Chapter 8

Fort George on the Commons

Bitish government officials knew they would eventually have to give up Fort Niagara to the Americans, as stipulated in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Within one year, Governor Haldimand had directed his surveyors to reserve the open ground to the west and south of Navy Hall for a military “post.”[1] By 1791 the land had been staked out for a future fortification,[2] but it was another five years before the imminent British evacuation of Fort Niagara forced the start of construction of the new post. This portion of the Military Reserve/common lands was now officially off limits to the townsfolk.

The detailed story of the evolution, demise, and eventual resurrection of Fort George is better told elsewhere[3] ; however, with the encircling grassy open plain of the Commons providing a clear, unobstructed view of an approaching enemy both by land and water, the Commons was always strategically an important component of the fort. Hence, an abbreviated history of the fort and its garrison is warranted.

The British Royal Engineers chose the site above Navy Hall because it was fourteen feet higher in elevation than Fort Niagara, an important consideration when one attempts to lob artillery shells onto an enemy’s fortifications. However, this slight advantage was easily overcome by the Americans who established a battery on the river bank directly opposite, which happened to be slightly higher than the west bank. (As a counterpoise, the British later constructed the crescent-shaped Half-Moon Battery on the riverbank, south-east of the fortifications.[4] ) More importantly, being situated 1,100 yards upriver, the new fort could not control the mouth of the river. This strategic disadvantage was quickly recognized by the military officers during the War of 1812, and only ameliorated by the construction of Fort Mississauga, which was not completed until the 1820s.

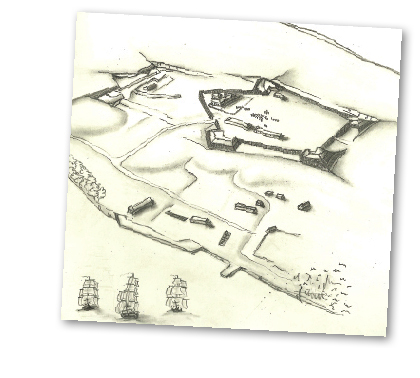

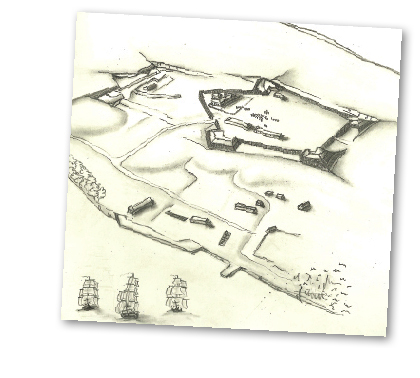

Bird’s-eye view of Fort George from the east, 1805, artist Tiffany Merritt, graphite on paper, 2011. This is a conjectural drawing showing the six earthen bastions connected by palisades enclosing soldiers’ barracks and a large officers’ quarters. The stone powder magazine is within the fort. Terrain of the fort’s interior is still somewhat uneven.

Drawing based on conjectural drawings in an unpublished report. Gouhar Shemdin, David Bouse, “A Report on Fort George” (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1975). With permission of Parks Canada.

With the improved prospect for peace between Upper Canada and the United States in 1796, all regular British troops were withdrawn from the colony, leaving only the Queen’s Rangers, who were mainly assigned elsewhere, and the Royal Canadian Volunteers — all recruits from the province. The second battalion of this provincial regiment was assigned to Niagara for defence and to undertake the construction of the new post. Initially, the new “fort” consisted of a few scattered rudimentary buildings on the heights above Navy Hall. Those included a small blockhouse/barracks for the Volunteers, a stone powder magazine,[5] and two small warehouses,[6] all apparently completed by 1796. However, by 1799, more in response to concerns of a Native uprising than American intentions, the site had undergone a major transformation with construction of six earthen and log bastions linked by a wooden twelve-foot palisade eventually surrounded by a dry ditch.[7] Inside the palisade a guardhouse, five log blockhouses/barracks, a hospital equipped with sixty beds available for both military and civilian patients, kitchens, workshops, and spacious officers’ quarters were constructed. The Volunteers laboriously accomplished all the quarrying of stone, felling of trees, hewing of timber, excavation of the ditches, erection of the palisades, plus the construction of all the buildings. With the work completed, the regiment was disbanded in 1802, their garrison duties taken over by the 41st British Regiment of Foot.

