Hitler’s Rise to Power

Adolf Hitler, an ardent fan of composer Richard Wagner, the French writer Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, and the British-born writer Houston Stewart Chamberlain, all early proponents of Nordic supremacy and anti-Semitism, believed that Germany was preordained by God to be a world power. He also believed that the nation had become poisoned by what he considered “foreign elements” and inferior races (particularly the Jews), and that they were the reason for the nation’s lowly position after World War I.

Hitler had been a soldier during World War I, volunteering for a Bavarian unit in the German army and serving through the entire conflict. It was during this period that Hitler’s anti-Semitism grew into the demented brand of nationalism that eventually made him one of the most reviled leaders in world history.

After the war, Hitler joined the German Workers’ Party, which he eventually led. He later changed the party’s name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, from which the word Nazi (German acronym for National Socialist) was derived, and borrowed the swastika as the group’s defining symbol. Many of Hitler’s followers were members of the Free Corps—supposed freedom fighters and foes of socialism who often took the law into their own hands, settling disputes with violence. By 1923, the organization boasted nearly 70,000 members.

Germany in Disarray

In the years after World War I, Germany fell deeper and deeper into chaos. By late 1923, its economy had bottomed out, making the German currency, the mark, virtually worthless. This is exactly the kind of environment in which dictators are born, and Hitler knew it. On November 8, he tried to incite a revolution against the Bavarian provincial government during a rally of monarchists and nationalists. Though his efforts resulted in nothing more than a small riot that was quickly put down by armed police, Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch became famous. He was sentenced to five years in prison but served only nine months.

Adolf Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), was written while he was imprisoned at Landsberg am Lech for his failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. In the book, Hitler details his life and philosophy. Much of it is anti-Semitic, claiming that the Jews were responsible for all that was wrong in Germany.

When he was released, Hitler was more intent than ever on assuming power in Germany. The Germans needed help—they were barely surviving, their national pride in tatters. They needed an explanation, they needed self-assurance, they needed a common cause and a common scapegoat, and Hitler gave them what they asked for. He portrayed himself as the father figure that Germany so desperately needed. All the nation’s problems, Hitler told his followers, resulted from unsavory influences and the poisoning of Germany’s racial purity. As the years went on, Hitler’s closest advisers and confidants came to include Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels, all of whom would later help Hitler lead the nation into one of the most barbaric periods in human history.

Hitler’s original title for Mein Kampf was “Four and a Half Years of Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice.” It was his editor who suggested a title change.

In the 1932 election, Hitler made his first important step toward his goal of assuming power in Germany. Indeed, his timing couldn’t have been better. The established coalition between socialists and middle-class parties in the Reichstag, the German parliament, had been all but destroyed by the Depression, opening the door for new leadership. In April, the Nazi Party won control of four state governments, and Hitler finished a distant second (with only 37 percent of the popular vote) after conservative president Paul von Hindenburg. Centrist chancellor Heinrich Brüning, who had grown increasingly unpopular as a result of the austerity measures he had imposed on the already suffering nation, resigned as a result of the election; his successor, Franz von Papen, called for Reichstag elections in July.

Nazis Consolidate Power

Spurred by Hitler’s growing popularity, the election gave the Nazis 230 seats, making the party the largest and most influential in the Reichstag. The Nazi delegates, recognized by their brown uniforms, acted more like bullies than legislators, and debates with opposing delegates usually turned into brawls. Meanwhile, the nation’s political conflict poured into the streets as Nazi storm troopers engaged Communist paramilitary fighters in almost nightly battles.

Hitler Rises to Power

Chancellor Papen hated the Nazis but needed their support to govern, so he reluctantly extended the hand of partisan friendship by offering Hitler the position of vice chancellor. But Hitler refused, demanding the chancel-lorship. A panicked Papen tried to bolster his own position by dissolving the Reichstag and calling for fresh elections again in November. The Nazi Party lost thirty-four seats but still retained its superior position.

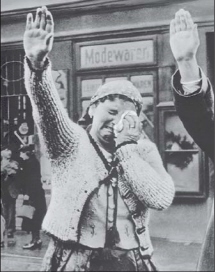

Figure 1-1 A Sudeten woman weeps as she is forced to salute Hitler in 1938.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (208-PP-10A-2)

Papen tried briefly to convince Hindenburg to declare his own dictatorship in a desperate bid to keep Hitler from power, but both men quickly realized that such a move would be foolhardy because of the strength and number of Nazi storm troopers and because too many of the nation’s military officers supported Hitler. Hindenburg dismissed Papen and replaced him with Defense Minister Kurt von Schleicher, who then offered the position of vice chancellor to the leader of the Nazi Party’s left wing. However, the gesture only served to unite party members more strongly behind Hitler.

