Chapter 23

The Mississauga Commons

A climb to the roof of Fort Mississauga’s tower reveals a spectacular 360-degree vista. To the east is the mouth of the majestic Niagara River and Fort Niagara beyond; to the south, over a canopy of mature trees, the old town of Niagara and the flagstaff of Fort George beyond; to the west the oldest golf course in Canada on the leafy Mississauga Commons; and to the north, a shimmering Lake Ontario with the twenty-first-century skyline of Toronto in the distance.

There is no archaeological evidence that Native peoples established any permanent villages at this juncture of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario known today as Mississauga Point.[1] By Native tradition it was a popular campsite because of the abundant fish nearby. After the disappearance of the indigenous Neutral Indians in the 1650s, the Iroquoian Seneca nation withdrew to the eastern side of the Niagara River and allowed the Mississaugas of the Chippewa nation to hunt and fish on the west side of the river. The French cultivated a “King’s Garden” on the fertile mud flats of the west side of the river to supply fresh foodstuffs for their garrison across the river in Fort Niagara. However, it was not until the British established a battery on the west side of the river (at approximately Queen’s Royal Park today) during the siege of Fort Niagara in 1759 that Europeans first established a military presence there. In May 1781, the Mississaugas signed a treaty whereby a strip of land extending four miles westward from the Niagara River, stretching from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie, was ceded to the British. It certainly seems appropriate that this site should commemorate the Mississauga Nation.

Given its commanding view of the mouth of the Niagara River and being situated directly across from the well-established Fort Niagara, it is not surprising that at least one British government official recognized its strategic importance as early as 1790.[2] Nevertheless, the heights above Navy Hall were chosen for the site of the future Fort George. In 1796 Lieutenant Robert Pilkington of the Royal Engineers established a military reserve at Mississauga Point,[3] although the land set aside was only approximately one half of the 52.4 acres (21.2 hectares) of the Mississauga Commons today.

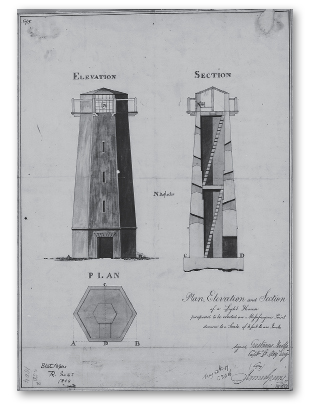

The government did recognize the maritime importance of the site. In 1804 the stonemasons of the 49th Foot built the first lighthouse on the shores of the Great Lakes.[4] The one and only lighthouse keeper was Dominick Henry, a retired officer of the Royal Artillery who lived with his wife and daughters in a log cottage nearby. Remarkably, the lighthouse, which was situated in what is now the inner edge of one of the fort’s lakeside glacis (battery), survived the war[5] but was dismantled by the British in 1814 with the stone incorporated into the tower.

Plan, Elevation and Section of a Light House Proposed to be erected on Mississaugua Point, artist Gustavus Nicolls, drawings on paper, 1804. This is the plan of the first lighthouse built on the shores of the Great Lakes. The artificers were the masons of the 49th Regiment of Foot.

Library and Archives Canada, NMC 0006243.

In February 1813, when it was apparent that Fort George’s location was not ideal, Lieutenant Colonel R.H. Bruyeres of the Royal Engineers recommended that “a tower or small Redoubt to command the entrance of the River is essentially necessary to be erected on Mississauga Point.”[6] However, it would not be until after the American invasion and recapture of the site by the British that Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond, administrator of Upper Canada, ordered the fortification of Mississauga Point. The fort would be “a temporary field work” in which the irregular star-shaped earthworks[7] with picketed ramparts would enclose several log barracks and a central masonry tower. Inclement weather delayed the actual start of construction past March 1814, but in a remarkable burst of war-time activity, by late July when the American army approached from the west, it was confronted by a formidable, albeit temporary, new British fortress. The fortified earthworks were nearly complete and four cannons were in place. The barracks were occupied, two bomb proof powder magazines in the ramparts were complete, as was a wooden sally port on the north side. There were also two functioning hot shot furnaces. However, the tower, being built partly from brick rubble recycled from the burned town, was still only two feet high. A few shots were exchanged and the Americans withdrew.

After the war there was much indecision as to the military importance of the Niagara installations. With Fort George in ruins emphasis was placed on consolidating the new Butler’s Barracks complex at the western end of the Military Reserve and initially to upgrading Fort Mississauga. A plan which was approved by Administrator Drummond called for the construction of a huge permanent fortress on the point, ten times the size of the present fort (in fact the present fort would have fitted inside just one of the huge bastions of the proposed mammoth fort) — all at a cost of at least £90,000.[8] At one point a ploughed trace of the proposed work was outlined on the site, but that is as far as the grand scheme progressed. However, in anticipation of a future need for a larger military facility the authorities undertook to enlarge the Military Reserve. A large tract of land surrounding the Reserve that was owned by the Honourable James Crooks was swapped for a large piece of the Fort George Commons.