In the year 1800 a traveller reported, “The situation is pretty … the fort new and remarkably neat, built on the edge of a handsome green or common.”[8]

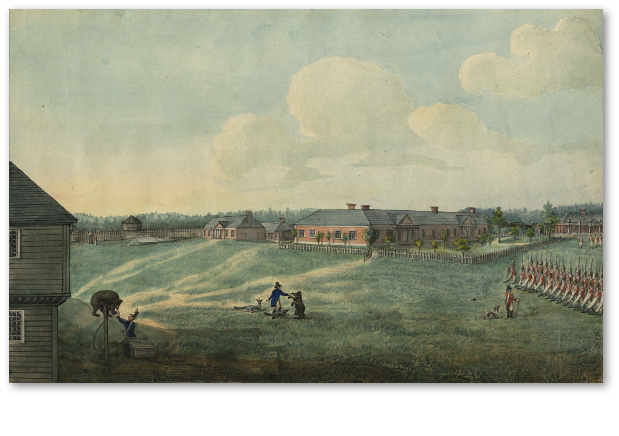

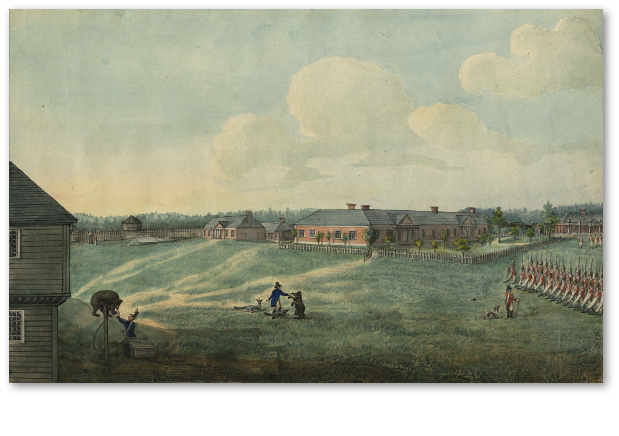

The Esplanade, Fort George, Upper Canada, artist Edward Walsh, watercolour, circa 1805. Note the somewhat uneven terrain of the parade ground. In the centre, the artist has incorporated himself holding a fox on a leash and possibly feeding one of the bear mascots of the 49th Regiment.

William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

During the first decade of the nineteenth century, tensions between Great Britain and the United States escalated. Just before the outbreak of hostilities in June 1812, Major General Brock and his staff apparently concluded that Fort George, headquarters of the Central Division of the British Army in Upper Canada, was too large to defend. Plans were drawn up to reduce the fort’s size by one third, abandoning the two southern bastions, the octagonal blockhouse, and the stone powder magazine, and building a palisade “curtain” across the southern exposure of the fort.[9] It is not clear how much of this work was completed by the British before the American invasion in May 1813.[10]

We do know that in early October 1812 Brock had supervised the strengthening of the strategic northeast “York” bastion, apparently so named by Brock in recognition of the York militiamen who had laboured strenuously towards its completion.[11] Within a fortnight both he and Macdonell would be buried in this same bastion, known as the Brock bastion ever since.

Early in the morning of the ill-fated American invasion at Queenston in October 1812, Fort Niagara’s artillery shelled Fort George using red hot shot as a diversionary tactic. These superheated cannon balls ignited several wooden buildings within the fort. One month later more buildings were set on fire by a similar bombardment. But it was not until May 1813, as a prelude to the successful American invasion, that virtually every wooden building within the fort was destroyed by horrendous and incessant artillery fire from both land and shipboard batteries (see chapter 10).