What were the three reichs?

According to Hitler, the First Reich was the Holy Roman Empire, a group of Germanic tribes united by Charlemagne in the ninth century. The Second Reich was Germany unified under Otto von Bismarck and carved up after World War I. Hitler proclaimed the inauguration of the Third Reich, which he said would conquer all of Europe and last 1,000 years.

After failing to form a government with either the socialists or the conservative nationalists, Schleicher resigned as chancellor on January 23, 1933. Both he and Papen remained powerful members of the Reichstag and had convinced themselves that if they couldn’t keep Hitler out, they could at least control him by surrounding him with more moderate cabinet ministers. After a frenzy of negotiations, Hitler became chancellor on January 30, 1933.

However, Hitler was not about to be appeased. He and his followers quickly set to work making him supreme and absolute ruler of the German republic by brutally eliminating all who might oppose him politically and making friends with the rich industrialists whose support Hitler desperately needed. When the long-ailing Hindenburg finally died on August 2, 1934, Hitler quickly abolished the office of president and with the cry “One race, one realm, one leader!” proclaimed himself der Führer—the Leader.

Fascism Takes Hold of Italy

Yet another match was held to the fuse that would ignite World War II with the rise of Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini. A former newspaper editor and a gifted orator, Mussolini fanned the fires of political nationalism by convincing his beleaguered countrymen that Italy had emerged victorious from World War I. In truth, the sections of Austria that ended up under Italy’s control had been given to it as part of several secret agreements and were not the result of military might. Nonetheless, the Italian people, swollen with national pride, took Mussolini’s words to heart.

Mussolini also capitalized on the attempts by Communists to seize control of Italy after the war. With many people starving and the economy still in shambles, the Communists thought their timing was perfect for another “people’s revolution” and instigated a number of strikes and shutdowns. Prime Minister Francesco Nitti, shaky and unsure of how to react, opened the door to a Communist takeover.

In March 1919, Mussolini and several other war veterans formed the Fasci di Combattimento, a right-wing, anti-Communist movement that quickly swept the country. Wearing signature black shirts, Mussolini’s Fascist militia did all it could to strengthen national pride while dismantling labor and socialist groups—often with violence.

In 1922, Mussolini’s followers stormed Rome, intimidating King Victor Emmanuel III into offering Mussolini the position of prime minister in what was supposed to be a coalition government. It was then that Mussolini adopted his famous title of Il Duce—the Leader.

Within four years, Mussolini turned the supposed coalition government into a dictatorship with himself at the helm. Thus, his rise to power was complete. Even though many personal freedoms were gradually withdrawn, including the right to strike, Mussolini managed to preserve some aspects of capitalism and expand social services. He also ended decades of conflict with the Vatican by signing the Lateran Pact of 1929, a compromise that recognized Rome as the capital of Italy but granted sovereignty to the Vatican.

Once Italy was in his grasp, Mussolini, like most dictators, began looking to expand his empire with an aggressive foreign policy. First to fall was Ethiopia, which Italy conquered in 1935 and 1936 despite protests from the League of Nations. Though condemned by the international community, the conquest was celebrated by the Italian people, and Mussolini’s popularity skyrocketed. He soon decided to align Italy with Nazi Germany in what became known as the Axis.

Japanese Aggression

Ruled by an emperor but controlled by militarists, Japan—desperate for raw materials—was ready to continue the expansion it had started nearly forty-five years earlier with the acquisition of the island of Burile, the Bonin and Ryukyu Islands, and the Volcano group. In war with China in 1894 and 1895, Japan took Formosa (now Taiwan) and the Pescadores. Soon afterward, it seized Port Arthur and the southern half of the island of Sakhalin from Russia and took control of Korea, which it officially annexed in 1910. After World War I, Japan received mandates over the Marshall, Caroline, and Mariana Islands, which had formerly belonged to Germany.

Following the Naval Disarmament Conference of 1920, which weakened the American and British presence in the Pacific, Japan strengthened its powerful navy, fortified its mandates in violation of international treaty, and set its eyes on China while conditioning its people for the inevitability of war.

American Isolationism

The United States was condemned on many fronts for dragging its feet in entering World War I, but in truth the nation’s isolationist policies were as old as the republic itself.

