Chapter 26

Save the Commons

Almost from the moment the boundaries of the Fort George Military Reserve were established by the colonial government in 1796, the first formal petition to encroach upon the lands was presented.[1] Many more would follow.

In January 1797 a petition was read in the executive council from thirty prominent citizens in Niagara. This was in response to a petition by William Dickson and John McFarland[2] for a portion of the southern edge of the Reserve in what is now known as Paradise Grove. The concerned citizens’ petition read in part:

… That for the well being of all residents in town, & in particular of the industrious lower classes — a range of Common or Town Parks are of indispensable necessity for pasturing Milch [sic] Cows & draft Cattle … your Petitioners humbly pray that your Honor will not permit any further Grants of the Common or Lands now used as such.…[3]

The petition for the grant was disallowed.

However, by the 1820s the colonial government was willing to give up a significant portion of the northeastern part of the Military Reserve. The change of heart was based on several factors. The threat of another war with the Republic to the south seemed remote. Moreover, the military presence at Niagara had shifted to Butler’s Barracks to the west and Fort Mississauga at the mouth of the river, and the Fort George site was being allowed to deteriorate. The military decided they required a larger defensive area around Fort Mississauga; hence the great swap occurred, whereby in exchange for his holdings at Mississauga Point, the Honourable James Crooks was granted five new blocks on the Reserve for development. There were other ongoing community issues that needed attention: the Church of England had established a community burying ground and a substantial church on Reserve land decades earlier without an actual land grant, hence the government finally proceeded with a formal grant in perpetuity. In an ecumenical gesture, the Roman Catholics were granted four acres for their parish lands. Such largesse seems to have been welcomed by all. However, when the Niagara Harbour and Dock Company petitioned for the forty acres of swampy land and water rights along the Reserve’s riverfront there was considerable grumbling both by military officials as well as local merchants. When the government hesitated, the Lieutenant Governor intervened[4] and the property passed into private hands forever.

By the mid 1830s the British government, in an effort to cut expenses, withdrew regular troops from Upper Canada and instructed local military officials to lease some of their buildings and lands. The commandant’s quarters in the middle of the Reserve were leased; lands on the Reserve were divided into ten-acre plots and were to be leased out. Mackenzie’s rebellion in late 1837 brought these plans to a crashing halt. Several British regiments were rushed back to Niagara and a building boom of military buildings at Butler’s Barracks ensued. Fifteen years later, with the threat of war or insurrection once again diminished, the British government proposed an enrolled pensioner scheme: in an effort to maintain some military presence but also reduce pensioners’ costs, veterans would be granted small two- to three-acre plots upon which they could erect a home and cultivate the land. The locals objected to this potential loss of their commons[5] and before any decision was made the military lands were transferred to the Province of Canada; the various buildings were leased out and a variety of schemes for the use of these “surplus lands” was entertained. Fortunately, all these schemes to divide up the Military Reserve/Commons fell through but it was the American Civil War and the Fenian scare that ended any further discussion to carve up the Reserve. On this occasion when the troops were rushed back to Niagara most of the leased military buildings were not available for the troops. In order to avoid a similar embarrassing experience, the new government of Canada decided to retain the lands strictly for military purposes such as summer militia camps with no thought of selling the land — at least not for half a century.

In the 1850s promoter Samuel Zimmerman extended the Erie and Ontario Railway into the town of Niagara. Initially, the plan was to run the tracks directly across the Commons to the waterfront. The government resisted and forced the railway to run along the edge of the Commons on King Street towards the river instead, as well as a spur line along the Carriage Trail (John Street East). A decade later, despite some resistance, the railway ran a spur line through the Oak Grove and forced the relocation of Navy Hall.