The Battle of Fort George concluded with the abandonment of the fort and the retreat of the combined British forces towards Burlington. The occupying Americans immediately strengthened the fort’s southern flank by constructing a new major bastion of earthworks and palisades. They eventually threw up extensive earthworks extending from the northwest bastion as far as St. Mark’s cemetery (where remnants can still be traced today) and then eastward towards the river’s edge.[12] No new buildings were erected by the Americans inside the fort during their occupation. The Americans established several small outlying posts, or “piquets,” within a mile or two of the fort. Similar British piquets lay beyond. There were multiple skirmishes across this no man’s land throughout the summer and early fall. Taking part in these skirmishes on the side of the Americans were two new groups of combatants.

Bird’s-eye view of Fort George, 1812 from the east, artist Tiffany Merritt, graphite on paper, 2011. By the fall of 1812 or early the following spring, the Royal Engineers were directed to truncate the fort, abandoning the two southern bastions and stone powder magazine with wooden palisades across the southern exposure. The soldiers’ barracks were also to be reduced in height. It is not clear how much of this work was actually accomplished.

Drawing based on conjectural drawings in an unpublished report. Gouhar Shemdin, David Bouse, “A Report on Fort George” (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1975). With permission of Parks Canada.

Bird’s-eye view of Fort George, 1814 from the east, artist Tiffany Merritt, graphite on paper, 2011. During their occupation the Americans greatly fortified Fort George with stronger earthen bastions, including earthworks extending across the southern half of the truncated fort as well as earthworks extending from the northwest bastion towards St. Mark’s burying ground. They apparently did not erect any significant buildings within. Upon recapture by the British in late 1813, new log barracks and possibly a brick/stone inner powder magazine were erected.

Drawing based on conjectural drawings in an unpublished report. Gouhar Shemdin, David Bouse, “A Report on Fort George” (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1975). With permission of Parks Canada.

For the first time in the war “volunteer”[13] Native Americans were fighting on the Canadian side of the river, often in direct confrontation with their cousins, the Grand River Six Nations, a pivotal event in Iroquoian history.

Also fighting with the Americans were the “Canadian Volunteers.” One-time member of the House of Assembly, newspaper publisher and citizen of Niagara Joseph Willcocks[14] convinced American General Dearborn at Fort George in July 1813 to allow him to establish a corps of disaffected Canadian volunteers to fight alongside the American army in Upper Canada. As such, the Canadian Volunteers are the only military corps to be actually raised at Fort George.

Six thousand American soldiers, their Native allies, and the Canadian Volunteers were encamped in tents on the plains outside the fort behind the new trenches. They were much decimated by disease,[15] desertion, and eventual redeployment elsewhere. One disgusted American General reported:

We have an army at Fort George which for two months past has lain panic-struck, shut up and whipped in by a few hundred miserable savages leaving the whole of the frontier, except the mile in extent which they occupy, exposed to the inroads and depredations of the enemy.[16]

By December there were only sixty remaining occupying troops that happily returned to American soil, but not before they torched the town of Niagara. Surprisingly, the fortifications and the Americans’ pitched tents were left intact although, according to one observer, no barracks were left standing.[17] When the British reoccupied the fort the rebuilding process began once again: two log barracks for three hundred men, a small frame quarters for officers, and possibly a new stone/brick powder magazine[18] within the fortifications.

During the summer of 1814, after the American success at the Battle of Chippawa, the American army laid siege to Fort George and dug trenches on the Commons. Years later, a young U.S. drummer recalled an incident on the Commons during this abbreviated siege. Their commander, Colonel Winfield Scott,[19] was sitting on his horse a few yards in front of the American line, when suddenly a whistling sound was heard coming from the fort’s artillery (probably a howitzer). Scott calmly held up his sword to sight the incoming shell, concluded that he was vulnerable, and immediately wheeled his charger to the side just before the shell landed on the very site he had been occupying seconds before.[20] Despite this one inspiring moment, the Americans, having waited in vain for promised naval support, withdrew after only a few days.