View of Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario from the Light House on the British Side, artist unknown, engraved aquatint, Port Folio Magazine, 1812, 327. Naïve view of the lighthouse on Mississauga Point which was built of stone but the keeper’s cottage apparently was of timber construction.

Courtesy of Lord Durham Rare Books Inc.

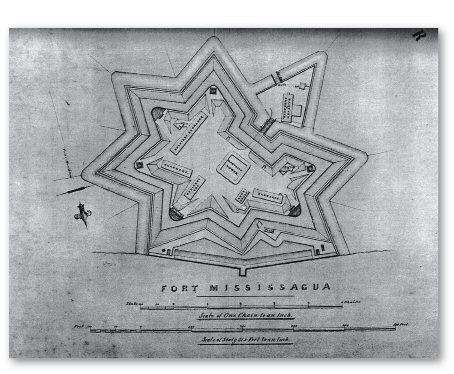

Plan of Fort to Be Erected at Mississaugue Pt., drawing on paper, April 8, 1816. This was the grandiose plan for a huge fortress on the point (upper right-hand corner), ten times the size of the present fort. The bastions would have extended as far as Simcoe and Front Streets. Although approved by the administrator of the province, Lieutenant General Drummond, the grand scheme was quietly abandoned by a cash-starved British government after the Napoleonic Wars.

Library and Archives Canada, NMC 17882.

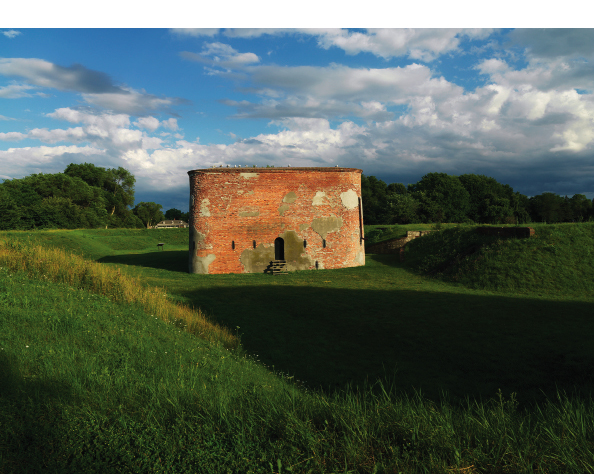

Meanwhile, construction of the tower proceeded slowly, not reaching completion until 1823. The finished tower measured fifty by fifty feet and was twenty-five feet high. The walls of brick and stone were eight feet thick at the base, sloping to seven feet at the parapet. In the basement were two rooms, one for storage and the other a powder magazine. The main floor consisted of two vaulted barracks rooms. In 1838 a temporary roof was finally replaced by a timber platform on the roof to support four moveable cannons. The exterior walls were originally supposed to be covered in stone, but instead were covered with a plaster or stucco parging, which has been a recurring maintenance problem ever since.

Fort Charlotte near Halifax was the only other fortification of this design — a square tower within a star-shaped earthwork — to have been built in Canada. Only Fort Mississauga has survived.

In response to the Mackenzie rebellion of 1837 some changes were made to Fort Mississauga, including adding a ravelin at the front entrance to enclose the officers’ quarters, a wooden sally port reconstructed in brick, and a dry ditch around the perimeter of the fort, which necessitated construction of both a trestle bridge and drawbridge. At least one contemporary visitor to the fort was not impressed. Author Anna Jameson remarked, “The fortress itself I mistook for a dilapidated brewery. This is charming — it looks like peace and security at all events.”[9]

Verification Plan, drawings on paper, 1852. This insert, Fort Mississagua, illustrates the central brick and stone tower plus several log buildings within the earthworks as well as a new ravelin to include the officers’ barracks at the front entrance to the fort.

Library and Archives Canada, NMC 11403.