In the early 1880s Niagara’s postmaster, Robert Warren,[6] dreamed of establishing a summer camp similar to the American Chautauqua held annually near Jamestown, New York,[7] “under Religious, Temperance and Educational auspices, for Literary, Social and Scientific purposes.”[8] His original plan called for the transformation of his own farm on the River Road and the nearby Paradise Grove lands — which were under lease at that time by the Michigan Central Railway Company — into a campground to be known as the Fort George Assembly. After considerable discussion (but apparently no vocal citizens’ objections) the Dominion government turned down the request.[9] Instead the assembly purchased the ninety-two-acre former Crooks’ property on Lake Ontario at One Mile Creek where the Canadian Chautauqua came into being, consisting eventually of two hotels, cottages, tents, and a large four-thousand-seat amphitheatre. Although the assembly eventually failed, the Chautauqua neighbourhood still retains its unique vibrant community spirit. However, on passing through Paradise Grove today with its huge oaks and remnants of first growth Carolinian forest, one cannot help but feel very thankful for the government’s groundbreaking decision.

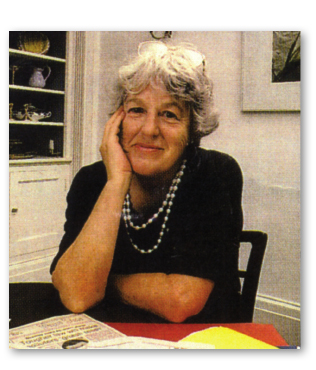

Janet Carnochan, artist E. Wyly Grier, oil, circa 1920. More than any other person, “Miss Janet” deserves credit for saving the Commons we know and appreciate today.

Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #988.246.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century there was a growing interest in Ontario’s heritage; local historical societies were being formed, often spearheaded by “spinster guardians.” Centennial celebrations of the arrival of the Loyalists in 1884 and the opening of the first parliament of Upper Canada in 1892, both held on the Commons, received much local and provincial attention. Well-attended centennial reunions for St. Mark’s and St. Andrew’s soon followed. Much of the planning and documentation for these events was due to the untiring efforts of local teacher, historian, and author Janet Carnochan. Miss Janet as she was affectionately known, was the driving force behind the formation of the Niagara Historical Society in 1895. Twelve years later, this petite dynamo proudly opened Memorial Hall, the first purpose-built museum in Ontario. Without her fearless leadership the present Commons would probably not exist today. In 1898 a successful petition to the government by Miss Janet curtailed the railway’s activities in Paradise Grove and “the Fort George enclosure.”[10] In 1905, Miss Janet learned of a federal scheme to subdivide and sell in ten-acre residential lots the Military Reserve. In her remarkable “Letter from the President of the Historical Society, Referring to the Military Grounds,” she castigates the government for having only recently spent great sums for upgrading the Fort George and Mississauga common for military purposes and for even suggesting the possible desecration of these lands:

The Pass of Thermopylae, the Plains of Marathon, the field of Bannockburn and that of Waterloo, the Plains of Abraham all rouse patriotic feelings, and the Plains of Niagara should do no less.[11]

Miss Janet then repeated a request that had been presented to the government by town officials ten years earlier,[12] in which the Military Reserve be placed in the hands of the Niagara Falls Park Commissioners and that the “ground be retained, as now, a heritage for coming generations.” The federal government quietly retreated, deciding to retain the land as a Military Reserve, thus protecting it for another fifty years. A few years later, the historical society, appalled at the state of Navy Hall, convinced the government to stabilize the building.

Old Navy Hall, photos, circa 1908. The historic commissariat building known as Navy Hall was allowed to deteriorate. Reacting to a groundswell of public indignation from historians and local townspeople, the federal government finally initiated a partial restoration.

Courtesy of the Judith Sayers Collection.