After the war, realizing the shortcomings of the Fort George site, all efforts were directed to building Fort Mississauga (see chapter 23) at the entrance to the Niagara River and the new Butler’s Barracks (see chapter 11) at the westerly end of the Military Reserve, out of clear range of American artillery. Initially, some troops were still quartered in the old log barracks within the fort. Both surviving powder magazines served as supply depots for the Royal Artillery stationed at Fort Mississauga.

In 1817, while on a good-will tour, the President of the United States, James Monroe was entertained with great civility by British officers somewhere in the historic Fort.[21]

By 1825, however, Fort George was reported to be “in ruins.”[22] The bodies of Brock and Macdonell, buried in 1812 with great ceremony in the Northeast Bastion (now known as the Brock bastion), were disinterred and reburied in the base of the first Brock’s Monument at Queenston Heights. British military headquarters were moved to York, much to the annoyance of the locals. By 1839, the remaining soldiers were using the rebuilt Navy Hall complex as their barracks while the old barracks within the fort were downgraded to stables. Some of the adjacent Military Reserve was granted to merchant James Crooks in exchange for his strategic lands at Mississauga Point (see chapter 12).

In November 1844, Lieutenant Colonel R.H. Bonnycastle of the Royal Engineers received an unusual request from Mr. Edward Campbell of Niagara to purchase a ten-foot square of land on the southwest bastion of Fort George. Campbell claimed that he was the eldest son of Donald Campbell who had served honorably as Fort Major of Fort George until his untimely death in December 1812. Apparently he had been buried near the southwest bastion and his son wanted to erect a memorial on the site. Although the Board of Ordnance approved the request it is not known whether the son ever erected a cairn.[23] He may have changed his mind, as a large memorial plaque for the Fort Major is situated inside St. Mark’s Church “Erected By His Eldest Son 1848.”

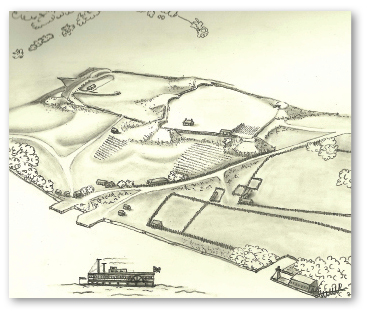

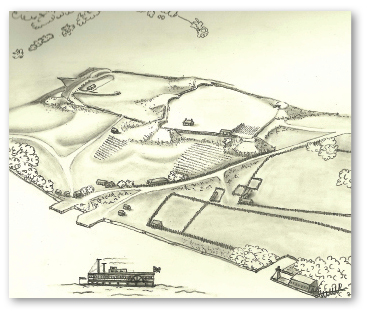

Bird’s-eye view of Fort George, 1880s, artist Tiffany Merritt, drawing, graphite on paper, 2011. By the 1880s the bastions were deteriorating as well as both powder magazines. The 1816 officers’ barracks was occupied by a custodian and some of the land both inside the fort and on the outer earthworks was being cultivated.

Drawing based on conjectural drawings in an unpublished report. Gouhar Shemdin, David Bouse, “A Report on Fort George” (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1975). With permission of Parks Canada.