America’s first political leaders encouraged commercial treaties and expansion of trade with other nations but discouraged political or military alliances because of their inherent dangers. One such view was expressed by George Washington, who in his 1796 farewell address advised the nation that he had helped to promote good relations with all the world’s countries, particularly in regard to trade, but warned strongly against becoming involved in Europe’s complicated and ever-changing political affairs.

The United States maintained an isolationist attitude for many years, preferring to expand into the sparsely populated land that spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific rather than become involved in global politics. Such an attitude also helped protect the fledgling country from European domination— always a risk when dealing with older, more established nations.

With only a few exceptions, isolationism remained a steadfast policy throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. When hostilities finally broke out in Europe in 1914, the United States assumed a stance of neutrality, despite the fact that many of its most important economic allies were fighting for their lives.

The war raged for nearly three years before U.S. troops went to Europe in the spring of 1917, provoked by attacks on merchant ships by German submarines. American anger was aggravated by the discovery of what became known as the Zimmerman note—a secret message from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmerman to his ambassador in Mexico City, instructing him to offer Mexico financial aid in exchange for an invasion of the United States. Declaring that, “the world must be made safe for democracy,” President Woodrow Wilson finally asked Congress for a declaration of war. The United States entered World War I four days later.

At the war’s conclusion, America once again put up an isolationist wall. Even after just one year, the country had grown weary of fighting overseas and the Red Scare at home, and wanted nothing more to do with international politics. The men who served as president after World War I understood this sentiment and did all they could to keep the nation out of conflict. As President Warren G. Harding noted, the nation needed “not submergence in internationality but sustainment in triumphant nationality.”

The League of Nations was established in 1920 in an effort to make sure another world war would never happen. Though the League was suggested by President Woodrow Wilson, the United States did not join. The U.S. Senate, angry over being left out of treaty negotiations by Wilson, and concerned about congressional war powers, refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, which governed the League’s covenant.

Isolationism Following the First World War

President Calvin Coolidge, who assumed office after Harding’s death in 1923, maintained his predecessor’s position of international neutrality, preferring to concentrate on the growth and maintenance of his own country. The only issue that managed to penetrate the nation’s staunch isolationism was the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which the United States signed along with sixty-one other countries, including Germany, Japan, and Italy. In so doing, the nations promised never to resort to war as an instrument of national policy. But as future events would show, the pact, merely a promise with nothing to back it up, ultimately proved to be worthless (as did the League of Nations, which, in the end, was unable to stop the Axis powers from taking the actions that led to world war).

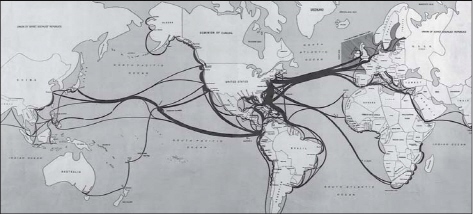

Map 1-1 U.S. foreign trade routes. The thickets of the trading veins extending from the United States will soon be cut off due to the war.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (Travel and Ship under the American Flag, Record Group 178, Maritime Commission)

Sadly, America’s isolationist attitude served only to benefit those nations that made war a part of their expansionist policies. For example, when Japan finally decided to invade a nearly helpless China in 1931, President Herbert Hoover, a Quaker by faith, immediately ruled out military force to stop Japan’s aggression. Instead, he expressed “moral condemnation” and told the world the United States would not recognize any international changes that conflicted with its Open Door policy or the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Faced with moral censure but little else, Japan’s militarists continued their vicious assault against China, which included the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and, a year later, a shocking bombing attack on Shanghai, one of China’s most important trade centers, which killed thousands of civilians.

Similar problems soon occurred in Europe and Africa. In 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia in Mussolini’s quest for a contemporary Roman Empire. The League of Nations tried to quell the aggression with economic sanctions, but they did little good. Mussolini, like his counterparts in Japan, assumed that no one would try to stop his bully tactics, and he was right.

The Japanese pulled out of Shanghai in May 1932 following a truce brokered by the Western powers, most of which had important holdings in the area. However, the Japanese maintained control of Manchuria (which they renamed Manchukuo).

Germany also began stretching its militaristic wings in 1935, when, in direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles, it began to create its powerful air force, the Luftwaffe, and a new navy. The following year, German troops occupied the Rhineland, which had been designated a demilitarized zone. This, too, was in direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles. As with Italy and Japan, however, no one—least of all the United States, which continued to be bound by its isolationist attitudes—did anything to halt Germany’s increasing aggression.