From the eve of the Great War until the return of peace in 1945, the Military Reserve served as home turf for Camp Niagara. New barracks were added and the old buildings of Butler’s Barracks were recycled for various uses. There were a few minor incursions on the edge of Paradise Grove, but for the most part the Military Reserve remained intact. After the Second World War the many surplus buildings were turned over to the War Assets Corporation for disposal. Some were moved offsite and found new uses.[13] The local population became very concerned as they witnessed several historic buildings being systematically demolished. Though strapped for funds, the Niagara Town and Township Recreational Council purchased the two old buildings in the compound as a centre for a “Boys and Girls Club” and a “Teen Town.” A local family leased a rear apartment. The council, in a desperate attempt to preserve surviving historic buildings, also obtained a lease on the ordnance gun shed, the commissariat storehouse, and the two-storey barracks. For a community deeply mired in a post-war slump, such heroic measures are truly remarkable. With resumption of the summer camps, the leases were summarily cancelled, but by then Ottawa realized that Niagara was indeed dedicated to preserving its built and natural heritage. Eventually in 1969 the Department of National Defence turned over the lands to what is now Parks Canada. The compound was reclaimed by the federal government, and together with the other three buildings they were designated as The Butler’s Barracks National Historic Site.

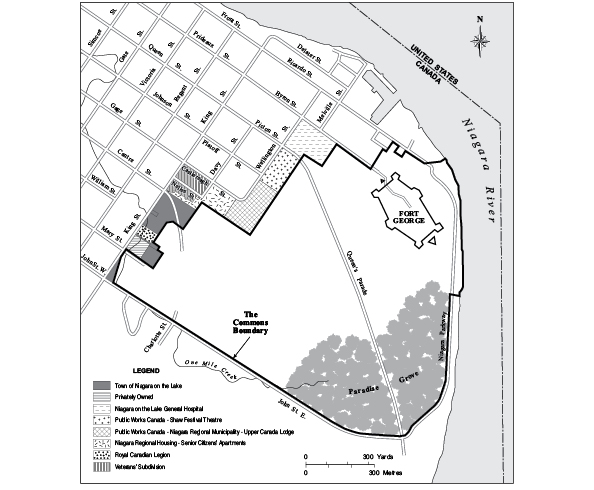

Twentieth Century Encroachments on the Military Reserve/Commons.

The overwhelming success of the Shaw Festival in the old court house soon necessitated a search for a new dedicated permanent festival theatre. Several sites were suggested but eventually attention was directed to the edge of the Commons on the corner of Queen’s Parade and Wellington. Here stood the vacated Boy Scout lodge which in turn had been the original site of the town’s baseball diamond. Initially the federal government rejected the request, but with the prospect of Camp Niagara closing the feds agreed to lease 4.12 acres. An old agreement with the Niagara-on-the-Lake Golf Club had to be retired as well. There were vocal objections to the loss of this historic corner of the Commons across from the hospital; nevertheless, the theatre opened in June 1973 and was lauded for being so carefully landscaped into its environment. Today it’s difficult to imagine the town and indeed the Commons without the Festival Theatre ensconced on that corner.

Also in the 1970s another piece of the Commons was designated for community use — a needed senior citizens’ apartment building on the site of the old fair racetrack on Castlereagh Street. How could the government have turned down such a “motherhood” project?

The one modern encroachment on the Commons that galvanized public resentment and anger more than any other project surely was the Niagara Region’s Upper Canada Lodge Nursing Home. Perched on the corner of Wellington and Castlereagh Streets on six acres of virgin commons, this 40,000 square foot complex, with an asphalt parking lot for sixty to eighty vehicles and provision for more if needed, pushed the urban space out towards the historic Indian Council House site and Otter Trail. The unique “viewplanes” across the Commons were irrevocably distorted. Although well-intentioned by some, it was soon revealed that the nursing home was not needed at that time. The Niagara Region had documented that there was a significant shortage of vacant long-term beds in the city of Niagara Falls and already an excess of empty beds in Niagara-on-the-Lake’s existing nursing home. Nevertheless, eighteen potential sites for the home were chosen in the municipality of Niagara-on-the-Lake, several much closer to Niagara Falls.[14] The vacant space of the Commons attracted the most attention. Despite demonstrations, numerous letters from heritage groups and concerned citizens, and an OMB hearing, the land was leased to the region and irreparable damage to the Commons has resulted. In the midst of the fray, an official of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board did reassure a concerned citizen that “Parks Canada will not consider any future developments of this sort on the Commons.”[15] A small comfort. The negative outcome did partially contribute to the formation of an advocacy vox populi group, The Niagara-on-the-Lake Conservancy, and taught the various heritage organizations the importance of working together whenever future threats should arise — and soon they did. Hopefully the staff, patients, and volunteers of Upper Canada Lodge today appreciate their unique location.