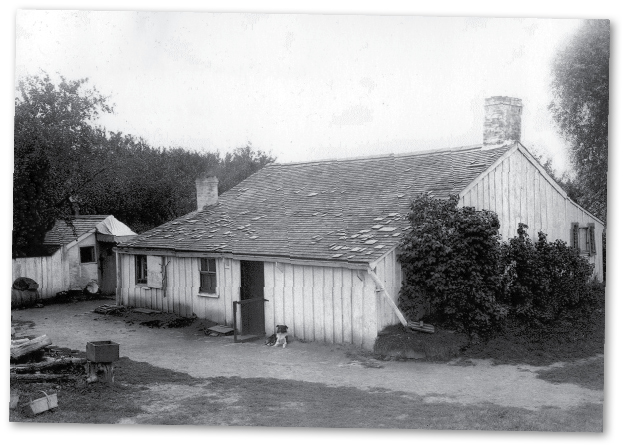

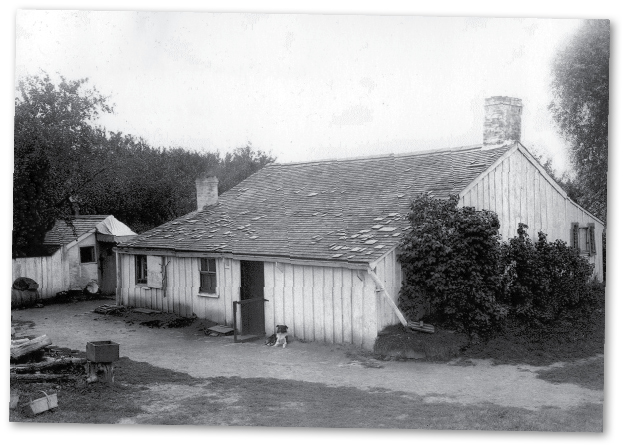

With the Fort no longer a military installation, the eight-acre parcel of land was leased intermittently to private citizens, including John Meneilly in the 1840s and ’50s and later the Wright family from 1882 until the eve of the Great War. Rent was sixteen dollars per annum. The small officers’ quarters (circa 1814) was incorporated into a larger farmhouse, while the esplanade was cultivated as a garden and used for grazing animals. The original stone powder magazine was intermittently occupied by squatters or used for the storing of hay. The townsfolk’s livestock grazed on the grassy bastions and youngsters played “fort” or dug for artifacts on the slowly eroding earthworks. One former student of schoolmistress Miss Janet Carnochan recalled being excused for “habitual tardiness or failure in [his] studies” by bringing in regimental buttons he had found while “ransacking the dust heaps of Fort George.” A found military cross-belt plate atoned for major truancies.[24]

In 1897 a Toronto newspaper reporter described the pastoral vista.

A visitor naturally asks on approaching the Commons from the town, where is Fort George? He is pointed to a grassy hillock surmounted by a grand old tree [the Lonely Sycamore]. A nearer approach shows the grassy depression compassing the old earth works that did service in the moat. Here, where once the murky cloud from cannon dulled the sunlight, a little streak of blue smoke rises from a small frame homestead nested in the heart of the old fortifications. The ruins of the magazine are there. Strong and massive in those days long ago; if the cow is out you can enter and look around.…[25]

The Wright Cottage, photo, circa 1910. For over one hundred years the interior of Fort George was intermittently leased to custodian-tenants, the Wright family being the longest occupants. The cottage incorporated the small 1814 officers’ barracks and was eventually restored as such in the 1930s.

Private collection.

However, such a peaceful scene belied a major controversy. In the 1880s a golf club had laid out a nine-hole course on a portion of the ruins and adjacent Commons. By 1895 it had expanded to eighteen holes and a total distance of over five thousand yards. Janet Carnochan, herself a daughter of Scotland, described the unique course so eloquently:

… surely never had the players of the game such historic surroundings. The very names of these holes are suggestive of those days when, instead of a white sphere, the leaden bullet sped on its way of death or the deadly shell burst in fragments to kill and destroy. The terms used in describing the course — Rifle Pit, Magazine, Half-Moon Battery, Fort George, Barracks — tell the tale.[26]

The club, whose membership was predominately American summer residents, proposed cleaning up the old fort site and erecting a clubhouse within. Increasingly impassioned letters to the editor and editorials in the local and Toronto newspapers referred to the desecration of sacred heroic sites as a sellout to “Sabbath-breaking Americans,” while others countered “predatory bovines now wander at their sweet will through the bastions, the inner court is used as an oat field … A five minute ramble serves to cover one to the elbows with burs, and this is the place that patriotic ‘Canadian’ wishes to save from desecration!”[27] Surprised and bewildered by the opposition of the townsfolk, the golf club quietly abandoned its plans (see chapter 20).