Given the limited barracks space and the waning importance of Niagara in the overall military strategy in the decades after the 1822 transfer of British Army headquarters to York, Fort Mississauga was garrisoned on a limited and sporadic basis. Since the fort was heavily fortified with extensive ordnance there was always a contingent of Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers. Detachments of the various regiments that were stationed at Butler’s Barracks were on occasion assigned to Fort Mississauga. Local militia served at the fort as well. As one volunteer militia man in January 1865 recalled:

… these barracks proved very cold at night, winds from the north and east swept over the bastion heavy with spray, and so raw and penetrating as to make us shudder under our blankets and overcoats.[10]

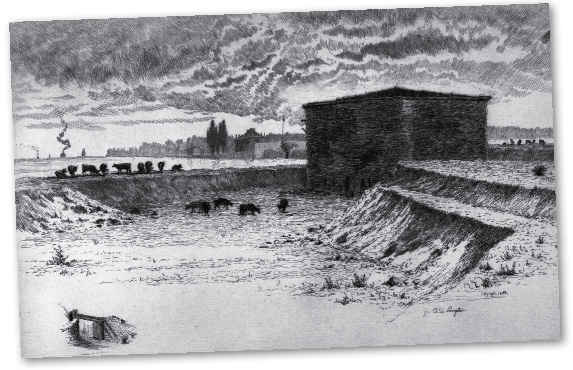

Moreover, the lake was taking its toll on the ramparts, with severe erosion being an ongoing concern. By 1858 when jurisdiction for the fort was transferred to the provincial government, the fort had been officially dismantled and the earthworks and buildings allowed to deteriorate. The garrison had been withdrawn. When historian Benson Lossing visited the site in 1860 he stated that the only “garrison” was a squatter, Patrick Burns and his family.[11] As with the other military sites along the border, when the American Civil War broke out, emergency repairs were made to the buildings as volunteer militia companies were rushed back in. Similar temporary excitement occurred in response to the Fenian Raids. In 1870 Fort Mississauga officially ceased to be a military work.

Fort Mississauga, artist A.W. Sangster, pen and ink sketches, No. XLVIII, 1888. Cows, cows, everywhere cows. With all the interior log buildings and artillery removed the abandoned fort was taken over by the cows, both here and on the Fort George Commons as well.

Courtesy of the author.

During the early Camp Niagara days the summer militia camps included occasional encampment on the Mississauga Reserve/Commons. However in 1874 the caretaker for the Military Reserve advertised for tenders to remove in whole or in part the tower and log buildings of Fort Mississauga.[12] Thanks to protests from the mayor and historians the government backed down and the fort was saved. There was renewed interest in the site by the locals. The local militia held their annual musters at the fort. The Mississauga Commons, which included all the land bounded by Simcoe and Queen Streets and the river (the Charles Richardson House remained in private hands), became a chosen spot for picnics and various public events. However, it was never as popular as the Fort George Commons. In 1878, the first golf links were established on a portion of the Mississauga Commons. A private golf club was formed shortly thereafter, which paid an annual rent to the government. Meanwhile in the 1890s the log buildings within the fort were quietly sold and dismantled by the owner of the Queen’s Royal Hotel to use in a breakwater for the hotel’s riverfront.[13]

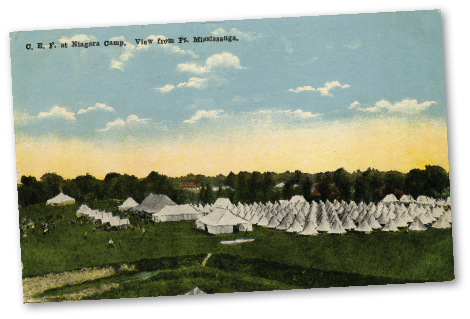

With the exception of the Camp Niagara encampment on the commons during the Great War, the Mississauga Commons (also known as the Lake Commons) has continued as a private golf course ever since. For years, the course’s second green was within the fort and two tees were played from the bastions. One golfer sued the government (unsuccessfully), claiming that he was hit by a piece of falling brick from the tower.[14] The presence of this unique golf course[15] has certainly limited the public’s daytime access to the Mississauga Commons and fort. Nevertheless, for generations locals have sneaked out to the fort along the river or lake paths for picnics, all-night parties, to carve their initials in the brick sally port, and as a lovers’ rendezvous. (One citizen quipped that half of Niagara-on-the-Lake was conceived out there!)

C.E.F. at Camp Niagara. View from Fort Mississauga, postcard, circa 1916. This was the view of the military encampment on the golf course/Mississauga Common from the roof of the tower.

Courtesy of the author.

In 2002, thanks to the leadership of the Friends of Fort George and financing from interested individuals, a stone dust trail was opened from the corner of Simcoe and Front Streets across a portion of the golf course to the entrance of Fort Mississauga. This has greatly improved access to this National Historic Site that continues to suffer from the ravages of nature.

The sunrises from the ramparts are magnificent. On occasion, Parks Canada opens up the old tower for tours … a rare opportunity not to be missed.

Fort Mississauga, photo, Cosmo Condina, 2011. This view is taken from the approximate site of the 1804 lighthouse on Mississauga Point. In the foreground is the venerable tower constructed primarily from recycled bricks and stone from the burned town. Beyond is the new golf clubhouse.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.