Margherita Austin Howe, C.M. (1921–2006). For several decades Margherita, as a concerned citizen, spearheaded various activist projects including “Operation Clean (Niagara)” for which she was inducted into the Order of Canada. As a founding director of The Niagara Conservancy she was actively involved in several attempts to save the Commons.

Courtesy of the Howe family.

The increasing popularity of Niagara as a tourist destination resulted in tremendous seasonal traffic congestion in the old town. To this end a volunteer traffic committee[16] was formed in 1988 and consultants[17] were hired to study the traffic and parking situation. The final recommendation to council consisted of extension of Nelson Street and expansion of the Fort George parking to accommodate 118 cars and twenty buses. This would result in the loss of over 250 trees and a portion of the grassy, archaeologically sensitive Commons behind the hospital. Understandably, there was much resistance to this further encroachment on the Commons: a well-received petition was circulated in town by Jim Smith, and concerned citizens and heritage organizations made presentations at a special public meeting in January 1991. Recognizing the strong public opposition to this report the superintendent of Niagara National Historic Sites advised the lord mayor that “we must consider the question to be finally and forever closed.”[18] In the midst of all the discussions one citizen suggested that in order to accommodate tourists, subterranean parking under the Commons should be considered.

Laura West Dodson, C.M. (1925–2007), photo taken at her beloved Willowbank, circa 2005. Laura worked tirelessly for several decades to preserve Niagara’s rich natural and cultural heritage, for which she was inducted into the Order of Canada. As president of the Niagara Conservancy, she was a strong advocate for the integrity of the Commons. Arguably her greatest accomplishment was the establishment of the Willowbank School of Restoration Arts in nearby Queenston.

Courtesy of Judy MacLachlan.

The strong debate over the urban boundaries for the town also focused on the Commons. If the Commons were included in the urban boundaries then any development could be approved by the town, with the agreement of Parks Canada. If outside the boundaries then any proposed development would have to be approved by Regional Council which generally is more restrictive. Today, the Commons is not within the town’s urban boundaries. Parks Canada has not permitted the Commons to be included in the town’s heritage district or the designated National Historic District citing that the Commons is already protected (see epilogue).

In 2002, another proposal was discussed behind closed doors to develop a new Shaw employee parking lot on the previously untouched grassy lands of the Commons between the Shaw Festival Theatre and the Upper Canada Lodge parking lot on Wellington Street.[19] In exchange for this piece of land that the town would develop, Parks Canada would receive ownership of a small triangle of land at King and John Street which had been the railbed for the Michigan Central Railway. A strong write-in campaign by the heritage[20] and ratepayers organizations in town as well as concerned citizenry resulted in Parks Canada withdrawing from the negotiations on the premise that the two pieces of property were not equal in size. Within six months the town was back offering, in addition to the triangle of land, the town-owned land on which was situated the Kinsmen Scout Lodge near Butler’s Barracks. Vox populi was sounded once again. The town has withdrawn its proposal — at least for now.

One spring morning the town’s citizens opened up their weekly newspaper to find on the front page an architect’s rendering of a thirty-storey office/condo tower on the Commons that was about to be approved by town council. After gasps of horror, on turning the page they realized that they had just been taken in by an April fool’s joke.[21]

As during the previous two hundred years, there will undoubtedly be more proposals for encroachments on the integrity of the Commons, many well intentioned. In fact, at the time of completion of this book in early 2012 there are two potential significant proposals[22] for the Commons itself and one overlooking virgin green common land.[23] Historians and conservationists acknowledge that there will always be a fine balance between the preservation of this special verdant place and the forces for change that are inevitable in a dynamic community. Hopefully this humble volume will inspire future generations to protect the integrity of the Commons.