In 1912 Robert Reid, a former local chief of police, was hired as caretaker of Fort George by the Department of National Defence. He undertook an aggressive cleanup of the site, and by the following spring the local newspaper exclaimed, “a wondrous change has taken place.”[28] The locals once again were enjoying the “ruins” on the Commons, but soon all would change. With the outbreak of war in 1914, Camp Niagara on the Commons was thrown into high gear (see chapter 14). The Wright’s lease was not renewed and the Fort George golf links were closed. The southern portion of the fort’s former esplanade was soon the site of a fifty-bed military hospital complete with one fully equipped operating room. It was officially opened by Lady Borden, wife of the Canadian Prime Minister. Several other auxiliary buildings were erected, including a mess, kitchens, guardhouse, and toilets.

With the end of the Great War the buildings within the ruins sat unused, but the site was finally beginning to attract some recognition from historians and politicians. The newly formed Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada dedicated a stone cairn on the site to recognize the importance of Fort George. To provide better public access to the site a road was built in 1931 from the Niagara Parkway’s intersection with John Street northwards along the river and then skirting the western edge of the ruins to connect with the end of Byron Street. (The portion skirting the fort was removed in 1990 and replaced by the Recreation Trail.) Seven years later the Parkway was also extended down to Navy Hall to connect with Ricardo Street.

In the mid 1930s, with Canada in the depths of the Depression, the federal and provincial governments were looking for make-work projects. The Niagara Parks Commission (NPC) proposed to the Department of National Defence that they would undertake the restoration/reconstruction of Forts George and Mississauga, as well as Navy Hall, if they were granted a ninety-nine-year lease for a nominal one dollar per annum. The offer was quickly accepted, but with some stipulations. To be eligible for federal funding preference would have to be given to workmen who were presently unemployed and married with dependants, they should be from the area, and the work should include as many workmen as possible. The Department of National Defence, mindful of past experience, also reserved the right to reclaim the lands with six months notice.

The two men who were instrumental in the eventual success of this ambitious undertaking were the Honourable Thomas McQuesten and Ronald Wray. McQuesten was chairman of the NPC as well as Minister of Public Works and Minister of Highways. An overachiever, this tireless visionary proposed and supervised many similar restoration projects and was the driving force behind the Queen Elizabeth Way superhighway and the Niagara River Parkway. Wray was the project historian and director of all the Niagara projects. Considered one of the historical restoration experts of the time, he was also in charge of the Fort Henry restoration in Kingston at the same time. Despite frequent commutes between Niagara and Kingston, Wray found the time to court and marry a local Niagara girl.[29]

After considerable archival research but no archaeological survey,[30] the decision was made to reconstruct the fort to its original 1799 layout. A careful survey of the site was not easy:

A century of erosion had reduced the earthworks to little more than five or six feet above the overall level of the site. In some places they were barely discernible at all … The survey … went slowly due to the almost impenetrable growth of brush and thorns which again covered the earthworks.[31]

Work began on Navy Hall in August 1937. A few weeks later a Michigan Central freight train came puffing and hissing down the King Street tracks carrying heavy excavating equipment. Such was the announcement to the sleepy little town that work was soon to start on Fort George as well. The initial restoration and reshaping of the earthworks using bulldozers took several months.[32] Only the two northern bastions had retained any semblance of their original configuration. The military hospital, mess hall, kitchens, and one caretaker’s cottage were relocated to the edge of Paradise Grove. The original 1796 stone powder magazine, particularly its interior brick lining, was in very poor shape but was eventually completely restored. The small officers’ quarters (1814) was moved to a new location[33] and restored to its presumed original appearance. All the timber for the fortifications was pressure creosoted for longevity. They lasted until 2010.

