Upper Canada, with a great surge in employment; in seven years the population of Niagara more than doubled. At least twenty-seven ships were built between 1832 and 1864.[32] Other industries were attracted to the dock area, including a tannery and a brewery thanks to abundant spring water nearby on the Commons. Nevertheless, the company was deeply in debt to the Bank of Upper Canada which itself was greatly overextended.

In 1853 local entrepreneur Samuel Zimmerman bought out the bankrupt company. With financial backing from the town, Zimmerman brought the Erie and Ontario Railroad to town with direct access to the docks, thus coordinating railway and steamship schedules. He began the manufacture of much needed railway cars in the same foundry already producing steamships. His untimely death four years later was a severe blow to the company’s ambitious plans, and within ten years no steamships were being produced, and the once-booming facilities were in disrepair. However, a brisk steamship business continued well into the twentieth century and the railway was also well patronized, but the boom years were over.

Other well-known boat building companies[33] prospered along the waterfront for a while, but they too have folded. There were also several family-operated commercial fishing businesses that operated out of this reclaimed area, now long gone. Canning and basket factories and the Niagara Oak Tannery also provided employment in the dock area for a time.

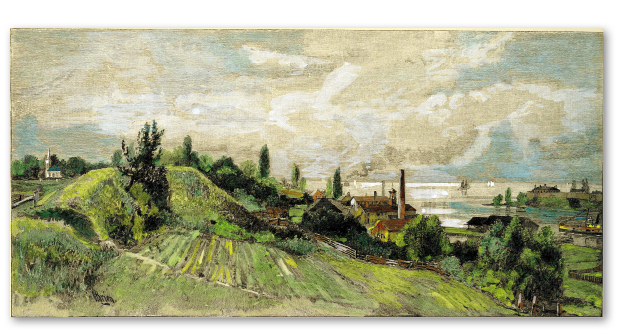

Mouth of the River from Ramparts of Old Fort George, artist L.R.O’Brien, wood engraving, circa 1880. This fine engraving reveals the industrial development of the waterfront, originally the marshlands of the Military Reserve. Note in the foreground the cultivation of a portion of the ramparts of the old abandoned fort reclaimed as common lands.

Originally published in George Monro Grant, ed., Picturesque Canada, vol. 1 (Toronto: Balden Bros., 1882), 374.

It is not the purview of this book to document all the residential and commercial buildings in this reclaimed area that roughly includes all that between Ricardo Street and the Niagara River. However, a few buildings are of note. The active Niagara-on-the-Lake Sailing Club still uses NHDC’s original 1834 storehouse on the dock. The NHDC’s manager’s office, tucked into the riverbank overlooking the harbour, has been carefully restored as a guest house. Other frame buildings built by the NHDC survive as private residences. A later brick building that served as the town’s water pumping station has been turned into a vibrant artists’ gallery.[34] The early twentieth century Foghorn Station on River Beach Road has been renovated by the Niagara Foundation as a guest cottage. Two early lighthouses still stand as silent reminders of a bygone era. The iconic, beautifully restored Whale Inn at the foot of King Street once welcomed sailors and travellers. Built in the 1830s by the Elliot family on reclaimed NHDC land it is now a private residence. So ends the tour around the edge of the original Military Reserve/Commons.