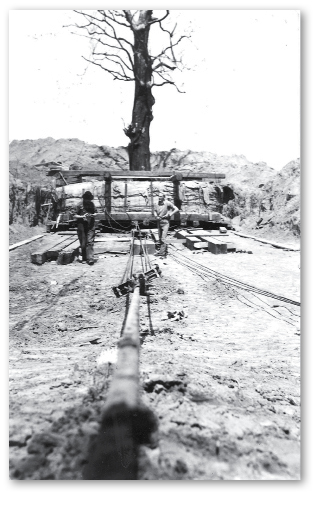

As previously described, much of the long-neglected site had become overgrown with trees of various sizes, all of which were cut down with one exception: a giant sycamore (buttonwood) tree some eighty feet tall standing as if on guard on the edge of the northeast (Brock) bastion. There was great public concern for this beautiful and impressive “Lonely Sycamore” that had become part of local lore, a favorite venue for family picnics, and praised both in prose and poetry.[34] An heroic and monumental effort[35] was made to move this landmark, which weighed an estimated one hundred tons, under the supervision of students at the Niagara Parks Commission’s School of Horticulture. In May 1939 the tree was replanted in a new location just outside the northwest bastion. The tree seemed to be viable at first, but with each succeeding spring it sprouted fewer and fewer leaves, and finally the Lonely Sycamore succumbed. A small rise in the turf near the bastion marks it final spot.

In the spring of 1939 the second phase of Fort George’s phoenix-like rise began. After the stone foundations had been completed, the fort’s lost buildings were reconstructed based on the research available at that time. All the timber used came from a first-growth white pine forest in northern Ontario.[36] Many of the logs were so immense that they had to be hand-cut by whipsaw on the site. The pit used for this laborious work remains evident inside the fort today. All exposed wood surfaces were fashioned using early hand tools. Soon, all the present buildings on the site were erected. The massive front gates were the last to be completed. A log “Trading Post” was built as a reception centre well outside the fort’s reconstructed perimeter.

The first official visitors to the fort never stepped inside. In June 1939, Niagara-on-the-Lake was included in the Royal Visit by King George VI[37] and his consort Queen Elizabeth.[38] As the Royal cavalcade proceeded along the road skirting the western flank of the fort, three thousand excited school children cheered and waved their flags. Even the recently transplanted Lonely Sycamore bravely showed its leaves.

With the work finally completed, plans were underway for a gala opening party. The restored Fort Niagara across the river had enjoyed a grand celebration in 1934, as had Fort Erie in 1939. But Canada was now in the midst of another world war and the NPC decided that such a party was not appropriate. The gates quietly opened to the public on July 1, 1940. There was even concern that the Department of National Defence might exercise its right to reclaim the fort site for military purposes. Much to the relief of local officials, the fort itself was not needed as part of the war effort. In fact, for the tens of thousands of service men and women training on the Commons at Camp Niagara, the fort became a gentle reminder of their rich military heritage.

St. George’s Lonely Sycamore at Fort George Heights, Niagara, photo, circa 1890. The eighty-foot tall Lonely Sycamore stood proudly near Brock’s Bastion. A favourite picnic spot, it inspired patriotic prose and poetry.

Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, T 13478.

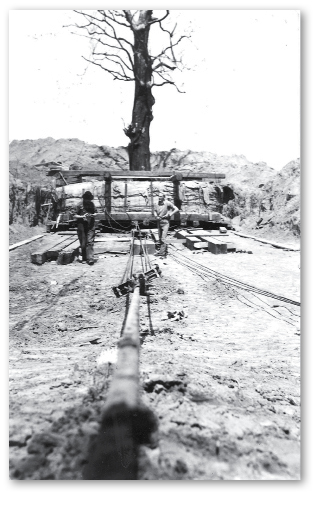

Moving the Lonely Sycamore, photo, 1938. This was the largest known tree removal of such a mature tree attempted at that time. The huge root was balled and burlapped. Under the careful supervision of students from the newly inaugurated Niagara Parks School of Horticulture, the tree was pulled through a timber-lined trench to its new site outside the fort.

Courtesy of the Niagara Parks Commission Archives.

Finally, in June 1950 the official opening and dedication of Fort George was held in the presence of ten thousand spectators with marching bands and a cross-border exchange of cannon salutes. Festivities were capped off with a very twentieth-century phenomenon — a stirring fly-past by American and Canadian Air Forces. Initially Fort George was operated as a passive museum with displays of military artifacts in the blockhouses. A custodian lived on the premises (the site of the garrison hospital in the original 1799 fort). In 1969 the ninety-nine-year lease was broken and the NPC officially transferred ownership of the site to the federal Parks Canada. Navy Hall and Fort George were named a “National Historic Park.” Reflecting changing attitudes about museums, Fort George became a “living history” site with emphasis on interpreting the garrison on the eve of the War of 1812 with live demonstrations of various aspects of garrison life, including the soldiers and camp-followers.

Bird’s-eye view of Fort George, 1950, artist Tiffany Merritt, graphite on paper, 2011. Although not exactly as it was originally built, the restored Fort George captures the essence of the original fort as a living museum.

Drawing based on conjectural drawings in an unpublished report. Gouhar Shemdin, David Bouse, “A Report on Fort George” (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1975). With permission of Parks Canada.

To accommodate increased visitation, a larger parking lot was carved out of the Commons to the west and north of the fort site, partially camouflaged with berms and a newly planted small forest of native trees. Part of the American earthworks and campsite (1813) and possibly an American soldiers’ burial site may lie under the northeast edge of the parking lot, the bush, and the grassy fields beyond, along Byron Street.

One question often posed by visitors to Fort George today concerns the accuracy of the restoration. If Brock were to march into the fort today he would probably be very surprised by the expansive flat esplanade in the middle of the fort. Early maps and an 1805 interior drawing of the fort[39] as well as later sketches of the fort “in ruins” indicate a somewhat uneven terrain of the interior grounds, possibly due to old dried up creek beds that are still evident in other parts of the Commons. The 1930s bulldozers reforming the earthworks simply flattened out the fort’s interior space. Brock would note that the reconstructed guardhouse is not on its precise original site; the three blockhouses are not quite accurate as the new blockhouses were based on surviving contemporary blockhouses at Fort York in Toronto. He would be pleasantly surprised that there is now a tunnel to the octagonal blockhouse. Some of these discrepancies can be blamed on the lack of any archaeological assessment and the limited research resources available to the restoration historians. Nevertheless, on spending a couple of hours inside Fort George today, one is faithfully transported back in time to a period when Upper Canada’s military survival was very much in doubt.

With paid admission to the site, this portion of the Military Reserve/Commons became no longer readily accessible to the townspeople as “common lands.” After the restoration, it was as if there were two unwritten solitudes: the restored museum-fort — run by the NPC with its own live-in custodian and a few locals who worked in the Trading Post — and the townspeople who were for the most part indifferent to Fort George. On occasion locals were invited to special events within the fort. This attitude changed with the formation in 1987 of the Friends of Fort George, an association of interested and concerned local citizens. The Friends is dedicated to encouraging awareness and appreciation of Fort George and its artifacts and to support Parks Canada’s mandate to protect, preserve, and interpret the military significance and historical resources of Fort George and its surroundings (including the Commons). Primarily as a result of the Friends’ efforts many local citizens have become involved in the activities of the fort as volunteers and re-enactors. Funds raised by the Friends through their gift shops and other activities have been used by the permanent staff to hire more well-trained interpreters for the fort and to develop new programs such as the excellent period military fife and drum corps.

For over twenty years the Canada Day Committee, of which the Friends is an important partner, has celebrated Canada’s birthday with a list of fun events, including breakfast and lunch in Simcoe Park, entertainment in the bandshell, and the grand parade of the birthday cake. In the evening the gates to Fort George are thrown wide open to welcome one and all. Citizens and visitors of all ages and backgrounds stream in, open up their lawn chairs, and spread out their blankets on the grass of the esplanade and sit back and enjoy the camaraderie of the long summer evening, the period music, the short historical vignettes, and then the fireworks (a faint echo of the cannon rumblings and Congreve rockets of so long ago). For a few precious hours the locals and their guests have reclaimed this special place as their “common lands,” their land to enjoy in common.